|

Dharma and Buddha nature, or layering is a form of propagation

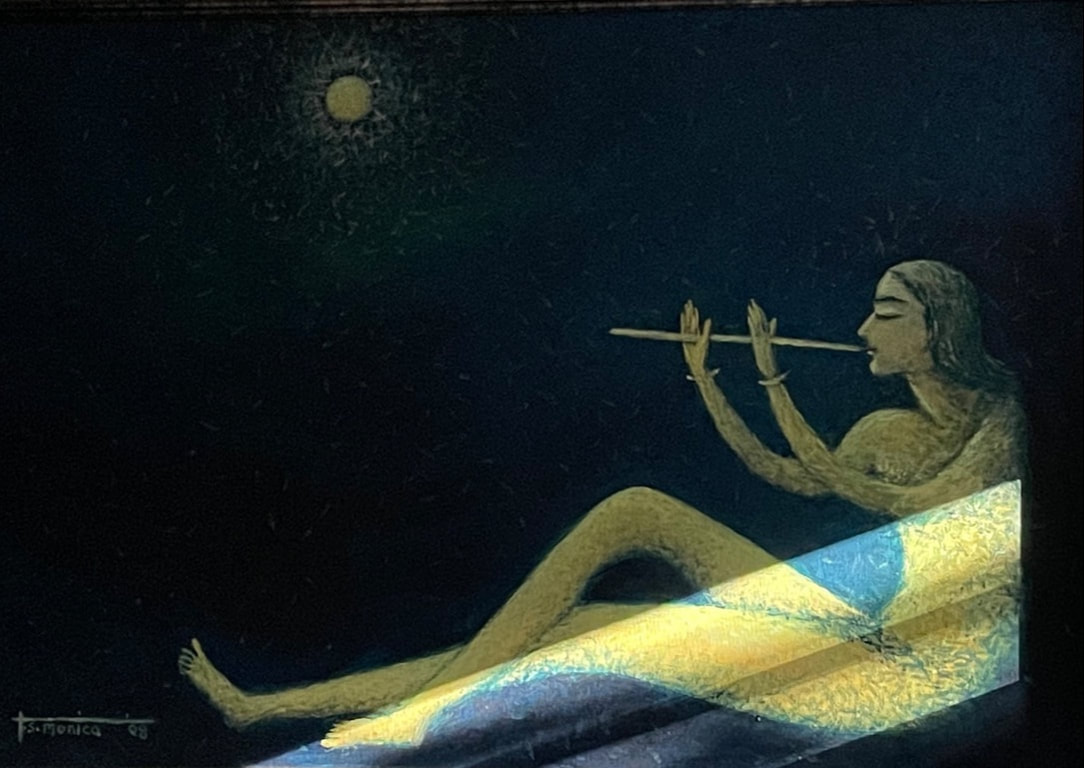

A few weeks ago two different thought clouds clapped against my mind like disparate cymbals, but with no violent residue, no headache. The sounds — the force of each — struck moment after moment of my mind, each confused with the other, and resounded, ringing with joyfully learned, naturally moving polyrhythms. There you have it, the word “nature,” both the ground from which roots draw the substance of life and the material of the roots and tips, indeed the air of respiration. Layering is a form of propagation, Elaine Ng, an artist and my friend taught me. When I told her about how the last months have been, for me, a popping out of a multi-year experience of bewilderment as one life structure after the other changed, some by my choice, some fated by the course of my own and others’ lives, some changes woeful, some joyful, the whole bewildering, I concluded that now, after popping out, I feel like a grown and aged baby. A rooted seedling, she responded. A perfect metaphor I exclaimed, a rooted seedling! I went on to further describe the wending of my aged babyhood. She listened and listened; I’m long-winded. And then she said, I’m revising my metaphor. I looked skeptical. What could be better? And she conjured up and recited a truer metaphor after all. Layering, she said, layering, which is a form of propagation. If you’ve read or heard me speak about my first novel, you’ll know that layering is the ground I walk on, the air I live in, even — to hold no exuberant excess back — the thermoclines I ripple through when diving. (Hmmm, there are no thermoclines in my first novel.) Hunh, I responded curiously and unusually pithily. I said seedling, she said, but you’re a grown plant. A grown plant can get knocked over by something outside itself. It may fall over, be driven to touch the ground. In ideal circumstances, the fallen plant will shoot roots into the ground on which it lies. It’ll draw from the remaining strength of the original plant to grow again with new roots, its tip growing up into new life. After a while this new growth is independently strong. The original plant does not necessarily die, but if you cut it off, the new plant will still live and grow. I’d never known anything like this, so I looked at her with wonder. This is layering, she said, a form of propagation. Really? There are real plants that do this? Is this like the banyan tree? No, I’m not talking about aerial roots like the banyan has, nor about the bowed rooting that is part of the normal growth practice of forsythia and cane plants (mind you, through all of this I was gaping in my mind, if not on my face, an amazed and delighted gaping). I believe, she said, offering the caveat that she is no expert botanist, that “layering” implies that something external forces the plant to the ground. Do you have an example, I asked, a plant I may know? Time, she said. No, she did not say time. Thyme, she said. Thyme! Of course. So what does all of this have to do with dharma or Buddha nature, beyond all of these sharing a space in my mind, a time in my life, that morning of October 21, 2022? Well, let’s start with dharma. I am not referring to what is commonly understood as dharma in Buddhist traditions, but rather a Hindu notion of dharma that I learned as a child and youth. As I absorbed various inflections of “dharma” through stories and philosophical writings, I came to understand it as who one is, living who one is. Your dharma is directly related to who you are, your dharma is to live who you are. This notion is complicated. It’s been pressed into justifying socio-economic stratification in ways which have spilled into brazen constraint and cruelty, as when Hindus have insisted on some version of: you must, you can only, live your caste or lack thereof — your high status, your low status, that’s who you are, that’s your dharma. However, in the stories and philosophical writings I encountered, there are enough examples in which “dharma” is not bound to structural position. I found enough boundary-crossing that I came away with a notion that can expansively hold a complex mess of being human. But then one could ask: do you mean that serial murderers can justify their practice of killing people by saying they are living their dharma? That would suggest a notion so immoral that it has no meaning beyond willful, contingent idiosyncrasy. Technically, yes, a serial murderer could say that. But my dharma, and many of yours too I suspect, includes stopping harm to others, especially what looks like wanton murder, and so we’ll try to find ways or support ways — investigative, judicial, preventive, etc. — to do that. From this perspective community norms and statecraft may be viewed as the collective expression of recurrent and overlapping elements of individual dharmas, including dharma elements related to loving, sharing, seeking well-being, seeking domination, seeking overweening survival-to-immortality, destroying an obstacle, propagation, growth. But this kind of efflorescing, even rampant, dharma sounds very different from Buddhist notions of dharma which modestly propose a way to live with no, or at least less, suffering by giving up the delusion that if you get what you desire you will not suffer. The Buddhist way is taught in a combination of practice and precepts that often enough sound and feel prescriptive. Buddhist understandings of dharma — that I draw from my sporadic chunks of practice with Zen sanghas, and my mostly autodidactic reading and home practice of Zen and Tibetan Buddhist traditions — have both attracted and puzzled me. A mystical, Taoist aspect deeply appeals to me because it seems to hold the length and width of what is knowable and unknowable, but then when I read “when love and hate are both absent everything becomes clear and undisguised,” (Chien-chin Seng-ts’an, Third Zen Patriarch), I make that concise sound again — Hunh? Well, I’m not going to stop loving, so I guess I must focus on not hating, no dualism, so all love, all-all. And from there I’m back to trying to be good, to only love. Efforts to only love mean constantly denying or suppressing parts of myself, or feeling guilty, trying to be better. Not that trying to be better is bad, but denial and suppression invariably come back to bite me. The Buddhist teachers I read foresee that happening and tell me that’s no good either. Ok then, feel nothing, think nothing. That’s not happenin’! Then, on that same day as layering opened up and when I was feeling a nagging conflict of “shoulds” — including the insidious should not-should — around a personal dilemma, I read some pages of Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind for the nth time: “When there is no gaining idea in what you do, then you do something. … It is just you, yourself, nothing special.” Bingo! It’s my Hindu notion of dharma! Buddha nature is living who you are. Nothing special. So maybe greedy, conflicted, unhappy is who I am, so nothing further to be done, you might say to me. Maybe, I would respond. I can’t tell you who you are. I could tell you what I experience but that may or may not be interesting or helpful to you. But if you want to feel differently, be more comfortable in yourself, I do find the Buddhist path to the root of your suffering a helpful practice and exploration. Importantly it’s a living that has no end apart from itself; it both has a goal and no goal. From this perspective, fulfillment is not a levitating cushion of certainty. I’ve found the path laid out by Chogyam Trungpa, particularly in his teachings in The Truth of Suffering, helpful. His detailed description of the path of the Hinayana way to liberation from suffering starts annoyingly prescriptive and ends with illumination of a potential passage to clarity about who one is. Parenthetically, Trungpa’s teachings seem to contrast oddly with accounts of his un-Buddhist sounding lifestyle that apparently included womanizing and alcoholism. These may seem logically inconsistent, even hypocritical, but they are not inconsistent in the body, mind, and emotions of a human. This way of looking at it is not about justification, it’s about seeing all the parts.* Nothing special. Trungpa’s teachings, along with the backdrop of his life, are dramatically different from Suzuki’s austere expressions of his Mahayana way, but they converge for me on an understanding of life, of Buddha nature. This Buddha nature is nothing special; we all have it, we can all uncover it, and it’s not all one thing. I realize that many committed Buddhists may find what I’ve written here inaccurate or misleading. To them and to you, my dear reader, I say: find your way. This is where I am on my meandering way — sometimes dancing along, sometimes staggering with too much, sometimes taking the long way deliberately, sometimes levitating on that cushion of delusional certainty, sometimes the cushion collapses and I fall to the ground, and then LAYERING! Among the recent life changes that bewildered me, my mother passed away from pancreatic cancer. She was my remaining parent and caring for her in her last months turned my experience of life from living and death to dying and alive. Caring for her I became corporeally aware of impermanence, of how life falls away from body and consciousness even as we live as we are now. So here I am: new growth, energetically grounded in impermanence, uncertainty, and incompleteness. Alive. I can only live who I am, die who I am. Nothing special. * Is it too much, too extravagant, pushing limits too far to suggest that you read Rita Dove’s brilliant, lovely poem “The Regency Fete” in this context? AND I struggle with how this notion of dharma or Buddha nature can become a refuge, a delusion in itself, whether on the cushion or debauched like the Prince Regent or colluding, by commission or omission, in the collective injustices of one set of people upon another. Where is dharma there? Whose dharma? If I have the answer in one dimension, I don’t in another. Uncertainty, incompleteness, imperfection, nothing special. More meandering through dharma, vegetation, changing light, inconclusive living A couple of weeks after the above piece was first drafted, I looked out of my window and gazed at a tree — mostly yellow, some green still, a few bare twigs — glowing in the morning sunlight, and mused: if I am the tree, I can’t be the sun. But I can enjoy that light, let it warm me, feed me, enrich my living. And I can glow and be beautiful just as I am, making the beauty of my spread and my colors, just as I am. And perhaps someone like me will look at me and see that spread, those colors, my glow. I may not know it, I may never know that Meenakshi watched my leaves grow yellow and fall in yellow showers and loved me and felt her life enriched by me. It’s just the way I am, I live, until I don’t. These sentiments, projected onto and drawn from the tree and the sunlight, became conscious as I decided to continue reading Andrey Tarkovsky’s lovely Sculpting in Time. But first I dipped back into Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind and found myself reading what seemed to me exactly the description of my vegetative life that morning (though perhaps not quite obvious in this telling): “When you know everything, you are like a dark sky. Sometimes a flashing will come through the dark sky. After it passes, you forget about it, and there is nothing left but the dark sky. The sky is never surprised when all of a sudden a thunderbolt breaks through. And when the lightning does flash, a wonderful sight may be seen. When we have emptiness we are always prepared for watching the flashing…. If you want to appreciate something fully, you should forget yourself. You should accept it like lightning flashing in the utter darkness of the sky.” [Meenakshi’s added note: forget the should as well.] Of course that vegetative sharing of life with the tree came in the morning, in a time of glory and reflection. But then, that same evening, as I was lower, duller, I looked at that same tree that now, like me, felt night fall heavily. Another dog had pooped, another man had peed. A paper cup and a plastic bag lay in the speckled mud of the tree bed. If I were the tree I’d be wondering: where will my seeds go? (This tree has lovely large, dark clumps of seed pods.) Why do I even bother morning after morning, night after night? So this is living, it’s not all glory and reflection. I’m also reading Moby Dick. Melville names submission and endurance as womanly virtues, in one of his rare references to the female of a species; most such references offer soft contrasts to the looming, flailing masculinity of the more obviously active characters, indeed of the exploration itself. So, does the tree submit and endure? Is that its action and heroism? Inconclusion

0 Comments

|

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed