|

Dharma and Buddha nature, or layering is a form of propagation

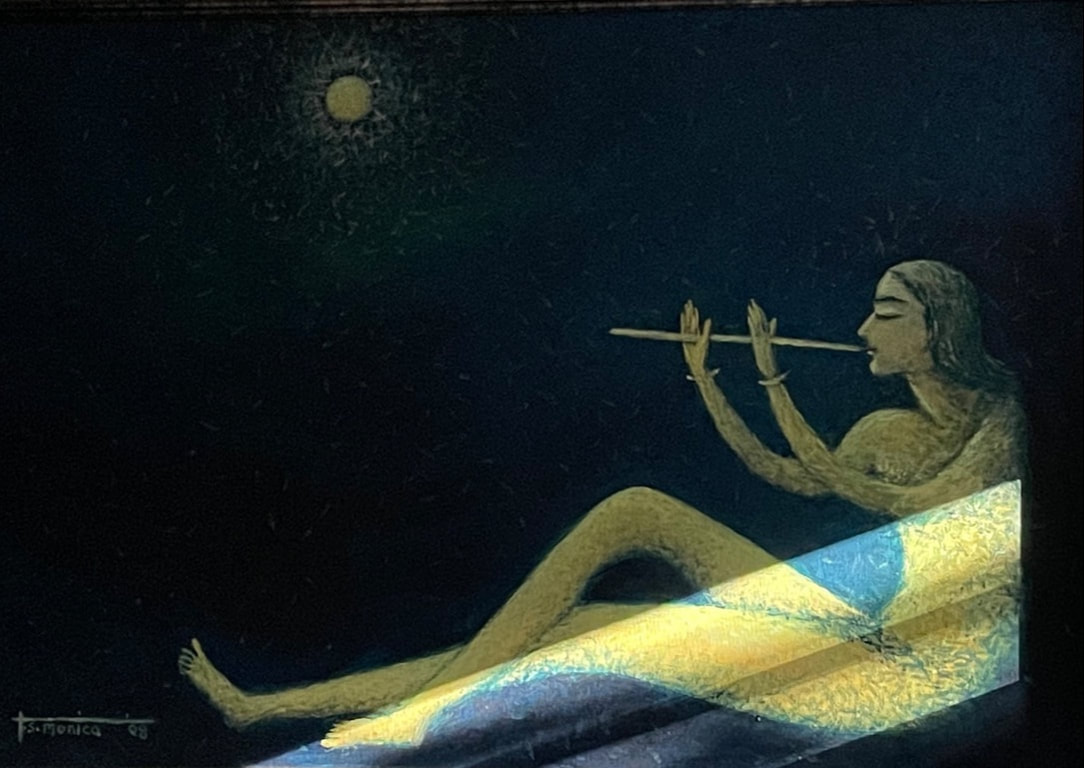

A few weeks ago two different thought clouds clapped against my mind like disparate cymbals, but with no violent residue, no headache. The sounds — the force of each — struck moment after moment of my mind, each confused with the other, and resounded, ringing with joyfully learned, naturally moving polyrhythms. There you have it, the word “nature,” both the ground from which roots draw the substance of life and the material of the roots and tips, indeed the air of respiration. Layering is a form of propagation, Elaine Ng, an artist and my friend taught me. When I told her about how the last months have been, for me, a popping out of a multi-year experience of bewilderment as one life structure after the other changed, some by my choice, some fated by the course of my own and others’ lives, some changes woeful, some joyful, the whole bewildering, I concluded that now, after popping out, I feel like a grown and aged baby. A rooted seedling, she responded. A perfect metaphor I exclaimed, a rooted seedling! I went on to further describe the wending of my aged babyhood. She listened and listened; I’m long-winded. And then she said, I’m revising my metaphor. I looked skeptical. What could be better? And she conjured up and recited a truer metaphor after all. Layering, she said, layering, which is a form of propagation. If you’ve read or heard me speak about my first novel, you’ll know that layering is the ground I walk on, the air I live in, even — to hold no exuberant excess back — the thermoclines I ripple through when diving. (Hmmm, there are no thermoclines in my first novel.) Hunh, I responded curiously and unusually pithily. I said seedling, she said, but you’re a grown plant. A grown plant can get knocked over by something outside itself. It may fall over, be driven to touch the ground. In ideal circumstances, the fallen plant will shoot roots into the ground on which it lies. It’ll draw from the remaining strength of the original plant to grow again with new roots, its tip growing up into new life. After a while this new growth is independently strong. The original plant does not necessarily die, but if you cut it off, the new plant will still live and grow. I’d never known anything like this, so I looked at her with wonder. This is layering, she said, a form of propagation. Really? There are real plants that do this? Is this like the banyan tree? No, I’m not talking about aerial roots like the banyan has, nor about the bowed rooting that is part of the normal growth practice of forsythia and cane plants (mind you, through all of this I was gaping in my mind, if not on my face, an amazed and delighted gaping). I believe, she said, offering the caveat that she is no expert botanist, that “layering” implies that something external forces the plant to the ground. Do you have an example, I asked, a plant I may know? Time, she said. No, she did not say time. Thyme, she said. Thyme! Of course. So what does all of this have to do with dharma or Buddha nature, beyond all of these sharing a space in my mind, a time in my life, that morning of October 21, 2022? Well, let’s start with dharma. I am not referring to what is commonly understood as dharma in Buddhist traditions, but rather a Hindu notion of dharma that I learned as a child and youth. As I absorbed various inflections of “dharma” through stories and philosophical writings, I came to understand it as who one is, living who one is. Your dharma is directly related to who you are, your dharma is to live who you are. This notion is complicated. It’s been pressed into justifying socio-economic stratification in ways which have spilled into brazen constraint and cruelty, as when Hindus have insisted on some version of: you must, you can only, live your caste or lack thereof — your high status, your low status, that’s who you are, that’s your dharma. However, in the stories and philosophical writings I encountered, there are enough examples in which “dharma” is not bound to structural position. I found enough boundary-crossing that I came away with a notion that can expansively hold a complex mess of being human. But then one could ask: do you mean that serial murderers can justify their practice of killing people by saying they are living their dharma? That would suggest a notion so immoral that it has no meaning beyond willful, contingent idiosyncrasy. Technically, yes, a serial murderer could say that. But my dharma, and many of yours too I suspect, includes stopping harm to others, especially what looks like wanton murder, and so we’ll try to find ways or support ways — investigative, judicial, preventive, etc. — to do that. From this perspective community norms and statecraft may be viewed as the collective expression of recurrent and overlapping elements of individual dharmas, including dharma elements related to loving, sharing, seeking well-being, seeking domination, seeking overweening survival-to-immortality, destroying an obstacle, propagation, growth. But this kind of efflorescing, even rampant, dharma sounds very different from Buddhist notions of dharma which modestly propose a way to live with no, or at least less, suffering by giving up the delusion that if you get what you desire you will not suffer. The Buddhist way is taught in a combination of practice and precepts that often enough sound and feel prescriptive. Buddhist understandings of dharma — that I draw from my sporadic chunks of practice with Zen sanghas, and my mostly autodidactic reading and home practice of Zen and Tibetan Buddhist traditions — have both attracted and puzzled me. A mystical, Taoist aspect deeply appeals to me because it seems to hold the length and width of what is knowable and unknowable, but then when I read “when love and hate are both absent everything becomes clear and undisguised,” (Chien-chin Seng-ts’an, Third Zen Patriarch), I make that concise sound again — Hunh? Well, I’m not going to stop loving, so I guess I must focus on not hating, no dualism, so all love, all-all. And from there I’m back to trying to be good, to only love. Efforts to only love mean constantly denying or suppressing parts of myself, or feeling guilty, trying to be better. Not that trying to be better is bad, but denial and suppression invariably come back to bite me. The Buddhist teachers I read foresee that happening and tell me that’s no good either. Ok then, feel nothing, think nothing. That’s not happenin’! Then, on that same day as layering opened up and when I was feeling a nagging conflict of “shoulds” — including the insidious should not-should — around a personal dilemma, I read some pages of Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind for the nth time: “When there is no gaining idea in what you do, then you do something. … It is just you, yourself, nothing special.” Bingo! It’s my Hindu notion of dharma! Buddha nature is living who you are. Nothing special. So maybe greedy, conflicted, unhappy is who I am, so nothing further to be done, you might say to me. Maybe, I would respond. I can’t tell you who you are. I could tell you what I experience but that may or may not be interesting or helpful to you. But if you want to feel differently, be more comfortable in yourself, I do find the Buddhist path to the root of your suffering a helpful practice and exploration. Importantly it’s a living that has no end apart from itself; it both has a goal and no goal. From this perspective, fulfillment is not a levitating cushion of certainty. I’ve found the path laid out by Chogyam Trungpa, particularly in his teachings in The Truth of Suffering, helpful. His detailed description of the path of the Hinayana way to liberation from suffering starts annoyingly prescriptive and ends with illumination of a potential passage to clarity about who one is. Parenthetically, Trungpa’s teachings seem to contrast oddly with accounts of his un-Buddhist sounding lifestyle that apparently included womanizing and alcoholism. These may seem logically inconsistent, even hypocritical, but they are not inconsistent in the body, mind, and emotions of a human. This way of looking at it is not about justification, it’s about seeing all the parts.* Nothing special. Trungpa’s teachings, along with the backdrop of his life, are dramatically different from Suzuki’s austere expressions of his Mahayana way, but they converge for me on an understanding of life, of Buddha nature. This Buddha nature is nothing special; we all have it, we can all uncover it, and it’s not all one thing. I realize that many committed Buddhists may find what I’ve written here inaccurate or misleading. To them and to you, my dear reader, I say: find your way. This is where I am on my meandering way — sometimes dancing along, sometimes staggering with too much, sometimes taking the long way deliberately, sometimes levitating on that cushion of delusional certainty, sometimes the cushion collapses and I fall to the ground, and then LAYERING! Among the recent life changes that bewildered me, my mother passed away from pancreatic cancer. She was my remaining parent and caring for her in her last months turned my experience of life from living and death to dying and alive. Caring for her I became corporeally aware of impermanence, of how life falls away from body and consciousness even as we live as we are now. So here I am: new growth, energetically grounded in impermanence, uncertainty, and incompleteness. Alive. I can only live who I am, die who I am. Nothing special. * Is it too much, too extravagant, pushing limits too far to suggest that you read Rita Dove’s brilliant, lovely poem “The Regency Fete” in this context? AND I struggle with how this notion of dharma or Buddha nature can become a refuge, a delusion in itself, whether on the cushion or debauched like the Prince Regent or colluding, by commission or omission, in the collective injustices of one set of people upon another. Where is dharma there? Whose dharma? If I have the answer in one dimension, I don’t in another. Uncertainty, incompleteness, imperfection, nothing special. More meandering through dharma, vegetation, changing light, inconclusive living A couple of weeks after the above piece was first drafted, I looked out of my window and gazed at a tree — mostly yellow, some green still, a few bare twigs — glowing in the morning sunlight, and mused: if I am the tree, I can’t be the sun. But I can enjoy that light, let it warm me, feed me, enrich my living. And I can glow and be beautiful just as I am, making the beauty of my spread and my colors, just as I am. And perhaps someone like me will look at me and see that spread, those colors, my glow. I may not know it, I may never know that Meenakshi watched my leaves grow yellow and fall in yellow showers and loved me and felt her life enriched by me. It’s just the way I am, I live, until I don’t. These sentiments, projected onto and drawn from the tree and the sunlight, became conscious as I decided to continue reading Andrey Tarkovsky’s lovely Sculpting in Time. But first I dipped back into Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind and found myself reading what seemed to me exactly the description of my vegetative life that morning (though perhaps not quite obvious in this telling): “When you know everything, you are like a dark sky. Sometimes a flashing will come through the dark sky. After it passes, you forget about it, and there is nothing left but the dark sky. The sky is never surprised when all of a sudden a thunderbolt breaks through. And when the lightning does flash, a wonderful sight may be seen. When we have emptiness we are always prepared for watching the flashing…. If you want to appreciate something fully, you should forget yourself. You should accept it like lightning flashing in the utter darkness of the sky.” [Meenakshi’s added note: forget the should as well.] Of course that vegetative sharing of life with the tree came in the morning, in a time of glory and reflection. But then, that same evening, as I was lower, duller, I looked at that same tree that now, like me, felt night fall heavily. Another dog had pooped, another man had peed. A paper cup and a plastic bag lay in the speckled mud of the tree bed. If I were the tree I’d be wondering: where will my seeds go? (This tree has lovely large, dark clumps of seed pods.) Why do I even bother morning after morning, night after night? So this is living, it’s not all glory and reflection. I’m also reading Moby Dick. Melville names submission and endurance as womanly virtues, in one of his rare references to the female of a species; most such references offer soft contrasts to the looming, flailing masculinity of the more obviously active characters, indeed of the exploration itself. So, does the tree submit and endure? Is that its action and heroism? Inconclusion

0 Comments

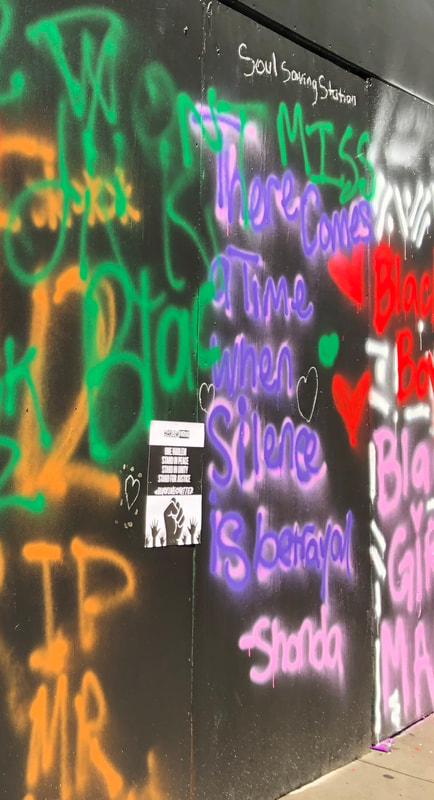

Age may have something to do with it, but I’m not sure. I was safe from March 2020, even before that, and I’m safe enough now. I was healthy enough to start with, and had enough money. Two grocery stores near me were open, a friend sent me a mask when I needed one, my daughter sent me more, I bought a few, I had lots of Zicam, ibuprofen, and Vitamin C, and I live close to the river, which means I can walk by the water. I had my phone, and FaceTime and Zoom. For some months, the only real people I saw were on the streets, in Duane Reade, and in my two grocery stores. People died, many people died in New York City; I didn’t know any of them. In May I saw a morgue truck a twenty-five minute walk from my home. Then one of the grocery stores shut down, the one I favored; it had been struggling already. I already had a practice of drawing pleasure from small evidence of life or shape: a sparrow; the magic of a male cardinal, his insistent courtship; the loud cacophony of birds in the morning; the small bumps on branches outside my window that grew and burst into fragile green then darkened to heaviness; the early yellow of some hasty fellows, some as early as June; the fall; the winter again. But now I saw and felt more of these, and more than these. I gazed at the shadow of the locked gate on my fire-escape window. I watched the light of the late gibbous moon swell until it was full through the gingko in the backyard. The plants silhouetted against late light in neighbors’ windows became my friends in the night. A trumpeter played and played and played until two or later in the night; then he was gone and the lights stayed off in those windows. I watched mourning doves squat the abandoned blue jays’ nest outside my window, lay eggs, share brooding duty, then one dove disappeared, the other tried, gave up, and the eggs dried to shells that caught the wind and blew away; in grief and greed I prised the nest away and tossed it to use the fire escape for my solitary Covid wine. One May evening, that same May when I saw the morgue truck, when I went back in to replenish my glass of wine, I found G from downstairs with two policemen at my metal-sheeted door. Someone had heard a shot. No, it wasn’t in my apartment, not even in my building; I hadn’t heard the shot, I never heard any more about it. Through all of this my beloved solitude fell in upon itself, and I wept my losses of the past and the desperation and afflictions – the rising illness, deaths, helplessness in my city – of the present. Then the woman with the unleashed dog called the police on the birder who protested, and then George Floyd was murdered. Black Lives Matter, the weight of history, the pain, but now we had a cause, a bigger-we though not all-we.* And Trump amazed me everyday. This small man played the role of incoherence, instability, falseness, indeed the honesty of falseness, it just is he’d say, usually loudly, this is who I am, this is life. We had to get him out. It’s not that I dream of goodness, not that much anymore. The world is breaking and even we in the United States are sliding into horror. Oh, we already had horrors. Horrors – most horribly of our making, believing ourselves good, or we just said that – have accompanied us throughout. Some of us were rich enough, some white enough, though white by itself was not always enough, to choose not to see, not to hear, not to smell, not to feel. Through all of this I had joy as well: the river I mentioned, the spring, the summer; walking miles and miles to meet a friend, each weighed-down, delighted, to see the other, although we couldn’t touch. Later we picnicked in a city meadow, blankets six feet apart, with cocktails that were peddled by hurrying men, $10 for a mojito or a margarita in a small plastic bottle. What joy! Perhaps most dear, my daughter, graduating on Zoom, came to live in NYC with her partner. And then, in September, my children, my friends – Covid be damned – managed to make my sixtieth birthday one of my best ever. In the fall, I had Diwali dinner with some of these beloveds, and in that fraught and hopeful winter, Christmas dinner right as Covid knocked closer than ever before. An intrepid friend went to visit her parents in India. Time to visit my mother, I decided, and so I followed. We’d talked everyday, my mother – then 88, now 89 – and I. We’d been alone, more or less alone, ten thousand miles apart. I flew, double-masked with NYC caution, quarantined for a week then had a test, negative of course, so then why the intense relief? Paranoid Meenakshi with her old mother, paranoid old Meenakshi from NYC. I loved the light and warmth of Goa, the food. I learned again the joys and irritations of living with someone. I touched the passing of time in my life and the lives of loved ones there. Old friends, new friends. Cases started going up, sneaky small numbers with their sneaky high rates of increase. Most people there, and elsewhere, did not worry; I worried, but not a lot, not enough. And I did not write, I did not write, I did not write. I had not written in a while and that did not change. Instead, I sat heavily or jumped. Time was passing and with it my relevance it seemed. Two months in Goa, during which I got my mother vaccinated and old-enough me along with her, and “wonder of wonders, miracle of miracles” – yup, I sang that over and over in my Kolkata Catholic high school’s production of Fiddler on the Roof more than forty years ago – I heard that I-Park had a place for me in the second session of their reopening residency program. I-Park, the name, the residency, became a time beacon, a stable place in what felt largely like a life of uncertainty and irrelevance, though reasonably comfortable and safe. Meanwhile, cases were still going up, in India, in Goa, which was worrying but not alarming yet. All of it worrying enough, though, that stress built as I prepared to leave and helped prepare my mother to return to her north Indian home. Luxury would help I thought, so I blew a wad at upgrading which, on Qatar Airways, meant a little room of my own, cotton pajamas, and good wine. On that plane, a 14-hour flight, I wrote more than I had in months. I felt only relief, not even guilty at feeling no guilt. NYC was getting vaccinated! I returned hopeful. I’d crossed watersheds, crossed something, crossed over, I thought. I was ready to start anew, rebuild life with my loved ones, build community with new friends, new loved ones, get politically active again to build the world I want to live in, or at least to heave against horrors of the past, present, and future. And of course to write again. And now perhaps to find loving eyes for my writing, people who would keep reading my words, their bodies suffused with “aha, I know this, it was always there.” But my hope turned out to be only exhaustion – from what, you safe and upgraded woman?! Even my upbraiding of myself was exhausted. I didn’t write. I worked through practical tasks, continued to be warmed by those who love me and whom I love, put one dragging foot after the other in the sand of this new shore, was it even a new shore? India sprung into disaster, death, death, death, burning. And I started hearing from friends and relatives that a loved one, often more than one, had fallen ill. Some died. My mother stayed physically well but fearful and lonely. I stayed physically well in increasingly vaccinated, open, and green NYC, and I felt exhausted and lonely. I met and talked to friends and family. These conversations reminded me that I was well-loved and not alone, but it was as if the months of my Covid confinement – of the body certainly, but also of the fearful, uncertain mind – had led to a separation of the physical (or external?) me – “I’m ok, actually I’m well” – from some other me held in the same cells of that same body – “I’m exhausted, uncertain, alone, so what.” I didn’t write. Through all this there was joy as well. That river (the Hudson!). Spring again. Noisy adolescent birds. Sitting back with pleasure, though still outside, at a favorite restaurant. My older child came to visit for two weeks, what joy to have both my children with me! Friends continued to love me and be loved. I even met two more men I liked well enough to meet again. If you’ve seen or heard me in this time, I look well, I sound strong, I laugh quite a lot, and all of that is truly me as well. I-Park remained a beacon, straight ahead; not an Avalon or Shangri-La or paradise of any sort, just a place and time of calm in which I would be still and deep, and write. I rushed to finish as much as I could of my busy practical work. Person after person who heard about the residency wished me well. And so I came to I-Park, masked in an ordinary way, in an ordinary crowded train, and found a place that no one deserves, so I draped myself with this time and place as a gift, a module of life and living that is not willed, that is out of my control. In a way it’s like an upside down Covid. It’s beautiful here, with green, green, green, a pond, and site-specific ephemeral art on wooded paths. A path runs through Thanatapolis, city of death. Prediction, or prophesy, simply means the stating of what happens: it’s happened before and will happen again.

I’m here. I’m writing this in my studio. I’ve walked many of the trails but not all. I’ve eaten lots of wild blackberries and I’ve fallen in love with wild fungi all over again. I have snake envy – I haven’t seen a rat snake yet, others have – but I’ve seen six turkey children walking single file, with a parent leading and a parent watching the rear. The summer in the Northeast is humid, so damp meets every sense and movement. And summer insects dive into my ear, not nice. The other artists here – two visual artists, an architect, two composers – are fascinating and about the ages of my children. Our difference in ages should not be relevant, but, inevitably, it is, as we chat in a present that moves malleably and sometimes awkwardly between our incommensurate has-beens and will-bes, with varying curiosity, distance, learning, and perhaps even irritation. All fully vaccinated, we agreed to be a pod and moved from personal fear of Covid to personal fear of Lyme disease. Our artist group seems to have adopted ticks as our fear mascot. I finished reading a manuscript I was scheduled to send to a bookmaker in Berlin who is working with me to create an artwork edition of my first novel. Conceptualizing the design and working with him has been a creative adventure in its own right but it doesn’t consume and stimulate me the same way writing can. I still was not writing. One of the other resident artists pulled the Hanged One tarot card for me and that led me to let something go. Somewhere in that swirling, giving up was giving up expectation and failure. I’m small. Start small. Was this what writer’s block is? I haven’t had writer’s block before this, at least not enough to be named as such. Writer’s block or not, my state seems larger (though I am small!) than my writing. I’m stagnant between the course of my pre-Covid life with its logics, joys, fractures, and morphoses; and now – is it a post-covid life? – with everything thrown into question, a state of dreamlike precarity, with an insistent will to joy, but a seductive fatalism in one corner that sometimes looks like a comfortable resting place, and sometimes is a narrow, romantic, nihilistic acquiescence to death, to nothing. I’m well in the second half of my life and Covid amplified what older people experience more commonly, I think, than younger people – mortality. Death threatens meaning. Forget the course of it, I say. Treat this state, I instruct myself, as a beginning on a new plane, no more nor less than the last, but different. I don’t have to know what this blog post will open as my first new writing of any length and significance since February of 2021, this dodgy time of post-Covid-still-Covid. It may not open anything. It may just be a whistling not-yet-a-tune that knits once more my cut-off, cut-down selves that are held within my safe-enough and healthy-enough body; though sometimes I think they float around me in words or feelings, all in a complex world of pain, joy, horror, love given and received, love walking away, walking away with love (to quote Abbey Lincoln). The will to live, the will to love, the will to death, not only once, not necessarily in that order, haphazardly out of our control. Deflated, defeated, laughing, loving. Writing. Hear me: I am alive, to be me, to do this writing now, committed to living which extends

Traditionally, the Moirae, more commonly known as the Fates, were imagined as old. They spun the stories of the world to come, each story fresh, even if not new. Today, when, grey-haired, I begin my official writing career, I find myself wondering how someone will describe the stories I spin. If I were a young author, the phrase “fresh, young voice” would spill out easily, if tritely. They, whoever they are, can’t use “young” with me, so perhaps they can say “fresh, new voice” – too glib, and redundant.

I hope they wouldn’t say “tired, old voice” though “tired” is an underrated quality. If it didn’t have the grey tinge it does in today’s cultures of positive energy, I would claim it proudly. Tired means worked, and worked means stories can come from all those elements of my being that have been active – my fingers, my feet, my womb, my brain, the neurons in my gut, the ineffables of my heart. But I am too afraid to call my stories “tired, old stories,” and I don’t want them to either, because they won’t understand “tired” as I do (the “tired” of my mother who woke up at four, you know the story; the “tired” of the man who cycles 10 miles (to work) before dawn and (home) at dusk each day, which you think you know but most of you, most of us, don’t really, not in the degeneration of our flesh, the worry in our gut). So, now, when I google Moirae, I find many drawings of prepubescent spinners. And, indeed, they too spin the stories of the world to come, each story fresh, even if not new. Moirae are the form of original storytelling, the story constructing the Moira, whatever her age (and gender?). This thought leads me to a happy new phrase, “fresh, old voice” that describes the Moirae of old and the parts of their tattered mantles I want to wrap around my name before it spouts its stories at you. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed