|

Madre and desmadre

I very recently became aware of a Spanish word desmadre, first spoken more generally in my presence and then directly to me by a group of magnificent women in the centre of San Diego. I was told desmadre means ruckus. The way I heard them use the word, it sounded like John Lewis’s “good trouble.” I thought it was two words. Of mothers? No, no, I was told, one word, meaning ruckus. The word intrigued me. Does it have something to do with madre? Well, of course it has something to do with madre, I found. It comes from a root of separation from the mother. Disintegration. Chaos. And now good trouble. In my three works of fiction, all the main characters are women: two wandering mothers, one grandmother, many daughters. My first and third work are about separation from the mother, in one case chosen by the mother, in the other not chosen by the mother. I wanted to close these books, close the stories, go from heimlich to unheimlich to heimlich -- the formula for a good novel I was glibly instructed by a literary agent with unliterary tastes — but the characters are broken are broken, whole only in the luminescence of the world in which they live, loved and loving. Earlier this year I presented the artwork edition of my first novel, Night Heron, in Berlin. My daughter introduced me, moderated the presentation and asked me how I came to write this novel about a visual artist who leaves her son for no very good reason, neither heroic ambition nor poor traumatic past. For the first time in all my stumbling, convoluted speaking about this novel, I spoke about the motivating ambition for this story. It was simple and too ambitiously silly to be spoken of before this, but there in Berlin, speaking to my daughter and a group of mostly artists and writers, I said I wanted to create a female Stephen Dedalus, as in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which I had loved as a young woman. I wanted a woman to step out as vividly: the language, yes, but also that stepping out. I found no Dedalus. There was no easy Dedalus, no female derivative who felt remotely real or interesting. My own life at the time — a mother of young children — pushed me to the not-Dedalus figure of a mother of a young son, and then she leaves her son, which is experienced as desmadre by all readers, disturbingly and uncomfortably so for most, satisfyingly provocative in a melancholy way for some. Art and writing has often propelled or reflected desmadre, traditionally in most parts of the world in the voices and through the agonies of men, often men with, or aligned with, more power (though they could and often did write about men of less power and even women). In the last couple of centuries that has changed. This change has become more rapid in the last sixty years or so as women and traditionally less powerful men — less powerful at least in the context of our long modern era of military gunpowder, industrialization, colonization, and rampant capitalism — have explored what it means to articulate main characters from their own experience of work and living in crowded interior and exterior worlds. Which brings me to an early stimulus for this blog post. A few days ago, biographyof.red, an extraordinarily delightful Instagram account that evidently springs from Anne Carson’s work and posts mostly poetry, posted an excerpt from Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. The excerpt, in turn, quotes Henri Bachelin on the conjuring of myth - involving “tragic cataclysms” of the past, and ends of times — around winter hearths. Evidently this conjuring comes from men, most definitely not old women who tell “fairytales.” Bachelard’s and Bachelin’s lovely words inscribe the space in which old masculinist myths can loom. Their words projected to me a willfully blind desire for understanding that penetrates “the end,” that grandly foresees its own tragic failure. I refused this space and asked myself, what larger space do I make, what poetics if life is the hurling of oneself — whether slowly, grandly, or awkwardly — against the hard transparency of end? What poetics, what space for people living splintered lives — loving, working, laughing, living — and expiring despite themselves, where narratives of yawning pasts and distant ends are often unheeded? Yes, yes, I know, Shakespeare, Dickens, the novel. And, yes, how does this relate to madre and desmadre, apart from the obvious gender stuff. Well, yes, the obvious gender stuff is key. Madre, a trope for connection, with all its connotation of home, gathering, shared food, shared corporeality, cooking, fire, transformation, sometimes even hearth. Complaints, shush, small tales, snoring, reaching into “forces and signs” by women and men. Desmadre, inside and outside. Inside and outside bodies, inside and outside that gathering at the hearth, inside and outside the home, heimlich always roughly pixilated, parts spinning into unheimlich, unheimlich pressed into new forms of homeliness by personal and collective intimacies. From trope to subject, madre to desmadre, women and the historically less powerful are saying we will occupy this hearth, we will make the space under crossing highways a hearth, we will make it a space for life, for gathering, for drought-resistant plants, for art that exclaims “we are here!”, and here encompasses the beauty and pain of our pasts, the struggles and dancing of our present, and our shared future of children, life, and death, all of that! I didn’t know how this blog post would spin out. It is still spinning within, tilting into aliveness, spilling into uncertainty. Madre and desmadre are mythical figures of worlds that have long been binary-gendered. As binary gender dissolves into two figures in a much larger flow, or if gestation becomes incubation in genderless machinery and separation becomes connection to a human, will madre — traditionally female, one of a binary, bloody and corporeal — change? I don’t know. The best I can do for now is to observe that the binary was always only a device, a tool for organizing rhetoric and meaning. The non-binary has always been available, residing in both vast madre and desmadre. Reflecting on the mothers in my fiction and the space-making event alluded to above, madre also seems to connote separation and desmadre also connotes connection, gathering.

0 Comments

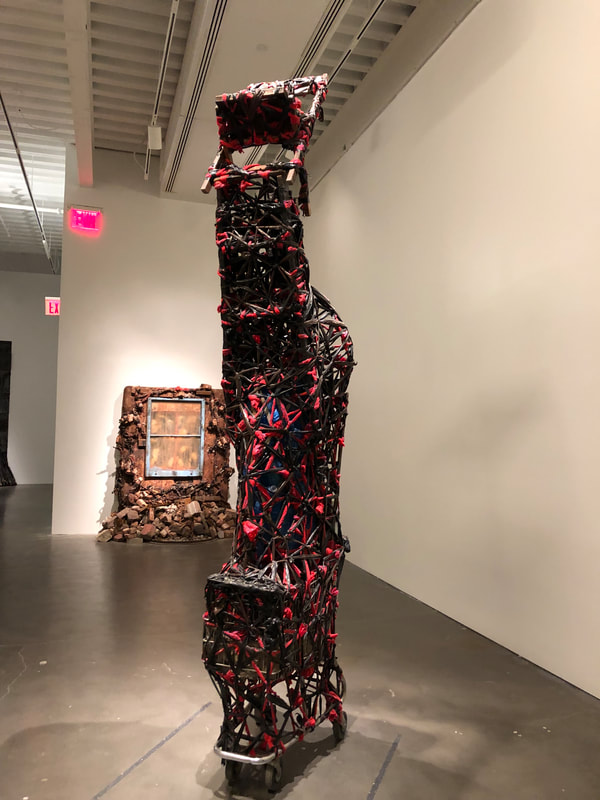

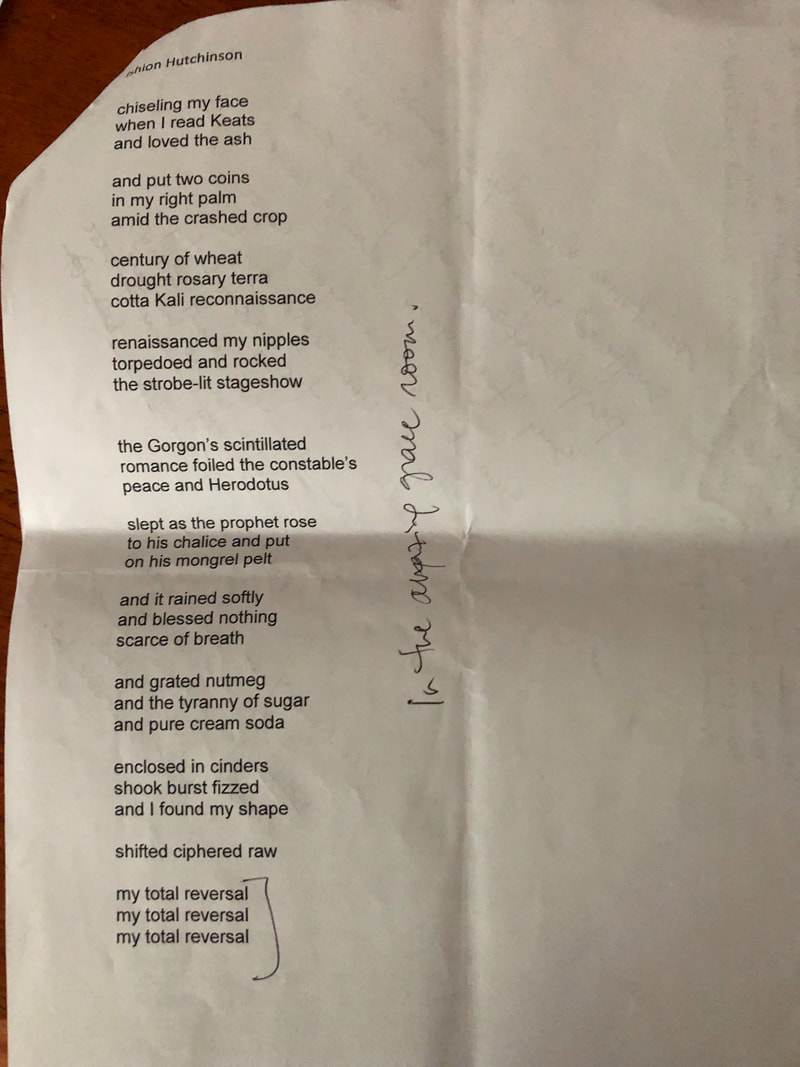

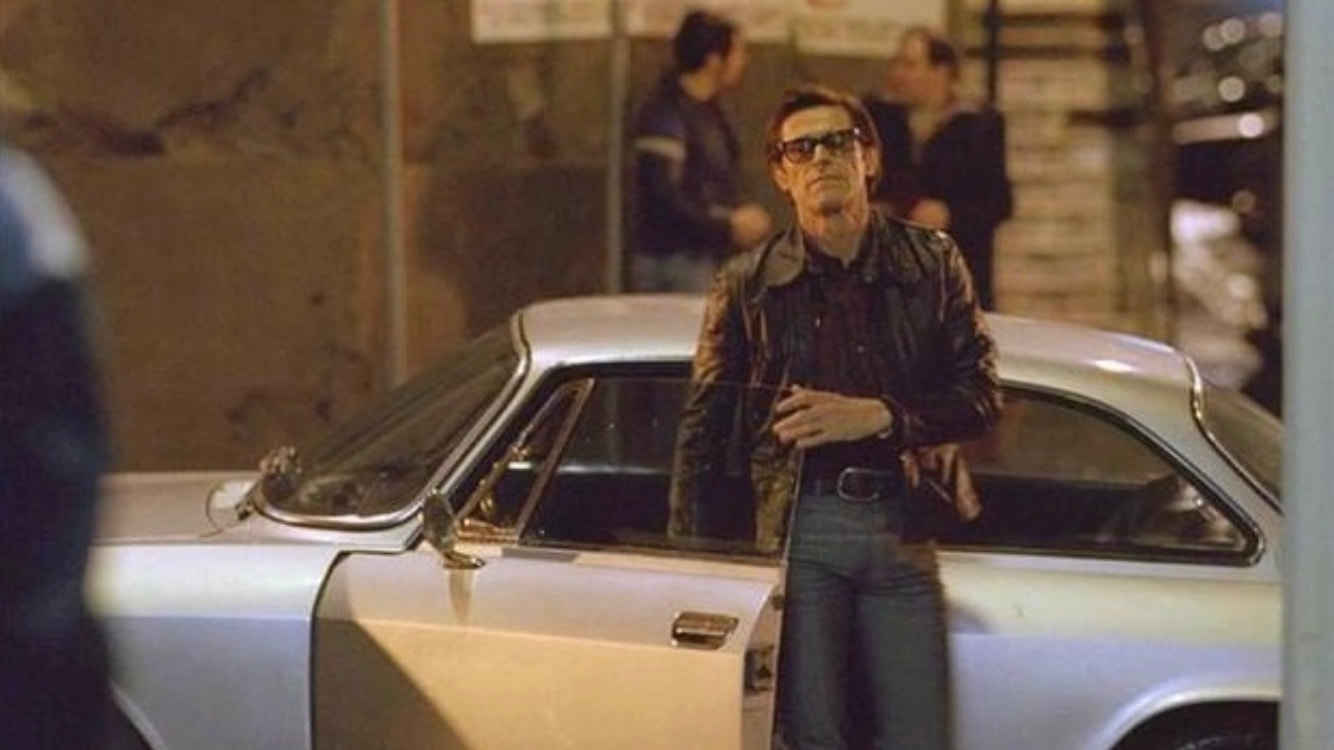

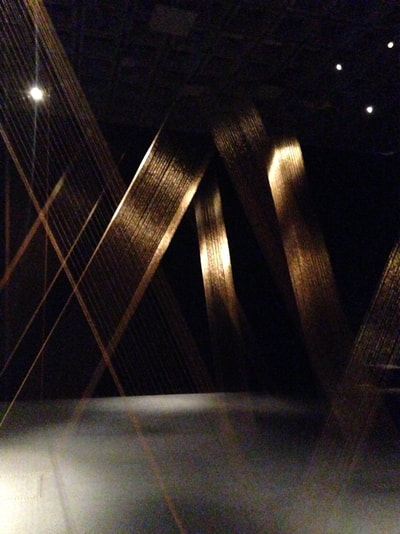

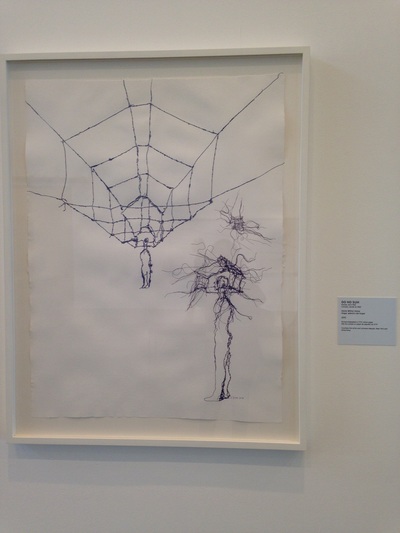

(Spoiler alert re the movie Pasolini) The sequence of Nari Ward, Ishion Hutchinson, and Pasolini just happened; there was no plan on my part. Nari Ward and Ishion Hutchinson were paired by the New Museum. Not unexpectedly, they were a good pair, or rather I found Hutchinson’s response to Ward’s art provided something like a blended glass, part mirror, part filter. More about that in a bit. I added Pasolini because I wanted to use my Metrograph membership; I could walk to The Metrograph from The New Museum, and Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini was playing at the right time for me to move in this way through the city. Interestingly, going to Pasolini also became the right movement for a kind of intellectual and emotional trajectory. Though this is often the case as we knit the past into some kind of coherence, in this case I struggled with making the sequence coherent, then forced a coherence, and then was struck by what came of and from the forced coherence. I went to The New Museum for the first time about two weeks ago because a friend wanted to go there and I’ve wanted to go there for a long time. We started on the top floor with Jeffrey Gibson’s kaleidoscopic work and I passed through his work, loving the color and the immanence of movement. Later, I passed through Hélène Cixous’ odd, insightful, and romantic essay on Gibson’s work. “A dislocation is at work,” she wrote. Then we went down three floors of Ward’s large installations and smaller, more compact, art in the exhibition called “We the People.” The making of art from found objects is not new but the poignancy of this exhibition lay in the bend between the mourning of pain and history, and the fertility and beauty of, somehow, life. I had not heard of Nari Ward before this and got a little uncomfortable when I heard that he is a Harlem-based artist and his art connects directly to dispossession, not only of the past, but directly in the effects of gentrification in the present. I moved into West Harlem in June 2018, an innocuous, older-ing, and brown woman. I belong here, and I don’t. I had noticed, when checking out the museum before I went there with my friend, that Ishion Hutchinson was going to do a gallery talk on Nari Ward’s work. When I asked if there were still tickets available for that gallery talk, I was told there were. I was stunned. I guess this is NYC. I said, if you don’t think they’ll sell out while we, my friend and I, go through the exhibitions, I’ll wait to see Nari Ward’s work before buying a ticket for Hutchinson’s gallery talk. They assured me there would still be places, and there were, and once we’d walked through and down all the floors, I bought a ticket for the talk. So, on Thursday, May 16, my hair freshly colored, I went back to The New Museum, and waited for Ishion Hutchinson’s gallery talk. Ishion Hutchinson, like Nari Ward, is Jamaican-diaspora African-American. He is a poet I much admire. He took us, a group of about fifteen people, through parts of “We the People,” with eloquence, diffidence, clarity, and kindness. He took us – none of us belonging to the African diaspora, though all of us share fraught histories with Nari Ward and him – through touching what ‘fugitive’ can mean in history, selfhood and art; through hearing the grandness of aspiration while living in “material fetishes of failed utopias;” through sensing, distantly – in our case, each of us, perhaps with some guilt, or shame, or desire – “an old resilience which is part of [Hutchinson’s] heritage.” He told us about the abeng, and made its sound with his breath, his throat, and his mouth – this was a generosity of sound, not just a performance or lecture – and related it to the artwork called Savior. The abeng, he told us, makes the sound of the fugitive. He lost his voice briefly after making that sound. He stood in front of the two pieces called Breathing Panel and, at the end of his prose response to the artwork, repeated, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe….” In that brightly-lit gallery, with chattering, whistling sounds from an adjoining artwork, with only one other African-American, a gallery attendant, in view, with one other gallery attendant who looked Latino, and me, a class- (and caste-) privileged South Asian-American, with everyone else phenotypically white, mostly women across a range of ages, I wondered who couldn’t breathe now, why couldn’t they breathe. Who is breathing? For how long? Then he took us to the large, dark room in which Amazing Grace was installed; “a womb, a slave ship, an ark,” he called it at the beginning and towards the end. He walked us, two-by-two and holding hands, through the stroller-ship-womb. He read his poem Sprawl and repeated “my total reversal” – the last three lines of the poem – more than three times. And then we were done. And I got him to sign my copy of House of Lords and Commons which he not just signed, but also inscribed with “a small, drifting raft” for me. I walked out into the sunny afternoon, exchanged cheery words with one of the outside guards, walked through Chinatown, got a text message from my daughters in which they laughed at my ‘culture-vulture’ day, got to The Metrograph, and bought a ticket to see Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini. On Instagram, I posted some pictures and wrote: it’s hard to call walking through Nari Ward’s work at The New Museum a pleasure, but perhaps one can call it a tenderness, an amazement at how beauty can come alongside, and from, ugliness and sorrow while underlying cruelty and pain remain cruelty and pain. Pasolini starts, if not right away then very early on, with explicit, aggressive, unlovely sodomizing of two submissive young women. With Pasolini, I seemed far from the fugitive grief and anger and grace of Ward’s work and Hutchinson’s words. There was abject or abjectify-ing sex, followed by ordinary domesticity and interesting, but cold, words. “Narrative art is dead,” Pasolini told us, “we are in mourning.” “Mine is not a tale, it is a parable,” he said, “I am a form, the knowledge of which is an illusion.” To Pasolini, it appears, I, Meenakshi, am a moralist, who neither seizes the right to scandalize nor feels pleasure from being scandalized. About a third through the movie, I wrote in my running notes: so far there is very little that one might call kindness, or love, or tenderness. I watched more sex -- this time apparently not abject or abjectifying, more a kind of revolutionary procreation in a reversal of desire -- between beautiful people, with a raucous audience within the film, and us, a quiet audience outside the film, with our own arousals and withdrawals. Pasolini sees his work as a revolution. “I’m asking you to look around,” he says, “and see the tragedy… … starting with universal education … which leads us to want … and not stop short of murder…. … an appalling tradition that is based on this idea of possessing and destroying.” * The tenderness came at the end of the movie, when Pasolini is beaten to death on an industrial beach and the movie closes with a “clip” from a made-up movie based on Pasolini’s last work-in-progress. In the clip, Epifanio, an older-ing man, and his young companion are trying to get to Paradise and Epifanio can’t go on, so the young man says, “The end doesn’t exist. So we just wait. Something will happen.” Obvious shades of Godot, but owned here in its own terms, with its own peculiar pathos. In the end, the tenderness comes from the unabashed living of, and looking at, life with all its ugliness, its earthiness, its longings, its sensuousness, its beauty of form and light and shadow, its flaws, and just life. In general, I prefer to look at, sense, and join joy and tenderness of a different kind, but I did feel the tenderness at the end of this movie. Then started the struggle of knitting the coherence of my past. In my head, I stared at the obvious challenges of colonialism, racialism, the cruelty and survival of color lines of history, simplistically pitted against normative sexualization, scandalous desire, the intense ambivalence – intimacy and violence – of sex, and the cruelty and survival of power lines of history and didn’t get far, actually didn’t get anywhere, so retreated to higher abstractions. This is what I found. In Pasolini, there is no redemption, no desire for redemption. There is (only?) a wild grasping for freedom outside a cruel system that must be broken. In Pasolini, to the degree there is redemption, redemption lies in the external viewing of a complex tale – not a parable – about an ambitious fragility, or a fragile ambition. In Ward’s work and in Hutchinson’s words, there is redemption. Pain is overcome – indeed redeemed – by creation, by making beauty and life, and, in flashes, love and joy, from the remains of things, bodies, words, feelings, life itself. In Ward’s and Hutchinson’s work, perpetrators are on the other side; Ward’s and Hutchinson’s focus is on fugitiveness and resilience (Hutchinson’s words). In Pasolini, there is nothing fugitive, no one hides (except, perhaps, one time in the movie when Pasolini evades his interviewer’s question about what would remain if Pasolini could magically wave away everything he opposes), apparently nothing is hidden, perpetration is right there in front of you, drawing you in, people are broken down, perpetration itself is broken down. From this forced coherence, I knitted an easy/uneasy synthesis. In the face of suffering, sometimes one wants to shove perpetration up front and say, “fuck you, I don’t care!” Other times, one holds on to beauty, to the possibility of beauty; you want to cry because you cannot but care. And, zooming out, a creation that expresses only one of these impulses will feel flat – just brutal, or just sentimental. I did not find Ward’s, Hutchinson’s, or Ferrara’s work flat. To close, in my way: when I first decided to write about my forced coherence, I didn’t plan to include Jeffrey Gibson’s art and Hélène Cixous’ writing. But, having written thus far, I want to end with Gibson’s resplendent art. That is also life. And Cixous wrote of his dolls, which did not figure in this current New Museum exhibition, “… these were his people, his heritage, his self-portraits. Beautiful dreams, realized, and guarding their secrets.”

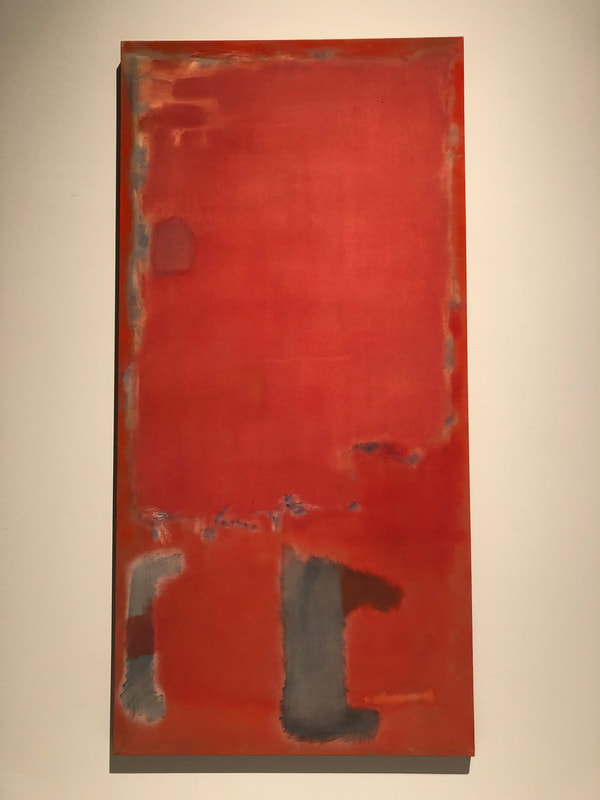

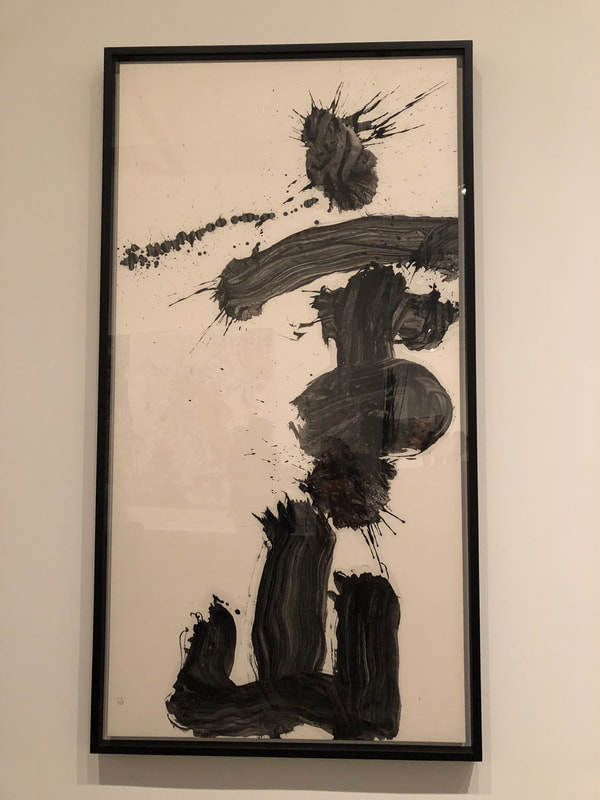

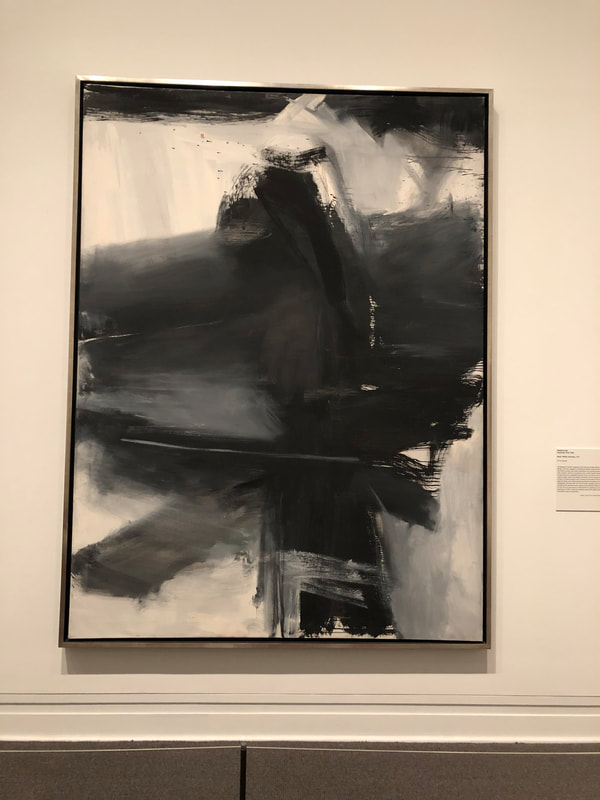

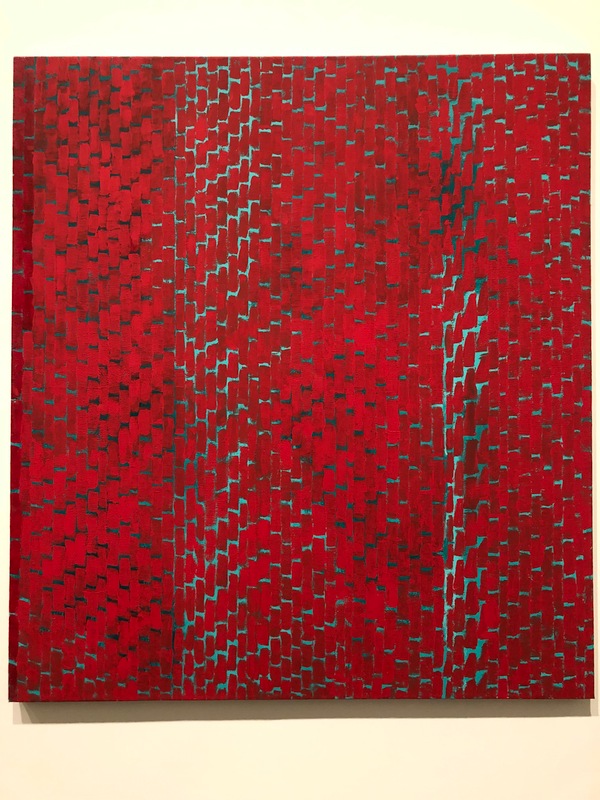

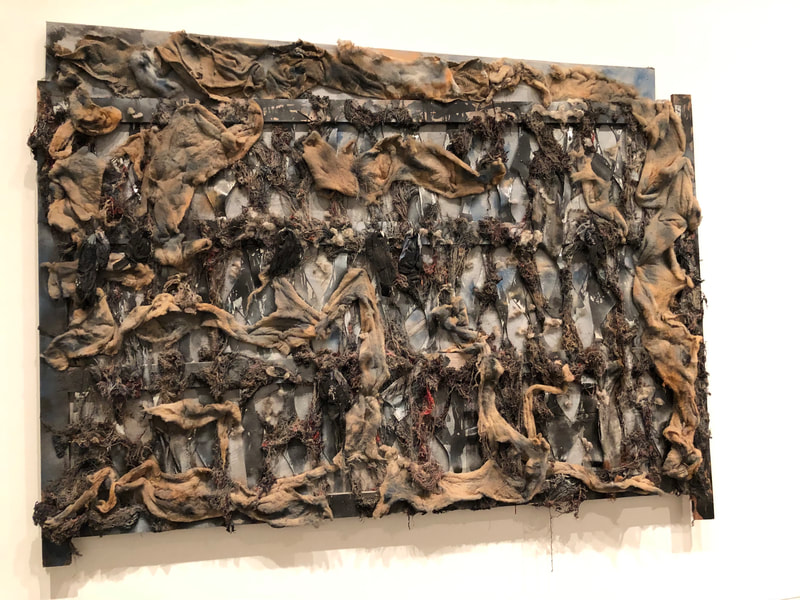

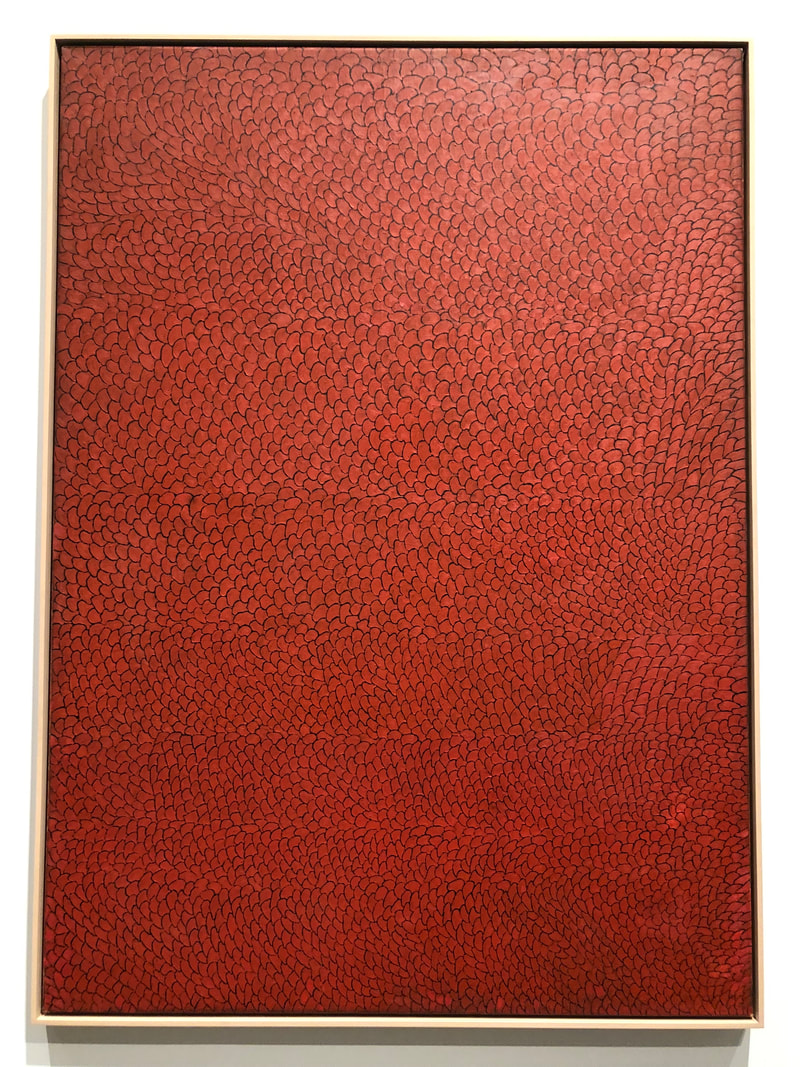

*Note: I wrote these words in my running notes. I’m pretty certain all the words and the logic they convey are accurate, but I’m not so sure about the ellipses. The title of Zora Neale Hurston’s most famous book comes from the sentence: “They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” This is an extraordinary sentence in a book full of extraordinary sentences. I read the book weeks after walking, for the first time, through the Epic Abstraction exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In that first encounter with Epic Abstraction, I was astonishingly moved. I don’t cry in public, usually, so I didn’t cry, but I’m sure my eyes looked bulbous and unusually filmed, for that was how they felt. My breathing was thrown off by some of the pieces; I felt a wonder, and a recognition. I felt emotional in a way that was both full and hollow. I wouldn’t have been able to say, with any truth, what it was about any of those paintings that made me feel this way. If you insisted, I’d have made up something which may have sounded eloquent, even profound, or may have stumbled out in some convoluted fashion. I had never before had this kind of first degree emotional response to art in a museum or gallery, and certainly never to abstract art. Of course, this had everything to do with me: who I was standing in those galleries, who I am today. But whatever the sources of this response, the effect was a completely new understanding of this art. Until this particular viewing of this particular exhibition, I’ve appreciated abstract art for its innovations in form, its deconstructions of the figurative, its intellectual conundrums, its challenge to knowledge and certainty, and its invitations to sense and know in new ways. But all of this was cognitive; if emotion arose at all it came from a secondary process of narrative meaning-making. This particular, January 2019, encounter with epic abstraction – mostly very, very large and very, very abstract pieces of art* -- was different in that these pieces simply in their size, form, color, and juxtaposition evoked a great helplessness and tearfulness. These words look silly and excessive, but my feelings at that time way exceeded these words. Which brings me back to Zora Neale Hurston’s sentence about eyes watching God. “They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” In my reading of this sentence, it’s not about faith in God, though the people she was writing about may well have been God-fearing. The sentence gets its power from bearing narrative witness to a moment of extraordinary humanness – only being able to live, only pressing to live, with all of its terror, helplessness, grandeur, consciousness, God. This was nothing so limited as “staring at the dark.” This was emotion, longing, life (and death) beyond words and cognition, but not reduced to animal instinct. Hurston has an animal figure – a dog – in the same hurricane-driven floods as her narrator, Janie, and the other people in “the muck.” The dog’s eyes were crazed, phenomenally “staring at the dark,” staring wildly at anything it could see, desperate to live through aggression. It turns out the dog was rabid. Even if Hurston hadn’t needed the madness for a narrative twist, I don’t think she would have said its eyes were watching God. I returned to the Epic Abstraction show a couple of weeks ago, eager to repeat and record my emotional experience of the first time. In the beginning, I thought too much. Feel, I told myself. That didn’t work. Then I just let myself write in response to pieces, and feeling returned, filtered through words, thinner, a trace, but there. Though I was not in a hurricane during that first visit to Epic Abstraction, and I was not – in a very real, palpable way – on the verge of dying, in retrospect I appropriated Hurston’s metaphor to understand my experience that first time. That first time, my eyes peeped through the art at God. That art, that day, expressed humanness beyond words and cognition, the fullness of human desire to live, experienced and expressed with the sensate and cognitive sensibilities of our complex bodies. We are not machines. One day an artificially intelligent entity may mimic, with great sophistication and nimbleness, every human function, but if it is cut off from corporeal humanness, it will only be able to formulate helplessness; it will not feel the helplessness of “eyes watching God.” What does all of this have to do with moral authority? For a long time I have been struck by the moral clarity and power of the writings – including fiction, non-fiction, and speeches – of people who’ve survived sharp and sustained exploitation by other groups of people.** More recently, I’ve had opportunities to work with people who’ve lived through histories and direct experience of sharp and sustained pain. I’ve had such opportunities before and I’ve risen to them well – thoughtfully, kindly, in facilitator-speak holding space for them to be themselves through the hard transitions of survival and being that they were living. But I was different in my recent, deep and lengthy, opportunity. I had my own experience of sharp and sustained pain. It was urgent enough that I couldn’t simply dismiss it as small relative to the pain of others, to the histories of grinding indignity and uncertainty that many others live with. Rationally I know my situation is not bad; of course I’m not teetering on the edge of physical or emotional survival. But, emotionally, I’ve had to contend with very real helplessness, and, in the work I had to do with colleagues in San Diego, I was inexorably pulled to feel it, express it, and connect it to the helplessness of others. In this work, my understanding of moral authority deepened. A few days ago, I grandiloquently told a group that I am currently deeply interested in how desire and emotion – especially love, fear, and shame – are foundational elements of moral authority. What is moral authority? one of them asked. Here is my answer, today: moral authority is the agency with which you relate to others, through words, actions, metaphors, images. It is essentially social, both contained by and spilling out of convention. In Buberian terms, it is the action of “I” in relation to “you.” In Biblical terms, in part via Jean-Paul Lederach, it is seeing the face of God, or not, in others. It is the living of desire and helplessness, mediated by socio-economic and political structures, shaped by linguistic possibilities and the grace or awkwardness of particular bodies at particular times, and expressed, consciously and unconsciously, in every act of living. Mostly, moral authority is expressed and heard as dogma or debatable logic – sometimes self-focused and self-serving, sometimes prosaic and parochial, sometimes ineffably greater-than and universal. In my view, moral authority gains an enormous power and tenderness when it draws on the lived tension between desire and helplessness, mediated by emotions that may be described as love, fear, shame, joy, anger, pain, and awe. Everyone experiences that spectrum of emotions. In my experience, those who are more aware of that spectrum in themselves have more clarity and kindness of purpose, whether within and in relation to the smallest units of dyads or families or to the largest of collectives and, even, to humanity and life in general. The Epic Abstraction exhibition surprised me by evoking my own helplessness at losing, and letting go of, my partner of twenty-eight years. Zora Neale Hurston gave me a metaphor for that helplessness. I’m still figuring out how that helplessness, and its attendant emotions, are shaping and will shape my actions in relation to others. Certainly, it’s already made me much more intensely aware of love in my life, love that I give and love that I get. It mostly makes me a kinder – some would say “softer”, lol – thinker (though a recent exchange makes me think that I am softer in some ways but clearer and firmer in others). It’s influencing questions and dilemmas in my fiction. I don’t yet know how the effects will show up in my political activity. We’ll see. A new Presidential election is coming up. The last election made me angry and hurt. It didn’t quite reduce me to helplessness, but I do feel fear and uncertainty and those, along with the thread of helplessness in my personal life, are shaping, will shape, the moral authority that drives my purposes and actions. * Notes on the structure and pieces, along with some photographs, are appended below. ** Parenthetically, I’ve also been struck by how slowly and in very limited ways such writings have been acknowledged, read, engaged, and drawn on by dominant groups. Raw notes on, and pictures of, the exhibition, first from my second visit, and then some memories from my first visit Coming up to the Epic Abstraction show from the southern end, I pass Kiki Smith’s Lilith, to me fearful and vigilant, sort of at the other end of desire and moral authority from Janie in Their Eyes Were Watching God. If you think of this spectrum as circular rather than a straight line with infinitely divergent ends, this end is the same as the beginning. To my eyes, Lilith looks like a precursor to Mystique in X-Men. A group of Euro-American people – two women and one man – just stopped to look at Lilith. Two of them are brightly, innocently, fascinated, especially by her eyes. The third, a woman, walks away saying, “It’s too scary, I don’t like it.” The first piece of art on my right as I entered the Epic Abstraction exhibition is New York #2 by Hedda Sterne. It’s equally divided between light and dark. Her signature is on the left, in the middle of the vertical plane. My eye is drawn to the dark, the tunnel, the sewer. My mind is working too hard to see and interpret form to allow attention to feeling. Next comes Cy Twombly’s Dutch Interior, which gives me the pleasure and permission of utter foolishness, at scale. “I don’t know what to do.” The artist is present in the action. Time passing. The space covered, not covered, done. Jackson Pollock’s November 28, 1950. Museum clickbait. Overseen. Too confident. Is it his ego I resist? Is it my ego that resists? Moving on. Clyfford Still’s 1950-E. I’m comforted by the burgundy at the bottom. It feels right, balanced, the burgundy, left bottom; blue, right top-ish. Much more black than white, as much grey as black. A comforting painting. The last painting in this first space I entered from the Lilith stair is Conflict (1956-57) by Alfonso Ossorio. My eyes were drawn to this piece when I entered – it’s opposite Sterne’s New York– but I left it until last. It makes me feel alive: the red heart, the three-dimensional explosiveness, with textured paint of varying thickness. The color palate is human – blood, shit, skin, bone. In the middle, more or less, of this first space is Barbara Hepworth’s Single Form (Eikon) (1937-38). I ignored this sculpture the first time I walked through this show, sort of dismissed it. What was that about? It’s too classic, too phallic, too heavy, too large, too squarely confident, too masculine, derivative. The sculpture feels like my past, unlike Lilith and Booker’s Raw Attraction (coming up). But when I force myself to look at it more closely, I’m moved by the wings of the pillar as it expands up a little, by the trickles or ripples down the sides of the square block pedestal, including on the broken corner of the block. Most of the paintings in the Pollock and Rothko rooms slip past me in their familiarity. Kazuo Shiraga’s red and black untitled (1958) is in the Pollock room, right near the entrance to the exhibition from that end. I like it a lot. In the Rothko room, his No. 21 (1949) stands out. It feels uncertain, fading. I expected it to be a significantly early or late painting, but it is dated right in the middle of his painting life. The other piece of art in the Rothko room that stands out to me is Isamu Noguchi’s Kouros, a very large sculpture made of pink Georgian marble. Kouros is a youth, male. This sculpture is not a young man. Or maybe it is. It’s smooth, confident, supple, large, and fragile. The room that really drew my imagination on this visit is the one dominated by Chakaia Booker’s poky, horny, piping, leaking vagina (Raw Attraction) in the corner of the room, flanked on the right by another very large painting (untitled, 1960) by Clyfford Still, this time red is the dominant color, not as comforting as 1950-E (which, by the way, looks ominous from this seat in front of untitled 1960; the black and grey merge from this angle). Still leaves a few light striations, almost drips in the black and in the red. One of these is in the black, right in the center, in the bottom half of the painting. It looks forgotten, a flaw he deliberately forgot. On the left flank of Raw Attraction is Mark Bradford’s Duck Walk (2016). Wow, what a fantastic painting, mixed media. It makes me come alive. The left panel is mostly white with yellow-mustard in the middle, the right panel is black in the middle, yellow swirling out. I see anime faces in the left panel. I like that there is no red in the painting. The color palette is spare. White, black, yellow, and some beige. [Comment added while typing these notes in: His name had sounded familiar, but I only now remembered why. He recently added What Hath God Wrought to the Stuart Collection of remarkable outdoor art at UCSD.] Completing this space are two of my favorite paintings in this show, in large part because they are side by side: Inoue Yūichi’s Kanzan (Cold Mountain, 1966) with stylized renditions of the characters for cold and for mountain and Franz Kline’s Black, White, and Gray, 1959. Almost ending the making of this space is Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 70, 1961. The emotional impact of these artworks in this made space is as much due to the curation, the placement of a work in the space and relative to other pieces, as to each separate artwork itself. And then there is the fabulous, hermetic, almost 21st century video game image – Judit Reigl’s Guano (Menhir), 1959-64, a layered painting: like history, like death, like a reproduction of fallowness – that transitions me into the extraordinary female-human-20th century space dominated by Louise Nevelson’s Mrs. N.’s Palace, 1964-77. -----End of direct notes --- The second trip, of necessity, because of a phone call I was committed to making, ended there. I don’t have notes from the first trip, all I have are memories that are now thoughts in the present. I remember loving the unapologetic size, steadfast standing in place, and geometrical complexity in monochrome grey of Mrs. N.’s Palace, surrounded by sharp-edged images created by men, and also rounded, even sentimental, images created by women. Reds drew me on that first trip as well. I gazed at Alma Thomas’s Red Roses Sonata (1972) and Elizabeth Murray’s Terrifying Terrain (1989-90), and felt the threat and harmony of each. I shied away from, then stared at, Thornton Dial’s Shadows of the Field (2008); now it looks ominously like a faded, tattered flag, millennia before a fossil, though this soft tissue of history and affect is lived in consciousness or disappears. The color palette of Frank Bowling’s Night Journey (1969-70), the yellow falling through the horizontal center, held me, though I found the continents distracting in how they historicized color and shape. Finally, the exhibition ended (or began, if you came in that way) with Yayoi Kusama’s No. B. 62 (1962): mostly evenly red shells or scales, in retrospect a carapace, perhaps the curved surface of that odd creature, a pangolin, laid out in two dimensions. Postscript: I was hesitant to post this piece, even after proofreading it and uploading the photos. This morning, a beautiful, sunny spring day in NYC, I had to make explicit the life and joy I also see in and through the helplessness and moral authority. If you live, you fall in love with life again (thank you, Andrea, for your Facebook cover picture), even if only in small ways, and in that falling in love, you claim life for yourself, and often claim it for others as well. Janie (and Zora Neale Hurston) did that, the Epic Abstraction artists did that. Reading Hurston, and walking through the exhibition, and looking at the sunlight today, I am doing that.

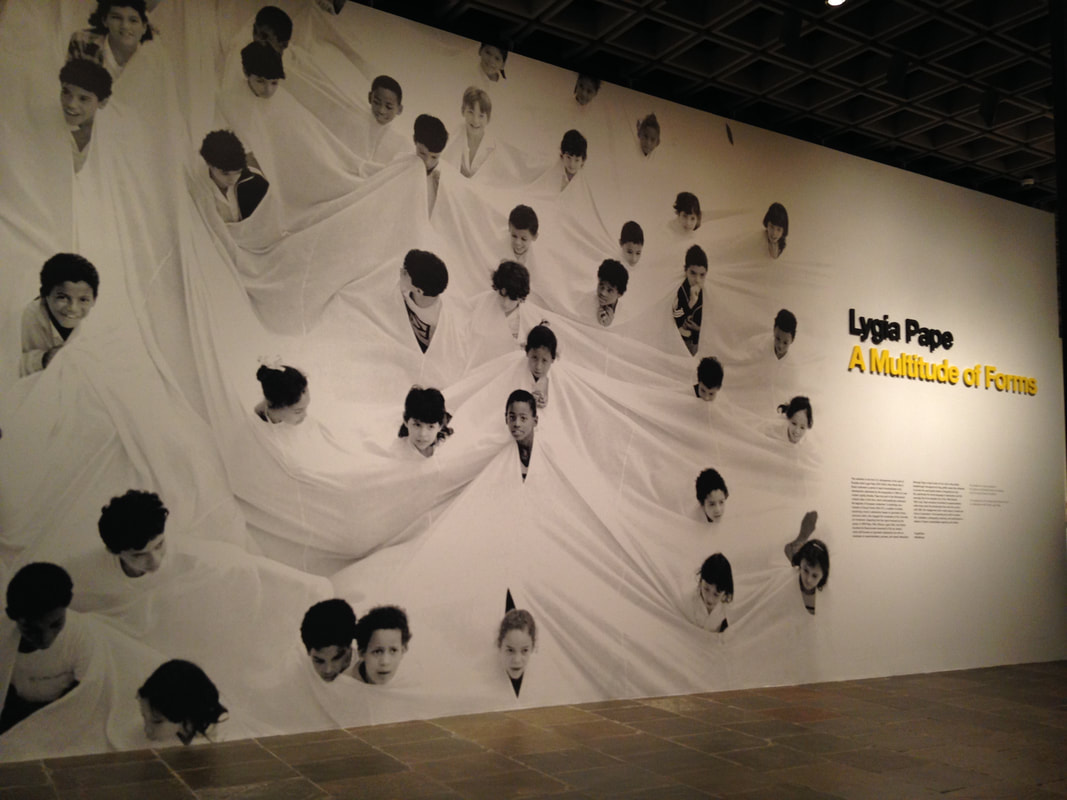

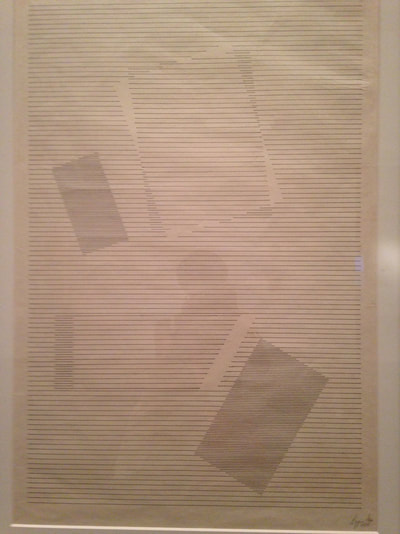

In the past it appeared that the engagement intention of art was to conjure a single bond, however illusory, between the viewer and art object before her. Supportively, the role of a curator was to present the art object in the best way to achieve that singular moment. Contemporary art, which seems loosely to be art created over my now-rather-lengthy lifetime, appears to have different and broader intentions, or perhaps these intentions have been laid upon it by the accelerated popularizing of art and the bolder actions of curators.* The curator in contemporary art seems to have developed into something between a composer and conductor, who orchestrates a dynamic multi-sense, multi-directional engagement between the art, context, and viewers, and invites the single viewer into a kind of performance which they** can choose to enact somewhat hermetically amidst wraiths, or somewhat chattily among other willing or unwilling members of an expedient ensemble. My most recent experience of contemporary art-watching happened in New York City, with a prelude visit to the Rubin Museum which presented “historical” objects in a winding, resounding, compartmentalized, but also fundamentally open and flexible, space. I went to the Rubin for the Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition and was properly astounded by the intensity of each photograph, each a composition by itself. I left the Rubin struck by the Buddhist iconography and sounds of the museum, which enfolded the more traditional presentation of the Cartier-Bresson photos, and conjoined easily the meditative, the erotic, the powerful, and the immanent. One could have chosen to visit only the Cartier-Bresson exhibition but that would have meant a deliberate shuttering of the senses, or an excision of a limited exhibition space – its photos, air, light, and walls – from a larger composition.*** The visit to the Rubin was a part of seven days of walking, working, eating, talking, thinking, and feeling in the city. The walking (around Williamsburg, the Village, from midtown to the upper west side, loitering, speeding, jostling), working (resisting and learning how to pitch and sell my first novel), eating (patatas bravas, Singaporean street food, Korean fried tofu, street dosas, a street hot dog, cauliflower tacos), talking (about politics, change, love), thinking (about strategy, living, composition), and feeling (the humidity of NYC summer, the grittiness of dust and burnt fossil fuels, the rhythm of slowness and speed sometimes under my control sometimes not) had inflated my sense of being, had created a sense that I had more, and more alive, nerve endings on a larger surface area. Wrought by this urban stimulation I went to see the Lygia Pape exhibition in the Met Breuer. This long, wandering introduction to a deliberate exhibition in an angular building is because my engagement with the Pape exhibition was primarily about movement; and movement implies, indeed requires, space and context. I went into the Breuer building and bought an annual membership (with a discount for being from far away), for I have been there before and will go again. Then I chose the stairs to revisit the curiously halted viscosity of Dwellings by Charles Simonds, a vestige from the Breuer building’s Whitney days. I climbed up to the floor with the Pape work and entered to a sideways view of the splash titling and image for the exhibition – A Multitude of Forms. The image combines uniformity – whiteness, children’s heads, all about the same size – and variation – in the way the white cloth dips and rises, in the very difference of each child. It is an exuberant and sobering image, conveying constraint, concealment, emergence, and movement. Only later did I realize that the image is a still from a movie which I viewed, and remember, as part of a course that included simple geometry – of the building, of Pape’s early work with the “geometric forms and pure colors” of the abstract art of the Grupo Frente; included, also, her later experimentation with naïve, semi-ethnographic film; and, finally, her return to geometry but now with pieces of unrestrained size and expression that jutted into the large spaces of the Breuer. The Breuer building enforces attention to perspective and the curator fully uses the building’s windows, ceilings, walls, and doorways to shift perspective from the singular art piece to the space, to the oeuvre, to other live bodies, to the outside in time and the outside in space, to both the merging of self through projection of self into something external and to the shocked separation of self from the exploitation of an image or a texture, both intended and unintended. My own movement was core to my viewing of this art, but, in addition, the movements of others became part of the art object in my viewing. One of the didactic plaques explains about the “Neoconcrete” tradition and intentions of Pape’s later work that “among the most influential outcomes of Neoconcrete art is the notion of an open work subject to the contingencies of time, space, and viewer participation.” It was humbling to find myself a textbook viewer of Pape’s art. I left the floor feeling like I had walked through a life, or in a long procession, more actor than spectator. Following a quick visit back to Dwellings, now merely landscape, I entered another show, THE BODY POLITIC, four experimental videos in dark places beyond an empty space: Five Easy Pieces; Phat Free; Love is the Message, the Message Is Death; and (down a corridor, separate) NoNoseKnows. In part because of time constraints, in part because the opening space seemed to offer me only two options, IN or OUT, and in part because I was already full, I gaped eagerly at the notices for each film and left the floor. Excision was easier in this geometric building than in the Rubin building.

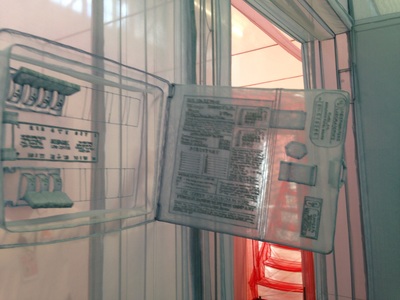

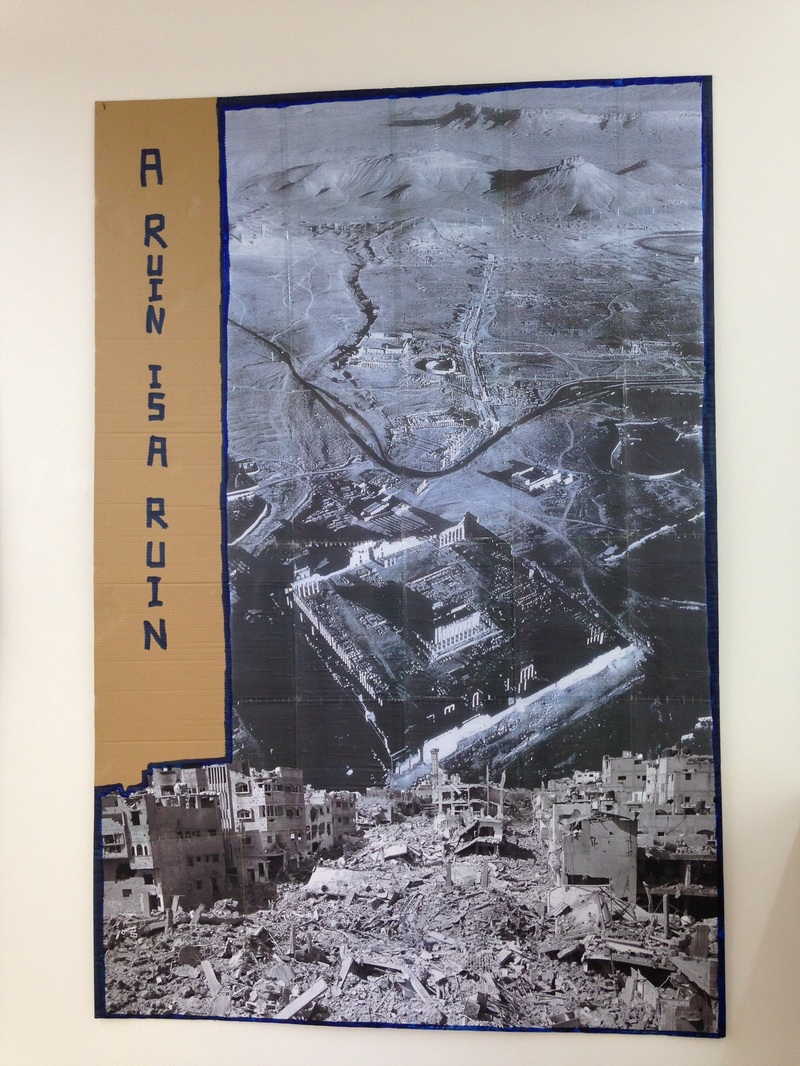

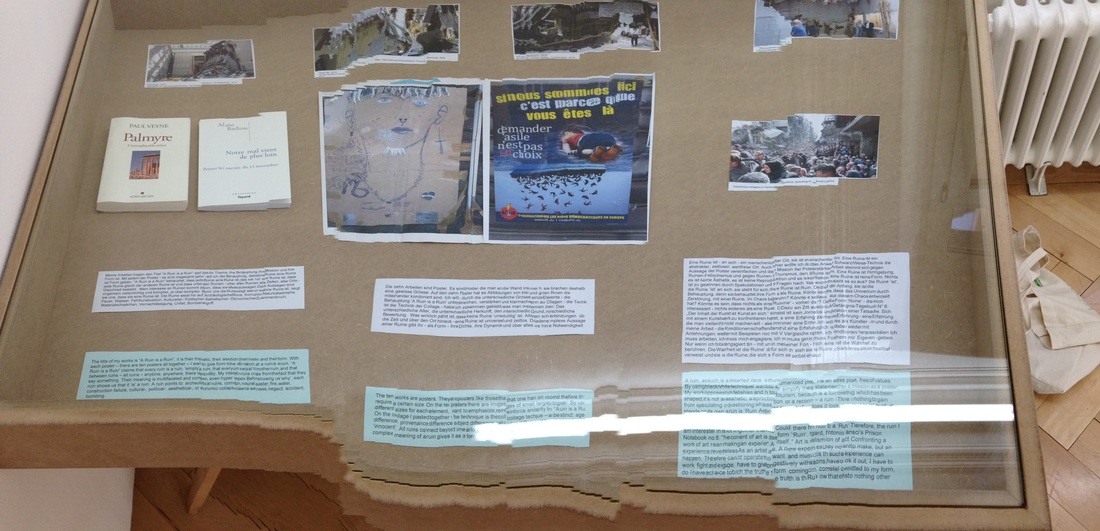

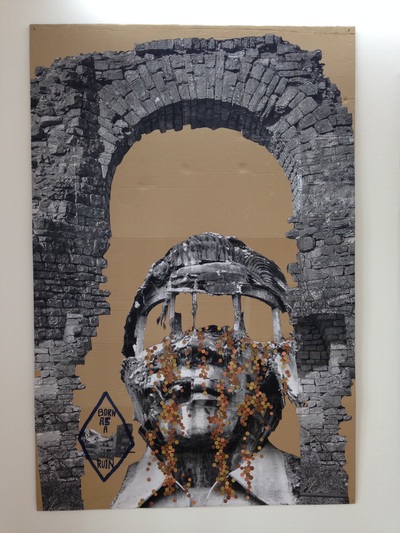

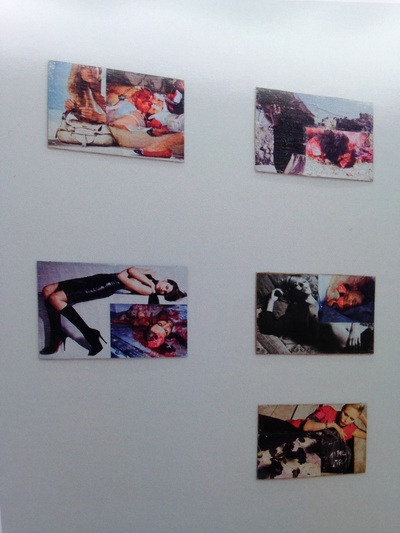

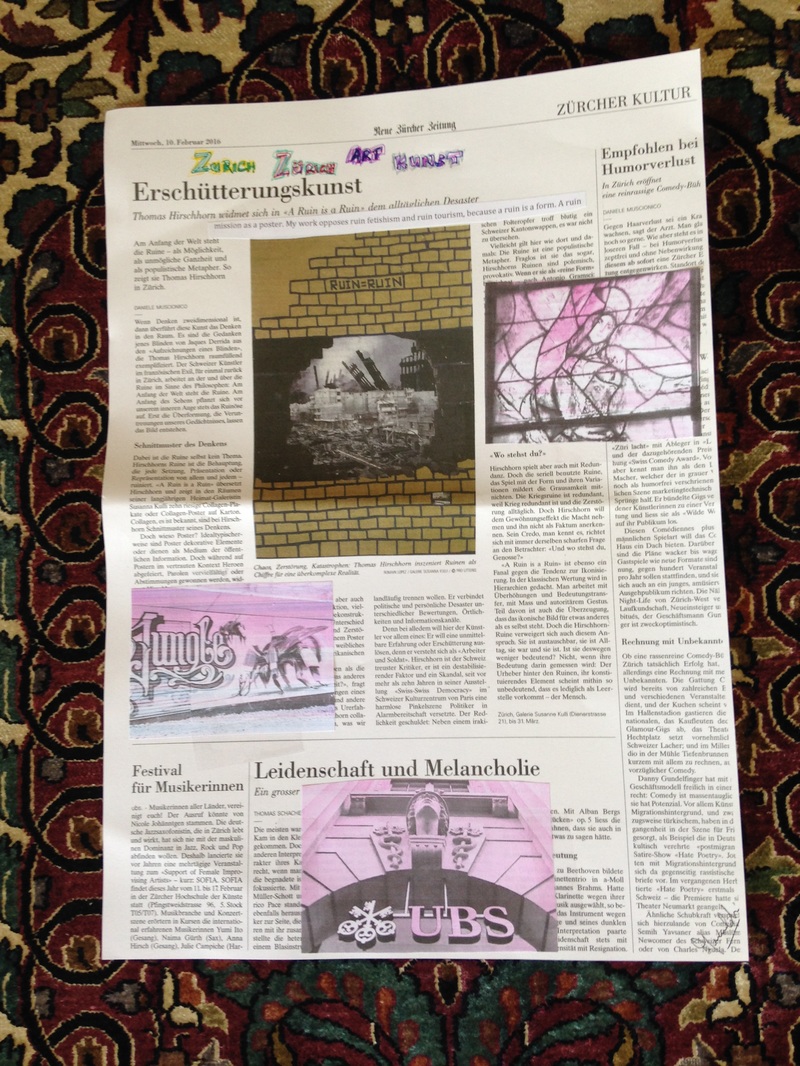

I went down to the basement looking for an outlet to charge my phone. After an excellent cup of tea, I returned to the street, moving – mostly forward, sometimes sideways, sometimes halting, stepping back – and observing as if my path was still curated, almost as if each object was still art and I was still performing. * My interest in contemporary art and sensitivity to curatorial work has been deeply influenced by my artist friend, Patti Fox, and my curator/artist daughter, Pia Chakraverti-Wuerthwein. ** After years of railing against the singular “they,” I have been convinced that it is a more inclusive pronoun than s/he. It is also more commonly used than my logically preferred pronoun “ze.” *** I have no photographs of the Cartier-Bresson exhibition because photography was forbidden in that section. In this period of increasing attention to walls, national boundaries, and trade protections, even as we experience climate-change-without-borders, are wirelessly entangled within an internet-(mostly)-without-borders, and watch global-access-flyers – grumbling far above slow-travel-migrants – move faster through every line in an airport, Gabriela Montero’s Ex Patria and Do Ho Suh’s obsessive recursions of “Home” extemporize on old-fashioned nostalgia, while Harrison’s “[Nest]” traces the delicate immediacy of a home qua home. Montero lives in exile in the United States and Do Ho Suh creates art – drawings, netted forms, and simulacra – all over the world while scattering residence across Seoul, New York, and London. Harrison was born in Germany, grew up mostly in New Hampshire, and lives in Maryland. Montero, a political exile, wrote, and plays, Ex Patria in the tradition of the Russian composers of the first decades of the twentieth century, fiercely longing for a beauty that was a promise of youth. The piece, dedicated to the people of her native Venezuela and a memorial for the 19336 people who were murdered in that country in 2011, conjures the memory of an “old country” that is wounded, potentially mortally. Over the four years or so since Ex Patria was first played, Montero’s implacable rejection of the current Venezuelan regime, including its extraordinary musical program, Sistema, for over 500,000 youth, has amplified the piece’s political narrative. Starkly, Montero’s critique of Sistema as a fig-leaf for a criminally dysfunctional government calls for letting the bubble of music pop, so to speak, to say “NO,” to wipe the body politic clean, and start anew. Ex Patria expresses the tragedy of the bubble, Sistema’s success and beauty growing in a fundamentally toxic and violent society, and its inevitable corruption.* Suh is not an exile like Montero. His existential mobility is unmotivated, like the life-cycle mobility of a firefly. He explains, “Once my fortune teller told me that I have five horses and that means that I travel a lot….” Embodying a form of mobility that is shaped by the technologies that are laid into our time, his nostalgia is for the form of home: the skeletal underframes, the permeable walls, the obtrusive shapes of haunting exits and entrances, including doors, windows, electrical outlets, and air conditioners. He is, perhaps, best known for his gossamer recreations of his apartment homes, but the most nostalgic piece, the most riveting for me, in the exhibition that is currently on at the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, is the piece that combines a miniature version of his traditional home in South Korea (placed on a truck) with a film that traces (or affects to trace?) the journey of the home to Madison Square Park in New York City. Suh seeks to carry “home” like a snail, a virtual snail with a virtual home, mind games, in which all of “home” resides in him, or he is always home. The exhibition in San Diego is presented across four spaces. Along with my local artist friend, Patti Fox, I walked through the two gallery spaces of the Museum, which are next to San Diego’s main train station and the downtown trolley hub, respectively, and separated by a wide road. We started at two o’clock in the afternoon, so the sun was very high and bounded the interior spaces so intensely that I couldn’t avoid attention to the very specific concatenations of radiant light, shadow, translucence, darkness, and projected light as we walked through one exhibition space to another. Suh, to my delight, is obsessively specific. His drawings have fine, straight lines, repeated one after the other until the image is complete. He sticks thread on paper to create figures and stories in which each loose end is perfect. His rubbings of every apartment wall, outlet, plaster pimple, and stovetop draw the viewer into mimicked attention to the banal phenomena of “home.” And his fabric simulacrum of his New York city apartment has astonishingly detailed embroidery and seams.** If Leslie Harrison’s “[Nest]” has nostalgia, it is very brief. The poem captures the fragile uncertainty of time, space, and fluttering materials that a nest represents. At some point, the elegiac home country of Montero’s Ex Patria and the obsessive scurrying of Suh’s “Home” recreations had their origins in wavering, delicate, and fundamentally physical moments like “this lodge that takes the shape of a wasp’s nest paper and swaying.” While Ex Patria bellows the loves and deaths of the multitudes that contain home, and Suh weaves them into nets that look repetitive and forever and then you notice that the figures vary and the nets cross continents, [Nest] whispers “the people on shore wave small scraps of fabric they’re white in the dusk.” Reading Harrison’s poem, with “heart” close to its geometric and literary center (“the heart goes dark the heart becomes just one more vessel waiting”), alongside Montero’s brief concerto and Suh’s art, I glimpse and want to capture how the three together represent the immediacy, mobility, and nostalgia of “home” in the 21st century, but I’m defeated by the over-determined neatness of my synthesis. And so I will stop here. *A contrary view of Sistema, held for example by Gustavo Dudamel, sees it as a hopeful program, preparing youth to be better citizens, morally and otherwise, who eventually will build a more beautiful tomorrow. **In my home city, San Diego, Suh has created a “Fallen Star,” a tilted house perched on the edge of a tall building for engineers. It has a lovely garden in front and pretty furnishings inside, and provokes an impossible imbalance when you enter it. When you leave it though: from the outside, from far away, it becomes a metaphor, an empty signifier, a wish. Thomas Hirschhorn A Ruin Is A Ruin Galerie Susanna Kulli, Zurich, Switzerland January 27, 2016 – March 31, 2016 A few weeks ago, in the middle of February of 2016, on my day off work in Zurich, I went to the Galerie Susanna Kulli to look at Thomas Hirschhorn’s collages on A Ruin Is A Ruin. I walked from the Hauptbahnhof, the main station, down a “military” road and past ordinary, tired buildings. A few steps led into a small gallery. Immediately before me was a large, undulating piece of cardboard, presenting a striking foundation of ruins from which an isolated ruin rose and gave way to a wasteland. A message in awkward orthography proclaimed what at first looked like: A RUIN ISA RUIN. Almost immediately I turned away from the large poster, putting my initial, peripheral view of more posters behind me, and turned to the collection of simulacra and writing under the glass of a small display case next to the entrance. In Hirschhorn’s terms, I turned from the art to the information. Hirschhorn is explicit about his aims in his writing and interviews. “Affirmation,” in the manner of Warhol, and “truth…that refers to nothing other than itself and asserts itself as a form.” His Ruins posters are layered, acquiring a three-dimensionality from both the vertical and lateral pasting of images, as well as from the building of the poster with a bottom and a top and an architecture that leverages height. Most of the posters have letters, usually words, usually including Ruin, in one case an overlapping RR, unavoidable persiflage of a monogram. The coda is provided on a small scrap of cardboard, in size a fraction of the large posters, on which is pasted the image of an indisputable ruin, accompanied by an honestly handwritten (uneven, with mistakes scratched out) text from Derrida: “… And then I would love to write, maybe with or following Benjamin, maybe against Benjamin, a short treatise on love of ruins. What else is there to love anyway? One cannot love a monument, a work of architecture, an institution as such, except through the experience, itself precarious, of its fragility: it hasn’t always been there, it is finite.” While the Derrida quotation and Hirschhorn’s Ruins collages both exclude people, connecting this exhibition to Hirschhorn’s earlier work on Ur-Collages (his collages presenting beautiful and ravaged bodies) leads me to suppose that love, loving people, also requires fragility, finitude. “A ruin is a form,” Hirschhorn says, and quotes Gramsci, “the content of art is art itself.” In a very ordinary way, I would propose that the content of art is also what it is not, what it excludes. In that sense, Hirschhorn’s A Ruin Is A Ruin exhibition both excludes information and surrounds itself with Hirschhorn’s own words, the Derridean coda, and layers of ancestral rubrics. So each poster is a form, “a truth… that refers to nothing other than itself,” and my delight with his work arises from the question: what is it not? The question what (each poster; the exhibition as a whole) is not implies a relationship to what it is not. In my encounter with the exhibition in Zurich, I found myself noticing four relationships: to information; to discursive and disciplinary context; to physical/spatial context; and to the agency of the viewer. I have written above about the relationship to information: both its deliberate exclusion, and its being hugged close via the coda and rubrics with long genealogies. This relationship to information merges with the relationship of the art to discursive and disciplinary context. In his interview with Sebastian Egenhofer on the occasion of his 2009 exhibition of Ur-Collages at the Galerie Kulli, Hirschhorn plausibly rejects (his own) consideration of “the public sphere of the art scene,” and, most understandably, even trivially, sees his work in relationship to that of Piet Mondrian, Andy Warhol, Martha Rosler, Caravaggio – a few of the artists explicitly named. His A Ruin Is A Ruin, interpellated by a Derridean coda, is also fundamentally present through its distinction from and location relative to other works (and subjects) in “the public sphere of the art scene.” Walking away, the relationship of the exhibition to physical/spatial context becomes evident, as I observe the slow dissolution of the urban landscape from the reserved, classically bourgeois buildings around the gallery to browning sidewalks that took me to a tunnel that stepped me through staccato colors out into an area of subsidized housing where I found walls with rounded, nature-sci-fi murals, Journey through the Jungle, all of this far from, and related to, the beautiful Altstadt and the heartbreakingly lovely contradictions of the Chagall windows in Our Lady’s Church. Hirschhorn’s ruins were there, then, in the middle of that geography with its particulate, too-big-for-one-telling histories. The collages in A Ruin Is A Ruin have a seductive beauty. Only one contains an obtrusive human (dis)figure, and that highly stylized. But this exhibition’s antecedent in the same gallery, Hirschhorn’s Ur-Collages, contained works that each displayed images of glossily beautiful humans and ravaged bodies – dismembered, flesh, entrails, blood. The gallery assistant, Anna Vetsch, who will one day run a gallery or museum of contemporary art, showed me photographs of that exhibition and warned me that they would be hard to look at. Remarkably, the images of that earlier exhibition did clarify my attention to the current Ruins exhibition, and, yes, the images were difficult to look at. I did not want to look at the disfigured human bodies; and I was not interested in the fashion photographs to which they were attached. I was curious about the compositions, but didn’t want to look at them. And then I read Egenhofer’s interview of Hirschhorn in which Hirschhorn says: “I am astonished time and again when viewers say, ‘I can’t see that,’ or even worse, ‘I don’t have to see that’ or ‘I don’t want to see that.’ That is an incredible thing to say, that is an exclusion of the other, and it is pure egotism when someone claims that he has the option of not seeing. Of not seeing the world as it is. That is an incredibly luxurious thing to do, a self-segregation, a turning away from the world that I will never understand.” So when Hirschhorn challenges the agency and choices of the viewer with his Ur-Collages, we can only suppose that, with his Ruins collages, he is also challenging the agency and choices of the viewer. His works ask – When you turn away from the Ur-Collages what do you look at? When you look at the Ruins collages, what are you turning away from? Contrary to Hirschhorn’s apparent intention, the truth of his work is not simply in the art itself. Perhaps there was only one moment of that truth when I viewed the exhibition, the moment when I walked in and glanced at the first poster before turning to the information encased in the glass. Perhaps there was a moment of truth for each work, a truth that became available in a brief liminal pause, during which the image hung separate, preceded and followed by inevitable captivity to context and information. The longer truth is that Hirschhorn’s work caught my attention, led to this writing, and will “hold up” because it must be seen within its larger contexts, which are specific and granular around this art, today, but schematized by the form of the work in ways that make contexts of other times and places relevant and questioned. A note about the photographs: All the photographs are taken by me with my iPhone. The photo showing some of the works in the Ur-collage exhibition is of a page in the booklet containing Sebastian Egenhofer’s interview of Thomas Hirschhorn. The booklet is available for 18 euros at the Galerie Susanna Kulli, which organized the interview and has published the booklet (bi-lingual in German and English). The last photo shows a keepsake collage that I created on a photocopy of the review of the exhibition in a Zurich newspaper.

|

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed