|

For the last four months, I have been in Chennai, living with my brother and his family, helping take care of my mother who has terminal cancer. This has been a new life for me in many ways: far from my home in West Harlem; reestablishing and deepening bonds of affection with my brother and his family; inverting more fully, with affection and irritation on both sides, my child-parent relationship with my mother; and touching that line between living and dying that is always present in every one of our lives — ‘living is dying’ is a startling truism — though mostly we remain unaware of this illusory line, and when we are forced to face it we tend to fear it, or pacify it by placing it as a central mystery in spiritual or natural cycles.

Death as a physical event is ordinary. Death as the end of consciousness is terrifying. There is no further dawn, or at least most of us don’t know that there is dawn after death. This is true even for those of us who have grown up with rebirth and reincarnation as commonplace scaffolding for being, meaningful and effective in their own cosmological register. Most, if not all, have no consciousness, no corporeal memory, of a dawn after death. Yes, dawn recurs over and over for those who live — I’ll see the sun rise again, ‘this too will pass’ — but is there dawn after death? I can have faith that there is dawn after death, but I don’t know it. I may never wake up again; certainly this body of mine will not wake up again. The hope immanent in that metaphor — dawn after death — may just be a fantasy of this consciousness, now, that will die. In itself, rationally, there is nothing disastrous about consciousness ending. Pain may be grievous. Losing someone who is part of one’s emotional universe feels like losing a part of oneself, but a self remains to mourn that loss. Injustice and betrayal may feel like mortal wounds, but short of death, a self remains to feel the hurt, the anger, the debilitation, the shame, thus to be alive. Until my current experience of watching my mother live with her fierce energy, her obdurate independence and fierce though momentary pleasures, her recurring flashes of charm and tenderness, her sudden humor amidst her sharp changes in lucidity, until this current experience, I pacified death by drawing wisdom and succor from evidence and accounts of natural and spiritual cycles. But recently two things infiltrated my foundational calmness in the face of death. First, the smell of parsley cooking in my sister-in-law’s kitchen drew a very specific longing in me to cook one of my stews in my NYC apartment, with fresh parsley and fresh lemon thyme. My nose and stomach harked into that future: when I get home, I’ll smell that parsley cooking in my stew, in my home. The second infiltration came from Dylan Thomas’s poem “Do not go gentle into that good night,” one of his best-known poems. I can’t remember how it popped up on one of my screens a week or so ago. At first reading the poem seems to be calling for a last barricading against death. But after my recent reading, the poem slowly turned in me. Now I read the poem as a raging for life, not just for life too quickly past, nor for life too quickly passing, but for life now, living as dying, dying as living. Live fiercely like my mother does. “Rage, rage against the dying light,” sounds like an honoring of the last, frustrated fulminations of a dying consciousness that struggles but must slowly fade, and it is that. But I also found the energy of the poem coursing in me, and I see it coursing in my mother. Yes, there is frustration and fear as one part of my mother’s life after another slips away, more and more with no possibility of another dawn. Yes, this is happening throughout our lives. In the Japanese ichi-go ichi-e, each moment happens only once, each moment has no future dawn. Dawn, dusk, death pass quickly in each moment. This is palpable and ordinary if we dwell on constant change, but mostly we live our lives with the experience and expectation of regularity and continuity, the sun will rise again, spring will come again. In terminal illness, the irrevocability of change glares. This is gone, that will never come back. Each quick dawn is smaller, more fleeting, each smile, each lingering step, perhaps the last, each acquiescence to sleep, still only sleep, not death. When my mother’s smallest, most fleeting dawns cease, I will cook with fresh parsley again in NYC. Is rage in the face of death impotent then, an impotent struggle against the inevitable end of life, better to replace rage with meditative calm among those cosmic — natural and spiritual — cycles? The simple answer is that rage, the full living of each moment, however waning, is part of those cycles, no false choice there between one and the other. The less simple answer — fraught and agonistic — is that each lost dawn is ok if you know you’ll see or feel or hear another dawn, but when each lost dawn narrows conscious time to that point at which consciousness ceases — what dawn lies beyond that point? — the terror is real. Palliate the terror, but the terror may not simply be palliated away. One of my mother’s greatest gifts to me and the world is her joy of life, her unabashed vigor as she loves, laughs, dislikes, argues, fights, never shrinking, even now with her tired mind and frail limbs. I marvel at that vigor but to see her fully I cannot shy away from the contrast between my imagining parsley cooking in my West Harlem kitchenette again — a plausible future, wafting from my delusion of continuity — and her prospect of what dawn, what smells in what kitchens? At that line between living and dying, in that gap between the possibility of parsley cooking again and all possibilities as ephemera in a possibly meaningless unknown, in that space between delusion and fathomless uncertainty, Dylan Thomas’s poem exhorts, “rage, rage.” Live now, live now! Live now, live now, my mother’s life proclaims. Dylan Thomas chose “rage, rage” — the words are mad and measured, the sound beats out, and beats against, time — but in his calling for, calling forth, that crazy human consciousness of life, he could as easily have written “laugh, laugh against the dying of the light,” or “love, love against the dying of the light.” Just live, live as long as you touch this life and this life touches you.

0 Comments

My daughters have gone back to their adult lives. A period of reconnecting with them and friends over the winter holidays has closed. Most memorable were walking by the ocean and in the desert; eating and drinking – salad with fennel, chile con carne con butternut squash, lamb stew, chocolate-cherry-cayenne gelato, ramen, molcajete stew, candied ginger, yucky trail mix with chocolate chips, esoteric cocktails, superior Korean plum wine, water, and so much else; conversing with friends, from our neighborhood and far away, who came to our home, or invited us to theirs, or met us over some interesting food or drink, or chatted with us on the phone; holding on to family who called and skyped and said, once more, “we’re here, you’re part of us”; realizing and proclaiming that taking photographs just adds to the fullness of loving life and wonderfully – meaning full of wonder – having three new lenses with which to experiment (thank you, Milu!); and hearing new music, and dancing – gosh, listening to Yasmine Hamdan (La ba’den), Moses Sumney (Plastic), Rapsody (Knock on my door), Thundercat (Walk on by), Ibeyi (Deathless), and Kamasi Washington (Truth), in that order, and so much more, and then reggaeton ringing in my ears, moving inside me (thank you, Pia! … and Frank, for playing the reggaeton all the time…).

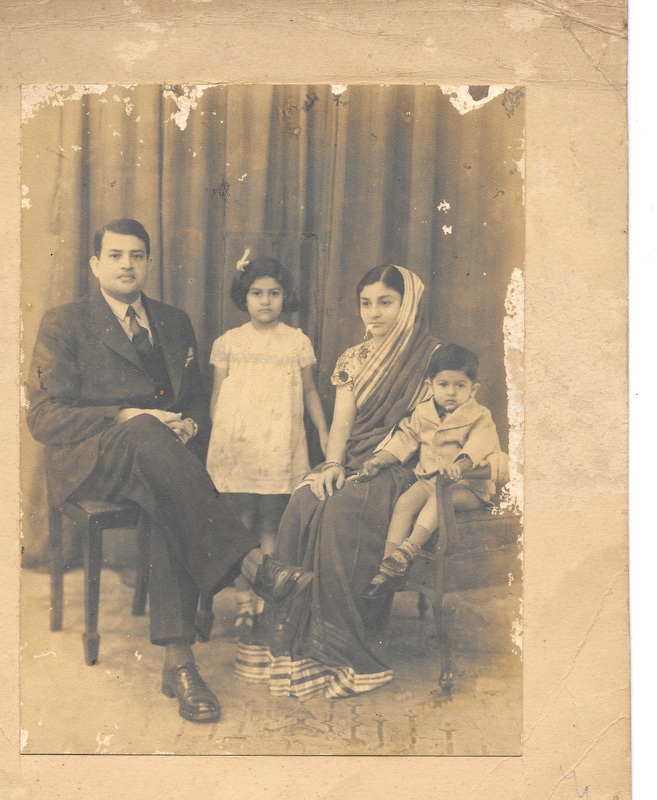

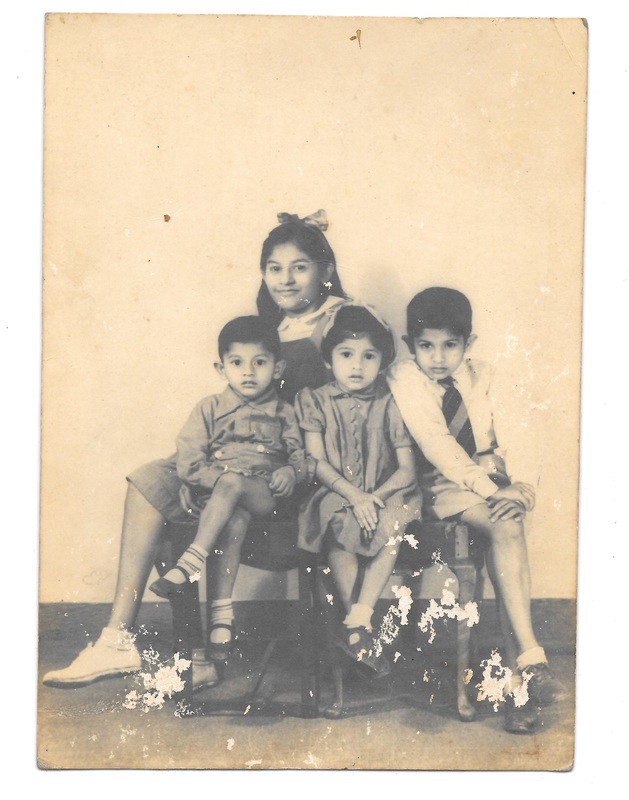

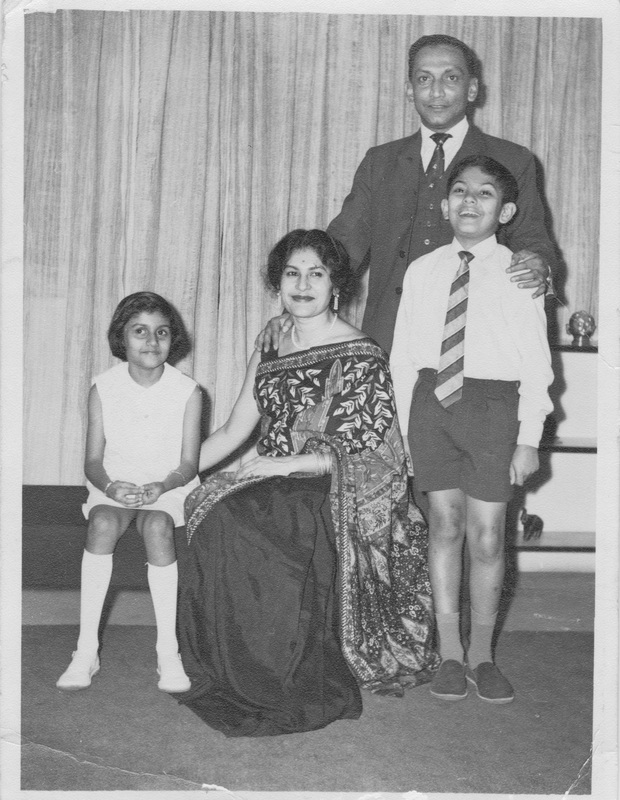

This period of reconnecting came at the end of an odd year, one that was marked by mind-numbingly dispiriting politics, deep existential challenges for me and several people close to me, and some fantastic new adventures (including, in starring roles, sea hares, osprey, bison, whale sharks, sea lions, and me as a skater) in stunning environments (including the highlands of Montana and Wyoming, the ocean around Baja California Sur, the desert east of San Diego, and the long paved promenade by the ocean that extends from the Pacific Beach pier to well beyond Belmont Park in San Diego) and restorative trips (visiting dear family in India, and dear friends and family on the East Coast). 2017 – odd, dispiriting, challenging, adventurous, restorative – is over! Renewed by the gifts of the holidays, my priorities for 2018 are all action — publish, write, make some money, engage in political action, and be fully myself while figuring out my life as an empty-nester. In a couple of days I will go to Under the Volcano (UTV), a writing workshop in Tepoztlan, Mexico, that focuses on global literary fiction, poetry, and nonfiction. I plan to use that time to ground an intention that is already alive – to be happily aggressive and ambitious in my writing life! This year I will publish my first novel, Night Heron, or move it substantially into a publishing pipeline. In theory, five editors (three in the U.S. and two in India) are reading my work. I will send more submissions this month and early next month. If I do not have a major breakthrough in mainstream publishing by the end of May this year, I will self-publish Night Heron, and draw on friends and colleagues all over the world to promote it. That means some of you! This year I am giving up bashfulness with regard to my writing. I am ready to move on to my second novel. I have already written about half of the first draft. I have ideas for a third and possibly a fourth novel. I know, confidently, that writing is not about writing one perfect novel. It is about writing the best first novel one can, and then moving to the best second novel, and so on. The first cannot be allowed to cannibalize the second, the third, the whisper of a fourth. When you will know me as a fully-fledged writer, if I live long enough and write fast enough, you will know me as a writer of several splendid novels, each the best for that period of my writing. After returning from Tepoztlan, I will work again, briefly, on new submissions of my first novel. Then I will turn to other things until May, only responding when asked for more, and editing when invited by someone with serious interest. I will keep writing my second novel, Pretty Lights. Stay posted. Amidst writing and pushing to publish, I will also return to political activity. The 2018 elections are coming. I will be contacting stalwarts who, throughout 2017, continued to work on building enthusiasm and commitment, which effectively has meant sharing knowledge and sustaining hope that change is possible. I will be active. I am writing this here so you can hold me accountable. Perhaps, even, you might join me and others in working to flip Congress or in some other way to build a social, political, and economic system that is deeply and genuinely more fair. The last thread of action is about being, which is active. Our children have grown. Our home has two older adults who “have their lives back.” Our time, our nights are our own again. Our meals are complex again (actually now they become even more complex when our children visit!). Our respective work no longer needs to be contained, nor is it a guilty escape. We’re two across the dinner table. The last time we were consistently two at the dinner table was about twenty-four years ago. We’re young old people now, or old young people. I’m a Fresh, Old Voice, after all. A lot of this is new to us. We’re adventurous, so new is good. We’re also yoked. We pulled together well when we carried the children; we still pull together well when we carry the children. But most of the time now we don’t need to carry the children. So our separate, respective unruliness is back, which makes the condition of being yoked really hard work. Being active this year, then, includes being fully myself while also paying attention to my partner and the mechanics and affect of that pesky yoke. Publish, write, make some money, engage in political action, and be fully myself, though yoked. Happy Birthday, Mom! -- by Arjun Chakraverti Mom was born in February 1932, the eldest of what were to be four children. Her parents were what we would today consider a strange mix of Indian and Western. Her father, born in 1903, came from a Calcutta family of means. His father had been a District Judge, which was a position of great authority and influence at the time. His mother came from one of the 3 families that ran the Kalighat temple. Like others of his time, the Judge was a male chauvinist who believed that a woman’s place was in the house. His wife was made of different stuff and using the little streedhan (women’s wealth, usually in the form of jewelry) she had, bought a nice plot of land in the marshlands and forests of South Calcutta at the turn of the century for the seemingly insignificant sum of 108 rupees. The judge was livid with rage as she had made the purchase without informing him but he did condescend to build a house on it, a house which saw the odd adventure such as the Viceroy’s daughter falling off her horse in front of the gate and being revived with a glass of milk from the judge’s feisty wife. Eighty years later the land, when sold, was to prove a godsend for the family. I still bless Tarangini Devi for her foresight and gumption. My grandfather was the younger son of the judge and grew up to be a tall and handsome man with a flair for literature and the arts. He studied at Presidency College Calcutta, arguably India’s best college at the time and was selected to join the Imperial Bank of India as a Probationary Officer, in what was only the second batch of Indians allowed into what was hitherto, a “whites-only” domain. The Mookerjees hailed from a village called Bhablagram in what was then 24 Parganas district. Bhablagram adjoins Basirhat on the Ichamati river and is very close to the border with Bangladesh today. The Bhablagram Mookerjees are a well-known family, the best known scions of which are the famous industrialist father-and-son, Sir Rajen Mookerjee and Sir Biren Mookerjee. Although the family was westernised, it was also obsessively, almost chauvinistically, Bengali. My grandfather, in all his years of travel and stay in North India, never picked up more than a smattering of Hindi. He did not see why he needed to, when he could make do with Bengali and English. It was therefore, unusual, to say the least, for such a person as my grandfather to be married to Nilima Banerjee from a well-known Bengali family from Allahabad. She was as fluent in Hindi as he was in Bengali. She and her sisters spoke Hindi in both the Sanskritised and Urduised versions. They sang Thumris and Kajris. In fact, Nilima’s younger sister Ila, used to sing for a radio channel of the time. Their food was different, a hybrid of Bengali and UP cuisine, of which the vegetarian dishes I still love. The Banerjees had also penetrated “Bollywood” in its early years. My mother’s maternal uncle, Sachin Banerjee was a character actor of note in the forties, fifties and sixties. The Banerjees also had imbibed some UP-style prejudices, especially with regard to color and ritual purity. Nilima’s elder sister never ate food cooked by a non-Brahmin …. and she died in the 1990s. Ila had no such prejudices and Nilima, who had an untimely death in 1946, was probably somewhere in between. These characteristics were each to find a place in Mom’s psyche, contradictory though they may have been. Above: Rita Mookerjee with her parents and brother in Lahore, 1939 Since the Mookerjees were very influential in Calcutta, certainly by the time Mom was born in 1932, she was granted admission to the best girl’s school in Calcutta, Loreto House. She already had a couple of cousins there, Biren Mookerjee’s daughters. However, my grandfather steadfastly refused to shift from the ancestral home at Purna Das Road so she went home to very Bengali surroundings every day. Loreto had a profound impact on her in terms of her world view, her English, and her fascination with Catholicism. She studied a short while at the Loreto boarding school in Darjeeling as well and in time her sister was to study at Loreto House, Loreto Simla and Loreto Lucknow and my sister was to study at Loreto Delhi, Loreto Lucknow and Loreto House, Calcutta. Her father had a transferable job which took him to places as far apart as Chittagong and Lahore. While at Lahore in the 1930s and 1940s, she studied at the Sacred Heart School but whenever he returned to Calcutta, she went back to Loreto. My mother met my father three times before they were married. The first time was at a marriage in Agra in 1935 where the two of them were “Neet bor” and “Neet Kanya” (miniature/pretend groom and bride), a rather odd custom that I have seen only among Bengali Brahmins. Many years later I was to be Neet Bor too and some old-timers started speculating on whether I too would marry the Neet Kanya. Mercifully for the lady in question, that didn’t happen! The next time they met was in Patna in 1952-53. My father had just returned after several years of flight training in England. However, the Indian government had not purchased the aircraft they were to fly so all the pilots were sent off on forced leave. He did get to dance with her at the Bankipore Club but declared her “fat” and a “spoilt brat” and said he didn’t want to have anything to do with her. Maybe there was something in what he said. My grandmother, Nilima, had died of meningitis in 1946. If she had been in Calcutta, the chances are that she would have lived, as Calcutta had modern facilities, including antibiotics. As it happened, she was in Allahabad and although the medicines were sent for, they reached too late. And so it was, that at the age of fourteen, Mom effectively became the mother of her siblings as well as her father’s hostess. Her father doted on her and she went with him to parties and organised his parties for him at home or at the club. She got used to getting her way with him so when she met this cocky young Navy pilot she treated him with cold disdain. She was used to hobnobbing with Generals like Thimayya and Thorat so a mere Lieutenant was below her station. The third time they met was in Lucknow in 1956. This time, she had matured (and slimmed down) so, with some encouragement from General Thimayya, among others, she decided to say “yes” to my Dad, now a Lieutenant Commander. Above: Rita Mookerjee, 1956 Above: Tuhinendu and Rita Chakraverti, 1957 The life of a Naval wife was very different from that with the Imperial Bank. Where she had had dozens of servants, now she had only a few to help with the essential women’s work of cooking, cleaning, and childcare. Moreover, while she had travelled all over North India, she had never seen the South and she was to spend most of the next twelve years in South India. She took to it pretty easily and gave birth to two children in the process. Despite her many strengths, one thing she was NOT good at was languages. It has always baffled me as to how she never learnt Hindi, despite being born in Allahabad to a Hindi-speaking mother and having subsequently lived all over North India. In fact the only three Bengal postings her father had were to Calcutta, Jalpaiguri and Chittagong. As against this, he was also posted to Lahore, Simla, Agra, Lucknow, Benares, Gorakhpur and Patna. She was later to marry a Hindi-speaking (Bengali) husband (whose recent ancestors hailed from Ajmer and Aligarh) and produce a Hindi-speaking son but her Hindi borders on the comical, peppered with terms like “Ghode ka anda!” (“Horses egg”) or “Na Hathi!” (~ “like an elephant!”). These terms are literal translations from Bengali and mean absolutely nothing in Hindi. I was to discover, many, many years later, just how much she was loved in the Navy. My father was a hard taskmaster and a rather gruff person, but she more than made up for it. And then, as her children grew up and she had more time on her hands, she decided to go back to college, do a B.Ed and teach. She was more than 45 years old when she finished her B.Ed but she got a Gold Medal for it and began to teach, where else but in her Alma Mater, Loreto House in Calcutta. She retired from there in 1994 but continued to teach, now in Chennai’s best school, Sishya. And when she moved from Chennai to Dehradun in 1998, she continued to teach, now at the Doon Girls School which is, among other things, a preparatory school for Welham Girls School and Mayo Girls School. In fact even as I write, this 25th day of February, 2016, Mom will be celebrating her eighty-fourth birthday teaching little girls the nuances of the English language and culture. Their parents come from Badaun, Bahraich and Bulandshahr and their constant refrain is “Mem, meri beti ko bhi Mem banaiye!” They couldn’t have asked for a better teacher. My sister and I know. We were put to the grind as children ourselves, not just to improve our English but our deportment and table manners as well. All so that “when the need arose, we could conduct ourselves properly with the Queen!” And so, on your Eighty Fourth Birthday, here’s wishing you many, many happy returns of the same and thanking you ever so much, for everything you have given us! About My Mother, On Her 84th Birthday -- by Meenakshi Chakraverti “My father said he would send me to Girton College,” my mother told me when I was growing up. One reason that didn’t happen was because her mother died when she was fourteen and she took on responsibility for her three younger siblings. This story existed side-by-side with “My mother cried when the family of an eligible, handsome man of twenty-five refused me because I was only ten years old, too young to be his bride. If my mother had lived, I would’ve been married by fifteen.” I never found these stories contradictory because my mother is seamlessly both the woman who would have gone to Girton and the woman who would have been married off at fifteen. Throughout my life she has combined constant intellectual curiosity and independence with quaint, and often annoying, conservatism on especially gender issues. She was born in 1932. She is now eighty-four and just returned to teaching at the request of the school in Dehradun where she has taught for almost two decades. She follows and discusses politics brilliantly, loves reading, and claims she wanted to be a physicist. When a colleague once asked me, many years ago, whom I admire most, wryly because of the triteness of my response, I said, “My mother.” She enjoys life, I explained, and she’s brave, and she laughs, all this with an unwavering selflessness in relation to her children. She goes out to life with inquisitiveness and delight, and a wicked sense of humor. She lost her mother at fourteen, and took on responsibility for her two younger brothers and younger sister. My brother and I often felt that the two youngest, an uncle and an aunt were almost Above: Rita Mookerjee and her siblings, 1946 our older siblings, and they often talk about her strictness (some of the stories are hair-raising) but always with loyalty and love. We all make fun of her and we all laugh. Perhaps my second greatest gratitude to her is for her teaching me how to laugh. Her father worked for the Imperial Bank of India, which became the State Bank of India after Independence. He was a single parent to his four children for eleven years. He died when my mother was twenty-five and his youngest was sixteen. My mother and her siblings adored him. Above: Rita Mookerjee with her father and siblings, Simla, 1951 Oddly, while she kept telling me that women are uniquely nurturing and kept trying to prepare me to be a good wife (among other things by wanting me to practice serving my future husband by making my brother’s bed – which I refused to do) and mother (by training me in practices of abnegation, for example by making me allow everyone else to get their choices first), her stories about her father gave me the most clear evidence that men can be deeply nurturing and that parents can work outside the home and be fully parents. Her father was posted in different parts of India, so my mother lived in Lahore, Agra, Patna, and Lucknow, among other places. She speaks of Lahore, now in Pakistan, with great fondness, with memories of its graciousness, and of the generosity of their Muslim neighbors. But the stories were not simple, nor simply sentimental. When a Muslim neighbor, whose little daughter was my mother’s friend, sent my mother’s Brahmin family fabulous food for Id, my grandmother gave all of it away. My maternal grandmother’s family had lived in Allahabad in Hindi-speaking North India for a couple of generations before my mother was born so, in addition to her childhood peregrinations across the northern swath of British India, her maternal influences exposed her to the graces and manners and Hindi-Urdu language of the north, much of it intermingling cultural provenance that some would distinguish as “Muslim” and “Hindu.” My mother grew up cosmopolitan even though she did not leave India until 1985 (at the age of 53) when she came for my graduation from the Master’s program at the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton. Her father’s family lived in Calcutta and came from Bhabla, a small village that she visited as a child. Her father spoke fluent Bengali; many of her relatives did not speak much English. She was very comfortable sitting in wholly Bengali environments and adapted her whole demeanor to the social, emotional, and intellectual rhythms of that language. She spoke and read Bengali, but she went to “convents” that European nuns ran for expatriate Europeans and elite Indians. The idioms of nineteenth century and early twentieth century England form the bedrock of her fluent English, a colonial legacy that echoes in my writing, even after thirty-five years in the US. Her father worked with Britishers and, when her mother died, she played the role of his hostess and companion at parties – from the age of fourteen. So she developed a part-syncretic, part-revolving habitus that includes proficiency in Bengali, British, and North Indian ways. It is completely normal to hear the cadences of my mother’s voice, and her gestures, change depending on whether she’s speaking Bengali, English, or (somewhat Bangla-fied) Hindi. Like her father, who worked for a British bank and who loved the language and many of the practices of the British, but who also loved reading Bengali literature and wore khaadi in resonance with the Nationalist movement, my mother is both fiercely Bengali and bemusingly Anglophilic. In a further variation on her easy living of a wide cultural range, my mother is simultaneously a devout and practicing Hindu and one of the most Catholic people I know. To some, these might look like contradictions. They don’t look and feel like contradictions to her and they haven’t looked and felt like contradictions to me. Her father died a year after she married my father, right before my brother was born. My mother always speaks, with immense gratitude and love, about how my father’s family helped her take care of her two youngest siblings and welcomed them. With my father, she travelled to new parts of India, to the South and along the coastline, making homes for him and us in Coimbatore, Cochin, Coonoor, Bombay, and Goa. She reveled in the multi-culturalism of the Navy and she and my father enjoyed exploring new places. My parents’ marriage was tumultuous, with much love and new adventures, but also great challenges. Above: Rita Chakraverti with her husband and two children Around 1975, my mother found she needed to work. A couple of years later, at the age of 45, she decided to go back to college to get her teaching degree. I’m smiling as I write that she got a gold medal for that course! She’s been a teacher since then and, as I mentioned early on in this blog post, she was just inveigled back into teaching. She turns eighty-four today, February 25, 2016, so I’m writing this piece to celebrate that birthday. She has so much more living ahead in this life, and luckily for those of us who have a rebirth mindset, what doesn’t get explored in this life can be explored in future lives. I can well imagine my mother erudite, laughing, loving, and curious on some distant, off-planet colony! … And, for those of you who might be wondering, my greatest gratitude to my mother is for the security her love has given me all my life. I know that she would move heaven and earth, or would try to, to make things right for me if I needed it. Even today, when I am mature (heading into post-maturity!) and independent, and she is eighty-four. It’s ridiculous, but true.

Note: I was inspired/pushed to write this blog post by my brother who was inspired by a lovely blog post by a Bengali/Bangladeshi friend who was celebrating her mother’s birthday. I’ve suggested to a Pakistani friend that she write a blog post about her mother. There’s something about blog posts about parents that makes borders irrelevant and history larger. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed