|

Madre and desmadre

I very recently became aware of a Spanish word desmadre, first spoken more generally in my presence and then directly to me by a group of magnificent women in the centre of San Diego. I was told desmadre means ruckus. The way I heard them use the word, it sounded like John Lewis’s “good trouble.” I thought it was two words. Of mothers? No, no, I was told, one word, meaning ruckus. The word intrigued me. Does it have something to do with madre? Well, of course it has something to do with madre, I found. It comes from a root of separation from the mother. Disintegration. Chaos. And now good trouble. In my three works of fiction, all the main characters are women: two wandering mothers, one grandmother, many daughters. My first and third work are about separation from the mother, in one case chosen by the mother, in the other not chosen by the mother. I wanted to close these books, close the stories, go from heimlich to unheimlich to heimlich -- the formula for a good novel I was glibly instructed by a literary agent with unliterary tastes — but the characters are broken are broken, whole only in the luminescence of the world in which they live, loved and loving. Earlier this year I presented the artwork edition of my first novel, Night Heron, in Berlin. My daughter introduced me, moderated the presentation and asked me how I came to write this novel about a visual artist who leaves her son for no very good reason, neither heroic ambition nor poor traumatic past. For the first time in all my stumbling, convoluted speaking about this novel, I spoke about the motivating ambition for this story. It was simple and too ambitiously silly to be spoken of before this, but there in Berlin, speaking to my daughter and a group of mostly artists and writers, I said I wanted to create a female Stephen Dedalus, as in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which I had loved as a young woman. I wanted a woman to step out as vividly: the language, yes, but also that stepping out. I found no Dedalus. There was no easy Dedalus, no female derivative who felt remotely real or interesting. My own life at the time — a mother of young children — pushed me to the not-Dedalus figure of a mother of a young son, and then she leaves her son, which is experienced as desmadre by all readers, disturbingly and uncomfortably so for most, satisfyingly provocative in a melancholy way for some. Art and writing has often propelled or reflected desmadre, traditionally in most parts of the world in the voices and through the agonies of men, often men with, or aligned with, more power (though they could and often did write about men of less power and even women). In the last couple of centuries that has changed. This change has become more rapid in the last sixty years or so as women and traditionally less powerful men — less powerful at least in the context of our long modern era of military gunpowder, industrialization, colonization, and rampant capitalism — have explored what it means to articulate main characters from their own experience of work and living in crowded interior and exterior worlds. Which brings me to an early stimulus for this blog post. A few days ago, biographyof.red, an extraordinarily delightful Instagram account that evidently springs from Anne Carson’s work and posts mostly poetry, posted an excerpt from Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. The excerpt, in turn, quotes Henri Bachelin on the conjuring of myth - involving “tragic cataclysms” of the past, and ends of times — around winter hearths. Evidently this conjuring comes from men, most definitely not old women who tell “fairytales.” Bachelard’s and Bachelin’s lovely words inscribe the space in which old masculinist myths can loom. Their words projected to me a willfully blind desire for understanding that penetrates “the end,” that grandly foresees its own tragic failure. I refused this space and asked myself, what larger space do I make, what poetics if life is the hurling of oneself — whether slowly, grandly, or awkwardly — against the hard transparency of end? What poetics, what space for people living splintered lives — loving, working, laughing, living — and expiring despite themselves, where narratives of yawning pasts and distant ends are often unheeded? Yes, yes, I know, Shakespeare, Dickens, the novel. And, yes, how does this relate to madre and desmadre, apart from the obvious gender stuff. Well, yes, the obvious gender stuff is key. Madre, a trope for connection, with all its connotation of home, gathering, shared food, shared corporeality, cooking, fire, transformation, sometimes even hearth. Complaints, shush, small tales, snoring, reaching into “forces and signs” by women and men. Desmadre, inside and outside. Inside and outside bodies, inside and outside that gathering at the hearth, inside and outside the home, heimlich always roughly pixilated, parts spinning into unheimlich, unheimlich pressed into new forms of homeliness by personal and collective intimacies. From trope to subject, madre to desmadre, women and the historically less powerful are saying we will occupy this hearth, we will make the space under crossing highways a hearth, we will make it a space for life, for gathering, for drought-resistant plants, for art that exclaims “we are here!”, and here encompasses the beauty and pain of our pasts, the struggles and dancing of our present, and our shared future of children, life, and death, all of that! I didn’t know how this blog post would spin out. It is still spinning within, tilting into aliveness, spilling into uncertainty. Madre and desmadre are mythical figures of worlds that have long been binary-gendered. As binary gender dissolves into two figures in a much larger flow, or if gestation becomes incubation in genderless machinery and separation becomes connection to a human, will madre — traditionally female, one of a binary, bloody and corporeal — change? I don’t know. The best I can do for now is to observe that the binary was always only a device, a tool for organizing rhetoric and meaning. The non-binary has always been available, residing in both vast madre and desmadre. Reflecting on the mothers in my fiction and the space-making event alluded to above, madre also seems to connote separation and desmadre also connotes connection, gathering.

0 Comments

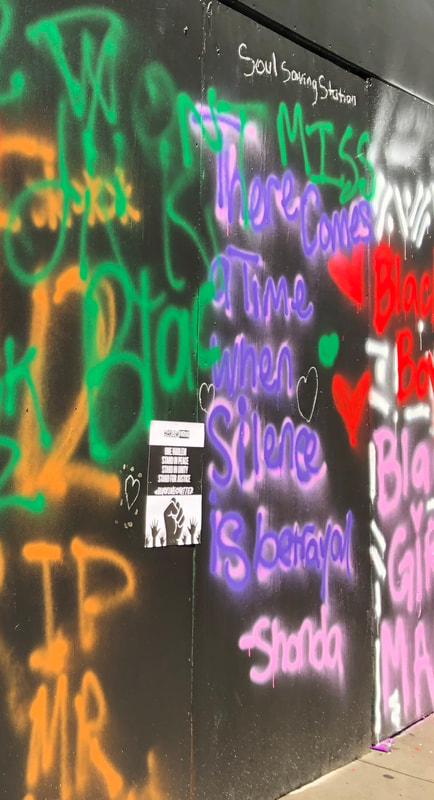

This photograph is of 12th Avenue, not far from my home. This is the route I would commonly use to go down to the River Hudson which I’ve grown to love, and to Fairway Supermarket where I regularly shopped and which has now closed. A couple of months ago I posted this photograph on Instagram with the message that this is also the NYC I love. All the writing and talking about grief over the last months – in the close circle of my personal life and also in wider circles of the published world – led me a couple of days ago to write, in two columns, all the things that have weighed heavy on me in recent times and then all the people who, during these same times, have received love and given love to me in interactions that range from the ordinary and funny to the profound and otherworldly. Over the last week I’ve fluctuated between lows and highs especially noticeably, to the degree I mentioned it in a work meeting as my check-in, noting that I was at that time on an upswing, perhaps even cresting, but knew from experience it wasn’t going to last so I was just taking it as it comes, enjoying it while I could.

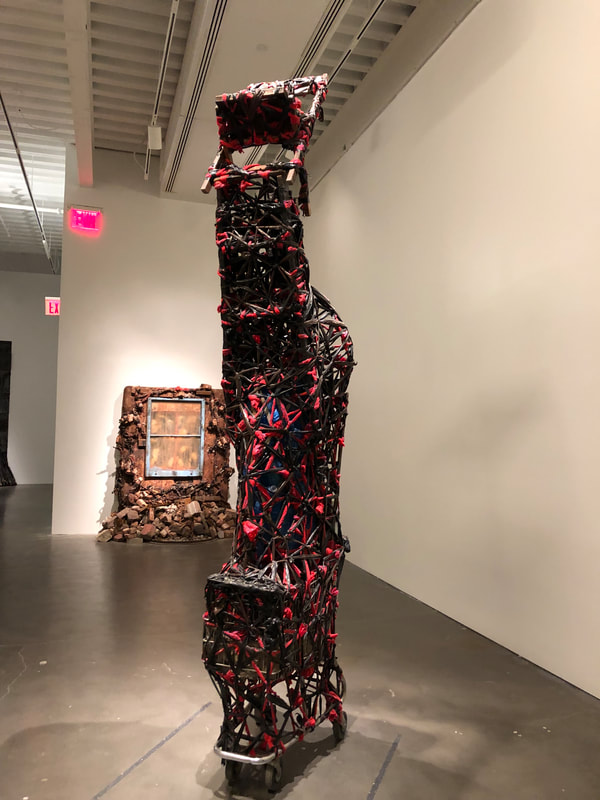

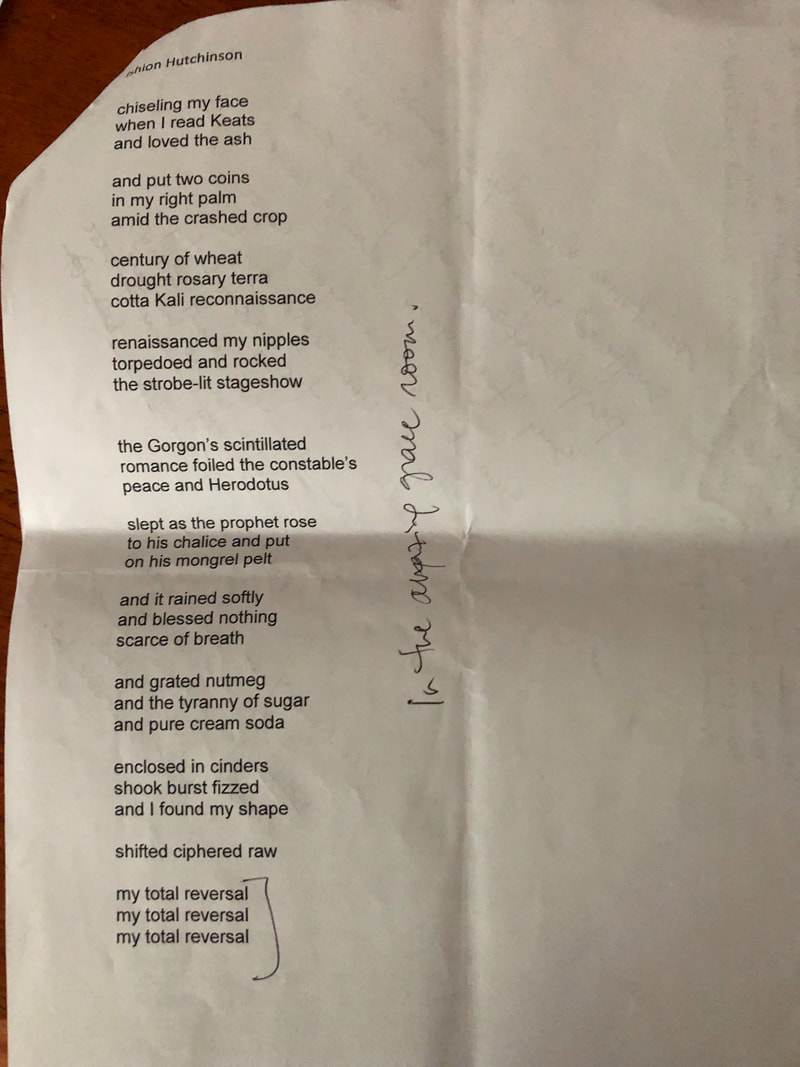

Then Simone Weil’s Waiting for God fell into my hands via a recommendation from Susan Sontag from 1963 and an order from my neighborhood bookstore, Sister’s Uptown Bookstore in the borderlands – actually all one world! – between West Harlem and Washington Heights. I already had Radical Dharma: Talking Race, Love, and Liberation by Rev. angel Kyodo williams, Lama Rod Owens, with Jasmine Syedullah, which came via a recommendation from thandiwe Watts-Jones a few months ago and from Sister’s Uptown also. It quickly became obvious that I had to read these books in tandem, which I am still doing. A few passages stood out early on. Deeply striking passages have become a regular flow now. If I wrote them all I’d basically be telling you to read the books. I’ll just mention a couple of passages from early on that – along with conversations with dear friends, music, and just living in NYC through day and night with intense attention to every phenomenon in these COVID times – stimulated new clarity about what I am calling grief in a general way. If still persevering in our love, we fall to the point where the soul cannot keep back the cry ‘my God why hast thou forsaken me?’ if we remain at this point without ceasing to love, we end by touching something that is not affliction, not joy, something that is the central essence, necessary and pure, something not of the senses, common to joy and sorrow: the very love of God. … There is a God. There is no God. Where is the problem? I am quite sure that there is a God in the sense that I am sure my love is no illusion. I am quite sure there is no God, in the sense that I am sure there is nothing which resembles what I can conceive when I say that word. -- Simone Weil And To embody the truth is to live beyond the limits of self-reinforcing habits, which take the narrative of the past, projected into the future, and obscure the present, leaving us to sleep-walk in the dreamscape of other people’s desires and determinations. It is to transcend the borders directed by pain, fear, and apathy, to discover new territory unbound by the privileges and preferences that trade freedom for familiarity and comfort but pretend they’re one and the same. -- Rev. angel Kyodo williams With all this gathering like water in a wave, though I no longer really know what’s up or down in the making of such a wave, I woke up at three in the morning a couple of nights ago and didn’t fall back asleep for hours. I don’t often have insomnia but I’ve learned that, when I do, it’s best to “play possum,” which is to stay awake, lying still and physically resting, while thoughts and feelings move in and out. The first hour was the usual lying quietly with my thoughts and feelings. Over the next couple of hours I wrote some thoughts, not in one go; I jumped up every ten minutes or so to write an additional thought. I wrote in the dark because I didn’t want my eyes to get dazzled by the page. I did not want my resting body and sort-of floating mind to get dazzled into full awakeness. Awakeness is usually invoked as a very positive metaphor but dazzled awakeness is also restrictive. Here is what I wrote in the dark, really in the dark, only streetlight on the page of my notebook. There’s been grief all my life. Most of my life I lived in the midst of it, not always conscious of it, but in the midst of it. Sometime in the last two decades, while living a suburban working-parent life in San Diego, I separated from grief. My divorce and now our COVID times reconnected me with it. At first it felt like grief spouted singularly from the breaking of my marriage and family, but COVID has pushed me into awareness of all the grief, or at least has put me back into the midst of grief. My separation from grief in San Diego was not because of any special badness in San Diego or myself, but came from a convergence of personal, historical, and cultural time within me. What I needed in my last years in San Diego was not more aware and active efforts to find happiness and experience contentment, as I felt pressured to do by the wider culture, but to feel again the grief that was always there. Yesterday (catalyzed by the writings of Simone Weil, Rev. angel, Lama Rod, and Jasmine S, along with interactions with a couple of dear, dear friends, and my witness of increasing homelessness in the streets of New York), I reintegrated grief as a regular – mutable but constant – part of my life. In a funny way, that reintegration makes joy more possible. My hurt, loss, and grief from the ending of my marriage are real and still present, but the reintegrated grief is something much longer and larger, with many, many sources, ineffable. The grief of my immediate family and childhood friends, the grief in the streets when I was growing up in India, my failures, the grief that surrounds me now, the grief of real people in real pain across the US and world, not just those tragedies out there while I live in my bubble of clutched and privilege-guilt wellbeing here, the grief of family and friends in this latter stage of my life.* (Now back to my writing in the present of this day.) I don’t own the griefs of other people, but I’m in the midst of them along with my own personal griefs. Grief is not separate from me at any time, not even when I feel really happy being irritated with one of my children (or my mother!) or laughing with a friend. I want you to know this. This is not being sorry for myself, or for others. This grief is not instrumental, it is not a problem to be solved, though some of the conditions that give rise to some of the specific sources of grief are problems to be solved. My awareness of the world – joy and suffering – and my commitment to social justice never went away, but I unwittingly separated from grief as part of my life. It became an emotion to get over or a problem to solve rather than an intrinsic part of being. No longer. I can’t ignore it but I can’t control it either. I’m more attuned to, and gentle with, my own and others’ grief, rather than making joy a treasure around which I have to build barriers and defensive strategies, or which I have to pursue blindly. I’d like to stay this way. If you know me, you know that I can be rather joyful, and seek joy for myself and others. That will continue. So will grief. This piece is very personal, but it’s part of work and writing for what I value in life – beauty, equity, justice, complexity, love, life itself. * Some of you may read this as referring to specific grand griefs of specific people. Sometimes grief is terribly grand; often enough, in my understanding, it is not. For many people, let’s even say all, there is pain, sometimes inherited over generations, that’s muted, not even called grief. We all have affliction, grief. Note: The title of this blog piece is exactly the same as, taken directly from, a book by Alice Walker. I have not yet read that particular book, so this blog piece does not refer to its content directly. I have read other work by Alice Walker. The story of how Alice Walker’s title-phrase came to me is in the blog piece below. As the contours of this blog piece have emerged over the last two weeks, it became increasingly clear that this was the right title for it. On May 22, a little less than three weeks ago, my eye was caught by the tagline of an op-ed article in the NYT:* “Better to love your country with a broken heart than to love it blind.” The title of the article was Germany’s Lessons for China and America. The tag line was drawn from something the current President of Germany, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, said in relation to the 75th anniversary of the end of WWII in Europe: “Germany’s past is a fractured past — with responsibility for the murdering of millions and the suffering of millions. That breaks our hearts to this day. And that is why I say that this country can only be loved with a broken heart.” I have seen this phenomenon of loving, or struggling to love, with a broken heart in myself and in others, in relation to people in our lives and in relation to the communities and countries we call “mine” and which have shaped us. People who live in dominant majority communities, as I did growing up Hindu in India, sometimes take a while to feel and understand this phenomenon of broken heart in relation to one’s larger community/country. It took me layers of learning, layers of foolishness, over decades. In 1980, I came to college in the United States, like most people having had some personal challenges (practical, emotional, existential) but generally comfortable in my external identity of (majority) Hindu, well-educated (class-privileged), Indian (heterosexual) woman. Yes, I was vocally feminist and spoke up against injustice as I saw it, but in both cases I felt largely secure in who I was, and surrounded and supported, sometimes prodded, by feminist/left-leaning forebears and peers. My first somewhat conscious encounter with what I might now call loving one’s larger community with a broken heart I remember with shame. I asked another student at my college who was Jewish Iranian whether she felt more Jewish or more Iranian. It was a genuine question and I was struck (silent!) by how much it seemed to hurt her. I did see and hear how deeply that question evoked a negative reaction. It both seemed to miss the point and deeply hurt her. I didn’t know myself well enough to know how to seek further understanding. I never got to know her well enough to come to an interactive understanding of myself and her through the foolishness of that question, and so this retrospective understanding on my part is still partial. Her understanding may or may not coincide with mine. Fast forward to the mid-nineties. I was waiting for my older daughter’s pre-school day to close, just sitting in some random outside space when I was joined by some random man. We started chatting. It turned out he was Jewish and had grown up in Russia. I don’t remember the details of the conversation. He was an erudite and eloquent man and we spoke about Russian literature and music. He knew a lot more than me, which I always love. I don’t remember any details. What I do remember is how deeply he loved Russian literature and music and how much he hated Russia. When I read Roger Cohen’s May 22 piece, I recognized what Steinmeier said. I’m not sure all Germans consciously feel what he expressed, but the question of how you love your country and by extension yourself is a live one for all Germans since WWII, I believe. It took the Holocaust and WWII to make that majority community contend with its own broken heart, to feel the violence embedded in who it is, to see that violence, to face the emotional violence that it has generated and potentially generates, and to struggle with how to love and to love itself with that broken heart. I use the collective “majority community” and the impersonal “it,” but this plays out in individual people, individual hearts, each in its own way. Usually when emotional violence is committed – often enough but not always accompanied by physical violence – the bulk of the resulting emotional work is left to those who suffered and survived the violence, with such effects extending to their loved ones, their descendants, and their communities. The experience of emotional violence and its effects are most obvious in, and to, those who are on the receiving end of such violence, but it also affects, profoundly, the soul and integrity of everyone in that system, whether direct perpetrators, witnesses, bystanders, or those who turn away, dissociate themselves. Fast forward again to about two weeks ago. Angry, heartbroken, and feeling helpless after the video of Amy Cooper in Central Park and with news breaking on the killing of George Floyd by a police officer openly in the presence of other police officers and ordinary people – neither of these new or unusual events – I was conversing with a writer friend, thandiwe Watts-Jones. I spoke about my own anger and heartbreak. I mentioned the Roger Cohen article and the Steinmeier quotation, focusing on the phase “this country can only be loved with a broken heart,” and she pointed out that Alice Walker had written, “the way forward is with a broken heart.” Of course. Today, I am a citizen of the United States of America. I have lived in this country for forty years, about two-thirds of my life. I have been a citizen for a little over fifteen years. I love this country and I am deeply critical about many things here: many of our policies, our current President, the stark structural inequities of our society and economy; and our resistance to facing the physical and emotional violence, particularly to Native Americans and African Americans, that is centrally part of our heritage. I love the music and artistic work of Americans.** I love the brashness of American culture. I love the way Americans come from all over the world, as a result of which we live with immense complexity. I am proud of the stated Constitutional commitment to “freedom, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all.” I became a citizen when I realized that while I am very opinionated politically, I had never voted in any country. I left India before I started voting, and then for more than two decades lived in the United States as a “legal alien.” What this meant was I referred to “you Indians” when I criticized something in India, and “you Americans” when I criticized something in the US. One of the central reasons I became a citizen was to hold myself politically accountable. I didn’t vote for Donald Trump, but I am accountable for the government of the United States. From that sense of political accountability I have grown to know that, as an American, as a citizen of the United States, I also hold accountability for the history of the United States, for what it means to be American, including the hegemonic intonation of “American,” and including the emotional and physical violence of my heritage as an American. What I am as an American today, even being a relatively recent immigrant of color, is also founded on dispossession of Native Americans and the continuous weave of slavery, racism, and anti-Blackness in our history. For several centuries until right now in 2020, we Americans have allowed African-Americans to carry disproportionately the risk of death and other physical violence as well as most of the emotional burden of slavery, racism, and anti-Blackness in our culture. Some form of color- and race-related anger and heartbreak is chronically part of African-American lives. African-American writers and speakers have told us this repeatedly. They’ve told us how their children are taught to watch out for and avoid the risk of being killed, and to expect and overcome risk of humiliation, all this only because of their “color” and “race.” And they’ve taught themselves and their children how to love themselves in the face of indignity that is often intended, sometimes unwitting, how to love themselves and this country with a broken heart. One outcome is that African-Americans have done some of the most extraordinary soulwork of any group of people at any time in history.*** The rest of us – not just Americans, the world! -- have drawn on their soulwork, expressed in music, writing, art, and inspirational leadership. Martin Luther King Jr, Audre Lorde, Malcolm X, Zora Neale Hurston, Frederick Douglas, Oprah Winfrey, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Ta-Nehisi Coates, bell hooks, J. Saunders Redding, Alice Walker, Langston Hughes, Rita Dove, Ishion Hutchinson, Jesmyn Ward, Kendrick Lamar, Nina Simone, Gil Scott Heron, Shirley Horn, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Abbey Lincoln, Jimi Hendrix, Janelle Monae, John Legend, Meshell Ndegeocello, Kamasi Washington, Regina Carter, Noname, Chance the Rapper, Tierra Whack, William H. Johnson, Betye Saar, Romare Bearden, Bisa Butler, Nari Ward, Ja’Tovia Gary, Spike Lee, Simone Leigh, Jeremy O. Harris, Lupita Nyong’o. I could go on. I know some of the work of every one of these people. These are just a few of the African-Americans whose work I have experienced as immensely generous to me and to the world. This brief video made by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre illustrates what I am trying to tell you in this paragraph better than anything I can say.**** Last Christmas, I gave my two daughters Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider, in part because they might learn something about being American and being feminist, but mostly because Audre Lorde is a profound guide in soulwork for anyone, anywhere. When I read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, I suggested that any man should read that with his son. It’s a hard book if you are “white” and live the “American Dream,” but if you get past your defensiveness you will see it is also about engaging with the complexity of the world, about heartbreak, about loving and nurturing and protecting your child in the face of complexity and heartbreak. If you feel into your defensiveness, you will learn a LOT about anti-Blackness in the United States. In ordinary ways many of you – across the world! – draw on the African-American lyrics and music of spirituals, blues, jazz, soul, and rap to engage and understand your own heartbreaks. African-Americans have done the bulk of the emotional work of our country for too long. Over the last few weeks, as our country increasingly convulsed with pain and protest, the rest of us are beginning to pick up our share of the emotional work, our share of the effects of the emotional violence of racism and anti-Blackness. This isn’t just about empathy from the outside – often forms of what Dr. Kenneth Hardy calls “privempathy” – but eventually about learning to feel that wherever you are in a system that breaks someone’s heart, tending to their heartbreak means recognizing your own broken heart, the irrevocable break in who you are, and learning to love, and protest (and make policy changes! and change our culture in fundamental ways!) with that broken heart. [ADDED NOTE: I was corrected by a reader: “privempathy” as referred to above is not merely empathy from the outside but is the “hijacking” of the experience of an African-American by empathizing through one’s own (privileged) experience of some form of hurt/subjugation. The notion of “privempathy” is described in this summary of Dr. Kenneth Hardy’s very compelling, and challenging, approach to cross-racial work. In some ways, the generalization of broken heart work in this paragraph may be interpreted as a kind of privempathy. Please see the end of this blog piece for a longer/larger clarification of what I mean as I call for this 'broken heart' work around anti-Black racism in our country.] Broken heart is a beginning. For Zen and Leonard Cohen fans, it’s the crack that lets in the light. A week or so ago, I wrote to a colleague, someone I don’t know well, about my (and shared) anger and heartbreak. I added an apology in case he felt I was overstepping into the personal. He wrote back that “reaching out with a loving heart is never overstepping.” When I recounted this exchange to another colleague and dear, dear friend, he commented that this exchange illustrated stepping into being vulnerable with a broken heart and open with a loving heart. This isn’t easy and often I feel foolish, and sometimes I’m told I’m foolish, or even downright wrong, directly or indirectly. If you have read thus far, some of you are probably saying, yeah, yeah, but what do we DO?!! I do believe that soulwork is essential, but as Audre Lorde said to her African-American sisters: “And political work will not save our souls, no matter how correct and necessary that work is. Yet it is true that without political work we cannot hope to survive long enough to effect any change.” She made that call to her sisters in the early eighties. Now in 2020, I say to my fellow Americans who are not African-American, while political work will not save our souls as Americans, extensive political work is needed to keep African-Americans alive and have equal access to good health and opportunity for “the pursuit of happiness.” Even today, June 10, 2020, African-Americans routinely face systemic inequity in education and healthcare, and discrimination in work places and public areas. They face very significantly disproportionate risk of death and indignity at the hands of police as well as non-police community members, and historically such acts of physical and emotional violence have tended to go unpunished or minimally chastised. The protests after the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, which followed the stark demonstration of structural inequality in COVID19-stricken New York, suggest that we may have come to a major turning point. Some of my thoughts on what is to be DONE are below, but first a note addressed to immigrants of color like me. This blog piece is written for all non-African-American citizens of the United States, but here are a few words for immigrants like me who are not white. While we may have our own experiences with racism and colorism both within and among us, and as we engage with fellow Americans, we also own the history of anti-Blackness and racism towards African-Americans. That racism and anti-Blackness is deeply our heritage as Americans. As my niece Mallika Roy taught me, we can’t just assimilate to some form of “white privilege,” or appropriate the African-American experience of racism as our own, or just sit out of this enormous political, cultural, social, and economic question that dates back to the earliest years of our country. To get us started, here is a great letter written by Asian American children to their parents four years ago, in 2016. So, now, some thoughts on what is to be done: -- Speak up -- VOTE!

-- Support activism and campaigns to change policies, government apparatus, and political leadership to

-- Pay attention to inclusion and exclusion, both implicit and explicit, in your workplaces and communities.

-- Do soulwork to understand better what African-Americans have suffered, learned, and given to the world; and to examine your role (you, yourself, as well as the you that lives out of complex and long-developing heritages). Carry some of the burden of the emotional work related to the physical and emotional violence of racism and anti-Blackness that African-Americans have carried for generations.

-- Don’t run away. It’s hard to live with what you can’t solve and with the pain of inequality, the pain of your own privilege and someone else’s suffering, to live with a seeping guilt (avoid that!) of your heritage(s). But, really, don’t run away! -- In the end, be guided by the excellent three steps offered by Maria Ressa, a journalist from the Philippines, in the graduation speech she gave in May 2020.

Acknowledgements: If you know me you have probably shaped what I’ve written here and/or heard some versions of this. If you see yourself in this piece, you probably are in it, even if I haven’t named you explicitly. That said, I started on this path most consciously in San Diego where there are particular people who have guided and pushed me in extraordinary ways. These include: friends and colleagues among the organizers, faculty and fellows of RISE San Diego’s Urban Leadership Fellows Program particularly in 2018 when I was on the faculty; staff and members of USD’s group relations conferences, particularly of the On the Matter of Black Lives conference held in March 2017; and finally words aren’t enough to acknowledge the guidance, patience, knowledge, and loving hearts of my dear, dear friends Zachary Gabriel Green and Cheryl Getz, and also Henry Wallace Pugh who has stood beside Cheryl for as long as I’ve known her. Of course, that doesn’t mean they would endorse what I have written here. These are people I have grown to love, which is the full face of gratitude, but I am still learning, still making mistakes, still working through my own cluelessness. _____ * The NYT is still figuring out what it wants to be in the 21st Century, as we fell into a Trumpian age that I hope we are clambering out of now. The NYT is not alone in this, but as one of the most prominent news organizations in the world, its spinning across torment, sentimentality, overwrought opinion, (rarely) humble offering of information, portentous screeds, and occasional brilliance affect us all. After all they are not a blog! And yet I read and learn from their articles. In many ways they represent and express a swath of our zeitgeist. ** This is a good time to acknowledge that I use the word American as the most quick and convenient designation for those who seek the benefits of, and carry accountability for, being citizens of the Unites States of America and as an adjective pertaining to their lives, activities, and creations, but I am aware that in the context of US domination in the Americas, “Americans” may intone and express a sense of US hegemony in our hemisphere. *** I learned the word “soulwork” also from thandiwe when she referred to the work – “soulwork” – of the Eikenberg Academy founded and directed by Dr. Kenneth Hardy. The word may have a longer history, but I learnt it from thandiwe and Eikenberg. I receive it as an evocative word for emotional work that goes deeply into what it means to be human, filling out and beyond, with great beauty and expansiveness, the more standard “life of the mind” that tends to get foregrounded in the “Western” (“white” or Euro-American) traditions. **** I haven’t written about influential African-Americans in sports because I don’t watch or follow any sport, and don’t really know enough about any particular person in sports. Note of clarification added June 17, 2020: A question from a friend who read this post led me to write this clarification. There are two pieces to this clarification. First, while it is written for anyone interested in reading some of my (still learning/still developing!) understanding of anti-Black racism in the United States and what needs to be done now, it is addressed primarily to non-African-American citizens of the US. Secondly, and very importantly, African-Americans don’t need to be aware of broken hearts and loving this country with a broken heart. They know this already! Their hearts have been broken over and over and over again for more than three centuries. And yet in 1955, James Baldwin wrote in Notes of a Native Son, “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Then in 1984 he had the following exchange with an interviewer for The Paris Review. INTERVIEWER “Essentially, America has not changed that much,” you told the New York Times when Just Above My Head was being published. Have you? BALDWIN In some ways I’ve changed precisely because America has not. I’ve been forced to change in some ways. I had a certain expectation for my country years ago, which I know I don’t have now. INTERVIEWER Yes, before 1968, you said, “I love America.” BALDWIN Long before then. I still do, though that feeling has changed in the face of it. I think that it is a spiritual disaster to pretend that one doesn’t love one’s country. You may disapprove of it, you may be forced to leave it, you may live your whole life as a battle, yet I don’t think you can escape it. These thoughts and sentiments have been expressed in word and action by many, many other African-Americans. So, no, African-Americans don’t need to be aware of broken hearts and loving this country with a broken heart. They know this already. It’s the rest of us (not Native Americans, who suffered violence and dispossession in the founding of this country, and who like African Americans have carried the burden of that emotional and physical violence) who might want to consider how we, as Americans, are broken. That, yes, we aspire to “land of the free,” AND that that aspiration also is based on a history of cruel dispossession and violence. This is not work for African-Americans to do nor do they need or want to help us do this work. This is our work, the rest of us, most of all white/Euro-Americans, but the rest of us as well. What African-Americans do need and want is for us to make our American culture and institutions less life-threatening and blocking to them. This is not about being sorry for African-Americans; they do not want or need us to be sorry for them. A couple of days ago, Imani Perry wrote a powerful and beautiful article in The Atlantic on this. Do read it. So then, what do we do with being aware of our brokenness as Americans? I don’t know. We’ll live some answers and then modify them as we see the effects of those answers. I think if we are more consciously aware of our brokenness – which cannot be erased, which is a core part of our history as citizens of the United States – we will shift our culture and institutions from the systemic injustices that arose from our violent history and we will love ourselves and others more fully. If you doubt love has anything to do with this, here’s something that James Baldwin wrote: “Love does not begin and end the way we seem to think it does. Love is a battle, love is a war; love is a growing up.” —from Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son (1961) Read James Baldwin, if you haven’t already. Every time I read James Baldwin I learn something about myself and the world. The focus on emotional and physical violence against African-Americans does not mean that other forms of discrimination, exploitation, and injustice don’t exist, or that economic systems don’t exacerbate climate change with all the effects it will have on vulnerable populations and ecosystems worldwide. I believe, though, that not only is eliminating the gross perniciousness of anti-Black violence way overdue, these various areas of systemic dysfunction are connected, and anti-Blackness is both a foundational element and one of the most terrible manifestations of linked injustices that have built up worldwide over centuries. I believe the building of concerted awareness and action against systemic anti-Blackness will vitalize other critical movements for change. (Spoiler alert re the movie Pasolini) The sequence of Nari Ward, Ishion Hutchinson, and Pasolini just happened; there was no plan on my part. Nari Ward and Ishion Hutchinson were paired by the New Museum. Not unexpectedly, they were a good pair, or rather I found Hutchinson’s response to Ward’s art provided something like a blended glass, part mirror, part filter. More about that in a bit. I added Pasolini because I wanted to use my Metrograph membership; I could walk to The Metrograph from The New Museum, and Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini was playing at the right time for me to move in this way through the city. Interestingly, going to Pasolini also became the right movement for a kind of intellectual and emotional trajectory. Though this is often the case as we knit the past into some kind of coherence, in this case I struggled with making the sequence coherent, then forced a coherence, and then was struck by what came of and from the forced coherence. I went to The New Museum for the first time about two weeks ago because a friend wanted to go there and I’ve wanted to go there for a long time. We started on the top floor with Jeffrey Gibson’s kaleidoscopic work and I passed through his work, loving the color and the immanence of movement. Later, I passed through Hélène Cixous’ odd, insightful, and romantic essay on Gibson’s work. “A dislocation is at work,” she wrote. Then we went down three floors of Ward’s large installations and smaller, more compact, art in the exhibition called “We the People.” The making of art from found objects is not new but the poignancy of this exhibition lay in the bend between the mourning of pain and history, and the fertility and beauty of, somehow, life. I had not heard of Nari Ward before this and got a little uncomfortable when I heard that he is a Harlem-based artist and his art connects directly to dispossession, not only of the past, but directly in the effects of gentrification in the present. I moved into West Harlem in June 2018, an innocuous, older-ing, and brown woman. I belong here, and I don’t. I had noticed, when checking out the museum before I went there with my friend, that Ishion Hutchinson was going to do a gallery talk on Nari Ward’s work. When I asked if there were still tickets available for that gallery talk, I was told there were. I was stunned. I guess this is NYC. I said, if you don’t think they’ll sell out while we, my friend and I, go through the exhibitions, I’ll wait to see Nari Ward’s work before buying a ticket for Hutchinson’s gallery talk. They assured me there would still be places, and there were, and once we’d walked through and down all the floors, I bought a ticket for the talk. So, on Thursday, May 16, my hair freshly colored, I went back to The New Museum, and waited for Ishion Hutchinson’s gallery talk. Ishion Hutchinson, like Nari Ward, is Jamaican-diaspora African-American. He is a poet I much admire. He took us, a group of about fifteen people, through parts of “We the People,” with eloquence, diffidence, clarity, and kindness. He took us – none of us belonging to the African diaspora, though all of us share fraught histories with Nari Ward and him – through touching what ‘fugitive’ can mean in history, selfhood and art; through hearing the grandness of aspiration while living in “material fetishes of failed utopias;” through sensing, distantly – in our case, each of us, perhaps with some guilt, or shame, or desire – “an old resilience which is part of [Hutchinson’s] heritage.” He told us about the abeng, and made its sound with his breath, his throat, and his mouth – this was a generosity of sound, not just a performance or lecture – and related it to the artwork called Savior. The abeng, he told us, makes the sound of the fugitive. He lost his voice briefly after making that sound. He stood in front of the two pieces called Breathing Panel and, at the end of his prose response to the artwork, repeated, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe….” In that brightly-lit gallery, with chattering, whistling sounds from an adjoining artwork, with only one other African-American, a gallery attendant, in view, with one other gallery attendant who looked Latino, and me, a class- (and caste-) privileged South Asian-American, with everyone else phenotypically white, mostly women across a range of ages, I wondered who couldn’t breathe now, why couldn’t they breathe. Who is breathing? For how long? Then he took us to the large, dark room in which Amazing Grace was installed; “a womb, a slave ship, an ark,” he called it at the beginning and towards the end. He walked us, two-by-two and holding hands, through the stroller-ship-womb. He read his poem Sprawl and repeated “my total reversal” – the last three lines of the poem – more than three times. And then we were done. And I got him to sign my copy of House of Lords and Commons which he not just signed, but also inscribed with “a small, drifting raft” for me. I walked out into the sunny afternoon, exchanged cheery words with one of the outside guards, walked through Chinatown, got a text message from my daughters in which they laughed at my ‘culture-vulture’ day, got to The Metrograph, and bought a ticket to see Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini. On Instagram, I posted some pictures and wrote: it’s hard to call walking through Nari Ward’s work at The New Museum a pleasure, but perhaps one can call it a tenderness, an amazement at how beauty can come alongside, and from, ugliness and sorrow while underlying cruelty and pain remain cruelty and pain. Pasolini starts, if not right away then very early on, with explicit, aggressive, unlovely sodomizing of two submissive young women. With Pasolini, I seemed far from the fugitive grief and anger and grace of Ward’s work and Hutchinson’s words. There was abject or abjectify-ing sex, followed by ordinary domesticity and interesting, but cold, words. “Narrative art is dead,” Pasolini told us, “we are in mourning.” “Mine is not a tale, it is a parable,” he said, “I am a form, the knowledge of which is an illusion.” To Pasolini, it appears, I, Meenakshi, am a moralist, who neither seizes the right to scandalize nor feels pleasure from being scandalized. About a third through the movie, I wrote in my running notes: so far there is very little that one might call kindness, or love, or tenderness. I watched more sex -- this time apparently not abject or abjectifying, more a kind of revolutionary procreation in a reversal of desire -- between beautiful people, with a raucous audience within the film, and us, a quiet audience outside the film, with our own arousals and withdrawals. Pasolini sees his work as a revolution. “I’m asking you to look around,” he says, “and see the tragedy… … starting with universal education … which leads us to want … and not stop short of murder…. … an appalling tradition that is based on this idea of possessing and destroying.” * The tenderness came at the end of the movie, when Pasolini is beaten to death on an industrial beach and the movie closes with a “clip” from a made-up movie based on Pasolini’s last work-in-progress. In the clip, Epifanio, an older-ing man, and his young companion are trying to get to Paradise and Epifanio can’t go on, so the young man says, “The end doesn’t exist. So we just wait. Something will happen.” Obvious shades of Godot, but owned here in its own terms, with its own peculiar pathos. In the end, the tenderness comes from the unabashed living of, and looking at, life with all its ugliness, its earthiness, its longings, its sensuousness, its beauty of form and light and shadow, its flaws, and just life. In general, I prefer to look at, sense, and join joy and tenderness of a different kind, but I did feel the tenderness at the end of this movie. Then started the struggle of knitting the coherence of my past. In my head, I stared at the obvious challenges of colonialism, racialism, the cruelty and survival of color lines of history, simplistically pitted against normative sexualization, scandalous desire, the intense ambivalence – intimacy and violence – of sex, and the cruelty and survival of power lines of history and didn’t get far, actually didn’t get anywhere, so retreated to higher abstractions. This is what I found. In Pasolini, there is no redemption, no desire for redemption. There is (only?) a wild grasping for freedom outside a cruel system that must be broken. In Pasolini, to the degree there is redemption, redemption lies in the external viewing of a complex tale – not a parable – about an ambitious fragility, or a fragile ambition. In Ward’s work and in Hutchinson’s words, there is redemption. Pain is overcome – indeed redeemed – by creation, by making beauty and life, and, in flashes, love and joy, from the remains of things, bodies, words, feelings, life itself. In Ward’s and Hutchinson’s work, perpetrators are on the other side; Ward’s and Hutchinson’s focus is on fugitiveness and resilience (Hutchinson’s words). In Pasolini, there is nothing fugitive, no one hides (except, perhaps, one time in the movie when Pasolini evades his interviewer’s question about what would remain if Pasolini could magically wave away everything he opposes), apparently nothing is hidden, perpetration is right there in front of you, drawing you in, people are broken down, perpetration itself is broken down. From this forced coherence, I knitted an easy/uneasy synthesis. In the face of suffering, sometimes one wants to shove perpetration up front and say, “fuck you, I don’t care!” Other times, one holds on to beauty, to the possibility of beauty; you want to cry because you cannot but care. And, zooming out, a creation that expresses only one of these impulses will feel flat – just brutal, or just sentimental. I did not find Ward’s, Hutchinson’s, or Ferrara’s work flat. To close, in my way: when I first decided to write about my forced coherence, I didn’t plan to include Jeffrey Gibson’s art and Hélène Cixous’ writing. But, having written thus far, I want to end with Gibson’s resplendent art. That is also life. And Cixous wrote of his dolls, which did not figure in this current New Museum exhibition, “… these were his people, his heritage, his self-portraits. Beautiful dreams, realized, and guarding their secrets.”

*Note: I wrote these words in my running notes. I’m pretty certain all the words and the logic they convey are accurate, but I’m not so sure about the ellipses. Anna Seghers’ Transit is astoundingly contemporary, though completed in 1942.* In the most practical, palpable ways, the book describes the pillar-to-post, paper-and-more-paper, and rules-petty-power/lessness-and-helplessness of trying to cross a national border when you are wretched. The novel was written in the middle of the 20th century, the nation-state-century, when the science of borders became so fine that it could define in OR out, pure OR impure, and even what morally belonged as opposed to what must be kept out, just by whether you filled in the correct forms correctly, which allowed the gatekeepers to see quickly the lines that ran on one side and on the other side of you. A primary line running right through you did not, does not, bode well.

I entered a mild form of that kind of transit world in the 1980s and early 1990s, as I went to and from the United States as an Indian citizen with a U.S. student visa. Today, as a U.S. citizen of some means, I rarely have to enter that world. In 2018, we still seem to be in a long nation-state-century, though perhaps we’re in a globalized-hyper-transit century. We won’t really know until the evolving science of borders catches up with contemporary phenomena, forms, and technologies. So that’s it for the most obvious point to be made. Transit, the novel, was wholly suited to being made a contemporary film, which it has been. But Transit is not just a novel that has contemporary resonance. It is a story that is both fascinatingly flat and intensely dynamic. It is as if Seghers cut a slice of a whorled, recurrent world – that she calls an “ancient, yet ever new … … present” – and conjures for us all the details – people, forms, places, ships, days, victuals – as they move, connect, break down, reconnect, slip off, and are replaced. The story is narrated by a young man, in my view with the voice of a mature woman (plausibly a mature man, but implausibly a young man). In that period, a woman could not easily have wandered, gazed, and desired, so the narrator is a young man who is a curiously passive and blank character. His main foil, a young woman, another blank character, is hyper-active and always running after. Third in the key triangle of the novel is the explicitly blank character – for all practical purposes a fantasy – of a dead man, a writer, whom the narrator pretends to be and whom the young woman seeks. The story of these three blank characters becomes the web that holds the world of transit in Marseilles at the beginning of World War II. Strung on this web – moving along, sometimes jumping off or jumping back on – are small characters, socially and otherwise varied, who are perfectly alive. Encircling the web are small, and larger, and overlapping, environments – cafés, waterfronts, stairs, rooms with a wall on this side and a wall on that side, a view of the sea beyond “where the road took a turn and the wind was the strongest” – which add up to what Marseilles was at that time, but also, as peopled by the various small characters, to the state of transit as the roiling object of the story. Anna Seghers draws us in with the seductive narrative threads of quest, adventure, impossible love; in a curious inversion of the Orpheus-Eurydice myth, Marie runs after death and finally meets it. At the end, these narrative threads remain thin – almost transparent, almost air – but sustain a busy world of “present,” with all its waiting, living, and small moments of kindness and loving amidst known meanness, desperation, and death. The basic triangle, the detailed representation of place, and the reliance on small, recurrent characters are not unusual.** What is striking about Seghers’ novel is the deftness with which she uses a somnambulistic, Heinrich Böll’s word, narrator to tell a compelling and dynamic story about a slice of time. * It was first published in English and Spanish translations in 1944 when Seghers was in Mexico, and appeared in German in 1948 when Seghers was settled back in East Germany. Seghers’ choice to live in East Germany was controversial. The permanent return of the authorial voice of this novel to East Germany does intrigue me, but maybe only because I have some deceptive clarity of hindsight and distance. ** Reliance in long fiction on a wide variety of small, recurrent characters seems to belong more to places and times where lives are crowded and not as socially segregated as they seem to be for the dominant literary writing classes of the United States. Two weeks ago, a companion called Leah Goodwin taught me and others a mysterious healing process. Mysterious to me, that is, probably not mysterious to its practitioners, whether in Hawaii, its original home, or elsewhere. According to Leah’s teaching, a therapist heard that a healer cured a group of unhappy people, with bewildered minds, without using drugs or psychotherapy. The process has a name that sounds silly to me – ho’oponopono. The therapist, Dr. Ihaleakala Hew Len, tried it out, found it worked, and passed it on, as Leah did.

When Leah talked us through the process, I found myself sandwiched between tenderness and embarrassment. Used correctly, it calls for complete and ridiculous openness. Nobody could, or should, be open like that, not even a child, I thought. But when Leah taught this, I was with a group of people I’ve grown to love and trust. I stood in the shadow of friends who knew I was a fool and somehow found me wise. With them I could be that open, that ridiculous. Ho’oponopono involves the incantation, with conscious and deep intention, of four sentences to oneself, or to another, preferably both (and, if both, that means all). The sentences, Leah told us, could be in any order. She has a preferred order, but any order is fine, so long as all four sentences are understood, spoken, and intended. These sentences sounded moving and profound, even divine, among these friends I trusted and who learned this process with me. Imagined beyond this group, they seemed frightening. They risked giving away too much, I could lose myself. If they were not matched, I could be reduced to a sentimental puddle – abject, without definition – and forever depleted. So what, already, is this incantation?! What are these sentences? I’m sorry. Forgive me. Thank you. I love you. As I quickly typed these sentences, then hurry my eyes away from them to these words here, I think, gosh, if Kavanaugh said these. Of course, I don’t want him to, because that would make him pretty amazing – what were those words I used? moving and profound, even divine – though conservative. His saying these sentences would challenge us on the political left to take “compassionate conservatism” seriously, to consider saying these sentences to conservatives. But, ha, ha, he is far from saying it and, from where I sit, conservatism still looks rather un-compassionate. In case you (meaning I) need reminding, I still don’t like him and I still want to work for change in the 2018 mid-terms. Rationally, truly, ho’oponopono has its limits. Dragging the process beyond these limits can be dangerous. In some ways, best to forget all about it. But I shan’t, because ho’oponopono is not about reducing myself and you and susceptible varieties of bleeding hearts to loving blobs without definition, difference, and conflict. Ho’oponopono is not about side-stepping definition, difference, and conflict. Ho'oponopono is being unafraid to love even where there is definition, difference, and conflict. It is trusting that I will not lose myself if I say I am sorry. It is trusting that gratitude/love/apology/forgiveness and accountability can co-exist. Indeed, gratitude/love/apology/forgiveness offered with the (embarrassingly!!!) open spirit of ho’oponopono, is a true invitation to accountability, to own all of yourself. Where ho’oponopono is most needed is where it is hardest. I can’t yet use it in my hardest places. Better to laugh. Better to scorn Kavanaugh. Best (more sneaky, more virtuous) to ruminate: if I think Kavanaugh should say I’m sorry Forgive me Thank you I love you … what would it mean for me to say to Kavanaugh I’m sorry Forgive me Thank you I love you ? And yet, today, with all the swirling ill-will that continues to surround and emanate from the Kavanaugh nomination, even this virtuous self-examination, this sneaky hypothetical, is walled up and dull. WARNING: If you have not read the book, there are spoilers in this review.

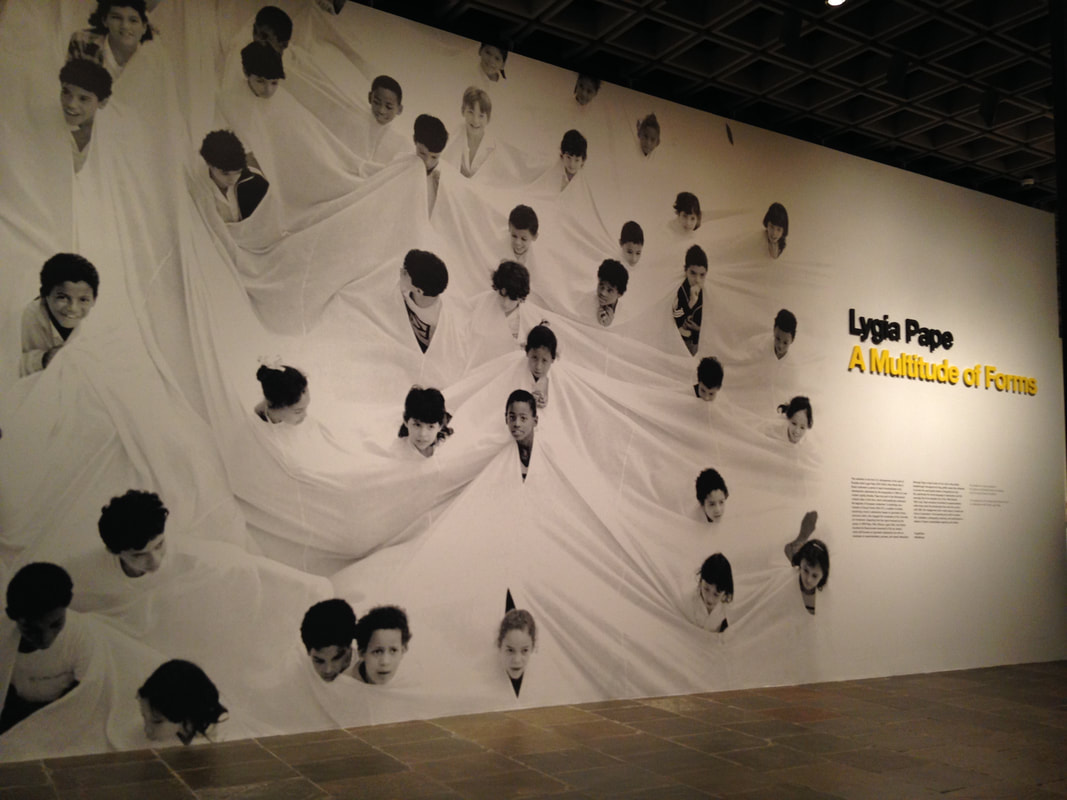

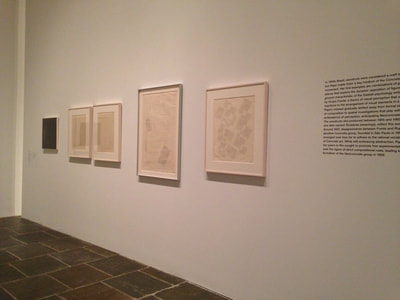

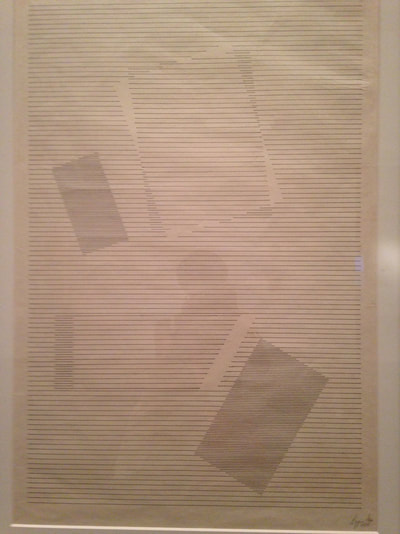

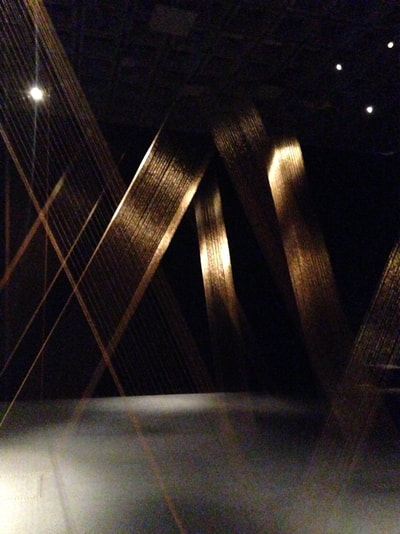

Like many cosmopolitan, post-colonial South Asians, Hari Kunzru writes extraordinarily well. He knows and loves words in the English language, not just the functional language of the British Islands, but the de-territorialized language of twentieth century globalism, kneaded by diaspora intelligentsia, whimsically dipping into the vernaculars and dialects of English-speaking localities, and – in Kunzru’s case – ironically, but also desperately-lovingly, seeking to use English, a language of modern power, as a moral language that mourns, assesses, and stays alive. In White Tears, he writes beautifully and he has a fabulous, intelligent, moving, and unusual concept. As an aside, but this is important, I came to the United States in 1980, a post-colonial Indian, fresh off the boat, not knowing the blues at all.* I’d heard jazz and rock, and, yes, I may have listened to Billie Holiday, but simply as jazz. I did not know the blues. In the early eighties, three young white people from North Carolina introduced me to the blues. A few years later, more white people introduced me to more blues. No African-American has introduced me to the blues, though one here, or one there, may have listened to a song with me. White Tears is about the blues. It is also about incarceration, racism, American government, guilt, and blaxploitation. I read it after J. Saunders Redding’s No Day of Triumph, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, also some Flannery O’Connor, but before Marilynne Robinson. This context is important because it reflects one thread of twenty-first century grappling with “race” in the United States: immigrants, especially non-white immigrants, consciously – intellectually and morally – adopting and owning the race history, and the racial present, of their new country, trying to find to find an American identity between, or beyond, the two easiest choices: “to assimilate into White culture or to appropriate Black culture.” ** The main characters of White Tears are two young white men and a vengeful black ghost. The two white men love music, particularly the blues, particularly the richer white man. The poorer man is adept with technology, the richer is a collector, and neither is good at navigating the moral delusions of human societies. Kunzru sets up a gorgeous plot device which begins with Seth’s hearing a song fragment while randomly recording street and other public sounds in New York City. It leads to a theft of intellectual property, of cultural property. We don’t know it, but the past is vengefully inserting itself into the present. We get a hint of mixed realities but the language of reality keeps us grounded in the present. The rich boy, Carter, gets beaten up and disappears into a coma, but we are not sure if all of that is real or a delusion. The remaining boy (Seth) knows that the attack on Carter has something to do with the theft of the song, but he believes that the threat will be dispelled if he can explain and prove the innocence of the prank. Meanwhile, he has geeky hots for Carter’s rich sister (Leonie), is conned by a journalist masquerading as a friend, and draws Leonie into the retracing of a tragically exploitative trip, during which she is pruriently murdered and he falls into his first full hallucination of white face-black face. From that point, the narrative spirals towards to the climactic integration of evil-innocence-cluelessness-privilege-death and subordination-suffering-incarceration-ghostsofChristmaspast. The problem with White Tears is it is not a tragedy. The bad people are unambiguously bad. Revenge is simple. The innocent are clueless, and cluelessness is not innocence. Kunzru’s story is very powerful, relating a national, indeed global, history of extreme exploitation, of capitalist and racist privilege, of systematic cruelty. This is a story of deep red and black strokes. The flaw in White Tears is that he tells it with deep red and black strokes, but he – diaspora brown, and post-colonial like me – does not have adequate color capacity for it. Coates tells it black and red, unrestrained, and sometimes tenderly, from his heart; he himself grows in the telling. Redding’s 1942 travel memoir is written with a post-War, pre-Civil Rights optimism. His telling is fluent and dispassionate, skillfully weaving literary English and the vernaculars of the southern localities he visited. With scholarly calm, Redding chronicles harsh and casual racism, and the human frailty of Southern Negroes (as they were called in the forties), whether beaten down by poverty and racism or, if well-off, struggling to reconcile racism and economic privilege. Americanah’s narrative goes from the ordinary color consciousness in a non-white, post-colonial, independent state – in this case Nigeria – to consciousness of racism in the United States, with a side journey into racism in England, and back to a twenty-first century globalized consciousness of race and color. Like Kunzru, Adichie writes with all of the skill and confidence of the educated post-colonial cosmopolitan. She claims all of the English language, and writing phenomenally, so to speak, claims all of the colors her novel can bear. She cheerfully presents us with types, and then just as exuberantly adds their ingrown hairs and pretensions. In the end, Coates, Redding, and Adichie write about flawed people loving, exploiting, or being clueless about flawed people. Held against them, albeit serendipitously, Kunzru writes about bad, or consciously false, people exploiting weak people. In White Tears, Hari Kunzru writes a superbly ambitious story. He manipulates structure, language, and plot both intriguingly and smoothly, and his characters are often perceptively drawn, although sometimes with more self-conscious irony than needed. However, in this brave effort to write about race in the United States without (simple) assimilation or (strident) appropriation, Kunzru loses his voice, and as a result no character is full, not as black, not as white, not as female, and not even as male (or other gender). The characters who are closest to being full are the two lonely older (white) men, JumpJim and Chester Bly who move through their ghostly parts in ways that are both lumpy and alive. They are not stock characters dressed up; they have shadows that allow me imagine into them. JumpJim shuffles and obfuscates in palpable ways while Chester Bly travels through the south like a lovingly-rapacious white doppelgänger of J. Saunders Redding. To the degree this review sounds critical, it is not about throwing shade on Kunzru for misappropriation nor is it calling on Kunzru to add a “brown” voice if writing about race in the United States. Rather it is a rumination on the difficulty of trying to write about race in the United States, where every word takes a stand and every word can be hurtful. One path to safety is to write what, at its fullest, is an uncontrolled narrative in a highly controlled way, where the writer is apart and in control always. The rub is that ‘to be in control always’ can only be achieved with a limited range of representations. This means that the writer risks being more on the mechanical end and less on the “live” – internally conscious, escaping, haphazard – end of narrative representation. As a South Asian diaspora voice, Kunzru writes very carefully about race in the United States. He is not afraid to personify the badness of racist capitalism and the will to vengeance of the historically exploited. But, in a curiously ironic way, while he makes the blues the heart of the story, he loses the pathos of the blues which is a human pathos. The whiteface-blackface-whiteface torment in Seth’s story comes the closest to pathos, but Seth loses palpability as his delusions are cleverly articulated. In the end, his delusions and hallucinations come across more as elaborately didactic representations of the delusions and hallucinations of racist capitalism than as human pathos that wends through will to/subordination to power, desire, suffering, love, weakness, and death, though not necessarily in that order. * For more on my slow, always incomplete, learning about race in the United States, see my blog post The Color of People. ** Mallika Roy, Hardly Un-American In the past it appeared that the engagement intention of art was to conjure a single bond, however illusory, between the viewer and art object before her. Supportively, the role of a curator was to present the art object in the best way to achieve that singular moment. Contemporary art, which seems loosely to be art created over my now-rather-lengthy lifetime, appears to have different and broader intentions, or perhaps these intentions have been laid upon it by the accelerated popularizing of art and the bolder actions of curators.* The curator in contemporary art seems to have developed into something between a composer and conductor, who orchestrates a dynamic multi-sense, multi-directional engagement between the art, context, and viewers, and invites the single viewer into a kind of performance which they** can choose to enact somewhat hermetically amidst wraiths, or somewhat chattily among other willing or unwilling members of an expedient ensemble. My most recent experience of contemporary art-watching happened in New York City, with a prelude visit to the Rubin Museum which presented “historical” objects in a winding, resounding, compartmentalized, but also fundamentally open and flexible, space. I went to the Rubin for the Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition and was properly astounded by the intensity of each photograph, each a composition by itself. I left the Rubin struck by the Buddhist iconography and sounds of the museum, which enfolded the more traditional presentation of the Cartier-Bresson photos, and conjoined easily the meditative, the erotic, the powerful, and the immanent. One could have chosen to visit only the Cartier-Bresson exhibition but that would have meant a deliberate shuttering of the senses, or an excision of a limited exhibition space – its photos, air, light, and walls – from a larger composition.*** The visit to the Rubin was a part of seven days of walking, working, eating, talking, thinking, and feeling in the city. The walking (around Williamsburg, the Village, from midtown to the upper west side, loitering, speeding, jostling), working (resisting and learning how to pitch and sell my first novel), eating (patatas bravas, Singaporean street food, Korean fried tofu, street dosas, a street hot dog, cauliflower tacos), talking (about politics, change, love), thinking (about strategy, living, composition), and feeling (the humidity of NYC summer, the grittiness of dust and burnt fossil fuels, the rhythm of slowness and speed sometimes under my control sometimes not) had inflated my sense of being, had created a sense that I had more, and more alive, nerve endings on a larger surface area. Wrought by this urban stimulation I went to see the Lygia Pape exhibition in the Met Breuer. This long, wandering introduction to a deliberate exhibition in an angular building is because my engagement with the Pape exhibition was primarily about movement; and movement implies, indeed requires, space and context. I went into the Breuer building and bought an annual membership (with a discount for being from far away), for I have been there before and will go again. Then I chose the stairs to revisit the curiously halted viscosity of Dwellings by Charles Simonds, a vestige from the Breuer building’s Whitney days. I climbed up to the floor with the Pape work and entered to a sideways view of the splash titling and image for the exhibition – A Multitude of Forms. The image combines uniformity – whiteness, children’s heads, all about the same size – and variation – in the way the white cloth dips and rises, in the very difference of each child. It is an exuberant and sobering image, conveying constraint, concealment, emergence, and movement. Only later did I realize that the image is a still from a movie which I viewed, and remember, as part of a course that included simple geometry – of the building, of Pape’s early work with the “geometric forms and pure colors” of the abstract art of the Grupo Frente; included, also, her later experimentation with naïve, semi-ethnographic film; and, finally, her return to geometry but now with pieces of unrestrained size and expression that jutted into the large spaces of the Breuer. The Breuer building enforces attention to perspective and the curator fully uses the building’s windows, ceilings, walls, and doorways to shift perspective from the singular art piece to the space, to the oeuvre, to other live bodies, to the outside in time and the outside in space, to both the merging of self through projection of self into something external and to the shocked separation of self from the exploitation of an image or a texture, both intended and unintended. My own movement was core to my viewing of this art, but, in addition, the movements of others became part of the art object in my viewing. One of the didactic plaques explains about the “Neoconcrete” tradition and intentions of Pape’s later work that “among the most influential outcomes of Neoconcrete art is the notion of an open work subject to the contingencies of time, space, and viewer participation.” It was humbling to find myself a textbook viewer of Pape’s art. I left the floor feeling like I had walked through a life, or in a long procession, more actor than spectator. Following a quick visit back to Dwellings, now merely landscape, I entered another show, THE BODY POLITIC, four experimental videos in dark places beyond an empty space: Five Easy Pieces; Phat Free; Love is the Message, the Message Is Death; and (down a corridor, separate) NoNoseKnows. In part because of time constraints, in part because the opening space seemed to offer me only two options, IN or OUT, and in part because I was already full, I gaped eagerly at the notices for each film and left the floor. Excision was easier in this geometric building than in the Rubin building.

I went down to the basement looking for an outlet to charge my phone. After an excellent cup of tea, I returned to the street, moving – mostly forward, sometimes sideways, sometimes halting, stepping back – and observing as if my path was still curated, almost as if each object was still art and I was still performing. * My interest in contemporary art and sensitivity to curatorial work has been deeply influenced by my artist friend, Patti Fox, and my curator/artist daughter, Pia Chakraverti-Wuerthwein. ** After years of railing against the singular “they,” I have been convinced that it is a more inclusive pronoun than s/he. It is also more commonly used than my logically preferred pronoun “ze.” *** I have no photographs of the Cartier-Bresson exhibition because photography was forbidden in that section. In the spring of 2012, I watched The Hunger Games. I was horrified by the story. I hadn’t read the books, though my daughter and nephew and millions of others had. I knew it had a strong female hero and so I expected to like it. But then I found that the core story involves a gladiatorial competition between children, where the winner is the one who survives. The weak, usually the youngest, get picked off first. What mind conceived of this horribly implausible game, I wondered. Never in history, to my knowledge, had any ruler or regime instituted such an entertainment. Yes, children were wantonly killed; yes, people were killed by (adult) gladiators; yes, child soldiers killed and committed atrocities in a “war.” But this pitting of children against children for entertainment made no sense, fit no pattern that I could think of, though it was a compelling story to follow and watch, much like a horror film. It wasn’t implausible in the way a superhero movie with bogus science is implausible, it was implausible because the social premises seemed off.

The only way it made sense was as an allegory. I moved back from the immediate spectacle of bigger children killing smaller children in a lush game world and considered only the most basic scaffolding. The story is set in the country/world of Panem which has twelve districts surrounding the capital. The districts are punished annually for a long-past insurrection by having to give up a child to fight in the Hunger Games. The capital is a beautiful city with wondrous technology, extravagant foods, fascinating clothing. All in all it expresses a climactic moment in human design and artifice. The richer districts are close to the capital and the poorest is far away. Typically, the expectation is that a child from the richer districts, usually one of the older children in the competition, will win (killing or otherwise out-surviving the others). So, with what framing could I find children surviving by killing or out-surviving other children plausible? Looking at the structures of my life, I am close to the centers of power and wealth, not geographically but in class terms. I enjoy some of the ease and luxuries that are increasingly taken for granted, and often further rarified, in those centers. My children have tremendous access to opportunities of various kinds. No, of course, they aren’t like the competitors of The Hunger Games, my mind shies away from the thought, but out there are children, even in the US, who have much less, and further out there are millions of children among the 20 million people who are at risk of starvation, right now in 2017. Our children do not choose these roles. It is as adults that we acquiesce to these structures, with those of us who are closest to the centers of power and privilege acquiescing the most. It’s very difficult not to acquiesce as an individual. The system supports, and is supported by, a web of daily tasks and pleasures. I could pay more taxes. I could give more money to worthy organizations. I could work in public service jobs. I could volunteer. In all these cases, my individual actions can easily be lost or get wrapped into the same-old. It’s not just a case of feeding the twenty million enough that their dead bodies don’t saturate our newsfeeds; and, then, once this crisis is past, we would leave them to a deprivation that is one notch above death. As an allegory, a plausible one it turns out, The Hunger Games helps us see the problem in our own lives, but it doesn’t help us much with a solution. In Collins’ trilogy, Panem’s socio-political structure is maintained with hidden (and not so hidden) violence and trauma, and then is, itself, overturned with extraordinary violence and trauma. We have our own hidden, and not so hidden, violence. But I cannot hope for the extraordinary violence that drove change in Panem. So, in the dull way of ordinary work and long-term trajectories – not just of policies and numbers, but also of relationships and accountability – how do we, in the US, look past one or two elections (2018! 2020!) to a larger, longer-term shift from the inequalities and hidden (and not so hidden) violence of our world? How do we work for this shift across political boundaries? Or can we hope only to hold back the worst extremes? Twenty million people are facing famine now. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed