|

I listen to music as a non-musician, naively. Every listening, even a repeat, or much-repeated, listening is naive. Naïveté in listening is the foundation for the ecstatic luxury of body and sound when I am listening to music. Movement may or may not enter the act; body in stillness is still body, still hearing and sensing the reverberation that is sound.

I listen to a lot of music, infinitely different kinds. In the universes of music I have encountered — with ever greater density rushing past me, mushrooming, my body relentlessly naive — I have found only occasional spots that have stopped me short, but no, I will skirt around that path, it’s not interesting. Sound — the music I stay with, but sometimes even and consciously ordinary sound — may be just strung or dropped notes without words. Or: that sound that catches and holds me, that I behold so to speak, may be words that give histories, expressive consciousness of a sort, to the notes that run through them. In music, I listen to words as sound first, and as words after. Often I barely listen to the words as words at all. This is certainly true about words in languages I don’t know, but often this is true about words in languages I know as well. When I listen to the words, often I hear just a repetition or a phrase, sometimes I hear the wrong words, meaning the words I hear or place in that music are not the words that are formally part of that composition. When I listen to the words, however I hear them, I attach conscious meaning to that phrase of music, to that sound composition as a whole. Sometimes that meaning is fragmentary and surrounded by the corporeal and unconscious sensation of music on and in the body, and sometimes it dominates the composition. Whether scattered, ethereal, or dominant, the meaning permeates the composition, not in some completed or static way, but in a dynamic, evolving, and sometimes dying way. Returning from my digression into meaning, in the primary experience of listening naively, music as sound and body is meaningless. This post was catalyzed by listening to the music of Son Lux for the first time. I haven’t dared write about music before this because, well, I’m naive. But some days ago, I listened to Son Lux for the first time. Initially this was an unconscious listening to the background sound of the tumbling pictures and disorderly words of the film Everything Everywhere All at Once. The film is such an eye-popping feast of increasingly riotous movement and meaning that I didn’t notice the music until the credits. That’s a compliment to the synchronicity of the music with the psychedelic movements and meanings that lurch with the characters and their stories, between bills to pay, receipts to recover, hurtling stereotypes, a stunning range of emotional content, and much more. I only noticed the music, noticed the music as composition in its own right at the end when the score continued through the credits. Aha, this is interesting, I thought. I looked for and listened again to the most obvious track, the song This Is A Life, then bought and downloaded it. After listening to that song a couple more times, I got more curious. Who or what was this Son Lux? So I listened to the full score and loved it. I bought and downloaded all of the two hours. My first few listenings of the whole two hours in one sitting were gloriously naive listenings. There are some words associated with this soundtrack: a few songs with English words; one song with Chinese words; the titles of the songs; and the name of the group that composed this soundtrack using original and sampled music — Son Lux. When I first saw the name Son Lux, I assimilated the word “Son” with its homonym, “son” meaning male progeny. Of course, it’s an electronic boy group. Then as I listened to the full score the first time, the second time, “Son” became sound, and lux became the first syllable of luxury, sensuous excess. And that led to this first written reflection on music — indeed sound — as I hear it.

0 Comments

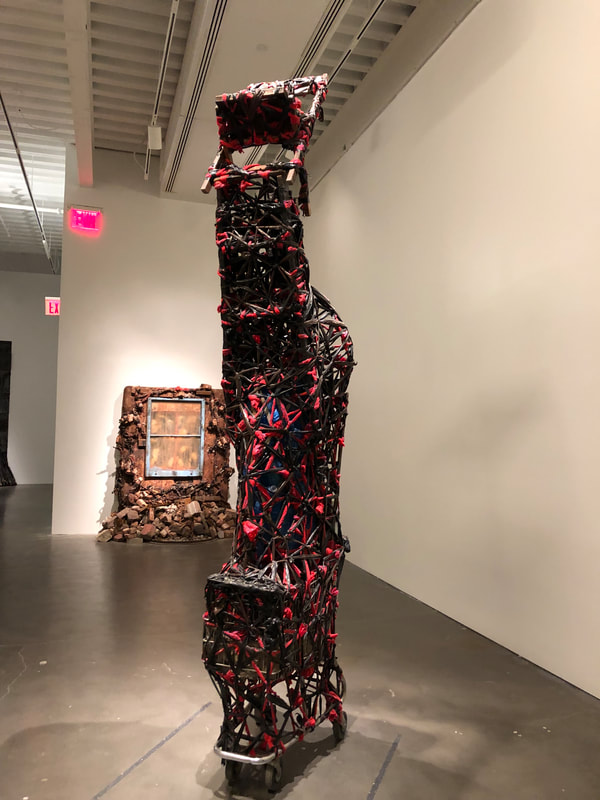

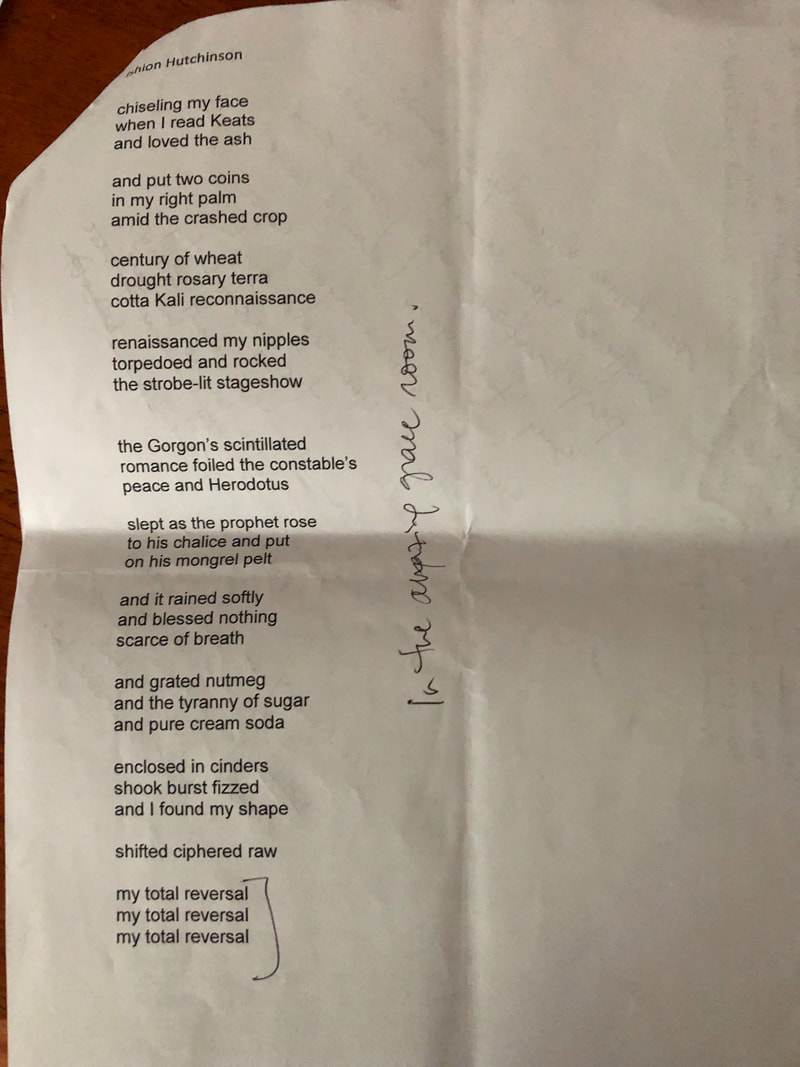

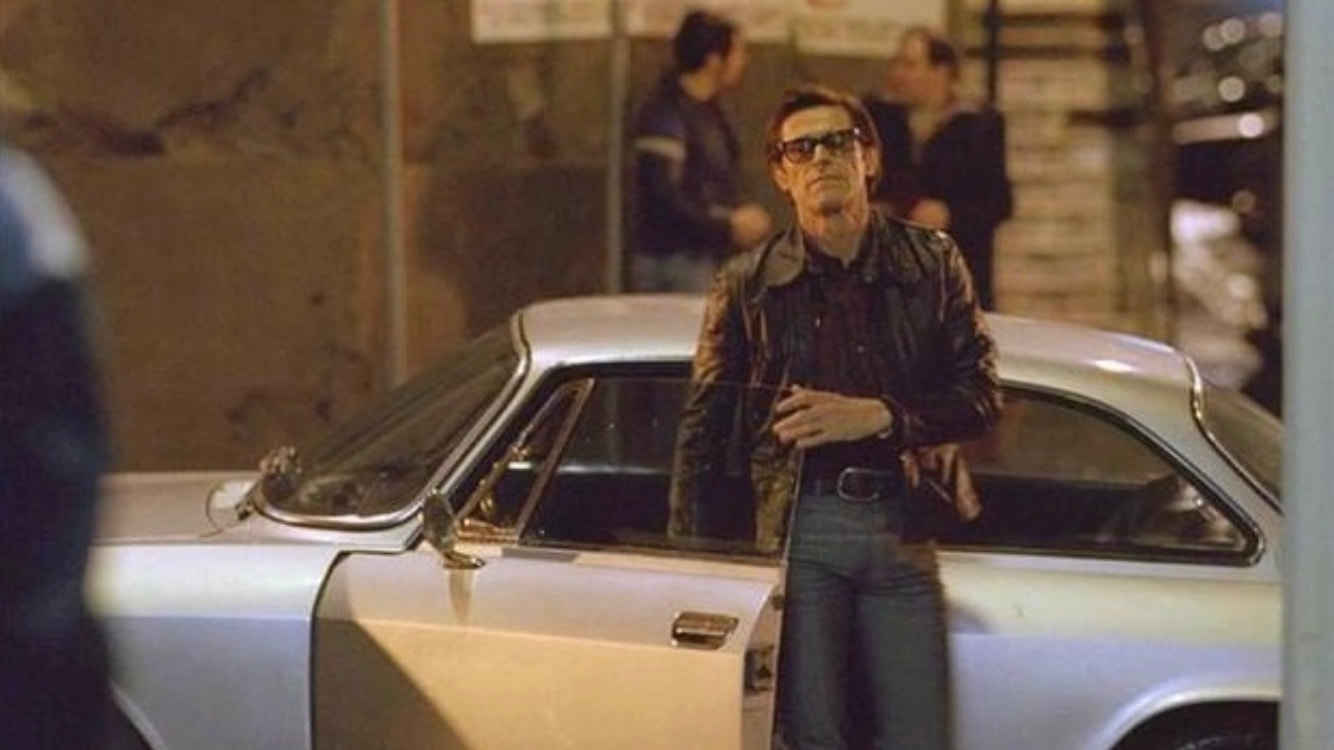

(Spoiler alert re the movie Pasolini) The sequence of Nari Ward, Ishion Hutchinson, and Pasolini just happened; there was no plan on my part. Nari Ward and Ishion Hutchinson were paired by the New Museum. Not unexpectedly, they were a good pair, or rather I found Hutchinson’s response to Ward’s art provided something like a blended glass, part mirror, part filter. More about that in a bit. I added Pasolini because I wanted to use my Metrograph membership; I could walk to The Metrograph from The New Museum, and Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini was playing at the right time for me to move in this way through the city. Interestingly, going to Pasolini also became the right movement for a kind of intellectual and emotional trajectory. Though this is often the case as we knit the past into some kind of coherence, in this case I struggled with making the sequence coherent, then forced a coherence, and then was struck by what came of and from the forced coherence. I went to The New Museum for the first time about two weeks ago because a friend wanted to go there and I’ve wanted to go there for a long time. We started on the top floor with Jeffrey Gibson’s kaleidoscopic work and I passed through his work, loving the color and the immanence of movement. Later, I passed through Hélène Cixous’ odd, insightful, and romantic essay on Gibson’s work. “A dislocation is at work,” she wrote. Then we went down three floors of Ward’s large installations and smaller, more compact, art in the exhibition called “We the People.” The making of art from found objects is not new but the poignancy of this exhibition lay in the bend between the mourning of pain and history, and the fertility and beauty of, somehow, life. I had not heard of Nari Ward before this and got a little uncomfortable when I heard that he is a Harlem-based artist and his art connects directly to dispossession, not only of the past, but directly in the effects of gentrification in the present. I moved into West Harlem in June 2018, an innocuous, older-ing, and brown woman. I belong here, and I don’t. I had noticed, when checking out the museum before I went there with my friend, that Ishion Hutchinson was going to do a gallery talk on Nari Ward’s work. When I asked if there were still tickets available for that gallery talk, I was told there were. I was stunned. I guess this is NYC. I said, if you don’t think they’ll sell out while we, my friend and I, go through the exhibitions, I’ll wait to see Nari Ward’s work before buying a ticket for Hutchinson’s gallery talk. They assured me there would still be places, and there were, and once we’d walked through and down all the floors, I bought a ticket for the talk. So, on Thursday, May 16, my hair freshly colored, I went back to The New Museum, and waited for Ishion Hutchinson’s gallery talk. Ishion Hutchinson, like Nari Ward, is Jamaican-diaspora African-American. He is a poet I much admire. He took us, a group of about fifteen people, through parts of “We the People,” with eloquence, diffidence, clarity, and kindness. He took us – none of us belonging to the African diaspora, though all of us share fraught histories with Nari Ward and him – through touching what ‘fugitive’ can mean in history, selfhood and art; through hearing the grandness of aspiration while living in “material fetishes of failed utopias;” through sensing, distantly – in our case, each of us, perhaps with some guilt, or shame, or desire – “an old resilience which is part of [Hutchinson’s] heritage.” He told us about the abeng, and made its sound with his breath, his throat, and his mouth – this was a generosity of sound, not just a performance or lecture – and related it to the artwork called Savior. The abeng, he told us, makes the sound of the fugitive. He lost his voice briefly after making that sound. He stood in front of the two pieces called Breathing Panel and, at the end of his prose response to the artwork, repeated, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe….” In that brightly-lit gallery, with chattering, whistling sounds from an adjoining artwork, with only one other African-American, a gallery attendant, in view, with one other gallery attendant who looked Latino, and me, a class- (and caste-) privileged South Asian-American, with everyone else phenotypically white, mostly women across a range of ages, I wondered who couldn’t breathe now, why couldn’t they breathe. Who is breathing? For how long? Then he took us to the large, dark room in which Amazing Grace was installed; “a womb, a slave ship, an ark,” he called it at the beginning and towards the end. He walked us, two-by-two and holding hands, through the stroller-ship-womb. He read his poem Sprawl and repeated “my total reversal” – the last three lines of the poem – more than three times. And then we were done. And I got him to sign my copy of House of Lords and Commons which he not just signed, but also inscribed with “a small, drifting raft” for me. I walked out into the sunny afternoon, exchanged cheery words with one of the outside guards, walked through Chinatown, got a text message from my daughters in which they laughed at my ‘culture-vulture’ day, got to The Metrograph, and bought a ticket to see Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini. On Instagram, I posted some pictures and wrote: it’s hard to call walking through Nari Ward’s work at The New Museum a pleasure, but perhaps one can call it a tenderness, an amazement at how beauty can come alongside, and from, ugliness and sorrow while underlying cruelty and pain remain cruelty and pain. Pasolini starts, if not right away then very early on, with explicit, aggressive, unlovely sodomizing of two submissive young women. With Pasolini, I seemed far from the fugitive grief and anger and grace of Ward’s work and Hutchinson’s words. There was abject or abjectify-ing sex, followed by ordinary domesticity and interesting, but cold, words. “Narrative art is dead,” Pasolini told us, “we are in mourning.” “Mine is not a tale, it is a parable,” he said, “I am a form, the knowledge of which is an illusion.” To Pasolini, it appears, I, Meenakshi, am a moralist, who neither seizes the right to scandalize nor feels pleasure from being scandalized. About a third through the movie, I wrote in my running notes: so far there is very little that one might call kindness, or love, or tenderness. I watched more sex -- this time apparently not abject or abjectifying, more a kind of revolutionary procreation in a reversal of desire -- between beautiful people, with a raucous audience within the film, and us, a quiet audience outside the film, with our own arousals and withdrawals. Pasolini sees his work as a revolution. “I’m asking you to look around,” he says, “and see the tragedy… … starting with universal education … which leads us to want … and not stop short of murder…. … an appalling tradition that is based on this idea of possessing and destroying.” * The tenderness came at the end of the movie, when Pasolini is beaten to death on an industrial beach and the movie closes with a “clip” from a made-up movie based on Pasolini’s last work-in-progress. In the clip, Epifanio, an older-ing man, and his young companion are trying to get to Paradise and Epifanio can’t go on, so the young man says, “The end doesn’t exist. So we just wait. Something will happen.” Obvious shades of Godot, but owned here in its own terms, with its own peculiar pathos. In the end, the tenderness comes from the unabashed living of, and looking at, life with all its ugliness, its earthiness, its longings, its sensuousness, its beauty of form and light and shadow, its flaws, and just life. In general, I prefer to look at, sense, and join joy and tenderness of a different kind, but I did feel the tenderness at the end of this movie. Then started the struggle of knitting the coherence of my past. In my head, I stared at the obvious challenges of colonialism, racialism, the cruelty and survival of color lines of history, simplistically pitted against normative sexualization, scandalous desire, the intense ambivalence – intimacy and violence – of sex, and the cruelty and survival of power lines of history and didn’t get far, actually didn’t get anywhere, so retreated to higher abstractions. This is what I found. In Pasolini, there is no redemption, no desire for redemption. There is (only?) a wild grasping for freedom outside a cruel system that must be broken. In Pasolini, to the degree there is redemption, redemption lies in the external viewing of a complex tale – not a parable – about an ambitious fragility, or a fragile ambition. In Ward’s work and in Hutchinson’s words, there is redemption. Pain is overcome – indeed redeemed – by creation, by making beauty and life, and, in flashes, love and joy, from the remains of things, bodies, words, feelings, life itself. In Ward’s and Hutchinson’s work, perpetrators are on the other side; Ward’s and Hutchinson’s focus is on fugitiveness and resilience (Hutchinson’s words). In Pasolini, there is nothing fugitive, no one hides (except, perhaps, one time in the movie when Pasolini evades his interviewer’s question about what would remain if Pasolini could magically wave away everything he opposes), apparently nothing is hidden, perpetration is right there in front of you, drawing you in, people are broken down, perpetration itself is broken down. From this forced coherence, I knitted an easy/uneasy synthesis. In the face of suffering, sometimes one wants to shove perpetration up front and say, “fuck you, I don’t care!” Other times, one holds on to beauty, to the possibility of beauty; you want to cry because you cannot but care. And, zooming out, a creation that expresses only one of these impulses will feel flat – just brutal, or just sentimental. I did not find Ward’s, Hutchinson’s, or Ferrara’s work flat. To close, in my way: when I first decided to write about my forced coherence, I didn’t plan to include Jeffrey Gibson’s art and Hélène Cixous’ writing. But, having written thus far, I want to end with Gibson’s resplendent art. That is also life. And Cixous wrote of his dolls, which did not figure in this current New Museum exhibition, “… these were his people, his heritage, his self-portraits. Beautiful dreams, realized, and guarding their secrets.”

*Note: I wrote these words in my running notes. I’m pretty certain all the words and the logic they convey are accurate, but I’m not so sure about the ellipses. In the spring of 2012, I watched The Hunger Games. I was horrified by the story. I hadn’t read the books, though my daughter and nephew and millions of others had. I knew it had a strong female hero and so I expected to like it. But then I found that the core story involves a gladiatorial competition between children, where the winner is the one who survives. The weak, usually the youngest, get picked off first. What mind conceived of this horribly implausible game, I wondered. Never in history, to my knowledge, had any ruler or regime instituted such an entertainment. Yes, children were wantonly killed; yes, people were killed by (adult) gladiators; yes, child soldiers killed and committed atrocities in a “war.” But this pitting of children against children for entertainment made no sense, fit no pattern that I could think of, though it was a compelling story to follow and watch, much like a horror film. It wasn’t implausible in the way a superhero movie with bogus science is implausible, it was implausible because the social premises seemed off.

The only way it made sense was as an allegory. I moved back from the immediate spectacle of bigger children killing smaller children in a lush game world and considered only the most basic scaffolding. The story is set in the country/world of Panem which has twelve districts surrounding the capital. The districts are punished annually for a long-past insurrection by having to give up a child to fight in the Hunger Games. The capital is a beautiful city with wondrous technology, extravagant foods, fascinating clothing. All in all it expresses a climactic moment in human design and artifice. The richer districts are close to the capital and the poorest is far away. Typically, the expectation is that a child from the richer districts, usually one of the older children in the competition, will win (killing or otherwise out-surviving the others). So, with what framing could I find children surviving by killing or out-surviving other children plausible? Looking at the structures of my life, I am close to the centers of power and wealth, not geographically but in class terms. I enjoy some of the ease and luxuries that are increasingly taken for granted, and often further rarified, in those centers. My children have tremendous access to opportunities of various kinds. No, of course, they aren’t like the competitors of The Hunger Games, my mind shies away from the thought, but out there are children, even in the US, who have much less, and further out there are millions of children among the 20 million people who are at risk of starvation, right now in 2017. Our children do not choose these roles. It is as adults that we acquiesce to these structures, with those of us who are closest to the centers of power and privilege acquiescing the most. It’s very difficult not to acquiesce as an individual. The system supports, and is supported by, a web of daily tasks and pleasures. I could pay more taxes. I could give more money to worthy organizations. I could work in public service jobs. I could volunteer. In all these cases, my individual actions can easily be lost or get wrapped into the same-old. It’s not just a case of feeding the twenty million enough that their dead bodies don’t saturate our newsfeeds; and, then, once this crisis is past, we would leave them to a deprivation that is one notch above death. As an allegory, a plausible one it turns out, The Hunger Games helps us see the problem in our own lives, but it doesn’t help us much with a solution. In Collins’ trilogy, Panem’s socio-political structure is maintained with hidden (and not so hidden) violence and trauma, and then is, itself, overturned with extraordinary violence and trauma. We have our own hidden, and not so hidden, violence. But I cannot hope for the extraordinary violence that drove change in Panem. So, in the dull way of ordinary work and long-term trajectories – not just of policies and numbers, but also of relationships and accountability – how do we, in the US, look past one or two elections (2018! 2020!) to a larger, longer-term shift from the inequalities and hidden (and not so hidden) violence of our world? How do we work for this shift across political boundaries? Or can we hope only to hold back the worst extremes? Twenty million people are facing famine now. A few days ago I watched Deadpool. I hadn’t heard of it until my spouse and daughter told me it is the hot, new cult movie.

So here is a quick review. Wry, clever opening credits. Some very good, funny lines. I knew and liked most of the music. And, in general, this is a very well-made, contemporary, white-bro fantasy, racist and sexist despite its sometimes successful attempts at irony. A dream movie for someone who wants to achieve (white) bro-hood through a mass-killing (with a not-so-background fantasy of a beautiful woman who loves you despite your ugliness, and is delighted by your big dick). But I’m writing this review because the movie provoked questions and connections that go well beyond its cool+fantasy appeal, not just to spout my middle-aged feminist judgment. Deadpool is very successful. I gather that many young people, including young women, think this is the best movie they have ever seen. I’m not sure what the young women love about it; my ability to empathize in this context is very, very limited. There is a cool teenage girl, perhaps the coolest character in the movie, but with very limited play. There is also one very tough (white) woman fighter, who in the end is defeated. I didn’t quite understand the plot purpose of an elderly, blind, African-American woman. In the scenes that included her, there were fleeting moments of intimacy and affection, but those moments had little other support in the movie. I very faintly sensed that her role had something to do with pushing the envelope on ironic offensiveness – what could be more aggressively non-PC, and therefore potently ironic, than making an elderly, blind African-American woman the butt of bro jokes? But the jokes in relation to her fell flat, so all that I ended up with was culturally foundational racism, sexism, and age-ism. In these scenes and in general, Deadpool seemed to me an expression of the U.S. zeitgeist, related to, and amplified in, Trump’s successes. My spouse and primary review partner pointed out that the culturally foundational elements of sexism, racism, and age-ism are just that, common to many, if not most, Hollywood productions, and told me that calling them out does not make for interesting commentary because they are to be expected. He pointed out that the success of Deadpool doesn’t come from these elements (though he would probably agree that the kind of success it has achieved would be hard to get without these elements) but rather derives from its layered persiflage of many years of self-important, taking-themselves-too-seriously, overly-earnest super-hero movies. From his perspective, this is what delights audiences who have been fed these movies regularly over the last decade or so. Certainly, Deadpool is substantially more sophisticated in ironic humor and self-reflexivity than the one Fantastic Four movie I’ve seen, and one of the best jokes in Deadpool is about X-Men. I’ve not seen many other movies in this genre so I can’t make a deep comparison. But while I might agree with his point about this reason for Deadpool’s success, I don’t think the foundational racism, sexism, and age-ism, that provide the warp for the movie’s weaving of its contemporary white-bro fantasy, are simply old news. In Deadpool, this foundation is refreshed as the movie connects to, expresses, and is viewed in the context of, a contemporary, mostly-bro, fantasy of recovering American (individualist) greatness, a fantasy that finds its most loud, caricatured, and white version in Trump’s speeches, but which also has more romantic versions that are more widely available, not just for white people and not just for boys and men. The romantic version in Deadpool allows any of us to long for one of the two fantastic social roles it celebrates – the heroic, bro-ish role of someone who survives and succeeds despite a hard life and ugly edges (and who ends up whupping the bad guy); and the immortalized object of the hero’s desire, who is, by the very nature of the role, someone attractive, loyal, and monolithically, uncomplicatedly loving (no doubts, no uncertainty, no resentments, not much discernible subjectivity; dirty socks are just dirty socks outside, waiting to be washed, there are no durable and mutating dirty socks of and in the heart and soul of the beloved). Deadpool rattles through its romantic version of quest for and achievement of individualist greatness, occasionally, very occasionally, with a titillating tenderness, and, beyond the effectiveness of its persiflage, the movie’s success also lies in pulling viewers into glossing some core part of themselves into one (or perhaps both, in some alternating format) of these roles. The Quartz article, “A tip to Americans from an Italian who saw Berlusconi get elected again and again and again,” is not about Deadpool, but it compares Trump and Berlusconi in a way that casts a darkroom’s red light on the U.S. zeitgeist that Deadpool refracts into (more) successful entertainment. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed