|

The children of today become the grown-ups of tomorrow. The grown-ups of today are the children of yesterday.

Many years ago I was invited to a fundraiser for a program called Hands of Peace which created space for Palestinian/Arab and Israeli/Jewish teenagers to live together for a few weeks and engage in full and honest encounters. The children spoke at the fundraiser and from what I could tell they had many very important and very challenging conversations. How challenging? Think how challenging it is today to talk to someone who thinks even a little differently from you on the topic of Palestine and Israel, leave alone people who think “Israelis” are the bad guys (as if all Israelis are the same) or “Palestinians” are the bad guys (as if all Palestinians are the same), leave alone people who because of deep relational or cultural or historical connections to Palestine or Israel, and to the suffering woven into each of those histories, feel that each word — just listening to it — has the potential to destroy or at least draw blood. These children did it. Held by Hands of Peace, they had these conversations. They didn’t, indeed couldn’t, solve the conflict, but they created a tender foundation of relationships that the grown-ups they would become, perhaps, could draw on to build peace in their region. As I write this, I am sad and somewhat fearful thinking of those children, now in their late twenties. Who are they now? How are they? What’s left of the tender foundation of relationships? A silent auction was one of the mechanisms of the fundraiser. A box with an embroidered cover was contributed by a young Palestinian, a girl if I remember correctly. A large metal hamsa hand was brought by a young Israeli, a boy, as I remember. They looked like elements of home, they looked like they belonged in a home, and I could afford them, so I bid for them and now they are side by side in my living room, in a central place. I brought these objects to my home many years after some work I’d done with Palestinians and Israelis, whom I’d grown to like and respect, all of them. That work happened at a time when I still hoped for change. Then, as one barrier to peace after another was layered and stacked, often with the blood and tears of someone, or someone else, and sometimes with the bland words of political and bureaucratic “strategies,” I looked away. The box and the hand stayed in my living room in a central place, perhaps silently holding hope. Perhaps those children will…? And, now, I have been shocked out of my looking away, though I’m tempted to look away again. I could look away, utter some platitudes, and look away once more, but I will not. This time I will not look away and I’m writing this to ask you not to as well. This is not simply about safety, land and dignity, ceasefire, or justice, though all of those things are important for Israelis as well as Palestinians. It’s about the children. It’s about the grown-ups we want tomorrow. While the violence and kidnappings committed on October 7, 2023 by Hamas militants were unambiguously cruel and wrong, I knew they would be followed by “lawn-mowing.” As I struggled with external and internal responses to the Hamas violence and Israel’s relentless bombing of Gaza, killing and maiming tens of thousands, destroying homes and hospitals, along with a sideshow of beatings and vandalism in the West Bank, I went back to writers I’ve admired: Mahmoud Darwish, Amos Oz, David Grossman, Naomi Shihab Nye. I read news commentaries carefully, looking for more than escalating fear and hatred; looking rather for kindness and empathy that goes both ways even if not quite symmetrically, for glimpses of generosity in the midst of anger and pain. I created a conversation of sorts among poets and writers, using quoted excerpts of their work. As I read the conversation I’d composed, I wondered why everyone doesn’t see: there’s beauty here (I look one way) and there’s beauty there (I look the other way); there’s pain here, there’s pain there; there’s anger here, there’s anger there; there’s kindness here, there’s kindness there; there’s love here, there’s love there; there’s fear here, there’s fear there. I want to write — it fits the cadence of the words and the sentiment cloud I am conjuring up — there’s hope here, there’s hope there, but I can’t. There isn’t much hope, here or there. If we care about that region, it’s up to us to create space for hope for all the peoples of Palestine and Israel. And I believe that the content and direction of the hope can only be a fair, robust, and viable peace process. It can be slow, it can even be angry, so long as anger is seen, as I learned from Audre Lorde, as a “distortion of griefs among peers.” Indeed anger in this context is a distortion of griefs, but can Israelis and Palestinians see each other as peers? Do we in the rest of the world hold them as peers, hold space for them as peers? If anger is not expressed and understood and explored as a distortion of griefs among peers, it drops into hatred, and “the object of hatred,” as Lorde puts it, “is death and destruction.” Peace does not mean stepping away from anger, “for anger between peers births change, not destruction, and the discomfort and sense of loss it often causes is not fatal, but a sign of growth.” (from “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism” in Sister Outsider) Scouring the news for reasons to hope I watched a brief video on The Washington Post website that shows displaced Palestinian teenaged boys doing parkour, watched by delighted little children. A teenager who is interviewed explains that it’s an outlet from the stresses of the war and the delight of the little children makes him happy. I watched it thinking of David Grossman’s wish. In his essay, “Contemplations on Peace,” he writes: “I conclude with one more wish, which I once expressed in my novel See Under: Love. This wish is uttered at the very end of the book, when a group of persecuted Jews in the Warsaw ghetto finds an abandoned baby boy and decides to raise him. These elderly Jews, broken and tortured, stand around the child and dream about what they would like his life to be, and into what sort of a world they would like him to grow up. Behind them, the real world is going up in smoke, with blood and fire everywhere, and they say a prayer together. This is their prayer: “All of us prayed for one thing: that he might end his life knowing nothing of war … We asked so little: for a man to live in this world from birth to death and know nothing of war.” (in Writing in the Dark) This wish — my wish, your wish I hope — is not just for happy children, it’s for the grown-ups — whether Israeli or Palestinian— who can be so much more if they are not consumed by fear of destruction and destructive themselves. Little children are sweet and innocent and, of course, we don’t want them to be harmed. But, as importantly, these children grow up to be the grown-ups who govern our world and the world of new generations of sweet and innocent children. Wouldn’t you want grown-ups who know and can give generosity and joy, because they have received it, rather than grown-ups who live with grieving and fearful barriers, hardened by and into hatred, barriers which open more easily to violence than to generosity?

1 Comment

Madre and desmadre

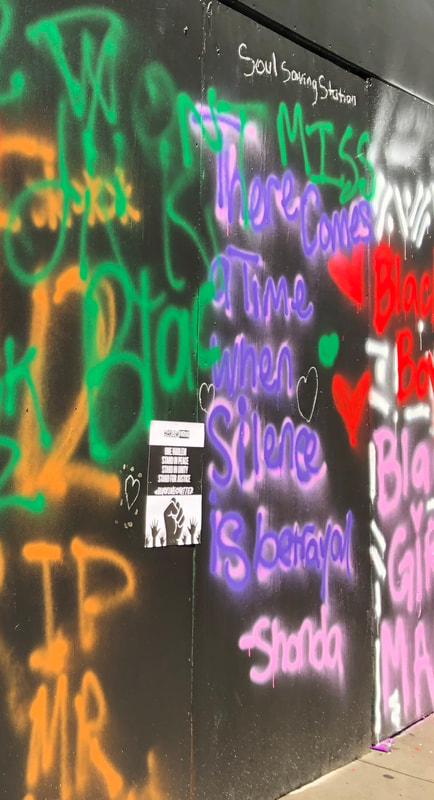

I very recently became aware of a Spanish word desmadre, first spoken more generally in my presence and then directly to me by a group of magnificent women in the centre of San Diego. I was told desmadre means ruckus. The way I heard them use the word, it sounded like John Lewis’s “good trouble.” I thought it was two words. Of mothers? No, no, I was told, one word, meaning ruckus. The word intrigued me. Does it have something to do with madre? Well, of course it has something to do with madre, I found. It comes from a root of separation from the mother. Disintegration. Chaos. And now good trouble. In my three works of fiction, all the main characters are women: two wandering mothers, one grandmother, many daughters. My first and third work are about separation from the mother, in one case chosen by the mother, in the other not chosen by the mother. I wanted to close these books, close the stories, go from heimlich to unheimlich to heimlich -- the formula for a good novel I was glibly instructed by a literary agent with unliterary tastes — but the characters are broken are broken, whole only in the luminescence of the world in which they live, loved and loving. Earlier this year I presented the artwork edition of my first novel, Night Heron, in Berlin. My daughter introduced me, moderated the presentation and asked me how I came to write this novel about a visual artist who leaves her son for no very good reason, neither heroic ambition nor poor traumatic past. For the first time in all my stumbling, convoluted speaking about this novel, I spoke about the motivating ambition for this story. It was simple and too ambitiously silly to be spoken of before this, but there in Berlin, speaking to my daughter and a group of mostly artists and writers, I said I wanted to create a female Stephen Dedalus, as in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which I had loved as a young woman. I wanted a woman to step out as vividly: the language, yes, but also that stepping out. I found no Dedalus. There was no easy Dedalus, no female derivative who felt remotely real or interesting. My own life at the time — a mother of young children — pushed me to the not-Dedalus figure of a mother of a young son, and then she leaves her son, which is experienced as desmadre by all readers, disturbingly and uncomfortably so for most, satisfyingly provocative in a melancholy way for some. Art and writing has often propelled or reflected desmadre, traditionally in most parts of the world in the voices and through the agonies of men, often men with, or aligned with, more power (though they could and often did write about men of less power and even women). In the last couple of centuries that has changed. This change has become more rapid in the last sixty years or so as women and traditionally less powerful men — less powerful at least in the context of our long modern era of military gunpowder, industrialization, colonization, and rampant capitalism — have explored what it means to articulate main characters from their own experience of work and living in crowded interior and exterior worlds. Which brings me to an early stimulus for this blog post. A few days ago, biographyof.red, an extraordinarily delightful Instagram account that evidently springs from Anne Carson’s work and posts mostly poetry, posted an excerpt from Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. The excerpt, in turn, quotes Henri Bachelin on the conjuring of myth - involving “tragic cataclysms” of the past, and ends of times — around winter hearths. Evidently this conjuring comes from men, most definitely not old women who tell “fairytales.” Bachelard’s and Bachelin’s lovely words inscribe the space in which old masculinist myths can loom. Their words projected to me a willfully blind desire for understanding that penetrates “the end,” that grandly foresees its own tragic failure. I refused this space and asked myself, what larger space do I make, what poetics if life is the hurling of oneself — whether slowly, grandly, or awkwardly — against the hard transparency of end? What poetics, what space for people living splintered lives — loving, working, laughing, living — and expiring despite themselves, where narratives of yawning pasts and distant ends are often unheeded? Yes, yes, I know, Shakespeare, Dickens, the novel. And, yes, how does this relate to madre and desmadre, apart from the obvious gender stuff. Well, yes, the obvious gender stuff is key. Madre, a trope for connection, with all its connotation of home, gathering, shared food, shared corporeality, cooking, fire, transformation, sometimes even hearth. Complaints, shush, small tales, snoring, reaching into “forces and signs” by women and men. Desmadre, inside and outside. Inside and outside bodies, inside and outside that gathering at the hearth, inside and outside the home, heimlich always roughly pixilated, parts spinning into unheimlich, unheimlich pressed into new forms of homeliness by personal and collective intimacies. From trope to subject, madre to desmadre, women and the historically less powerful are saying we will occupy this hearth, we will make the space under crossing highways a hearth, we will make it a space for life, for gathering, for drought-resistant plants, for art that exclaims “we are here!”, and here encompasses the beauty and pain of our pasts, the struggles and dancing of our present, and our shared future of children, life, and death, all of that! I didn’t know how this blog post would spin out. It is still spinning within, tilting into aliveness, spilling into uncertainty. Madre and desmadre are mythical figures of worlds that have long been binary-gendered. As binary gender dissolves into two figures in a much larger flow, or if gestation becomes incubation in genderless machinery and separation becomes connection to a human, will madre — traditionally female, one of a binary, bloody and corporeal — change? I don’t know. The best I can do for now is to observe that the binary was always only a device, a tool for organizing rhetoric and meaning. The non-binary has always been available, residing in both vast madre and desmadre. Reflecting on the mothers in my fiction and the space-making event alluded to above, madre also seems to connote separation and desmadre also connotes connection, gathering. Note: The title of this blog piece is exactly the same as, taken directly from, a book by Alice Walker. I have not yet read that particular book, so this blog piece does not refer to its content directly. I have read other work by Alice Walker. The story of how Alice Walker’s title-phrase came to me is in the blog piece below. As the contours of this blog piece have emerged over the last two weeks, it became increasingly clear that this was the right title for it. On May 22, a little less than three weeks ago, my eye was caught by the tagline of an op-ed article in the NYT:* “Better to love your country with a broken heart than to love it blind.” The title of the article was Germany’s Lessons for China and America. The tag line was drawn from something the current President of Germany, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, said in relation to the 75th anniversary of the end of WWII in Europe: “Germany’s past is a fractured past — with responsibility for the murdering of millions and the suffering of millions. That breaks our hearts to this day. And that is why I say that this country can only be loved with a broken heart.” I have seen this phenomenon of loving, or struggling to love, with a broken heart in myself and in others, in relation to people in our lives and in relation to the communities and countries we call “mine” and which have shaped us. People who live in dominant majority communities, as I did growing up Hindu in India, sometimes take a while to feel and understand this phenomenon of broken heart in relation to one’s larger community/country. It took me layers of learning, layers of foolishness, over decades. In 1980, I came to college in the United States, like most people having had some personal challenges (practical, emotional, existential) but generally comfortable in my external identity of (majority) Hindu, well-educated (class-privileged), Indian (heterosexual) woman. Yes, I was vocally feminist and spoke up against injustice as I saw it, but in both cases I felt largely secure in who I was, and surrounded and supported, sometimes prodded, by feminist/left-leaning forebears and peers. My first somewhat conscious encounter with what I might now call loving one’s larger community with a broken heart I remember with shame. I asked another student at my college who was Jewish Iranian whether she felt more Jewish or more Iranian. It was a genuine question and I was struck (silent!) by how much it seemed to hurt her. I did see and hear how deeply that question evoked a negative reaction. It both seemed to miss the point and deeply hurt her. I didn’t know myself well enough to know how to seek further understanding. I never got to know her well enough to come to an interactive understanding of myself and her through the foolishness of that question, and so this retrospective understanding on my part is still partial. Her understanding may or may not coincide with mine. Fast forward to the mid-nineties. I was waiting for my older daughter’s pre-school day to close, just sitting in some random outside space when I was joined by some random man. We started chatting. It turned out he was Jewish and had grown up in Russia. I don’t remember the details of the conversation. He was an erudite and eloquent man and we spoke about Russian literature and music. He knew a lot more than me, which I always love. I don’t remember any details. What I do remember is how deeply he loved Russian literature and music and how much he hated Russia. When I read Roger Cohen’s May 22 piece, I recognized what Steinmeier said. I’m not sure all Germans consciously feel what he expressed, but the question of how you love your country and by extension yourself is a live one for all Germans since WWII, I believe. It took the Holocaust and WWII to make that majority community contend with its own broken heart, to feel the violence embedded in who it is, to see that violence, to face the emotional violence that it has generated and potentially generates, and to struggle with how to love and to love itself with that broken heart. I use the collective “majority community” and the impersonal “it,” but this plays out in individual people, individual hearts, each in its own way. Usually when emotional violence is committed – often enough but not always accompanied by physical violence – the bulk of the resulting emotional work is left to those who suffered and survived the violence, with such effects extending to their loved ones, their descendants, and their communities. The experience of emotional violence and its effects are most obvious in, and to, those who are on the receiving end of such violence, but it also affects, profoundly, the soul and integrity of everyone in that system, whether direct perpetrators, witnesses, bystanders, or those who turn away, dissociate themselves. Fast forward again to about two weeks ago. Angry, heartbroken, and feeling helpless after the video of Amy Cooper in Central Park and with news breaking on the killing of George Floyd by a police officer openly in the presence of other police officers and ordinary people – neither of these new or unusual events – I was conversing with a writer friend, thandiwe Watts-Jones. I spoke about my own anger and heartbreak. I mentioned the Roger Cohen article and the Steinmeier quotation, focusing on the phase “this country can only be loved with a broken heart,” and she pointed out that Alice Walker had written, “the way forward is with a broken heart.” Of course. Today, I am a citizen of the United States of America. I have lived in this country for forty years, about two-thirds of my life. I have been a citizen for a little over fifteen years. I love this country and I am deeply critical about many things here: many of our policies, our current President, the stark structural inequities of our society and economy; and our resistance to facing the physical and emotional violence, particularly to Native Americans and African Americans, that is centrally part of our heritage. I love the music and artistic work of Americans.** I love the brashness of American culture. I love the way Americans come from all over the world, as a result of which we live with immense complexity. I am proud of the stated Constitutional commitment to “freedom, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all.” I became a citizen when I realized that while I am very opinionated politically, I had never voted in any country. I left India before I started voting, and then for more than two decades lived in the United States as a “legal alien.” What this meant was I referred to “you Indians” when I criticized something in India, and “you Americans” when I criticized something in the US. One of the central reasons I became a citizen was to hold myself politically accountable. I didn’t vote for Donald Trump, but I am accountable for the government of the United States. From that sense of political accountability I have grown to know that, as an American, as a citizen of the United States, I also hold accountability for the history of the United States, for what it means to be American, including the hegemonic intonation of “American,” and including the emotional and physical violence of my heritage as an American. What I am as an American today, even being a relatively recent immigrant of color, is also founded on dispossession of Native Americans and the continuous weave of slavery, racism, and anti-Blackness in our history. For several centuries until right now in 2020, we Americans have allowed African-Americans to carry disproportionately the risk of death and other physical violence as well as most of the emotional burden of slavery, racism, and anti-Blackness in our culture. Some form of color- and race-related anger and heartbreak is chronically part of African-American lives. African-American writers and speakers have told us this repeatedly. They’ve told us how their children are taught to watch out for and avoid the risk of being killed, and to expect and overcome risk of humiliation, all this only because of their “color” and “race.” And they’ve taught themselves and their children how to love themselves in the face of indignity that is often intended, sometimes unwitting, how to love themselves and this country with a broken heart. One outcome is that African-Americans have done some of the most extraordinary soulwork of any group of people at any time in history.*** The rest of us – not just Americans, the world! -- have drawn on their soulwork, expressed in music, writing, art, and inspirational leadership. Martin Luther King Jr, Audre Lorde, Malcolm X, Zora Neale Hurston, Frederick Douglas, Oprah Winfrey, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Ta-Nehisi Coates, bell hooks, J. Saunders Redding, Alice Walker, Langston Hughes, Rita Dove, Ishion Hutchinson, Jesmyn Ward, Kendrick Lamar, Nina Simone, Gil Scott Heron, Shirley Horn, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Abbey Lincoln, Jimi Hendrix, Janelle Monae, John Legend, Meshell Ndegeocello, Kamasi Washington, Regina Carter, Noname, Chance the Rapper, Tierra Whack, William H. Johnson, Betye Saar, Romare Bearden, Bisa Butler, Nari Ward, Ja’Tovia Gary, Spike Lee, Simone Leigh, Jeremy O. Harris, Lupita Nyong’o. I could go on. I know some of the work of every one of these people. These are just a few of the African-Americans whose work I have experienced as immensely generous to me and to the world. This brief video made by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre illustrates what I am trying to tell you in this paragraph better than anything I can say.**** Last Christmas, I gave my two daughters Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider, in part because they might learn something about being American and being feminist, but mostly because Audre Lorde is a profound guide in soulwork for anyone, anywhere. When I read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, I suggested that any man should read that with his son. It’s a hard book if you are “white” and live the “American Dream,” but if you get past your defensiveness you will see it is also about engaging with the complexity of the world, about heartbreak, about loving and nurturing and protecting your child in the face of complexity and heartbreak. If you feel into your defensiveness, you will learn a LOT about anti-Blackness in the United States. In ordinary ways many of you – across the world! – draw on the African-American lyrics and music of spirituals, blues, jazz, soul, and rap to engage and understand your own heartbreaks. African-Americans have done the bulk of the emotional work of our country for too long. Over the last few weeks, as our country increasingly convulsed with pain and protest, the rest of us are beginning to pick up our share of the emotional work, our share of the effects of the emotional violence of racism and anti-Blackness. This isn’t just about empathy from the outside – often forms of what Dr. Kenneth Hardy calls “privempathy” – but eventually about learning to feel that wherever you are in a system that breaks someone’s heart, tending to their heartbreak means recognizing your own broken heart, the irrevocable break in who you are, and learning to love, and protest (and make policy changes! and change our culture in fundamental ways!) with that broken heart. [ADDED NOTE: I was corrected by a reader: “privempathy” as referred to above is not merely empathy from the outside but is the “hijacking” of the experience of an African-American by empathizing through one’s own (privileged) experience of some form of hurt/subjugation. The notion of “privempathy” is described in this summary of Dr. Kenneth Hardy’s very compelling, and challenging, approach to cross-racial work. In some ways, the generalization of broken heart work in this paragraph may be interpreted as a kind of privempathy. Please see the end of this blog piece for a longer/larger clarification of what I mean as I call for this 'broken heart' work around anti-Black racism in our country.] Broken heart is a beginning. For Zen and Leonard Cohen fans, it’s the crack that lets in the light. A week or so ago, I wrote to a colleague, someone I don’t know well, about my (and shared) anger and heartbreak. I added an apology in case he felt I was overstepping into the personal. He wrote back that “reaching out with a loving heart is never overstepping.” When I recounted this exchange to another colleague and dear, dear friend, he commented that this exchange illustrated stepping into being vulnerable with a broken heart and open with a loving heart. This isn’t easy and often I feel foolish, and sometimes I’m told I’m foolish, or even downright wrong, directly or indirectly. If you have read thus far, some of you are probably saying, yeah, yeah, but what do we DO?!! I do believe that soulwork is essential, but as Audre Lorde said to her African-American sisters: “And political work will not save our souls, no matter how correct and necessary that work is. Yet it is true that without political work we cannot hope to survive long enough to effect any change.” She made that call to her sisters in the early eighties. Now in 2020, I say to my fellow Americans who are not African-American, while political work will not save our souls as Americans, extensive political work is needed to keep African-Americans alive and have equal access to good health and opportunity for “the pursuit of happiness.” Even today, June 10, 2020, African-Americans routinely face systemic inequity in education and healthcare, and discrimination in work places and public areas. They face very significantly disproportionate risk of death and indignity at the hands of police as well as non-police community members, and historically such acts of physical and emotional violence have tended to go unpunished or minimally chastised. The protests after the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, which followed the stark demonstration of structural inequality in COVID19-stricken New York, suggest that we may have come to a major turning point. Some of my thoughts on what is to be DONE are below, but first a note addressed to immigrants of color like me. This blog piece is written for all non-African-American citizens of the United States, but here are a few words for immigrants like me who are not white. While we may have our own experiences with racism and colorism both within and among us, and as we engage with fellow Americans, we also own the history of anti-Blackness and racism towards African-Americans. That racism and anti-Blackness is deeply our heritage as Americans. As my niece Mallika Roy taught me, we can’t just assimilate to some form of “white privilege,” or appropriate the African-American experience of racism as our own, or just sit out of this enormous political, cultural, social, and economic question that dates back to the earliest years of our country. To get us started, here is a great letter written by Asian American children to their parents four years ago, in 2016. So, now, some thoughts on what is to be done: -- Speak up -- VOTE!

-- Support activism and campaigns to change policies, government apparatus, and political leadership to

-- Pay attention to inclusion and exclusion, both implicit and explicit, in your workplaces and communities.

-- Do soulwork to understand better what African-Americans have suffered, learned, and given to the world; and to examine your role (you, yourself, as well as the you that lives out of complex and long-developing heritages). Carry some of the burden of the emotional work related to the physical and emotional violence of racism and anti-Blackness that African-Americans have carried for generations.

-- Don’t run away. It’s hard to live with what you can’t solve and with the pain of inequality, the pain of your own privilege and someone else’s suffering, to live with a seeping guilt (avoid that!) of your heritage(s). But, really, don’t run away! -- In the end, be guided by the excellent three steps offered by Maria Ressa, a journalist from the Philippines, in the graduation speech she gave in May 2020.

Acknowledgements: If you know me you have probably shaped what I’ve written here and/or heard some versions of this. If you see yourself in this piece, you probably are in it, even if I haven’t named you explicitly. That said, I started on this path most consciously in San Diego where there are particular people who have guided and pushed me in extraordinary ways. These include: friends and colleagues among the organizers, faculty and fellows of RISE San Diego’s Urban Leadership Fellows Program particularly in 2018 when I was on the faculty; staff and members of USD’s group relations conferences, particularly of the On the Matter of Black Lives conference held in March 2017; and finally words aren’t enough to acknowledge the guidance, patience, knowledge, and loving hearts of my dear, dear friends Zachary Gabriel Green and Cheryl Getz, and also Henry Wallace Pugh who has stood beside Cheryl for as long as I’ve known her. Of course, that doesn’t mean they would endorse what I have written here. These are people I have grown to love, which is the full face of gratitude, but I am still learning, still making mistakes, still working through my own cluelessness. _____ * The NYT is still figuring out what it wants to be in the 21st Century, as we fell into a Trumpian age that I hope we are clambering out of now. The NYT is not alone in this, but as one of the most prominent news organizations in the world, its spinning across torment, sentimentality, overwrought opinion, (rarely) humble offering of information, portentous screeds, and occasional brilliance affect us all. After all they are not a blog! And yet I read and learn from their articles. In many ways they represent and express a swath of our zeitgeist. ** This is a good time to acknowledge that I use the word American as the most quick and convenient designation for those who seek the benefits of, and carry accountability for, being citizens of the Unites States of America and as an adjective pertaining to their lives, activities, and creations, but I am aware that in the context of US domination in the Americas, “Americans” may intone and express a sense of US hegemony in our hemisphere. *** I learned the word “soulwork” also from thandiwe when she referred to the work – “soulwork” – of the Eikenberg Academy founded and directed by Dr. Kenneth Hardy. The word may have a longer history, but I learnt it from thandiwe and Eikenberg. I receive it as an evocative word for emotional work that goes deeply into what it means to be human, filling out and beyond, with great beauty and expansiveness, the more standard “life of the mind” that tends to get foregrounded in the “Western” (“white” or Euro-American) traditions. **** I haven’t written about influential African-Americans in sports because I don’t watch or follow any sport, and don’t really know enough about any particular person in sports. Note of clarification added June 17, 2020: A question from a friend who read this post led me to write this clarification. There are two pieces to this clarification. First, while it is written for anyone interested in reading some of my (still learning/still developing!) understanding of anti-Black racism in the United States and what needs to be done now, it is addressed primarily to non-African-American citizens of the US. Secondly, and very importantly, African-Americans don’t need to be aware of broken hearts and loving this country with a broken heart. They know this already! Their hearts have been broken over and over and over again for more than three centuries. And yet in 1955, James Baldwin wrote in Notes of a Native Son, “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Then in 1984 he had the following exchange with an interviewer for The Paris Review. INTERVIEWER “Essentially, America has not changed that much,” you told the New York Times when Just Above My Head was being published. Have you? BALDWIN In some ways I’ve changed precisely because America has not. I’ve been forced to change in some ways. I had a certain expectation for my country years ago, which I know I don’t have now. INTERVIEWER Yes, before 1968, you said, “I love America.” BALDWIN Long before then. I still do, though that feeling has changed in the face of it. I think that it is a spiritual disaster to pretend that one doesn’t love one’s country. You may disapprove of it, you may be forced to leave it, you may live your whole life as a battle, yet I don’t think you can escape it. These thoughts and sentiments have been expressed in word and action by many, many other African-Americans. So, no, African-Americans don’t need to be aware of broken hearts and loving this country with a broken heart. They know this already. It’s the rest of us (not Native Americans, who suffered violence and dispossession in the founding of this country, and who like African Americans have carried the burden of that emotional and physical violence) who might want to consider how we, as Americans, are broken. That, yes, we aspire to “land of the free,” AND that that aspiration also is based on a history of cruel dispossession and violence. This is not work for African-Americans to do nor do they need or want to help us do this work. This is our work, the rest of us, most of all white/Euro-Americans, but the rest of us as well. What African-Americans do need and want is for us to make our American culture and institutions less life-threatening and blocking to them. This is not about being sorry for African-Americans; they do not want or need us to be sorry for them. A couple of days ago, Imani Perry wrote a powerful and beautiful article in The Atlantic on this. Do read it. So then, what do we do with being aware of our brokenness as Americans? I don’t know. We’ll live some answers and then modify them as we see the effects of those answers. I think if we are more consciously aware of our brokenness – which cannot be erased, which is a core part of our history as citizens of the United States – we will shift our culture and institutions from the systemic injustices that arose from our violent history and we will love ourselves and others more fully. If you doubt love has anything to do with this, here’s something that James Baldwin wrote: “Love does not begin and end the way we seem to think it does. Love is a battle, love is a war; love is a growing up.” —from Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son (1961) Read James Baldwin, if you haven’t already. Every time I read James Baldwin I learn something about myself and the world. The focus on emotional and physical violence against African-Americans does not mean that other forms of discrimination, exploitation, and injustice don’t exist, or that economic systems don’t exacerbate climate change with all the effects it will have on vulnerable populations and ecosystems worldwide. I believe, though, that not only is eliminating the gross perniciousness of anti-Black violence way overdue, these various areas of systemic dysfunction are connected, and anti-Blackness is both a foundational element and one of the most terrible manifestations of linked injustices that have built up worldwide over centuries. I believe the building of concerted awareness and action against systemic anti-Blackness will vitalize other critical movements for change. A month ago, as we were told to retreat from public life in NYC, I found people, including me, staying out more widely and gathering more, and more densely, than the warnings called for. Then slowly New Yorkers, including me, retreated to our neighborhoods and then to our homes. As we did this, as an individual I worried specifically about loved ones and more abstractly about the scale and effects of this impending cataclysm. My family and loved ones live on several continents, some of us alone. I live alone. Like many other people I’ve learned to increase my use of messaging, phone, and video for mutual care with family and friends. Some people living alone feel lonely. I have a very high tolerance, and even need, for solitude, so mostly I don’t feel lonely, but the current form of my solitude – distant, with no physical activity of care for others – is also a building block for my bubble. In contrast to my situation, some people and families, especially in the small apartments of my city, contend with the everyday struggles of being constantly closed-in and crowded in small spaces. I live in West Harlem in Manhattan. My neighbors are primarily Latino and African-American. My own coloring is just about halfway on the range you see in my community. I’ve lived here almost two years now. From the beginning I’ve loved that people commonly speak to me in Spanish, at least until they see my goat-in-headlights expression. Before COVID19 lots of social life in my neighborhood happened in public spaces. Groups of all ages, but especially older men, and sometimes older women, would gather on or around a few chairs on the wide sidewalks of Broadway or on the small patches of green in the neighborhood; or they would gather on and around the benches on the divider between the two sides of Broadway. It was common to hear music, usually with an African-American or Caribbean rhythm. Quite elderly people – some disabled – were given place and engaged with in these public spaces. This was not some idyllic world. Most people looked worn. Many looked busy. Some frowned. Many looked intent, even worried. But I noticed and loved how familiarity gathered among people who live and work here and slowly I started feeling allowed to join in that gathering of familiarity. I have never felt unsafe in my neighborhood, even returning home on foot or by bus or subway after midnight. As COVID19 became more clearly, more palpably, a threat, we were told to stay home except for essential services (health care workers, transit workers, EMT and FDNY, police, grocery store workers, pharmacy workers, postal workers, trash collectors, and so on) and essential activities (grocery and pharmacy shopping, exercise). At first my neighborhood seemed barely changed. The old men continued sitting in their chairs and chatting, the young men played basketball at the recreation park not far from my home. For the first few days the sidewalks did not look hugely different from pre-COVID19 days. Slowly that changed. People continue walking up and down my street, but fewer, with more distance, and increasingly with masks on. People go to laundromats, people need to get food, people need to get away from crowded homes, and people – essential workers – go to work. Over the last few weeks most of what I see is from my closed second-floor window (it’s still cold in NYC) or on my walks to the grocery store or post box, or to the river for fresh air, beauty, and also to be with people though we keep our distance. Last Saturday, a young man, a stranger, delivered our mail. Our usual mail carrier is a young African-American woman who was assigned this route (to her delight, she told me) about the same time I moved in. I started wondering why this man delivered the mail and when I saw her again a few days later on my way to the river, I exploded at her with relief (from a distance). She had taken the day off to be with her children and family. So what am I doing behind my closed window, apart from looking at my neighbors walking up and down my street and clapping at 7 pm? Lots of phone calls to people around the world who are concerned about me, and whom I’m concerned about. I speak to my mother in India every afternoon. Almost every day I have contact with each of my grown children who are making their own adjustments to living with COVID19. All my consulting work in conflict resolution and leadership development – in any case no longer my primary occupation – is on hold. My primary occupation is writing fiction. I am trying to get my first two novels published, and have been reading in what I considered my fallow time before I start my next novel. Often I veer off to read and watch the news, including NY Governor Cuomo’s press briefings. A few times a day I get mired in my Twitter feed. Mostly my engagement with news and Twitter is a kind of frantic spectatorship. I look for places to donate to and donate, both to organizations that will provide resources to those most hurt and political campaigns of people whose values I support. Because of my recent divorce, I have some money I can invest so I watch the stock market, somewhat bemused. A faint guilt permeates the time spent watching the stock market and remains under the surface. Then I tell myself, better me than those hedge funds and rich people. But the faint guilt remains. I rule out certain industries and companies. But the faint guilt remains. We are all complicit in the economy. Some have less choice. Some have less effect. Some gain. Some suffer a lot more. Some don’t care. The faint guilt remains. Starting a month or two before COVID19 affected me directly, I've noticed a storm gathering within me regarding my third novel. In the greater solitude of this stay-at-home time the storm signs have become more urgent and I’ve been trying to figure out whether it’s time to chase that storm, and, if so, where to get close to it, how to engage with it. It’s a very large storm that’s been gathering, about all of life, which means life all the way from the quivering inside from where we are subjects, objects, heroes of our destiny, and beaten down. I’ve loaded my jeep and I’ve started out to chase this storm. Meanwhile, in numerous phone calls and messages I’m asked, “How are you? How are you in NYC?” Friends and family worry about me and they see me as touching, directly, the frightening tragedy they read about in their news media and see on their televisions. Inarticulately I tell them, I’m in a bubble. I feel like I’m living in a bubble, I say. I feel like I’m living in a bubble in a location of immense fear and distress. That’s all I’ve been able to say. I haven’t been able to, I can’t, claim more than that. Concurrently my internal storm is getting larger and more compelling. I’m closer to it. I’m ready to start writing again. Then, in the last few days, two things struck my bubble. Not bursting it, mind you; this isn’t a heroic story. A friend who works with very low-income women and girls in Kolkata sent me The Guardian article called A Tale of Two New Yorks. Yup, I know this, there is no hiding was my external response. Yup, we can’t hide from this anymore was my internal response, with a distant cynicism about what we can hide from given a little time and self-serving distraction. I turned to follow my internal storm. The second thing was my experience at an open mic program organized a couple of evenings ago (April 10) by Under the Volcano, a superb international writing workshop program in Tepoztlan, Mexico which I had attended in 2018. When the announcement and invitation to sign up arrived in my inbox, I immediately responded and got a spot. In Tepoztlan, two years ago I did my first open mic reading; I chose an excerpt from my first novel, narrating the main character’s frenzied turning inside out while painting. At that time I was in the beginning stages of my second novel, so for April 10’s open mic I decided to read an excerpt from my second novel which is about memory, identity, and the internet. The novel is also about love, anger, and difference, but for my three-minute slot I chose a piece that is rollickingly about coding, gaming, hacking, and AI. I love that piece, I still do. But when I heard a young woman in the Bronx read her piece I hit my bubble. Inside, outside, all of me hit my bubble. In and after a texting exchange with another participant after the open mic program, I continued to bounce in and off my bubble. Then, yesterday, another friend sent me the same Guardian article referenced above. With the repetition and given my experience at the UTV open mic, just knowing that two New Yorks exist, already knowing, did not exhaust my internal or external response. I immediately wrote the paragraph below and sent it to the friend who’d just sent me the article and a few others. This is at the core of my bubble: “The public advocate pointed out that 79% of New York’s frontline workers – nurses, subway staff, sanitation workers, van drivers, grocery cashiers – are African American or Latino. While those city dwellers who have the luxury to do so are in lockdown in their homes, these communities have no choice but to put themselves in harm’s way every day.” I see that every day in my neighborhood. I know that my going out won’t help, in fact by increasing density will raise risk for everyone. So I stay home, doing work nonessential for my city in crisis, in many ways unconnected to my city in crisis, in some ways – if I gain from that benighted stock market – gaining, how can that be possible, gaining while my city is in crisis. The question is how do I connect my work, my living with this reality: how do I connect life inside me – that storm gathering – with life outside me? This blog post is one start to addressing that last question, amplifying the question, looking at how it rises both outside and inside me. I do not touch the distress of my city directly, but, in my bubble, I am part of it. This is not an ending. There is no resolution here. The inequities that exacerbated the unevenness of tragedy in my city existed before COVID19. The communities that have been asymmetrically affected by illness and death are likely also to be least helped by recovery efforts, least strengthened for the longer term. I can’t just be appalled. I can’t forget. This is a long game, not a short-term wringing of hands. Added perspective: This blog post focuses on my bubble in NYC where I live, but the bubble phenomenon is countrywide, worldwide. In the U.S., race and color add an enormous burden, but low-income people everywhere serve more and are served much, much less. Added comment: This was a difficult piece to write. It’s hard to reveal privilege even to myself, because a significant amount of privilege is unfair; I want to be “good.” But it’s much, much harder to live (and die! to see your loved ones die) without genuine equality of opportunity, equality of access to wellbeing, and equality of access to community resources in times of need. When I was young, I often fought for fairness, but I learnt slowly that life, often enough, is “unfair.” Getting old, I know life is “unfair,” but I’m learning that if I cut myself off from directly engaging with life outside me, I become emptier inside. In my case, directly engaging with life outside me means not turning away from being appalled by unfairness that I’ve always known; from my own confusions, complicities, and complexities; and from attentively, cannily choosing fairness and equity more and more rather than less. In practical terms, the last means supporting adequate wages and income security for minimum wage/hourly/casual/gig workers; easy access to health care information and services, including health insurance that is affordable or free where needed, but also specific systems in place for outreach, health education, and diagnostic and preventive services; attention to environmental health hazards, including housing deficiencies, work conditions, and inordinate production and marketing of junk foods; equality of opportunity in education which means explicitly lots more effort for children who don’t grow up with income-/class-based access and exposure outside of school systems. These are obvious ongoing things. Crises will come again; climate change is looming. In crises, the first question must be: what extra attention must we pay, what extra must we do to protect people with the fewest resources, in places with the fewest resources, who are often also most at risk? We must be prepared for this question, that extra. In a crisis we are all appalled. When this is over, how will I continue? How will you? Two weeks ago, a companion called Leah Goodwin taught me and others a mysterious healing process. Mysterious to me, that is, probably not mysterious to its practitioners, whether in Hawaii, its original home, or elsewhere. According to Leah’s teaching, a therapist heard that a healer cured a group of unhappy people, with bewildered minds, without using drugs or psychotherapy. The process has a name that sounds silly to me – ho’oponopono. The therapist, Dr. Ihaleakala Hew Len, tried it out, found it worked, and passed it on, as Leah did.

When Leah talked us through the process, I found myself sandwiched between tenderness and embarrassment. Used correctly, it calls for complete and ridiculous openness. Nobody could, or should, be open like that, not even a child, I thought. But when Leah taught this, I was with a group of people I’ve grown to love and trust. I stood in the shadow of friends who knew I was a fool and somehow found me wise. With them I could be that open, that ridiculous. Ho’oponopono involves the incantation, with conscious and deep intention, of four sentences to oneself, or to another, preferably both (and, if both, that means all). The sentences, Leah told us, could be in any order. She has a preferred order, but any order is fine, so long as all four sentences are understood, spoken, and intended. These sentences sounded moving and profound, even divine, among these friends I trusted and who learned this process with me. Imagined beyond this group, they seemed frightening. They risked giving away too much, I could lose myself. If they were not matched, I could be reduced to a sentimental puddle – abject, without definition – and forever depleted. So what, already, is this incantation?! What are these sentences? I’m sorry. Forgive me. Thank you. I love you. As I quickly typed these sentences, then hurry my eyes away from them to these words here, I think, gosh, if Kavanaugh said these. Of course, I don’t want him to, because that would make him pretty amazing – what were those words I used? moving and profound, even divine – though conservative. His saying these sentences would challenge us on the political left to take “compassionate conservatism” seriously, to consider saying these sentences to conservatives. But, ha, ha, he is far from saying it and, from where I sit, conservatism still looks rather un-compassionate. In case you (meaning I) need reminding, I still don’t like him and I still want to work for change in the 2018 mid-terms. Rationally, truly, ho’oponopono has its limits. Dragging the process beyond these limits can be dangerous. In some ways, best to forget all about it. But I shan’t, because ho’oponopono is not about reducing myself and you and susceptible varieties of bleeding hearts to loving blobs without definition, difference, and conflict. Ho’oponopono is not about side-stepping definition, difference, and conflict. Ho'oponopono is being unafraid to love even where there is definition, difference, and conflict. It is trusting that I will not lose myself if I say I am sorry. It is trusting that gratitude/love/apology/forgiveness and accountability can co-exist. Indeed, gratitude/love/apology/forgiveness offered with the (embarrassingly!!!) open spirit of ho’oponopono, is a true invitation to accountability, to own all of yourself. Where ho’oponopono is most needed is where it is hardest. I can’t yet use it in my hardest places. Better to laugh. Better to scorn Kavanaugh. Best (more sneaky, more virtuous) to ruminate: if I think Kavanaugh should say I’m sorry Forgive me Thank you I love you … what would it mean for me to say to Kavanaugh I’m sorry Forgive me Thank you I love you ? And yet, today, with all the swirling ill-will that continues to surround and emanate from the Kavanaugh nomination, even this virtuous self-examination, this sneaky hypothetical, is walled up and dull. WARNING: If you have not read the book, there are spoilers in this review.

Like many cosmopolitan, post-colonial South Asians, Hari Kunzru writes extraordinarily well. He knows and loves words in the English language, not just the functional language of the British Islands, but the de-territorialized language of twentieth century globalism, kneaded by diaspora intelligentsia, whimsically dipping into the vernaculars and dialects of English-speaking localities, and – in Kunzru’s case – ironically, but also desperately-lovingly, seeking to use English, a language of modern power, as a moral language that mourns, assesses, and stays alive. In White Tears, he writes beautifully and he has a fabulous, intelligent, moving, and unusual concept. As an aside, but this is important, I came to the United States in 1980, a post-colonial Indian, fresh off the boat, not knowing the blues at all.* I’d heard jazz and rock, and, yes, I may have listened to Billie Holiday, but simply as jazz. I did not know the blues. In the early eighties, three young white people from North Carolina introduced me to the blues. A few years later, more white people introduced me to more blues. No African-American has introduced me to the blues, though one here, or one there, may have listened to a song with me. White Tears is about the blues. It is also about incarceration, racism, American government, guilt, and blaxploitation. I read it after J. Saunders Redding’s No Day of Triumph, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, also some Flannery O’Connor, but before Marilynne Robinson. This context is important because it reflects one thread of twenty-first century grappling with “race” in the United States: immigrants, especially non-white immigrants, consciously – intellectually and morally – adopting and owning the race history, and the racial present, of their new country, trying to find to find an American identity between, or beyond, the two easiest choices: “to assimilate into White culture or to appropriate Black culture.” ** The main characters of White Tears are two young white men and a vengeful black ghost. The two white men love music, particularly the blues, particularly the richer white man. The poorer man is adept with technology, the richer is a collector, and neither is good at navigating the moral delusions of human societies. Kunzru sets up a gorgeous plot device which begins with Seth’s hearing a song fragment while randomly recording street and other public sounds in New York City. It leads to a theft of intellectual property, of cultural property. We don’t know it, but the past is vengefully inserting itself into the present. We get a hint of mixed realities but the language of reality keeps us grounded in the present. The rich boy, Carter, gets beaten up and disappears into a coma, but we are not sure if all of that is real or a delusion. The remaining boy (Seth) knows that the attack on Carter has something to do with the theft of the song, but he believes that the threat will be dispelled if he can explain and prove the innocence of the prank. Meanwhile, he has geeky hots for Carter’s rich sister (Leonie), is conned by a journalist masquerading as a friend, and draws Leonie into the retracing of a tragically exploitative trip, during which she is pruriently murdered and he falls into his first full hallucination of white face-black face. From that point, the narrative spirals towards to the climactic integration of evil-innocence-cluelessness-privilege-death and subordination-suffering-incarceration-ghostsofChristmaspast. The problem with White Tears is it is not a tragedy. The bad people are unambiguously bad. Revenge is simple. The innocent are clueless, and cluelessness is not innocence. Kunzru’s story is very powerful, relating a national, indeed global, history of extreme exploitation, of capitalist and racist privilege, of systematic cruelty. This is a story of deep red and black strokes. The flaw in White Tears is that he tells it with deep red and black strokes, but he – diaspora brown, and post-colonial like me – does not have adequate color capacity for it. Coates tells it black and red, unrestrained, and sometimes tenderly, from his heart; he himself grows in the telling. Redding’s 1942 travel memoir is written with a post-War, pre-Civil Rights optimism. His telling is fluent and dispassionate, skillfully weaving literary English and the vernaculars of the southern localities he visited. With scholarly calm, Redding chronicles harsh and casual racism, and the human frailty of Southern Negroes (as they were called in the forties), whether beaten down by poverty and racism or, if well-off, struggling to reconcile racism and economic privilege. Americanah’s narrative goes from the ordinary color consciousness in a non-white, post-colonial, independent state – in this case Nigeria – to consciousness of racism in the United States, with a side journey into racism in England, and back to a twenty-first century globalized consciousness of race and color. Like Kunzru, Adichie writes with all of the skill and confidence of the educated post-colonial cosmopolitan. She claims all of the English language, and writing phenomenally, so to speak, claims all of the colors her novel can bear. She cheerfully presents us with types, and then just as exuberantly adds their ingrown hairs and pretensions. In the end, Coates, Redding, and Adichie write about flawed people loving, exploiting, or being clueless about flawed people. Held against them, albeit serendipitously, Kunzru writes about bad, or consciously false, people exploiting weak people. In White Tears, Hari Kunzru writes a superbly ambitious story. He manipulates structure, language, and plot both intriguingly and smoothly, and his characters are often perceptively drawn, although sometimes with more self-conscious irony than needed. However, in this brave effort to write about race in the United States without (simple) assimilation or (strident) appropriation, Kunzru loses his voice, and as a result no character is full, not as black, not as white, not as female, and not even as male (or other gender). The characters who are closest to being full are the two lonely older (white) men, JumpJim and Chester Bly who move through their ghostly parts in ways that are both lumpy and alive. They are not stock characters dressed up; they have shadows that allow me imagine into them. JumpJim shuffles and obfuscates in palpable ways while Chester Bly travels through the south like a lovingly-rapacious white doppelgänger of J. Saunders Redding. To the degree this review sounds critical, it is not about throwing shade on Kunzru for misappropriation nor is it calling on Kunzru to add a “brown” voice if writing about race in the United States. Rather it is a rumination on the difficulty of trying to write about race in the United States, where every word takes a stand and every word can be hurtful. One path to safety is to write what, at its fullest, is an uncontrolled narrative in a highly controlled way, where the writer is apart and in control always. The rub is that ‘to be in control always’ can only be achieved with a limited range of representations. This means that the writer risks being more on the mechanical end and less on the “live” – internally conscious, escaping, haphazard – end of narrative representation. As a South Asian diaspora voice, Kunzru writes very carefully about race in the United States. He is not afraid to personify the badness of racist capitalism and the will to vengeance of the historically exploited. But, in a curiously ironic way, while he makes the blues the heart of the story, he loses the pathos of the blues which is a human pathos. The whiteface-blackface-whiteface torment in Seth’s story comes the closest to pathos, but Seth loses palpability as his delusions are cleverly articulated. In the end, his delusions and hallucinations come across more as elaborately didactic representations of the delusions and hallucinations of racist capitalism than as human pathos that wends through will to/subordination to power, desire, suffering, love, weakness, and death, though not necessarily in that order. * For more on my slow, always incomplete, learning about race in the United States, see my blog post The Color of People. ** Mallika Roy, Hardly Un-American Depending on what the beholder chooses to emphasize, Emmanuel Macron looks a lot like Barack Obama, or looks vastly different from Barack Obama. Among the similarities: both the men started out as young upstart contenders for head of state of a powerful country; both have degrees from elite universities; both have a literary sensibility; both are comfortable with the globalist and tech-savvy zeitgeist of the 21st century; both have been deeply influenced by strong women in their lives; and both are socially progressive and economically centrist, or, for many critics, “neo-liberal.” The most notable difference is that Barack Obama, with an African parent, has a fundamental aspect of identity that is not aligned with the whiteness of the traditionally standard “American” of colonial America and the independent United States while Emmanuel Macron is gloriously standard white “French,” as he himself puts it “a child of provincial France.” One further difference, that is crucial though small, is that Obama’s course to politics took him through an intense phase of community organizing while Macron’s took him through successful international banking.

But why the comparison? Because there is one further, and major, similarity. Obama offered hope and optimism to the United States, in which a core population was beginning to express its growing disaffection with the inequalities of globalization. For all his successes, a substantial portion of this core population believed he failed them and their disappointment contributed to the election of Donald Trump. Like Obama, but at a later stage in the decline of the heartland industries of the West, Macron offers optimism to France. He is heard more skeptically than Obama was, in part because of the perceived failures of the last decade, in part because he is perceived to be aligned with globalized financial elites (no community organizing in his history, remember), in part because his political experience is much less than even Obama’s was, and in part because he does not have Obama’s oratorical skills. Now, in 2017, Macron may well become President of the Republic of France. In the last days before the first round of voting, he posted an amusing video on Twitter – a call from Barack Obama, who wished him well. In a significant way, Macron, if elected, will inherit or will have the opportunity to inherit, Obama’s mantle. If he becomes President, he will need to engage the deep reformism that Obama only partially engaged. With the world economy growing again, he will be both in a stronger position than Obama in 2008 and will face a real possibility of initiating the end of both the European Union and the Fifth Republic if he fails. Marine Le Pen’s gains on her father’s electoral successes, and her support from a large proportion of French youth (who face an unemployment rate above twenty percent), are striking and if a Macron Presidency is experienced as ineffective the next President of France might well be Le Pen. So what does effective mean in this context? It means reconciling the gains of 21st century globalism and technology – which are redefining culture and redistributing work – with a real renewal of “la France profonde,” not just as a relegated patrimony but as areas of restored economic activity and cultural relevance. It means harnessing the technological drivers of economic growth in the 21st century without losing a practical commitment to human dignity as a social value in itself. It means renewing the cultural centrality and economic viability of French autochthony and ethnic whiteness while integrating the colors and cultures of non-white French communities. It means domestic transformation while managing the constant encroachments of a complicated world: a flawed European Union and euro zone; murderous acts committed by militants, including French citizens, who call themselves Muslim; a Russia that seems to want to return to world power status through covert activities as well as alliances with alt-right groups; a global economy that is decentralized and nimble; and a planetary ecosystem that is in great danger. Does Macron have the ability to be bold, to listen, to build alliances across political boundaries internally and externally, to identify core purposes and remain steadfast when he, inevitably, faces opposition and failures? For that is what it will take. Obama had the same opportunity, along with the complications that were particular to the time and place of his Presidency. Macron, if elected, will lead a new round of a fateful and sensitive experiment: can the paradigm shifts propelled by economic globalization, technology, demographic changes, and climate change be reconciled, peacefully and productively, with the affect of deep-rooted national identity that is correlated with white-European ethnicity that has enjoyed a seven-hundred-year ascent to geopolitical dominance but is now on the decline? Or is violence – whether direct or hidden, whether to protect or to exclude – inevitable? Note: This piece was written on 4/26/2017. On May 4, 2017, a video endorsement of Emmanuel Macron by Barack Obama was made public. In the spring of 2012, I watched The Hunger Games. I was horrified by the story. I hadn’t read the books, though my daughter and nephew and millions of others had. I knew it had a strong female hero and so I expected to like it. But then I found that the core story involves a gladiatorial competition between children, where the winner is the one who survives. The weak, usually the youngest, get picked off first. What mind conceived of this horribly implausible game, I wondered. Never in history, to my knowledge, had any ruler or regime instituted such an entertainment. Yes, children were wantonly killed; yes, people were killed by (adult) gladiators; yes, child soldiers killed and committed atrocities in a “war.” But this pitting of children against children for entertainment made no sense, fit no pattern that I could think of, though it was a compelling story to follow and watch, much like a horror film. It wasn’t implausible in the way a superhero movie with bogus science is implausible, it was implausible because the social premises seemed off.

The only way it made sense was as an allegory. I moved back from the immediate spectacle of bigger children killing smaller children in a lush game world and considered only the most basic scaffolding. The story is set in the country/world of Panem which has twelve districts surrounding the capital. The districts are punished annually for a long-past insurrection by having to give up a child to fight in the Hunger Games. The capital is a beautiful city with wondrous technology, extravagant foods, fascinating clothing. All in all it expresses a climactic moment in human design and artifice. The richer districts are close to the capital and the poorest is far away. Typically, the expectation is that a child from the richer districts, usually one of the older children in the competition, will win (killing or otherwise out-surviving the others). So, with what framing could I find children surviving by killing or out-surviving other children plausible? Looking at the structures of my life, I am close to the centers of power and wealth, not geographically but in class terms. I enjoy some of the ease and luxuries that are increasingly taken for granted, and often further rarified, in those centers. My children have tremendous access to opportunities of various kinds. No, of course, they aren’t like the competitors of The Hunger Games, my mind shies away from the thought, but out there are children, even in the US, who have much less, and further out there are millions of children among the 20 million people who are at risk of starvation, right now in 2017. Our children do not choose these roles. It is as adults that we acquiesce to these structures, with those of us who are closest to the centers of power and privilege acquiescing the most. It’s very difficult not to acquiesce as an individual. The system supports, and is supported by, a web of daily tasks and pleasures. I could pay more taxes. I could give more money to worthy organizations. I could work in public service jobs. I could volunteer. In all these cases, my individual actions can easily be lost or get wrapped into the same-old. It’s not just a case of feeding the twenty million enough that their dead bodies don’t saturate our newsfeeds; and, then, once this crisis is past, we would leave them to a deprivation that is one notch above death. As an allegory, a plausible one it turns out, The Hunger Games helps us see the problem in our own lives, but it doesn’t help us much with a solution. In Collins’ trilogy, Panem’s socio-political structure is maintained with hidden (and not so hidden) violence and trauma, and then is, itself, overturned with extraordinary violence and trauma. We have our own hidden, and not so hidden, violence. But I cannot hope for the extraordinary violence that drove change in Panem. So, in the dull way of ordinary work and long-term trajectories – not just of policies and numbers, but also of relationships and accountability – how do we, in the US, look past one or two elections (2018! 2020!) to a larger, longer-term shift from the inequalities and hidden (and not so hidden) violence of our world? How do we work for this shift across political boundaries? Or can we hope only to hold back the worst extremes? Twenty million people are facing famine now. The US media has had an exciting year. They got to cover one of the most polarized, intoxicating, and prurient of Presidential elections ever. Everyone weighed in, all the mushrooming online outlets, the traditional paper press turned online, and television. They had a photogenic – albeit mostly in a funny way – candidate and a candidate whose stolidity, some surmised, could only hide layers of Machiavellian ambition. With very high stakes and appalling new twists every few days, the relevance of and popular addiction to news spiked. As boundaries between commentary and reporting blurred, readers and watchers often found opinion crowding out information.

Already in the months before the November election, the press started getting criticism, from across the political spectrum, for editorial bias, too much false equivalency, focusing too much on relatively trivial issues, and too little on important issues of policy; for simplistically reflecting and stoking drama, mudslinging, and divisiveness; and, yes, for offering entertainment and opinion more than analysis with enough of the data and logical structure revealed to allow the reader, or watcher, to explore the plausibility of conclusions other than that of the writer or speaker. After the election, the criticisms continued, with the added critique that the mainstream press was too slow to recognize and counter the spread and effects of “false news.” The press has engaged with some of the wide-ranging critique, most often acknowledging that there were important trends that they missed, but also defending their editorial choices, including the choice to prioritize opinion even in “news” articles. On December 8, 2016, the New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet was interviewed on National Public Radio. Terry Gross, the interviewer, read a letter to the NYT by a David Langford, who expressed dismay at the “continuing blurring between editorial commentary and news coverage. In another age, the word ‘baseless’ in your front-page headline would have been reserved for the editorial page where it belongs. The Times and other news organizations should resist the temptation to… drop their conclusion into news stories. Please allow me, the reader, to draw a conclusion for myself.” In his response, Baquet chose to defend the use of “powerful language,” side-stepping the larger question of opinion dominating information in news stories. As Baquet acknowledged – “I’ve said this to a lot of readers,” he said in the opening sentence of his response – there are a lot of people out there who are frustrated about opinion-creep in the US news media, and not just in the NYT. The media are not helped by the President-elect’s orientation to information. Mr. Trump blurs information, probability, investigation, wishful thinking, and certainty in idiosyncratic and alarming ways. A case in point is the current issue of the degree and intentionality of Russian hacking and influence in the recent Presidential election. On October 7, James Clapper, Director of National Intelligence who leads the 17 US intelligence agencies and Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson issued a joint statement that the US intelligence community “is confident that the Russian Government directed the recent compromises of e-mails from U.S. persons and institutions, including from U.S. political organizations…. [And,] based on the scope and sensitivity of these efforts, that only Russia’s senior-most officials could have authorized these activities.” The Trump campaign dismissed that statement. More recently, the CIA has offered the stronger view that the Russian government aimed to promote the election of Mr. Trump. Mr. Obama has instituted a deeper investigation, in which he is supported by various Democratic lawmakers as well as a few Republican lawmakers, most notably John McCain and Lindsay Graham both on the Senate Armed Services Committee. In a small side-twist, the FBI, while not denying that the hacking was directed from Russia, is hesitant to attribute intention to favor Mr. Trump. Meanwhile, Mr. Trump has rejected the conclusions of the intelligence agencies he will lead as President of the United States and on December 11, 2016, in a Fox News interview, Mr. Trump said about the intelligence reports on Russian hacking that “It’s ridiculous…. I don’t believe it.” This is not, “I have questions, it is under investigation, we still need more evidence,” or anything like that, it is bluntly, “I don’t believe it.” So in an environment in which the media are already tending towards information-light and opinion-heavy reporting, the press is charged with covering a President-elect who has taken the prioritizing of opinion, in this case his own, to a whole new level. If information and logic are minimized to “I don’t believe it,” and “wrong” by the highest executive authority in the country, it leaves the press running behind, trying to substantiate, confirm, and correct as necessary. If in that effort to play its role of “watchdog of democracy,” the press counters OPINION with opinions, it will leave us in the electorate less and less informed and thus render our democracy more fragile. Over the last two decades, the press has had to adjust to the speed of aggregation, low barriers to spin-off articles, and overall pressure to update news rapidly, while revenues have fallen, resources and time for fact-checking, writing and editing have become tighter, and there is always someone ready to draw away your readers and audience with something – usually opinion, preferably polemical and polarizing – that is more entertaining. On October 14, 2016, Matt Taibbi, a superb writer for RollingStone, wrote a very clever and opinionated article on “The Fury and Failure of Donald Trump” in which he pointed out that the Presidential election campaigns were being run and presented as a “Campaign Reality Show” and the effect was “to reduce political thought to a simple binary choice.” When asked on Twitter what the role of the press has been and can be in relation to this “Campaign Reality Show,” he responded, “ It’s hard. The reality show format is too profitable for MSM [the mainstream media] to give up. The actors are not only unpaid, they pay us (in ads)!” The US media must do better than that. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed