|

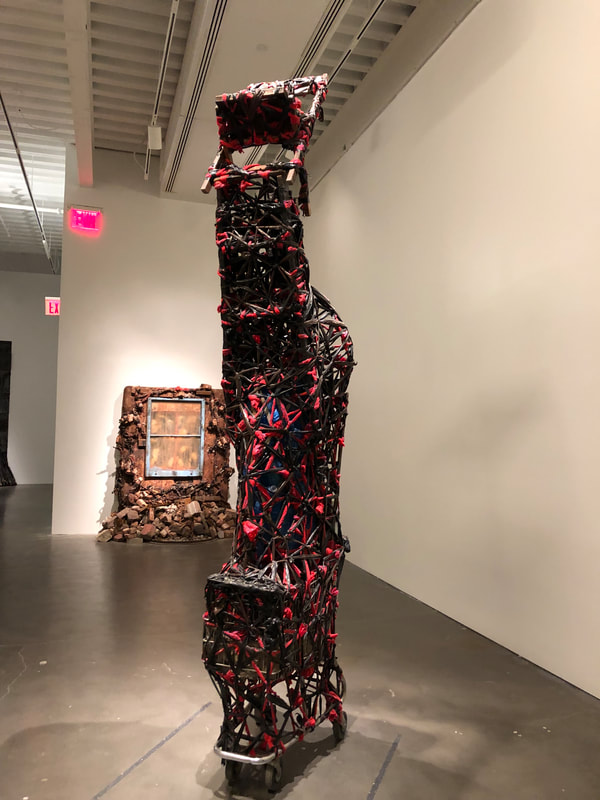

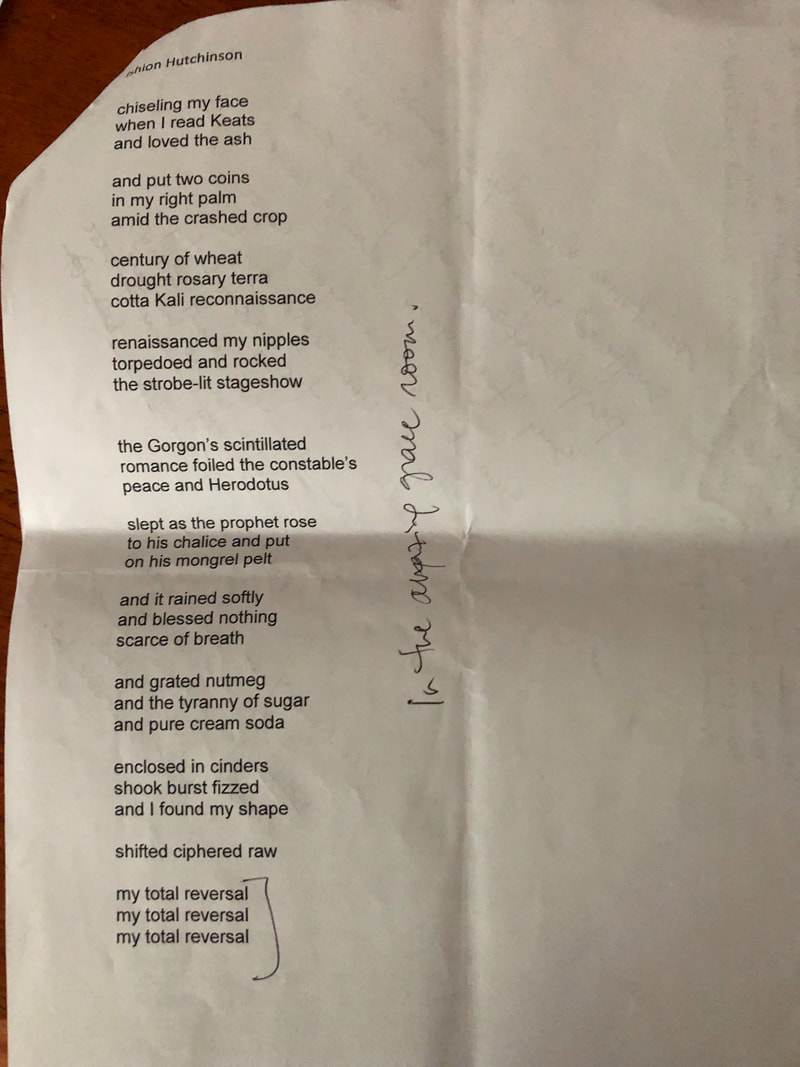

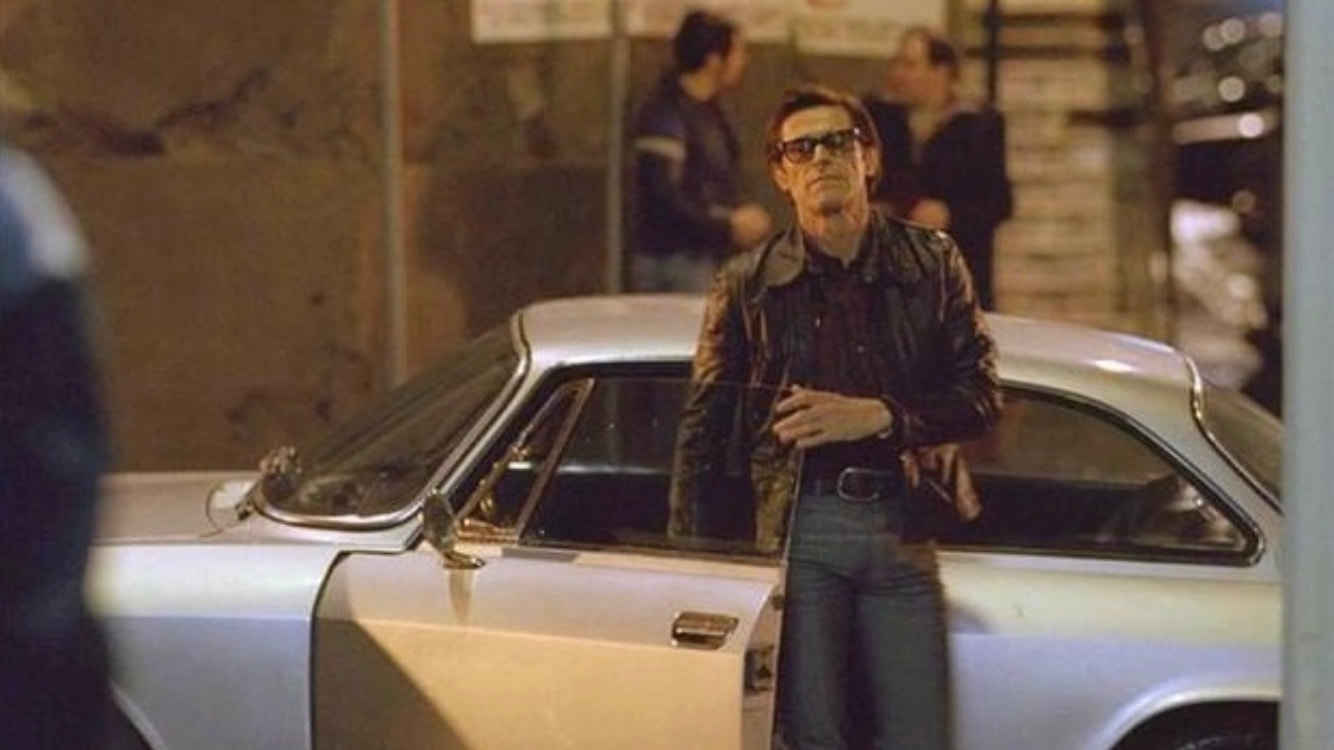

(Spoiler alert re the movie Pasolini) The sequence of Nari Ward, Ishion Hutchinson, and Pasolini just happened; there was no plan on my part. Nari Ward and Ishion Hutchinson were paired by the New Museum. Not unexpectedly, they were a good pair, or rather I found Hutchinson’s response to Ward’s art provided something like a blended glass, part mirror, part filter. More about that in a bit. I added Pasolini because I wanted to use my Metrograph membership; I could walk to The Metrograph from The New Museum, and Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini was playing at the right time for me to move in this way through the city. Interestingly, going to Pasolini also became the right movement for a kind of intellectual and emotional trajectory. Though this is often the case as we knit the past into some kind of coherence, in this case I struggled with making the sequence coherent, then forced a coherence, and then was struck by what came of and from the forced coherence. I went to The New Museum for the first time about two weeks ago because a friend wanted to go there and I’ve wanted to go there for a long time. We started on the top floor with Jeffrey Gibson’s kaleidoscopic work and I passed through his work, loving the color and the immanence of movement. Later, I passed through Hélène Cixous’ odd, insightful, and romantic essay on Gibson’s work. “A dislocation is at work,” she wrote. Then we went down three floors of Ward’s large installations and smaller, more compact, art in the exhibition called “We the People.” The making of art from found objects is not new but the poignancy of this exhibition lay in the bend between the mourning of pain and history, and the fertility and beauty of, somehow, life. I had not heard of Nari Ward before this and got a little uncomfortable when I heard that he is a Harlem-based artist and his art connects directly to dispossession, not only of the past, but directly in the effects of gentrification in the present. I moved into West Harlem in June 2018, an innocuous, older-ing, and brown woman. I belong here, and I don’t. I had noticed, when checking out the museum before I went there with my friend, that Ishion Hutchinson was going to do a gallery talk on Nari Ward’s work. When I asked if there were still tickets available for that gallery talk, I was told there were. I was stunned. I guess this is NYC. I said, if you don’t think they’ll sell out while we, my friend and I, go through the exhibitions, I’ll wait to see Nari Ward’s work before buying a ticket for Hutchinson’s gallery talk. They assured me there would still be places, and there were, and once we’d walked through and down all the floors, I bought a ticket for the talk. So, on Thursday, May 16, my hair freshly colored, I went back to The New Museum, and waited for Ishion Hutchinson’s gallery talk. Ishion Hutchinson, like Nari Ward, is Jamaican-diaspora African-American. He is a poet I much admire. He took us, a group of about fifteen people, through parts of “We the People,” with eloquence, diffidence, clarity, and kindness. He took us – none of us belonging to the African diaspora, though all of us share fraught histories with Nari Ward and him – through touching what ‘fugitive’ can mean in history, selfhood and art; through hearing the grandness of aspiration while living in “material fetishes of failed utopias;” through sensing, distantly – in our case, each of us, perhaps with some guilt, or shame, or desire – “an old resilience which is part of [Hutchinson’s] heritage.” He told us about the abeng, and made its sound with his breath, his throat, and his mouth – this was a generosity of sound, not just a performance or lecture – and related it to the artwork called Savior. The abeng, he told us, makes the sound of the fugitive. He lost his voice briefly after making that sound. He stood in front of the two pieces called Breathing Panel and, at the end of his prose response to the artwork, repeated, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe….” In that brightly-lit gallery, with chattering, whistling sounds from an adjoining artwork, with only one other African-American, a gallery attendant, in view, with one other gallery attendant who looked Latino, and me, a class- (and caste-) privileged South Asian-American, with everyone else phenotypically white, mostly women across a range of ages, I wondered who couldn’t breathe now, why couldn’t they breathe. Who is breathing? For how long? Then he took us to the large, dark room in which Amazing Grace was installed; “a womb, a slave ship, an ark,” he called it at the beginning and towards the end. He walked us, two-by-two and holding hands, through the stroller-ship-womb. He read his poem Sprawl and repeated “my total reversal” – the last three lines of the poem – more than three times. And then we were done. And I got him to sign my copy of House of Lords and Commons which he not just signed, but also inscribed with “a small, drifting raft” for me. I walked out into the sunny afternoon, exchanged cheery words with one of the outside guards, walked through Chinatown, got a text message from my daughters in which they laughed at my ‘culture-vulture’ day, got to The Metrograph, and bought a ticket to see Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini. On Instagram, I posted some pictures and wrote: it’s hard to call walking through Nari Ward’s work at The New Museum a pleasure, but perhaps one can call it a tenderness, an amazement at how beauty can come alongside, and from, ugliness and sorrow while underlying cruelty and pain remain cruelty and pain. Pasolini starts, if not right away then very early on, with explicit, aggressive, unlovely sodomizing of two submissive young women. With Pasolini, I seemed far from the fugitive grief and anger and grace of Ward’s work and Hutchinson’s words. There was abject or abjectify-ing sex, followed by ordinary domesticity and interesting, but cold, words. “Narrative art is dead,” Pasolini told us, “we are in mourning.” “Mine is not a tale, it is a parable,” he said, “I am a form, the knowledge of which is an illusion.” To Pasolini, it appears, I, Meenakshi, am a moralist, who neither seizes the right to scandalize nor feels pleasure from being scandalized. About a third through the movie, I wrote in my running notes: so far there is very little that one might call kindness, or love, or tenderness. I watched more sex -- this time apparently not abject or abjectifying, more a kind of revolutionary procreation in a reversal of desire -- between beautiful people, with a raucous audience within the film, and us, a quiet audience outside the film, with our own arousals and withdrawals. Pasolini sees his work as a revolution. “I’m asking you to look around,” he says, “and see the tragedy… … starting with universal education … which leads us to want … and not stop short of murder…. … an appalling tradition that is based on this idea of possessing and destroying.” * The tenderness came at the end of the movie, when Pasolini is beaten to death on an industrial beach and the movie closes with a “clip” from a made-up movie based on Pasolini’s last work-in-progress. In the clip, Epifanio, an older-ing man, and his young companion are trying to get to Paradise and Epifanio can’t go on, so the young man says, “The end doesn’t exist. So we just wait. Something will happen.” Obvious shades of Godot, but owned here in its own terms, with its own peculiar pathos. In the end, the tenderness comes from the unabashed living of, and looking at, life with all its ugliness, its earthiness, its longings, its sensuousness, its beauty of form and light and shadow, its flaws, and just life. In general, I prefer to look at, sense, and join joy and tenderness of a different kind, but I did feel the tenderness at the end of this movie. Then started the struggle of knitting the coherence of my past. In my head, I stared at the obvious challenges of colonialism, racialism, the cruelty and survival of color lines of history, simplistically pitted against normative sexualization, scandalous desire, the intense ambivalence – intimacy and violence – of sex, and the cruelty and survival of power lines of history and didn’t get far, actually didn’t get anywhere, so retreated to higher abstractions. This is what I found. In Pasolini, there is no redemption, no desire for redemption. There is (only?) a wild grasping for freedom outside a cruel system that must be broken. In Pasolini, to the degree there is redemption, redemption lies in the external viewing of a complex tale – not a parable – about an ambitious fragility, or a fragile ambition. In Ward’s work and in Hutchinson’s words, there is redemption. Pain is overcome – indeed redeemed – by creation, by making beauty and life, and, in flashes, love and joy, from the remains of things, bodies, words, feelings, life itself. In Ward’s and Hutchinson’s work, perpetrators are on the other side; Ward’s and Hutchinson’s focus is on fugitiveness and resilience (Hutchinson’s words). In Pasolini, there is nothing fugitive, no one hides (except, perhaps, one time in the movie when Pasolini evades his interviewer’s question about what would remain if Pasolini could magically wave away everything he opposes), apparently nothing is hidden, perpetration is right there in front of you, drawing you in, people are broken down, perpetration itself is broken down. From this forced coherence, I knitted an easy/uneasy synthesis. In the face of suffering, sometimes one wants to shove perpetration up front and say, “fuck you, I don’t care!” Other times, one holds on to beauty, to the possibility of beauty; you want to cry because you cannot but care. And, zooming out, a creation that expresses only one of these impulses will feel flat – just brutal, or just sentimental. I did not find Ward’s, Hutchinson’s, or Ferrara’s work flat. To close, in my way: when I first decided to write about my forced coherence, I didn’t plan to include Jeffrey Gibson’s art and Hélène Cixous’ writing. But, having written thus far, I want to end with Gibson’s resplendent art. That is also life. And Cixous wrote of his dolls, which did not figure in this current New Museum exhibition, “… these were his people, his heritage, his self-portraits. Beautiful dreams, realized, and guarding their secrets.”

*Note: I wrote these words in my running notes. I’m pretty certain all the words and the logic they convey are accurate, but I’m not so sure about the ellipses.

0 Comments

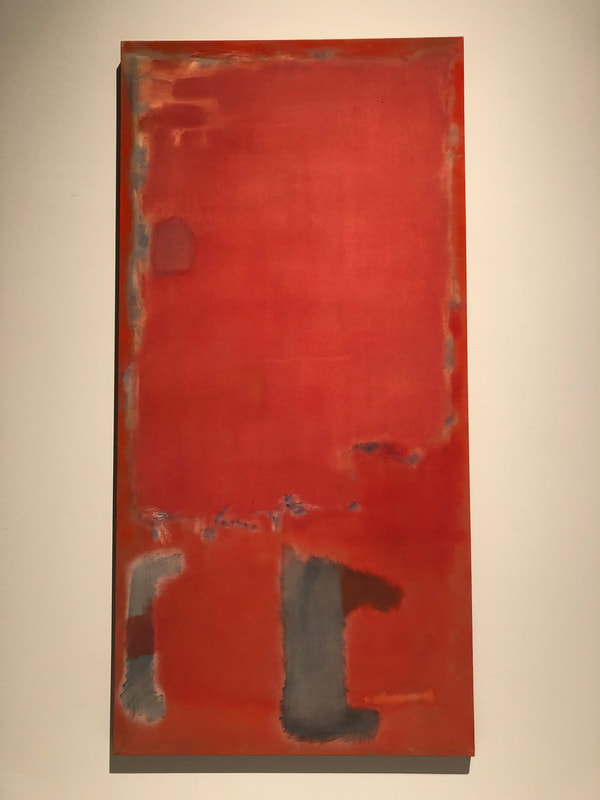

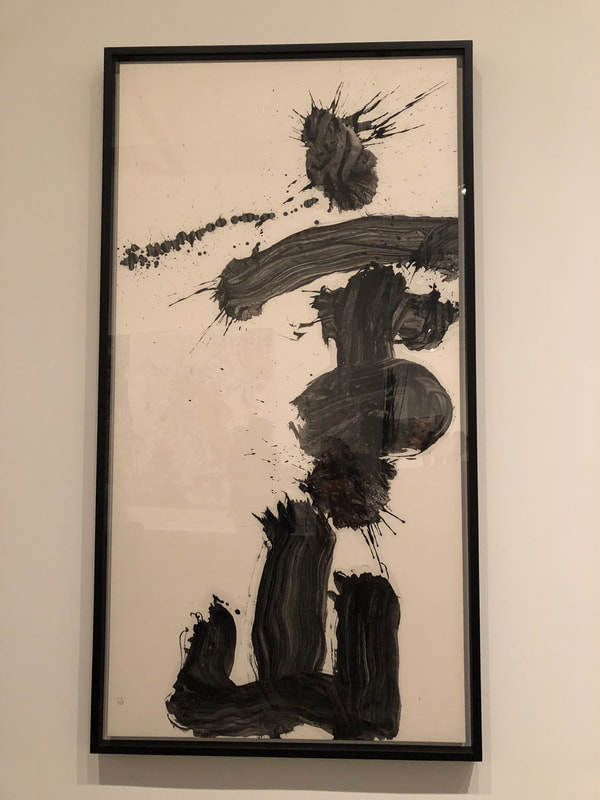

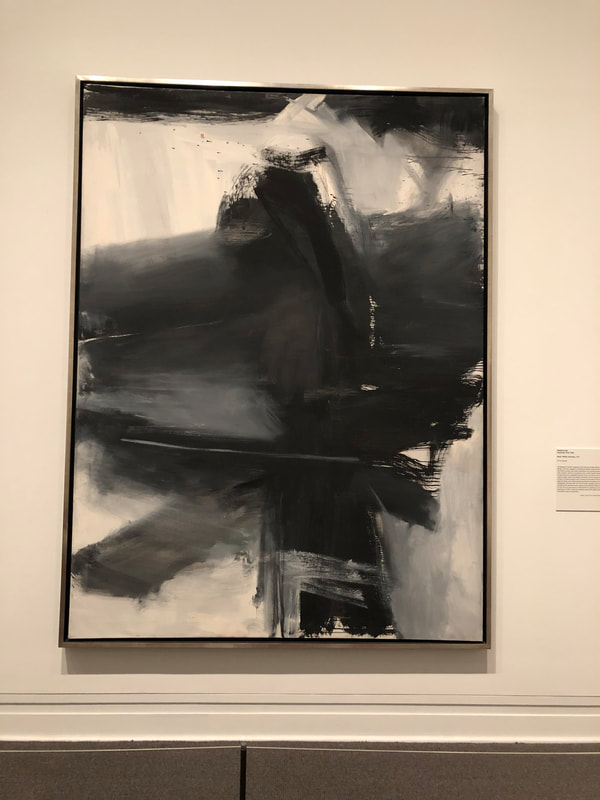

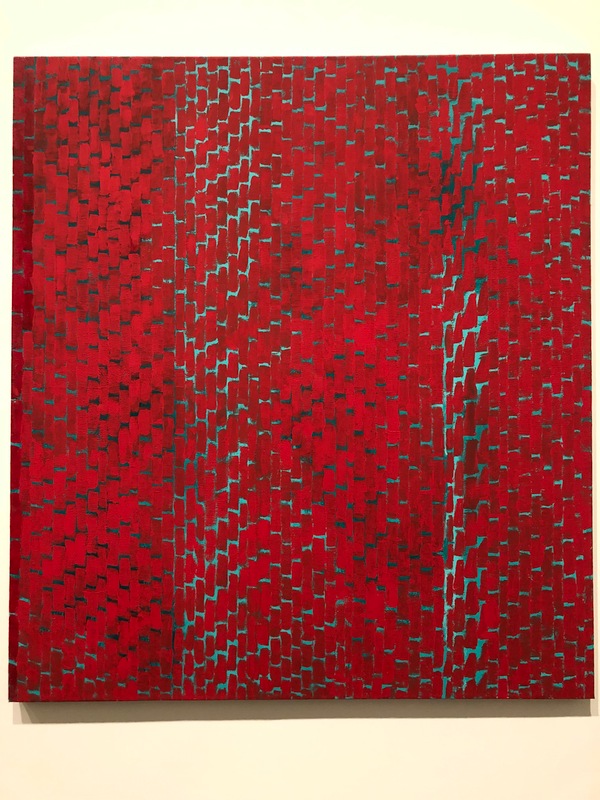

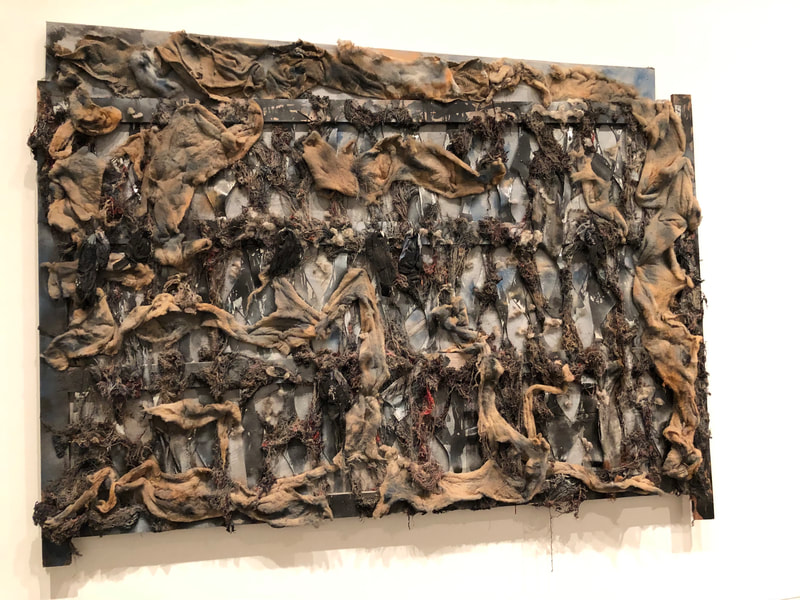

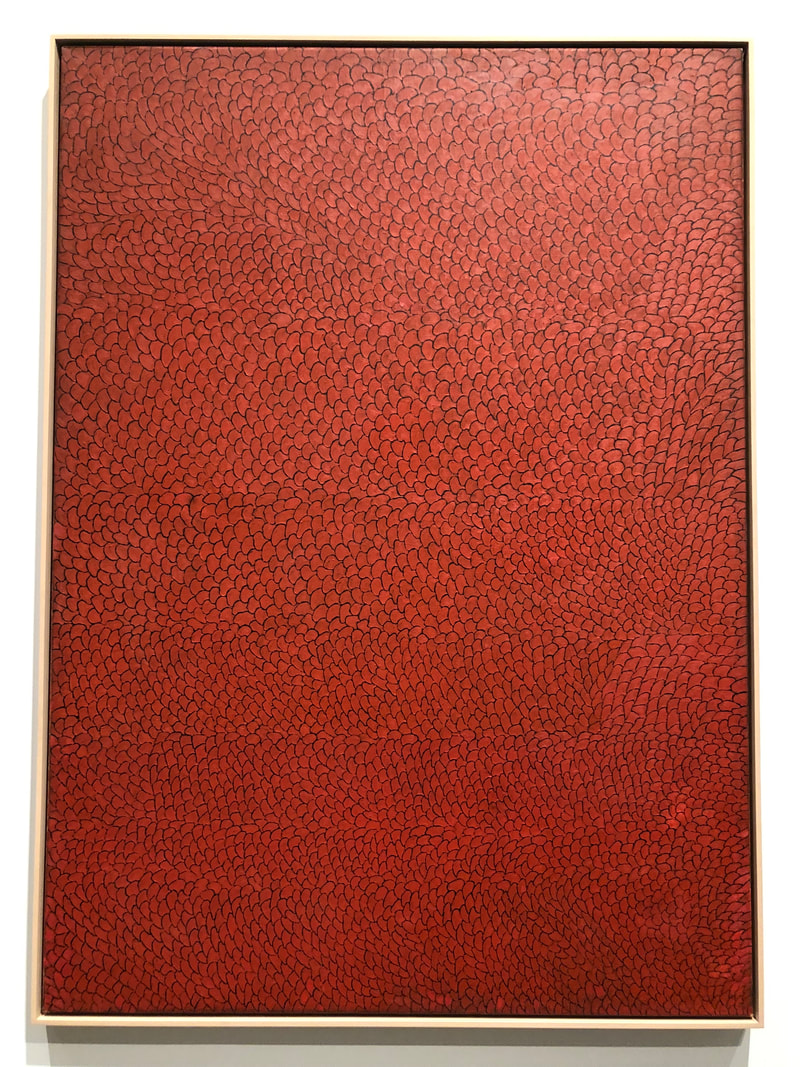

The title of Zora Neale Hurston’s most famous book comes from the sentence: “They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” This is an extraordinary sentence in a book full of extraordinary sentences. I read the book weeks after walking, for the first time, through the Epic Abstraction exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In that first encounter with Epic Abstraction, I was astonishingly moved. I don’t cry in public, usually, so I didn’t cry, but I’m sure my eyes looked bulbous and unusually filmed, for that was how they felt. My breathing was thrown off by some of the pieces; I felt a wonder, and a recognition. I felt emotional in a way that was both full and hollow. I wouldn’t have been able to say, with any truth, what it was about any of those paintings that made me feel this way. If you insisted, I’d have made up something which may have sounded eloquent, even profound, or may have stumbled out in some convoluted fashion. I had never before had this kind of first degree emotional response to art in a museum or gallery, and certainly never to abstract art. Of course, this had everything to do with me: who I was standing in those galleries, who I am today. But whatever the sources of this response, the effect was a completely new understanding of this art. Until this particular viewing of this particular exhibition, I’ve appreciated abstract art for its innovations in form, its deconstructions of the figurative, its intellectual conundrums, its challenge to knowledge and certainty, and its invitations to sense and know in new ways. But all of this was cognitive; if emotion arose at all it came from a secondary process of narrative meaning-making. This particular, January 2019, encounter with epic abstraction – mostly very, very large and very, very abstract pieces of art* -- was different in that these pieces simply in their size, form, color, and juxtaposition evoked a great helplessness and tearfulness. These words look silly and excessive, but my feelings at that time way exceeded these words. Which brings me back to Zora Neale Hurston’s sentence about eyes watching God. “They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” In my reading of this sentence, it’s not about faith in God, though the people she was writing about may well have been God-fearing. The sentence gets its power from bearing narrative witness to a moment of extraordinary humanness – only being able to live, only pressing to live, with all of its terror, helplessness, grandeur, consciousness, God. This was nothing so limited as “staring at the dark.” This was emotion, longing, life (and death) beyond words and cognition, but not reduced to animal instinct. Hurston has an animal figure – a dog – in the same hurricane-driven floods as her narrator, Janie, and the other people in “the muck.” The dog’s eyes were crazed, phenomenally “staring at the dark,” staring wildly at anything it could see, desperate to live through aggression. It turns out the dog was rabid. Even if Hurston hadn’t needed the madness for a narrative twist, I don’t think she would have said its eyes were watching God. I returned to the Epic Abstraction show a couple of weeks ago, eager to repeat and record my emotional experience of the first time. In the beginning, I thought too much. Feel, I told myself. That didn’t work. Then I just let myself write in response to pieces, and feeling returned, filtered through words, thinner, a trace, but there. Though I was not in a hurricane during that first visit to Epic Abstraction, and I was not – in a very real, palpable way – on the verge of dying, in retrospect I appropriated Hurston’s metaphor to understand my experience that first time. That first time, my eyes peeped through the art at God. That art, that day, expressed humanness beyond words and cognition, the fullness of human desire to live, experienced and expressed with the sensate and cognitive sensibilities of our complex bodies. We are not machines. One day an artificially intelligent entity may mimic, with great sophistication and nimbleness, every human function, but if it is cut off from corporeal humanness, it will only be able to formulate helplessness; it will not feel the helplessness of “eyes watching God.” What does all of this have to do with moral authority? For a long time I have been struck by the moral clarity and power of the writings – including fiction, non-fiction, and speeches – of people who’ve survived sharp and sustained exploitation by other groups of people.** More recently, I’ve had opportunities to work with people who’ve lived through histories and direct experience of sharp and sustained pain. I’ve had such opportunities before and I’ve risen to them well – thoughtfully, kindly, in facilitator-speak holding space for them to be themselves through the hard transitions of survival and being that they were living. But I was different in my recent, deep and lengthy, opportunity. I had my own experience of sharp and sustained pain. It was urgent enough that I couldn’t simply dismiss it as small relative to the pain of others, to the histories of grinding indignity and uncertainty that many others live with. Rationally I know my situation is not bad; of course I’m not teetering on the edge of physical or emotional survival. But, emotionally, I’ve had to contend with very real helplessness, and, in the work I had to do with colleagues in San Diego, I was inexorably pulled to feel it, express it, and connect it to the helplessness of others. In this work, my understanding of moral authority deepened. A few days ago, I grandiloquently told a group that I am currently deeply interested in how desire and emotion – especially love, fear, and shame – are foundational elements of moral authority. What is moral authority? one of them asked. Here is my answer, today: moral authority is the agency with which you relate to others, through words, actions, metaphors, images. It is essentially social, both contained by and spilling out of convention. In Buberian terms, it is the action of “I” in relation to “you.” In Biblical terms, in part via Jean-Paul Lederach, it is seeing the face of God, or not, in others. It is the living of desire and helplessness, mediated by socio-economic and political structures, shaped by linguistic possibilities and the grace or awkwardness of particular bodies at particular times, and expressed, consciously and unconsciously, in every act of living. Mostly, moral authority is expressed and heard as dogma or debatable logic – sometimes self-focused and self-serving, sometimes prosaic and parochial, sometimes ineffably greater-than and universal. In my view, moral authority gains an enormous power and tenderness when it draws on the lived tension between desire and helplessness, mediated by emotions that may be described as love, fear, shame, joy, anger, pain, and awe. Everyone experiences that spectrum of emotions. In my experience, those who are more aware of that spectrum in themselves have more clarity and kindness of purpose, whether within and in relation to the smallest units of dyads or families or to the largest of collectives and, even, to humanity and life in general. The Epic Abstraction exhibition surprised me by evoking my own helplessness at losing, and letting go of, my partner of twenty-eight years. Zora Neale Hurston gave me a metaphor for that helplessness. I’m still figuring out how that helplessness, and its attendant emotions, are shaping and will shape my actions in relation to others. Certainly, it’s already made me much more intensely aware of love in my life, love that I give and love that I get. It mostly makes me a kinder – some would say “softer”, lol – thinker (though a recent exchange makes me think that I am softer in some ways but clearer and firmer in others). It’s influencing questions and dilemmas in my fiction. I don’t yet know how the effects will show up in my political activity. We’ll see. A new Presidential election is coming up. The last election made me angry and hurt. It didn’t quite reduce me to helplessness, but I do feel fear and uncertainty and those, along with the thread of helplessness in my personal life, are shaping, will shape, the moral authority that drives my purposes and actions. * Notes on the structure and pieces, along with some photographs, are appended below. ** Parenthetically, I’ve also been struck by how slowly and in very limited ways such writings have been acknowledged, read, engaged, and drawn on by dominant groups. Raw notes on, and pictures of, the exhibition, first from my second visit, and then some memories from my first visit Coming up to the Epic Abstraction show from the southern end, I pass Kiki Smith’s Lilith, to me fearful and vigilant, sort of at the other end of desire and moral authority from Janie in Their Eyes Were Watching God. If you think of this spectrum as circular rather than a straight line with infinitely divergent ends, this end is the same as the beginning. To my eyes, Lilith looks like a precursor to Mystique in X-Men. A group of Euro-American people – two women and one man – just stopped to look at Lilith. Two of them are brightly, innocently, fascinated, especially by her eyes. The third, a woman, walks away saying, “It’s too scary, I don’t like it.” The first piece of art on my right as I entered the Epic Abstraction exhibition is New York #2 by Hedda Sterne. It’s equally divided between light and dark. Her signature is on the left, in the middle of the vertical plane. My eye is drawn to the dark, the tunnel, the sewer. My mind is working too hard to see and interpret form to allow attention to feeling. Next comes Cy Twombly’s Dutch Interior, which gives me the pleasure and permission of utter foolishness, at scale. “I don’t know what to do.” The artist is present in the action. Time passing. The space covered, not covered, done. Jackson Pollock’s November 28, 1950. Museum clickbait. Overseen. Too confident. Is it his ego I resist? Is it my ego that resists? Moving on. Clyfford Still’s 1950-E. I’m comforted by the burgundy at the bottom. It feels right, balanced, the burgundy, left bottom; blue, right top-ish. Much more black than white, as much grey as black. A comforting painting. The last painting in this first space I entered from the Lilith stair is Conflict (1956-57) by Alfonso Ossorio. My eyes were drawn to this piece when I entered – it’s opposite Sterne’s New York– but I left it until last. It makes me feel alive: the red heart, the three-dimensional explosiveness, with textured paint of varying thickness. The color palate is human – blood, shit, skin, bone. In the middle, more or less, of this first space is Barbara Hepworth’s Single Form (Eikon) (1937-38). I ignored this sculpture the first time I walked through this show, sort of dismissed it. What was that about? It’s too classic, too phallic, too heavy, too large, too squarely confident, too masculine, derivative. The sculpture feels like my past, unlike Lilith and Booker’s Raw Attraction (coming up). But when I force myself to look at it more closely, I’m moved by the wings of the pillar as it expands up a little, by the trickles or ripples down the sides of the square block pedestal, including on the broken corner of the block. Most of the paintings in the Pollock and Rothko rooms slip past me in their familiarity. Kazuo Shiraga’s red and black untitled (1958) is in the Pollock room, right near the entrance to the exhibition from that end. I like it a lot. In the Rothko room, his No. 21 (1949) stands out. It feels uncertain, fading. I expected it to be a significantly early or late painting, but it is dated right in the middle of his painting life. The other piece of art in the Rothko room that stands out to me is Isamu Noguchi’s Kouros, a very large sculpture made of pink Georgian marble. Kouros is a youth, male. This sculpture is not a young man. Or maybe it is. It’s smooth, confident, supple, large, and fragile. The room that really drew my imagination on this visit is the one dominated by Chakaia Booker’s poky, horny, piping, leaking vagina (Raw Attraction) in the corner of the room, flanked on the right by another very large painting (untitled, 1960) by Clyfford Still, this time red is the dominant color, not as comforting as 1950-E (which, by the way, looks ominous from this seat in front of untitled 1960; the black and grey merge from this angle). Still leaves a few light striations, almost drips in the black and in the red. One of these is in the black, right in the center, in the bottom half of the painting. It looks forgotten, a flaw he deliberately forgot. On the left flank of Raw Attraction is Mark Bradford’s Duck Walk (2016). Wow, what a fantastic painting, mixed media. It makes me come alive. The left panel is mostly white with yellow-mustard in the middle, the right panel is black in the middle, yellow swirling out. I see anime faces in the left panel. I like that there is no red in the painting. The color palette is spare. White, black, yellow, and some beige. [Comment added while typing these notes in: His name had sounded familiar, but I only now remembered why. He recently added What Hath God Wrought to the Stuart Collection of remarkable outdoor art at UCSD.] Completing this space are two of my favorite paintings in this show, in large part because they are side by side: Inoue Yūichi’s Kanzan (Cold Mountain, 1966) with stylized renditions of the characters for cold and for mountain and Franz Kline’s Black, White, and Gray, 1959. Almost ending the making of this space is Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 70, 1961. The emotional impact of these artworks in this made space is as much due to the curation, the placement of a work in the space and relative to other pieces, as to each separate artwork itself. And then there is the fabulous, hermetic, almost 21st century video game image – Judit Reigl’s Guano (Menhir), 1959-64, a layered painting: like history, like death, like a reproduction of fallowness – that transitions me into the extraordinary female-human-20th century space dominated by Louise Nevelson’s Mrs. N.’s Palace, 1964-77. -----End of direct notes --- The second trip, of necessity, because of a phone call I was committed to making, ended there. I don’t have notes from the first trip, all I have are memories that are now thoughts in the present. I remember loving the unapologetic size, steadfast standing in place, and geometrical complexity in monochrome grey of Mrs. N.’s Palace, surrounded by sharp-edged images created by men, and also rounded, even sentimental, images created by women. Reds drew me on that first trip as well. I gazed at Alma Thomas’s Red Roses Sonata (1972) and Elizabeth Murray’s Terrifying Terrain (1989-90), and felt the threat and harmony of each. I shied away from, then stared at, Thornton Dial’s Shadows of the Field (2008); now it looks ominously like a faded, tattered flag, millennia before a fossil, though this soft tissue of history and affect is lived in consciousness or disappears. The color palette of Frank Bowling’s Night Journey (1969-70), the yellow falling through the horizontal center, held me, though I found the continents distracting in how they historicized color and shape. Finally, the exhibition ended (or began, if you came in that way) with Yayoi Kusama’s No. B. 62 (1962): mostly evenly red shells or scales, in retrospect a carapace, perhaps the curved surface of that odd creature, a pangolin, laid out in two dimensions. Postscript: I was hesitant to post this piece, even after proofreading it and uploading the photos. This morning, a beautiful, sunny spring day in NYC, I had to make explicit the life and joy I also see in and through the helplessness and moral authority. If you live, you fall in love with life again (thank you, Andrea, for your Facebook cover picture), even if only in small ways, and in that falling in love, you claim life for yourself, and often claim it for others as well. Janie (and Zora Neale Hurston) did that, the Epic Abstraction artists did that. Reading Hurston, and walking through the exhibition, and looking at the sunlight today, I am doing that.

Anna Seghers’ Transit is astoundingly contemporary, though completed in 1942.* In the most practical, palpable ways, the book describes the pillar-to-post, paper-and-more-paper, and rules-petty-power/lessness-and-helplessness of trying to cross a national border when you are wretched. The novel was written in the middle of the 20th century, the nation-state-century, when the science of borders became so fine that it could define in OR out, pure OR impure, and even what morally belonged as opposed to what must be kept out, just by whether you filled in the correct forms correctly, which allowed the gatekeepers to see quickly the lines that ran on one side and on the other side of you. A primary line running right through you did not, does not, bode well.

I entered a mild form of that kind of transit world in the 1980s and early 1990s, as I went to and from the United States as an Indian citizen with a U.S. student visa. Today, as a U.S. citizen of some means, I rarely have to enter that world. In 2018, we still seem to be in a long nation-state-century, though perhaps we’re in a globalized-hyper-transit century. We won’t really know until the evolving science of borders catches up with contemporary phenomena, forms, and technologies. So that’s it for the most obvious point to be made. Transit, the novel, was wholly suited to being made a contemporary film, which it has been. But Transit is not just a novel that has contemporary resonance. It is a story that is both fascinatingly flat and intensely dynamic. It is as if Seghers cut a slice of a whorled, recurrent world – that she calls an “ancient, yet ever new … … present” – and conjures for us all the details – people, forms, places, ships, days, victuals – as they move, connect, break down, reconnect, slip off, and are replaced. The story is narrated by a young man, in my view with the voice of a mature woman (plausibly a mature man, but implausibly a young man). In that period, a woman could not easily have wandered, gazed, and desired, so the narrator is a young man who is a curiously passive and blank character. His main foil, a young woman, another blank character, is hyper-active and always running after. Third in the key triangle of the novel is the explicitly blank character – for all practical purposes a fantasy – of a dead man, a writer, whom the narrator pretends to be and whom the young woman seeks. The story of these three blank characters becomes the web that holds the world of transit in Marseilles at the beginning of World War II. Strung on this web – moving along, sometimes jumping off or jumping back on – are small characters, socially and otherwise varied, who are perfectly alive. Encircling the web are small, and larger, and overlapping, environments – cafés, waterfronts, stairs, rooms with a wall on this side and a wall on that side, a view of the sea beyond “where the road took a turn and the wind was the strongest” – which add up to what Marseilles was at that time, but also, as peopled by the various small characters, to the state of transit as the roiling object of the story. Anna Seghers draws us in with the seductive narrative threads of quest, adventure, impossible love; in a curious inversion of the Orpheus-Eurydice myth, Marie runs after death and finally meets it. At the end, these narrative threads remain thin – almost transparent, almost air – but sustain a busy world of “present,” with all its waiting, living, and small moments of kindness and loving amidst known meanness, desperation, and death. The basic triangle, the detailed representation of place, and the reliance on small, recurrent characters are not unusual.** What is striking about Seghers’ novel is the deftness with which she uses a somnambulistic, Heinrich Böll’s word, narrator to tell a compelling and dynamic story about a slice of time. * It was first published in English and Spanish translations in 1944 when Seghers was in Mexico, and appeared in German in 1948 when Seghers was settled back in East Germany. Seghers’ choice to live in East Germany was controversial. The permanent return of the authorial voice of this novel to East Germany does intrigue me, but maybe only because I have some deceptive clarity of hindsight and distance. ** Reliance in long fiction on a wide variety of small, recurrent characters seems to belong more to places and times where lives are crowded and not as socially segregated as they seem to be for the dominant literary writing classes of the United States. WARNING: If you have not read the book, there are spoilers in this review.

Like many cosmopolitan, post-colonial South Asians, Hari Kunzru writes extraordinarily well. He knows and loves words in the English language, not just the functional language of the British Islands, but the de-territorialized language of twentieth century globalism, kneaded by diaspora intelligentsia, whimsically dipping into the vernaculars and dialects of English-speaking localities, and – in Kunzru’s case – ironically, but also desperately-lovingly, seeking to use English, a language of modern power, as a moral language that mourns, assesses, and stays alive. In White Tears, he writes beautifully and he has a fabulous, intelligent, moving, and unusual concept. As an aside, but this is important, I came to the United States in 1980, a post-colonial Indian, fresh off the boat, not knowing the blues at all.* I’d heard jazz and rock, and, yes, I may have listened to Billie Holiday, but simply as jazz. I did not know the blues. In the early eighties, three young white people from North Carolina introduced me to the blues. A few years later, more white people introduced me to more blues. No African-American has introduced me to the blues, though one here, or one there, may have listened to a song with me. White Tears is about the blues. It is also about incarceration, racism, American government, guilt, and blaxploitation. I read it after J. Saunders Redding’s No Day of Triumph, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, also some Flannery O’Connor, but before Marilynne Robinson. This context is important because it reflects one thread of twenty-first century grappling with “race” in the United States: immigrants, especially non-white immigrants, consciously – intellectually and morally – adopting and owning the race history, and the racial present, of their new country, trying to find to find an American identity between, or beyond, the two easiest choices: “to assimilate into White culture or to appropriate Black culture.” ** The main characters of White Tears are two young white men and a vengeful black ghost. The two white men love music, particularly the blues, particularly the richer white man. The poorer man is adept with technology, the richer is a collector, and neither is good at navigating the moral delusions of human societies. Kunzru sets up a gorgeous plot device which begins with Seth’s hearing a song fragment while randomly recording street and other public sounds in New York City. It leads to a theft of intellectual property, of cultural property. We don’t know it, but the past is vengefully inserting itself into the present. We get a hint of mixed realities but the language of reality keeps us grounded in the present. The rich boy, Carter, gets beaten up and disappears into a coma, but we are not sure if all of that is real or a delusion. The remaining boy (Seth) knows that the attack on Carter has something to do with the theft of the song, but he believes that the threat will be dispelled if he can explain and prove the innocence of the prank. Meanwhile, he has geeky hots for Carter’s rich sister (Leonie), is conned by a journalist masquerading as a friend, and draws Leonie into the retracing of a tragically exploitative trip, during which she is pruriently murdered and he falls into his first full hallucination of white face-black face. From that point, the narrative spirals towards to the climactic integration of evil-innocence-cluelessness-privilege-death and subordination-suffering-incarceration-ghostsofChristmaspast. The problem with White Tears is it is not a tragedy. The bad people are unambiguously bad. Revenge is simple. The innocent are clueless, and cluelessness is not innocence. Kunzru’s story is very powerful, relating a national, indeed global, history of extreme exploitation, of capitalist and racist privilege, of systematic cruelty. This is a story of deep red and black strokes. The flaw in White Tears is that he tells it with deep red and black strokes, but he – diaspora brown, and post-colonial like me – does not have adequate color capacity for it. Coates tells it black and red, unrestrained, and sometimes tenderly, from his heart; he himself grows in the telling. Redding’s 1942 travel memoir is written with a post-War, pre-Civil Rights optimism. His telling is fluent and dispassionate, skillfully weaving literary English and the vernaculars of the southern localities he visited. With scholarly calm, Redding chronicles harsh and casual racism, and the human frailty of Southern Negroes (as they were called in the forties), whether beaten down by poverty and racism or, if well-off, struggling to reconcile racism and economic privilege. Americanah’s narrative goes from the ordinary color consciousness in a non-white, post-colonial, independent state – in this case Nigeria – to consciousness of racism in the United States, with a side journey into racism in England, and back to a twenty-first century globalized consciousness of race and color. Like Kunzru, Adichie writes with all of the skill and confidence of the educated post-colonial cosmopolitan. She claims all of the English language, and writing phenomenally, so to speak, claims all of the colors her novel can bear. She cheerfully presents us with types, and then just as exuberantly adds their ingrown hairs and pretensions. In the end, Coates, Redding, and Adichie write about flawed people loving, exploiting, or being clueless about flawed people. Held against them, albeit serendipitously, Kunzru writes about bad, or consciously false, people exploiting weak people. In White Tears, Hari Kunzru writes a superbly ambitious story. He manipulates structure, language, and plot both intriguingly and smoothly, and his characters are often perceptively drawn, although sometimes with more self-conscious irony than needed. However, in this brave effort to write about race in the United States without (simple) assimilation or (strident) appropriation, Kunzru loses his voice, and as a result no character is full, not as black, not as white, not as female, and not even as male (or other gender). The characters who are closest to being full are the two lonely older (white) men, JumpJim and Chester Bly who move through their ghostly parts in ways that are both lumpy and alive. They are not stock characters dressed up; they have shadows that allow me imagine into them. JumpJim shuffles and obfuscates in palpable ways while Chester Bly travels through the south like a lovingly-rapacious white doppelgänger of J. Saunders Redding. To the degree this review sounds critical, it is not about throwing shade on Kunzru for misappropriation nor is it calling on Kunzru to add a “brown” voice if writing about race in the United States. Rather it is a rumination on the difficulty of trying to write about race in the United States, where every word takes a stand and every word can be hurtful. One path to safety is to write what, at its fullest, is an uncontrolled narrative in a highly controlled way, where the writer is apart and in control always. The rub is that ‘to be in control always’ can only be achieved with a limited range of representations. This means that the writer risks being more on the mechanical end and less on the “live” – internally conscious, escaping, haphazard – end of narrative representation. As a South Asian diaspora voice, Kunzru writes very carefully about race in the United States. He is not afraid to personify the badness of racist capitalism and the will to vengeance of the historically exploited. But, in a curiously ironic way, while he makes the blues the heart of the story, he loses the pathos of the blues which is a human pathos. The whiteface-blackface-whiteface torment in Seth’s story comes the closest to pathos, but Seth loses palpability as his delusions are cleverly articulated. In the end, his delusions and hallucinations come across more as elaborately didactic representations of the delusions and hallucinations of racist capitalism than as human pathos that wends through will to/subordination to power, desire, suffering, love, weakness, and death, though not necessarily in that order. * For more on my slow, always incomplete, learning about race in the United States, see my blog post The Color of People. ** Mallika Roy, Hardly Un-American In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty tries to find an economic driver of structural inequality that might be amenable to policy control; he finds that capital income contributes strikingly to increasing inequality and that, potentially though not easily, its effects can be reduced by tax policy. Most discussions of his book focus on his academic work of data gathering, analysis, and theory-building.

A second intention gets less attention. This is the intention to engage directly in public discourse: not simply informing public discourse, nor simply a written form of public speaking, but seeing himself and his work as direct participants in a marketplace that includes ordinary, not-scholarly, not-official people and, presumably, their language and ideas. “Social scientists, like all intellectuals and all citizens, ought to participate in public debate…. It is illusory, I believe, to think that the scholar and the citizen live in separate moral universes, the former concerned with means and the latter with ends.” For me, the charm and importance of his work, well beyond the competence of his (and his team’s) data-gathering, analysis, and theory-building, derives from this engagement, unabashedly personal, with a systemic moral universe that includes the scholar and the citizen. I started reading Piketty’s Capital around the same time that I read the transcript of Marilynne Robinson’s conversation with Barack Obama, and immediately promised myself that I would write this post, because Robinson and Obama’s conversation has the same quality of ranging outside the lines of conventional or official categories. In a back-and-forth that comfortably meanders from careful phrases to sentences that try to capture a truth so intensely they immediately reveal their own limits, then on to rambling words strung together thinking-out-loud, Robinson and Obama discuss the importance and meaning of Christianity in Robinson’s life and writing, the language and role of Christianity in contemporary politics, the gap between ordinary decency and mean-spirited politics, and race in the US, among other things. It’s not that such discussions are unusual or that the content is extraordinary; what is remarkable is the ease with which Robinson and Obama make the ordinary* commute with intellectual, author, President, in a public conversation. So, why am I writing this post? Because I was invigorated by Piketty’s, Robinson’s and Obama’s smudging beyond the boundaries of expertise and the lines of disciplinary language. I loved their engagement beyond the professionalization of their, and our, lives. In his book and in their conversation, these three people – Piketty, Robinson, and Obama – bring intellect into direct contact with ordinary life, in the public sphere. I hear their words bringing to the fore, in a wonderful way, an obvious but usually subdued understanding: that all people – social and political beings, whether “intellectual” or not – have equal stake in the moral universe that human society necessarily is. * here a noun Marilynne Robinson and Barack Obama chat on Sept 14, 2014 Part II of Robinson and Obama Chat |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed