|

Composition: the artist as impostor

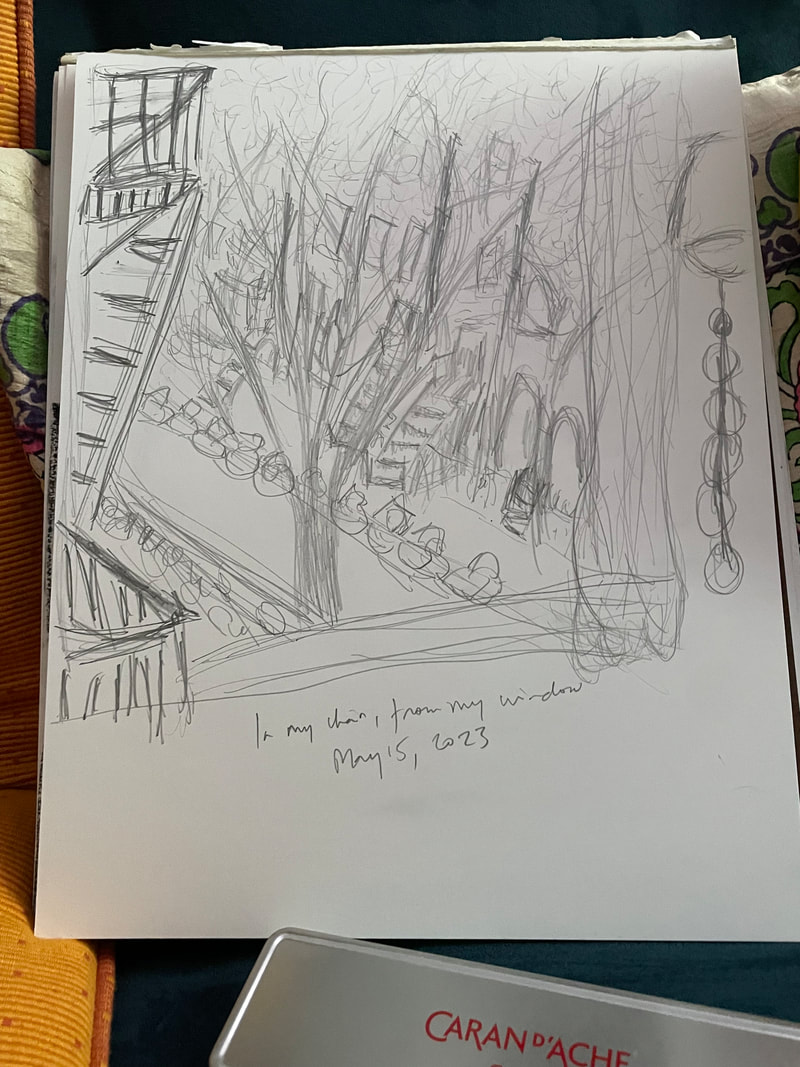

Composition: writing like a visual artist Composition Routine Joy When I start a new piece, I throw myself into writing, a sensual, wordy mix of hand movements — fingers tapping, or moving pen — and the heady intoxication of words, like a visual artist drawing and cutting lines through space, always falling short of the depth of each perspective, each frame, and the grades of light and shadow. I don’t know what is going to happen. I clutch an idea, something between a prop and destination. I propel myself beyond foolishness and prophecy. I, unfailingly human and impostor, am representing life, the world, something like that. The words themselves have histories. Composition, put together. Impostor, put upon. Grade, measure, step. If I stick with this, I’ll lose myself, probably you as well. Where is the idea? Seeded in two layers of ordinary life: routine joy, and the tree outside my window, which means the window, the tree, the street bounded by humped cars and brownstones, shadowed stairs and arches, and my eyes catching the light, filling the continuity of that farthest wall through the opacity of branches. My sketch captures only lines and the barest wispy movement of leaves. I started the sketch because I wanted to do some fresh writing again, after months of revision and reading. Not my fourth work yet, there’s more revision to do. Just a short piece, a blog post. On what? Nothing in particular pushed to be thought, to be written. My thoughts are bucketed, moving forward in orderly ways. Those gentle buckets shepherd my unruly feelings as well, expand to give them space, and hold them. After many years of change, my life has fallen back into a routine in which I am loved and loving, some people honor words I utter in writing or in direct relationship, and my coffee is good. There is a routine joy in my life. I laugh more easily. In the gaps between working and loving, listening and caring, I step out with an easy frivolity. It’s a happy feeling. But wait, how much can I write about that? It doesn’t hold the meaning of life — whatever that is — and I know its evanescence, I know some — many! — of the shadows below it, it being that routine joy. Presupposing the limitations of that routine joy, I couldn’t start that new writing and so, itching and driven to do something, I sketched the tree in my window, which, as I have already said, is not just the tree. I was sketching again after an even longer break than writing, about a year and a half. As with the blankness that met my fresh writing intention, there was no particular shape or emotion that revealed the subject-object of the sketch. But I love looking out at my street from that window, and that tree is a mirror; also beautiful, with some dead branches, and changes with the seasons. So the tree, of course! I anchored the sketch with the fire-escape and now one might say the sketch is of the fire-escape, anchoring as it does everything that’s also in that gaze. This was a very frustrating sketch. I have no illusions about myself as a visual artist — I’m just a scribbler — but I couldn’t capture the range of perspectives that my eye does, that I can sense! Does the photograph capture more than the sketch? It has more shadows. Or does the sketch, with the shiftiness of my eyes and the frustration of my hand, capture more than the photograph? As representations they are both my impositions, my sorry expressions of what I sense and feel and think. But, sorry or not, they are also expressions of my life reaching out and touching life on my street. Spring is so beautiful. This same street has lived garbage, winter, storms, covid, solitude (both still and staggering), collectors of recyclables — the hardest working!! — and now, with me, routine joy, from me, but not just me, not just joy, but, yes, also joy. As I cannot raise despair to flat, so I will not reduce joy to flat. I am alive with all of it.

0 Comments

Madre and desmadre

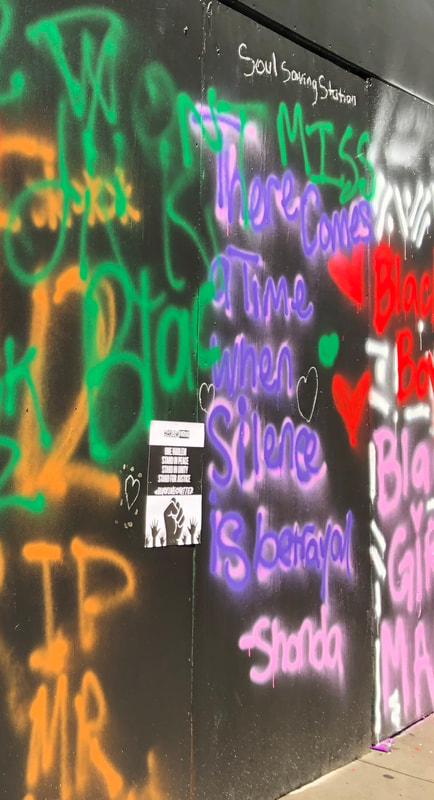

I very recently became aware of a Spanish word desmadre, first spoken more generally in my presence and then directly to me by a group of magnificent women in the centre of San Diego. I was told desmadre means ruckus. The way I heard them use the word, it sounded like John Lewis’s “good trouble.” I thought it was two words. Of mothers? No, no, I was told, one word, meaning ruckus. The word intrigued me. Does it have something to do with madre? Well, of course it has something to do with madre, I found. It comes from a root of separation from the mother. Disintegration. Chaos. And now good trouble. In my three works of fiction, all the main characters are women: two wandering mothers, one grandmother, many daughters. My first and third work are about separation from the mother, in one case chosen by the mother, in the other not chosen by the mother. I wanted to close these books, close the stories, go from heimlich to unheimlich to heimlich -- the formula for a good novel I was glibly instructed by a literary agent with unliterary tastes — but the characters are broken are broken, whole only in the luminescence of the world in which they live, loved and loving. Earlier this year I presented the artwork edition of my first novel, Night Heron, in Berlin. My daughter introduced me, moderated the presentation and asked me how I came to write this novel about a visual artist who leaves her son for no very good reason, neither heroic ambition nor poor traumatic past. For the first time in all my stumbling, convoluted speaking about this novel, I spoke about the motivating ambition for this story. It was simple and too ambitiously silly to be spoken of before this, but there in Berlin, speaking to my daughter and a group of mostly artists and writers, I said I wanted to create a female Stephen Dedalus, as in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which I had loved as a young woman. I wanted a woman to step out as vividly: the language, yes, but also that stepping out. I found no Dedalus. There was no easy Dedalus, no female derivative who felt remotely real or interesting. My own life at the time — a mother of young children — pushed me to the not-Dedalus figure of a mother of a young son, and then she leaves her son, which is experienced as desmadre by all readers, disturbingly and uncomfortably so for most, satisfyingly provocative in a melancholy way for some. Art and writing has often propelled or reflected desmadre, traditionally in most parts of the world in the voices and through the agonies of men, often men with, or aligned with, more power (though they could and often did write about men of less power and even women). In the last couple of centuries that has changed. This change has become more rapid in the last sixty years or so as women and traditionally less powerful men — less powerful at least in the context of our long modern era of military gunpowder, industrialization, colonization, and rampant capitalism — have explored what it means to articulate main characters from their own experience of work and living in crowded interior and exterior worlds. Which brings me to an early stimulus for this blog post. A few days ago, biographyof.red, an extraordinarily delightful Instagram account that evidently springs from Anne Carson’s work and posts mostly poetry, posted an excerpt from Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. The excerpt, in turn, quotes Henri Bachelin on the conjuring of myth - involving “tragic cataclysms” of the past, and ends of times — around winter hearths. Evidently this conjuring comes from men, most definitely not old women who tell “fairytales.” Bachelard’s and Bachelin’s lovely words inscribe the space in which old masculinist myths can loom. Their words projected to me a willfully blind desire for understanding that penetrates “the end,” that grandly foresees its own tragic failure. I refused this space and asked myself, what larger space do I make, what poetics if life is the hurling of oneself — whether slowly, grandly, or awkwardly — against the hard transparency of end? What poetics, what space for people living splintered lives — loving, working, laughing, living — and expiring despite themselves, where narratives of yawning pasts and distant ends are often unheeded? Yes, yes, I know, Shakespeare, Dickens, the novel. And, yes, how does this relate to madre and desmadre, apart from the obvious gender stuff. Well, yes, the obvious gender stuff is key. Madre, a trope for connection, with all its connotation of home, gathering, shared food, shared corporeality, cooking, fire, transformation, sometimes even hearth. Complaints, shush, small tales, snoring, reaching into “forces and signs” by women and men. Desmadre, inside and outside. Inside and outside bodies, inside and outside that gathering at the hearth, inside and outside the home, heimlich always roughly pixilated, parts spinning into unheimlich, unheimlich pressed into new forms of homeliness by personal and collective intimacies. From trope to subject, madre to desmadre, women and the historically less powerful are saying we will occupy this hearth, we will make the space under crossing highways a hearth, we will make it a space for life, for gathering, for drought-resistant plants, for art that exclaims “we are here!”, and here encompasses the beauty and pain of our pasts, the struggles and dancing of our present, and our shared future of children, life, and death, all of that! I didn’t know how this blog post would spin out. It is still spinning within, tilting into aliveness, spilling into uncertainty. Madre and desmadre are mythical figures of worlds that have long been binary-gendered. As binary gender dissolves into two figures in a much larger flow, or if gestation becomes incubation in genderless machinery and separation becomes connection to a human, will madre — traditionally female, one of a binary, bloody and corporeal — change? I don’t know. The best I can do for now is to observe that the binary was always only a device, a tool for organizing rhetoric and meaning. The non-binary has always been available, residing in both vast madre and desmadre. Reflecting on the mothers in my fiction and the space-making event alluded to above, madre also seems to connote separation and desmadre also connotes connection, gathering. Age may have something to do with it, but I’m not sure. I was safe from March 2020, even before that, and I’m safe enough now. I was healthy enough to start with, and had enough money. Two grocery stores near me were open, a friend sent me a mask when I needed one, my daughter sent me more, I bought a few, I had lots of Zicam, ibuprofen, and Vitamin C, and I live close to the river, which means I can walk by the water. I had my phone, and FaceTime and Zoom. For some months, the only real people I saw were on the streets, in Duane Reade, and in my two grocery stores. People died, many people died in New York City; I didn’t know any of them. In May I saw a morgue truck a twenty-five minute walk from my home. Then one of the grocery stores shut down, the one I favored; it had been struggling already. I already had a practice of drawing pleasure from small evidence of life or shape: a sparrow; the magic of a male cardinal, his insistent courtship; the loud cacophony of birds in the morning; the small bumps on branches outside my window that grew and burst into fragile green then darkened to heaviness; the early yellow of some hasty fellows, some as early as June; the fall; the winter again. But now I saw and felt more of these, and more than these. I gazed at the shadow of the locked gate on my fire-escape window. I watched the light of the late gibbous moon swell until it was full through the gingko in the backyard. The plants silhouetted against late light in neighbors’ windows became my friends in the night. A trumpeter played and played and played until two or later in the night; then he was gone and the lights stayed off in those windows. I watched mourning doves squat the abandoned blue jays’ nest outside my window, lay eggs, share brooding duty, then one dove disappeared, the other tried, gave up, and the eggs dried to shells that caught the wind and blew away; in grief and greed I prised the nest away and tossed it to use the fire escape for my solitary Covid wine. One May evening, that same May when I saw the morgue truck, when I went back in to replenish my glass of wine, I found G from downstairs with two policemen at my metal-sheeted door. Someone had heard a shot. No, it wasn’t in my apartment, not even in my building; I hadn’t heard the shot, I never heard any more about it. Through all of this my beloved solitude fell in upon itself, and I wept my losses of the past and the desperation and afflictions – the rising illness, deaths, helplessness in my city – of the present. Then the woman with the unleashed dog called the police on the birder who protested, and then George Floyd was murdered. Black Lives Matter, the weight of history, the pain, but now we had a cause, a bigger-we though not all-we.* And Trump amazed me everyday. This small man played the role of incoherence, instability, falseness, indeed the honesty of falseness, it just is he’d say, usually loudly, this is who I am, this is life. We had to get him out. It’s not that I dream of goodness, not that much anymore. The world is breaking and even we in the United States are sliding into horror. Oh, we already had horrors. Horrors – most horribly of our making, believing ourselves good, or we just said that – have accompanied us throughout. Some of us were rich enough, some white enough, though white by itself was not always enough, to choose not to see, not to hear, not to smell, not to feel. Through all of this I had joy as well: the river I mentioned, the spring, the summer; walking miles and miles to meet a friend, each weighed-down, delighted, to see the other, although we couldn’t touch. Later we picnicked in a city meadow, blankets six feet apart, with cocktails that were peddled by hurrying men, $10 for a mojito or a margarita in a small plastic bottle. What joy! Perhaps most dear, my daughter, graduating on Zoom, came to live in NYC with her partner. And then, in September, my children, my friends – Covid be damned – managed to make my sixtieth birthday one of my best ever. In the fall, I had Diwali dinner with some of these beloveds, and in that fraught and hopeful winter, Christmas dinner right as Covid knocked closer than ever before. An intrepid friend went to visit her parents in India. Time to visit my mother, I decided, and so I followed. We’d talked everyday, my mother – then 88, now 89 – and I. We’d been alone, more or less alone, ten thousand miles apart. I flew, double-masked with NYC caution, quarantined for a week then had a test, negative of course, so then why the intense relief? Paranoid Meenakshi with her old mother, paranoid old Meenakshi from NYC. I loved the light and warmth of Goa, the food. I learned again the joys and irritations of living with someone. I touched the passing of time in my life and the lives of loved ones there. Old friends, new friends. Cases started going up, sneaky small numbers with their sneaky high rates of increase. Most people there, and elsewhere, did not worry; I worried, but not a lot, not enough. And I did not write, I did not write, I did not write. I had not written in a while and that did not change. Instead, I sat heavily or jumped. Time was passing and with it my relevance it seemed. Two months in Goa, during which I got my mother vaccinated and old-enough me along with her, and “wonder of wonders, miracle of miracles” – yup, I sang that over and over in my Kolkata Catholic high school’s production of Fiddler on the Roof more than forty years ago – I heard that I-Park had a place for me in the second session of their reopening residency program. I-Park, the name, the residency, became a time beacon, a stable place in what felt largely like a life of uncertainty and irrelevance, though reasonably comfortable and safe. Meanwhile, cases were still going up, in India, in Goa, which was worrying but not alarming yet. All of it worrying enough, though, that stress built as I prepared to leave and helped prepare my mother to return to her north Indian home. Luxury would help I thought, so I blew a wad at upgrading which, on Qatar Airways, meant a little room of my own, cotton pajamas, and good wine. On that plane, a 14-hour flight, I wrote more than I had in months. I felt only relief, not even guilty at feeling no guilt. NYC was getting vaccinated! I returned hopeful. I’d crossed watersheds, crossed something, crossed over, I thought. I was ready to start anew, rebuild life with my loved ones, build community with new friends, new loved ones, get politically active again to build the world I want to live in, or at least to heave against horrors of the past, present, and future. And of course to write again. And now perhaps to find loving eyes for my writing, people who would keep reading my words, their bodies suffused with “aha, I know this, it was always there.” But my hope turned out to be only exhaustion – from what, you safe and upgraded woman?! Even my upbraiding of myself was exhausted. I didn’t write. I worked through practical tasks, continued to be warmed by those who love me and whom I love, put one dragging foot after the other in the sand of this new shore, was it even a new shore? India sprung into disaster, death, death, death, burning. And I started hearing from friends and relatives that a loved one, often more than one, had fallen ill. Some died. My mother stayed physically well but fearful and lonely. I stayed physically well in increasingly vaccinated, open, and green NYC, and I felt exhausted and lonely. I met and talked to friends and family. These conversations reminded me that I was well-loved and not alone, but it was as if the months of my Covid confinement – of the body certainly, but also of the fearful, uncertain mind – had led to a separation of the physical (or external?) me – “I’m ok, actually I’m well” – from some other me held in the same cells of that same body – “I’m exhausted, uncertain, alone, so what.” I didn’t write. Through all this there was joy as well. That river (the Hudson!). Spring again. Noisy adolescent birds. Sitting back with pleasure, though still outside, at a favorite restaurant. My older child came to visit for two weeks, what joy to have both my children with me! Friends continued to love me and be loved. I even met two more men I liked well enough to meet again. If you’ve seen or heard me in this time, I look well, I sound strong, I laugh quite a lot, and all of that is truly me as well. I-Park remained a beacon, straight ahead; not an Avalon or Shangri-La or paradise of any sort, just a place and time of calm in which I would be still and deep, and write. I rushed to finish as much as I could of my busy practical work. Person after person who heard about the residency wished me well. And so I came to I-Park, masked in an ordinary way, in an ordinary crowded train, and found a place that no one deserves, so I draped myself with this time and place as a gift, a module of life and living that is not willed, that is out of my control. In a way it’s like an upside down Covid. It’s beautiful here, with green, green, green, a pond, and site-specific ephemeral art on wooded paths. A path runs through Thanatapolis, city of death. Prediction, or prophesy, simply means the stating of what happens: it’s happened before and will happen again.

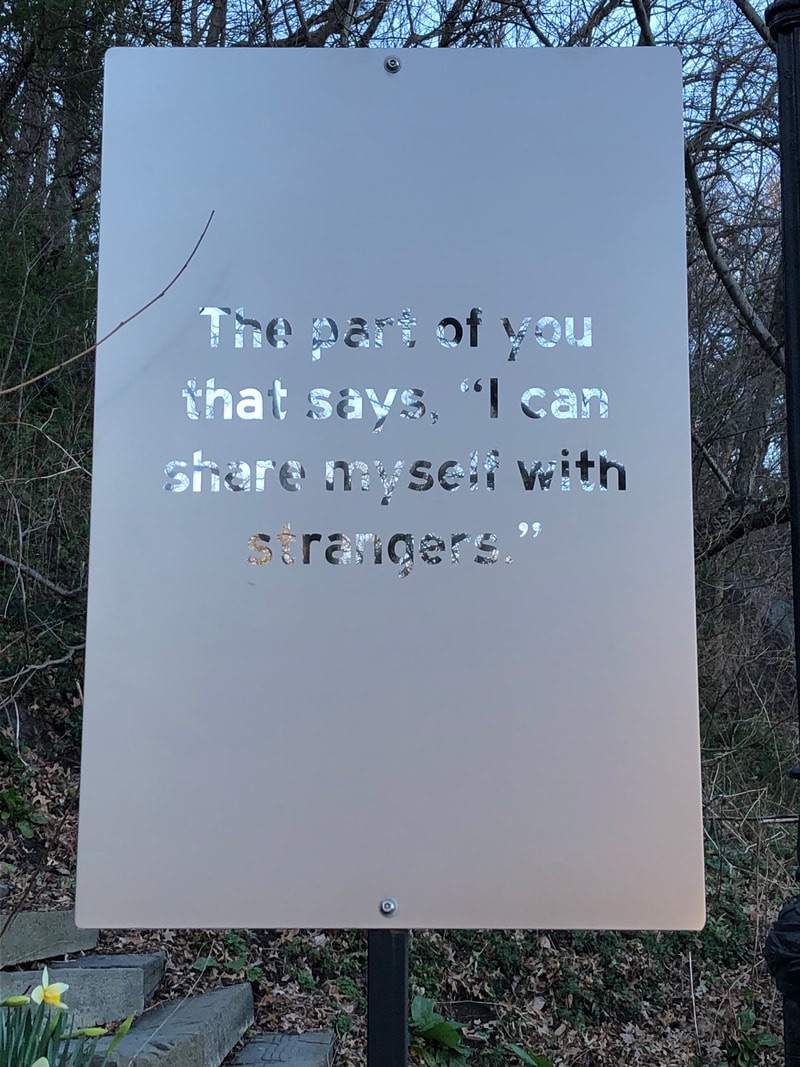

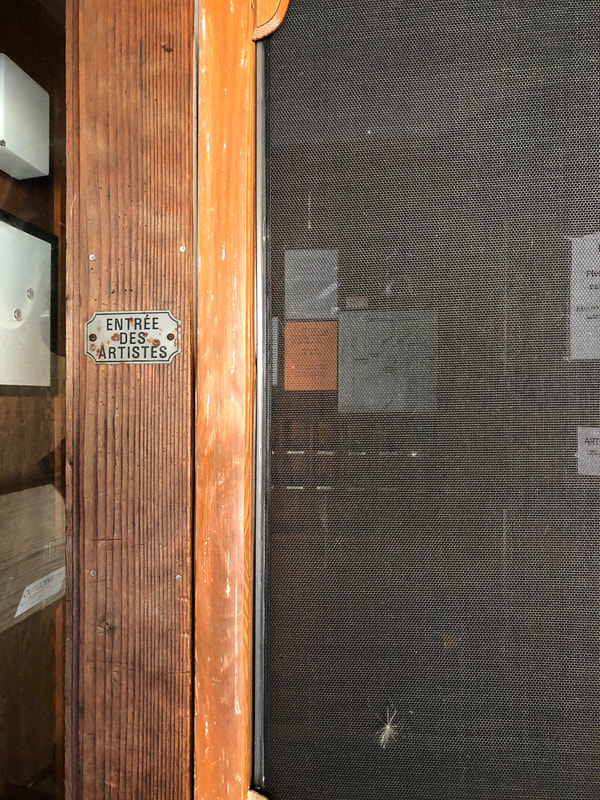

I’m here. I’m writing this in my studio. I’ve walked many of the trails but not all. I’ve eaten lots of wild blackberries and I’ve fallen in love with wild fungi all over again. I have snake envy – I haven’t seen a rat snake yet, others have – but I’ve seen six turkey children walking single file, with a parent leading and a parent watching the rear. The summer in the Northeast is humid, so damp meets every sense and movement. And summer insects dive into my ear, not nice. The other artists here – two visual artists, an architect, two composers – are fascinating and about the ages of my children. Our difference in ages should not be relevant, but, inevitably, it is, as we chat in a present that moves malleably and sometimes awkwardly between our incommensurate has-beens and will-bes, with varying curiosity, distance, learning, and perhaps even irritation. All fully vaccinated, we agreed to be a pod and moved from personal fear of Covid to personal fear of Lyme disease. Our artist group seems to have adopted ticks as our fear mascot. I finished reading a manuscript I was scheduled to send to a bookmaker in Berlin who is working with me to create an artwork edition of my first novel. Conceptualizing the design and working with him has been a creative adventure in its own right but it doesn’t consume and stimulate me the same way writing can. I still was not writing. One of the other resident artists pulled the Hanged One tarot card for me and that led me to let something go. Somewhere in that swirling, giving up was giving up expectation and failure. I’m small. Start small. Was this what writer’s block is? I haven’t had writer’s block before this, at least not enough to be named as such. Writer’s block or not, my state seems larger (though I am small!) than my writing. I’m stagnant between the course of my pre-Covid life with its logics, joys, fractures, and morphoses; and now – is it a post-covid life? – with everything thrown into question, a state of dreamlike precarity, with an insistent will to joy, but a seductive fatalism in one corner that sometimes looks like a comfortable resting place, and sometimes is a narrow, romantic, nihilistic acquiescence to death, to nothing. I’m well in the second half of my life and Covid amplified what older people experience more commonly, I think, than younger people – mortality. Death threatens meaning. Forget the course of it, I say. Treat this state, I instruct myself, as a beginning on a new plane, no more nor less than the last, but different. I don’t have to know what this blog post will open as my first new writing of any length and significance since February of 2021, this dodgy time of post-Covid-still-Covid. It may not open anything. It may just be a whistling not-yet-a-tune that knits once more my cut-off, cut-down selves that are held within my safe-enough and healthy-enough body; though sometimes I think they float around me in words or feelings, all in a complex world of pain, joy, horror, love given and received, love walking away, walking away with love (to quote Abbey Lincoln). The will to live, the will to love, the will to death, not only once, not necessarily in that order, haphazardly out of our control. Deflated, defeated, laughing, loving. Writing. Hear me: I am alive, to be me, to do this writing now, committed to living which extends

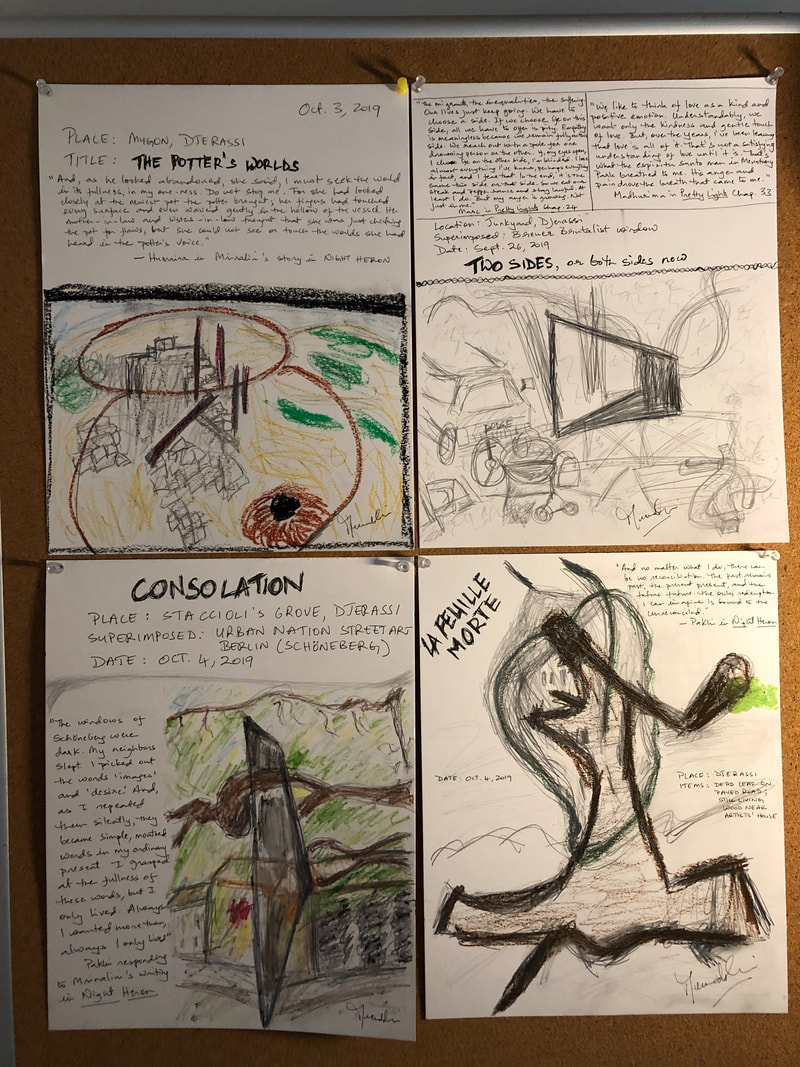

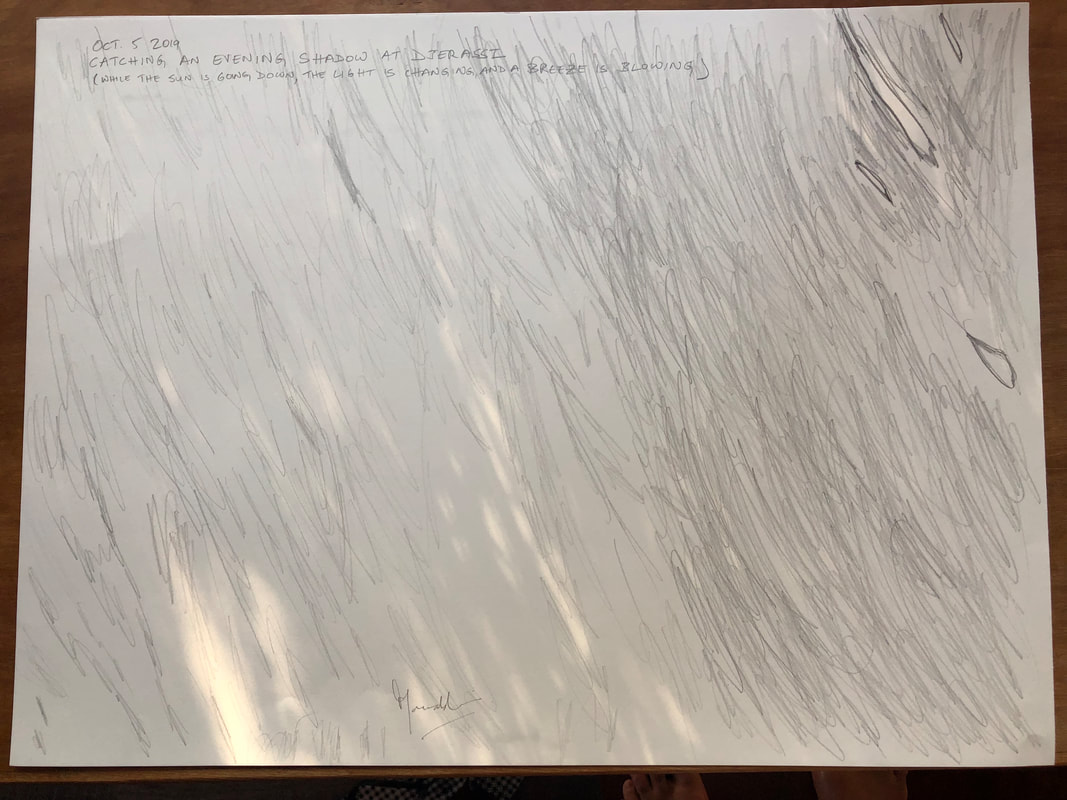

A month ago, as we were told to retreat from public life in NYC, I found people, including me, staying out more widely and gathering more, and more densely, than the warnings called for. Then slowly New Yorkers, including me, retreated to our neighborhoods and then to our homes. As we did this, as an individual I worried specifically about loved ones and more abstractly about the scale and effects of this impending cataclysm. My family and loved ones live on several continents, some of us alone. I live alone. Like many other people I’ve learned to increase my use of messaging, phone, and video for mutual care with family and friends. Some people living alone feel lonely. I have a very high tolerance, and even need, for solitude, so mostly I don’t feel lonely, but the current form of my solitude – distant, with no physical activity of care for others – is also a building block for my bubble. In contrast to my situation, some people and families, especially in the small apartments of my city, contend with the everyday struggles of being constantly closed-in and crowded in small spaces. I live in West Harlem in Manhattan. My neighbors are primarily Latino and African-American. My own coloring is just about halfway on the range you see in my community. I’ve lived here almost two years now. From the beginning I’ve loved that people commonly speak to me in Spanish, at least until they see my goat-in-headlights expression. Before COVID19 lots of social life in my neighborhood happened in public spaces. Groups of all ages, but especially older men, and sometimes older women, would gather on or around a few chairs on the wide sidewalks of Broadway or on the small patches of green in the neighborhood; or they would gather on and around the benches on the divider between the two sides of Broadway. It was common to hear music, usually with an African-American or Caribbean rhythm. Quite elderly people – some disabled – were given place and engaged with in these public spaces. This was not some idyllic world. Most people looked worn. Many looked busy. Some frowned. Many looked intent, even worried. But I noticed and loved how familiarity gathered among people who live and work here and slowly I started feeling allowed to join in that gathering of familiarity. I have never felt unsafe in my neighborhood, even returning home on foot or by bus or subway after midnight. As COVID19 became more clearly, more palpably, a threat, we were told to stay home except for essential services (health care workers, transit workers, EMT and FDNY, police, grocery store workers, pharmacy workers, postal workers, trash collectors, and so on) and essential activities (grocery and pharmacy shopping, exercise). At first my neighborhood seemed barely changed. The old men continued sitting in their chairs and chatting, the young men played basketball at the recreation park not far from my home. For the first few days the sidewalks did not look hugely different from pre-COVID19 days. Slowly that changed. People continue walking up and down my street, but fewer, with more distance, and increasingly with masks on. People go to laundromats, people need to get food, people need to get away from crowded homes, and people – essential workers – go to work. Over the last few weeks most of what I see is from my closed second-floor window (it’s still cold in NYC) or on my walks to the grocery store or post box, or to the river for fresh air, beauty, and also to be with people though we keep our distance. Last Saturday, a young man, a stranger, delivered our mail. Our usual mail carrier is a young African-American woman who was assigned this route (to her delight, she told me) about the same time I moved in. I started wondering why this man delivered the mail and when I saw her again a few days later on my way to the river, I exploded at her with relief (from a distance). She had taken the day off to be with her children and family. So what am I doing behind my closed window, apart from looking at my neighbors walking up and down my street and clapping at 7 pm? Lots of phone calls to people around the world who are concerned about me, and whom I’m concerned about. I speak to my mother in India every afternoon. Almost every day I have contact with each of my grown children who are making their own adjustments to living with COVID19. All my consulting work in conflict resolution and leadership development – in any case no longer my primary occupation – is on hold. My primary occupation is writing fiction. I am trying to get my first two novels published, and have been reading in what I considered my fallow time before I start my next novel. Often I veer off to read and watch the news, including NY Governor Cuomo’s press briefings. A few times a day I get mired in my Twitter feed. Mostly my engagement with news and Twitter is a kind of frantic spectatorship. I look for places to donate to and donate, both to organizations that will provide resources to those most hurt and political campaigns of people whose values I support. Because of my recent divorce, I have some money I can invest so I watch the stock market, somewhat bemused. A faint guilt permeates the time spent watching the stock market and remains under the surface. Then I tell myself, better me than those hedge funds and rich people. But the faint guilt remains. I rule out certain industries and companies. But the faint guilt remains. We are all complicit in the economy. Some have less choice. Some have less effect. Some gain. Some suffer a lot more. Some don’t care. The faint guilt remains. Starting a month or two before COVID19 affected me directly, I've noticed a storm gathering within me regarding my third novel. In the greater solitude of this stay-at-home time the storm signs have become more urgent and I’ve been trying to figure out whether it’s time to chase that storm, and, if so, where to get close to it, how to engage with it. It’s a very large storm that’s been gathering, about all of life, which means life all the way from the quivering inside from where we are subjects, objects, heroes of our destiny, and beaten down. I’ve loaded my jeep and I’ve started out to chase this storm. Meanwhile, in numerous phone calls and messages I’m asked, “How are you? How are you in NYC?” Friends and family worry about me and they see me as touching, directly, the frightening tragedy they read about in their news media and see on their televisions. Inarticulately I tell them, I’m in a bubble. I feel like I’m living in a bubble, I say. I feel like I’m living in a bubble in a location of immense fear and distress. That’s all I’ve been able to say. I haven’t been able to, I can’t, claim more than that. Concurrently my internal storm is getting larger and more compelling. I’m closer to it. I’m ready to start writing again. Then, in the last few days, two things struck my bubble. Not bursting it, mind you; this isn’t a heroic story. A friend who works with very low-income women and girls in Kolkata sent me The Guardian article called A Tale of Two New Yorks. Yup, I know this, there is no hiding was my external response. Yup, we can’t hide from this anymore was my internal response, with a distant cynicism about what we can hide from given a little time and self-serving distraction. I turned to follow my internal storm. The second thing was my experience at an open mic program organized a couple of evenings ago (April 10) by Under the Volcano, a superb international writing workshop program in Tepoztlan, Mexico which I had attended in 2018. When the announcement and invitation to sign up arrived in my inbox, I immediately responded and got a spot. In Tepoztlan, two years ago I did my first open mic reading; I chose an excerpt from my first novel, narrating the main character’s frenzied turning inside out while painting. At that time I was in the beginning stages of my second novel, so for April 10’s open mic I decided to read an excerpt from my second novel which is about memory, identity, and the internet. The novel is also about love, anger, and difference, but for my three-minute slot I chose a piece that is rollickingly about coding, gaming, hacking, and AI. I love that piece, I still do. But when I heard a young woman in the Bronx read her piece I hit my bubble. Inside, outside, all of me hit my bubble. In and after a texting exchange with another participant after the open mic program, I continued to bounce in and off my bubble. Then, yesterday, another friend sent me the same Guardian article referenced above. With the repetition and given my experience at the UTV open mic, just knowing that two New Yorks exist, already knowing, did not exhaust my internal or external response. I immediately wrote the paragraph below and sent it to the friend who’d just sent me the article and a few others. This is at the core of my bubble: “The public advocate pointed out that 79% of New York’s frontline workers – nurses, subway staff, sanitation workers, van drivers, grocery cashiers – are African American or Latino. While those city dwellers who have the luxury to do so are in lockdown in their homes, these communities have no choice but to put themselves in harm’s way every day.” I see that every day in my neighborhood. I know that my going out won’t help, in fact by increasing density will raise risk for everyone. So I stay home, doing work nonessential for my city in crisis, in many ways unconnected to my city in crisis, in some ways – if I gain from that benighted stock market – gaining, how can that be possible, gaining while my city is in crisis. The question is how do I connect my work, my living with this reality: how do I connect life inside me – that storm gathering – with life outside me? This blog post is one start to addressing that last question, amplifying the question, looking at how it rises both outside and inside me. I do not touch the distress of my city directly, but, in my bubble, I am part of it. This is not an ending. There is no resolution here. The inequities that exacerbated the unevenness of tragedy in my city existed before COVID19. The communities that have been asymmetrically affected by illness and death are likely also to be least helped by recovery efforts, least strengthened for the longer term. I can’t just be appalled. I can’t forget. This is a long game, not a short-term wringing of hands. Added perspective: This blog post focuses on my bubble in NYC where I live, but the bubble phenomenon is countrywide, worldwide. In the U.S., race and color add an enormous burden, but low-income people everywhere serve more and are served much, much less. Added comment: This was a difficult piece to write. It’s hard to reveal privilege even to myself, because a significant amount of privilege is unfair; I want to be “good.” But it’s much, much harder to live (and die! to see your loved ones die) without genuine equality of opportunity, equality of access to wellbeing, and equality of access to community resources in times of need. When I was young, I often fought for fairness, but I learnt slowly that life, often enough, is “unfair.” Getting old, I know life is “unfair,” but I’m learning that if I cut myself off from directly engaging with life outside me, I become emptier inside. In my case, directly engaging with life outside me means not turning away from being appalled by unfairness that I’ve always known; from my own confusions, complicities, and complexities; and from attentively, cannily choosing fairness and equity more and more rather than less. In practical terms, the last means supporting adequate wages and income security for minimum wage/hourly/casual/gig workers; easy access to health care information and services, including health insurance that is affordable or free where needed, but also specific systems in place for outreach, health education, and diagnostic and preventive services; attention to environmental health hazards, including housing deficiencies, work conditions, and inordinate production and marketing of junk foods; equality of opportunity in education which means explicitly lots more effort for children who don’t grow up with income-/class-based access and exposure outside of school systems. These are obvious ongoing things. Crises will come again; climate change is looming. In crises, the first question must be: what extra attention must we pay, what extra must we do to protect people with the fewest resources, in places with the fewest resources, who are often also most at risk? We must be prepared for this question, that extra. In a crisis we are all appalled. When this is over, how will I continue? How will you? I am coming to the end of my first artist residency. I’ve been revising my second novel, Pretty Lights, sometimes triumphantly, sometimes with a deep insecurity that it, my writing, will never be widely liked. I’ve also been drawing, at first as play, then increasingly with a seriousness that I have grown to cherish. And I’ve been walking a lot, on an average three miles a day. I had not known that a residency could be a space of such creative work and beauty. Four weeks ago, I flew into SFO and was driven here along with another artist, Beatrice Pediconi, a visual artist. On that drive she said two things that foresaw the shape and future of this residency for me. First, somewhat sternly, or perhaps she was just tired from our long and delayed flights from New York, she said that artists are here to work and don’t disturb each other. When she said this, it sounded almost monastic. I wasn’t intimidated, more curious. She also said that she does one residency a year. Now, I want to do the same. Another writer, an established author, had told me about residencies about five years ago. They were places of work and community she told me. She sent me her list, and Djerassi was on that list. At that time, with my other work and family life, a residency had seemed a complicating luxury. Then, after my first foray into a formal program for writers, Under the Volcano in Tepoztlan, Mexico in January 2018, I decided to apply to one residency. I was still living in San Diego and didn’t want to travel far. Djerassi looked beautiful and I loved that they mix artists of different kinds. Of course the chances of my getting selected were slim, though I didn’t know how slim until I got in. Soon after applying, my marriage started falling apart for reasons unrelated to the application, at least on the surface, though no doubt there were resonances from my writing into and out of the fault lines in my marriage. I got the forwarded hardcopy notification from Djerassi just a day or two before the deadline for responding, when I was already settled into my new life in New York City, that of a single woman claiming “writer of literary fiction” as her primary professional identity. The letter arrived like a soon-to-expire password to the new level of a quest, and I carried it like a child’s talisman, opening it on the subway and elsewhere for the rush of pleasure it gave me. So in the second week of September, I came to Djerassi, a few days before my younger child’s twenty-first birthday and my own almost-sixtieth birthday. I had just parted ways with the publisher who’d contracted to publish my first novel this fall. It was a late – and painful for me – parting that we mutually agreed on as it became increasingly clear that they wanted to publish a novel quite different from mine. Djerassi had been the first major acknowledgement of me as an artist. Now it remained the only major acknowledgement of me as an artist. But I came to Djerassi more confident of myself as a writer than I’d ever been and I’m leaving more confident of myself as an artist than I’ve ever been. My decision to withdraw my book from Speaking Tiger was remarkably without rancor. The decision was clear. I am not averse to further revision or editing, but I know now, quite profoundly, that I can only revise for a better version of my novel, not simply for a novel the publisher wants to publish. One day those will coincide for my work, but at this time Speaking Tiger and Night Heron are not a match. I came to the Artists’ House, the main house with old rooms, shared bathrooms, a lovely large kitchen, and views of forest, redwoods, ocean, dry grasslands, and variegated hills. The beauty starts off stunning as I drink my coffee on the deck in the morning, enwraps me through the day, especially on my long hikes, and closes with spectacular sunsets almost every evening. The few days we had a foggy cover come in from the ocean, the greens turned dull and a kind of gloaming settled on the day. I came to expect day after day of light, shadows, shapes, nature, and art. My last new walk – also beautiful, though the most ordinary, indeed the most dull – made me realize how addicted I’ve become to the quiver of sensory, intellectual, and emotional response to striking beauty. This addiction and its sources have run through my knowing and claiming every part of my creative work here – dreaming, writing, revising, drawing, experiencing shame, speaking about shame, researching my next residency, planning my next round of submissions, staring at the breeze – as work. Every one of us here worked. To my knowledge, every one of us worked every day, including over weekends. This was not vacation, nor was it a retreat from work. It wasn’t put-your-head-down-and-create-a-monetizable-product work, though all of us would want to earn from our art and for some of us art is the primary source of their income. It wasn’t work simply aimed at an externally demanded deliverable,* though all of us would want others to read, or see, or hear, or watch our work and feel some of what drives us to make it, perhaps remake it from their own history of being, perhaps think something new, jumping off a moment of the phenomenon of our work, and jumping into some wide mindscape of their own knowledge. Here at Djerassi more than ever, I deeply sensed, felt, and recognized how in the quivering process of creative work, art connects the deeply introspective – the interior and idiosyncratic space of living, being, sensing, feeling – with the world of historical time, of physical phenomena, of conventional forms and social understanding, and of the imprecise emotional lives of sentient beings who live together. The Djerassi program gave me almost constantly beautiful space and expansive time. Among other goodies, Chef Dan cooked us dinner every weekday evening, and our fridges, fruit baskets, and bread baskets were always full. My ten fellow artists – three visual artists, a composer, a choreographer, and five other writers, including a poet and a playwright – helped make this an intensely creative workspace for me, one of productive solitude as well as sometimes easy, sometimes intense interaction; artists at work as well as a community of artists. My fellow writers challenged me shockingly, shockingly productively. I am particularly grateful to the visual artists for letting me see some of what they see. And quite apart from the space and time it gave us, I am grateful to the program for inviting us to conceptualize an outdoor artwork (which I greedily assumed extended to me, a writer) as well as requesting from us an “artist’s page” as a small representation of the two-way gift between the program and each of us. These invitations led me first to conceptualize a Brutalist window – mimicking a window of The Met Breuer building – between the Djerassi junkyard and the forest beyond it, a reflection on the ineluctable immanence of two sides, indeed of a general integration. In this piece and three more that followed, I experimented with visually representing some passages of my writing. Emboldened by these efforts, I then experimented with creating a visual piece with no connection to my writing, indeed with no prior content intention at all. To me this piece is naïve art and delightful. Djerassi has been a place where I can work with intensity, seriousness, excess, and naivete. In many ways, my time at Djerassi was rather like falling in love for the first time. I close with deep thanks: to the Djerassi program for selecting me and placing me with this group of artists at this time; to my fellow artists for introducing me to new ways of thinking, feeling, seeing, hearing, grieving, and even laughing. I loved the mountain lion spirit that came into our group early, and then stayed with us. And, of course, many, and big thanks to all of you – artists and staff – for making my birthday this year one of the best ever! Below are some photographs of wild life and cattle who also charmed and shaped my life at Djerassi. And at the end are two videos that convey sounds of the wind when it blows. . * Some of the artists worked to deliver on commissions. Months ago, a friend was stricken by the finitude of life and fear of regrets. We talked about this urgent – galvanizing rather than paralyzing – fear of life ending. I couldn’t empathize because I have not feared death in a long time, if ever. I have feared disability, which could come with age but also unbidden from accident or disease; and, in particular, I have feared, immodestly, the dulling of my fine mind, but fear of death? No. We quickly and lightly attributed the difference to my Hindu, rather than Judeo-Christian, upbringing. I have often said that I don’t have to do everything in this life. This does not mean that I believe that I will live another life, just that more lives than this life of mine will be led. So rather than the end or regrets at the end being important, it is – most tritely – living right now, “this is what I want to do, this is who I am,” that has been important to me. This is a frame that has served me well, as I have genuinely enjoyed a little patch in a concrete path that looks like a woman dragging a sack behind her, and, less whimsically, was consumed, with awe, by a storm of jellyfish, thousands if not millions streaming past me, a few stinging my face. These are sensory joys. In each case, it was not just an image, or a sting, but, with the concrete it was the feel of the light, the humming of a high-voltage wire above, and in the water, again, it was the light, or lack thereof, the awareness of gristle – Silky Shark bait, in the water amidst the swarming points of light – that I could not smell. But the gentle joys of the moment are not only sensory. Words can snare me, not just their rhythm, though, admittedly, it’s their rhythm that typically lures me first. Ideas can make my eyes widen, my fingertips feel alive.

In this way, reading The Paris Review’s interview with Luisa Valenzuela, whom I met in Tepoztlan in January, and chose to adulate though I didn’t really know her work, or her, led to a gentle moment with “the badlands of language,” from whence, according to Luisa, women come. Reading that phrase, I wanted to own it, not possessively, but gently, like the jellyfish stings and flawed concrete. I, a writer, come from the badlands of language. What does that even mean, as one of my daughters would ask. It has something to do with anger, I think, something to do with the paradoxical freedom of someone who struggles, who fundamentally is not and can never be free. We cannot just be the flower that offers its beauty and perfume freely, indeed the flower does not do that either, but that is a tangent I will leave aside in this piece. Learning to gently enjoy the beauty of the moment is truly a source of peace and wonder, that – as I let the beauty of this moment, of writing this piece with morning light falling on pictures of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Ray Charles; falling also on a postcard of one of Do Ho Suh “houses;” and, above all of these, falling on my collage of Thomas Hirschhorn’s ruins in Zurich – relaxes my body. I rub my cheeks. The beauty rubs on to me. This is a benediction. But my life, coming from the badlands of language, in many ways quite literally, is not only benediction. Realizing this is not gentle joy. Indeed, it returns me to wildness, to wilderness. The Silkies never came, the gristle got caught in my hair. As I write this, the morning light is lovely, but cortisol, fear, and desire are in my fingers as well. Cortisol, fear, and desire are not gentle; they come from struggle. Struggle is wild. The flowers are not free. I have already written from that wildness (read my first novel!). How do I live with it? How do I hold it as preciously as the gentle joys of each moment? It calls for risk in living. Does risk in living mean risking loving (as my first novel explores)? When the end comes, there is no happy ending. There is just the limited end. Everything else goes on. Struggles and projects remain unfinished. I, with a happy Pollyanna-ish mind, want to end this piece with a call for, a touching of, a blowing out of the “joy of loving.” That phrase wrote itself into the title and I am loth to throw it out. But the joy of loving is what it is. You can only have it if you have it. And otherwise, or rather in any case, you struggle. Note on jellyfish photo: Our guide and underwater photographer did not photograph the swarm. These jellyfish, also lovely, also stinging, also amid the flesh and bone of the shark bait, came before the swarm. Epilogue: I’m going to dive again. Every moment is a dying moment and a new beginning; every day a new year starts. So paying attention to the end of a man-made calendar year invites irony even while it draws benediction. Mulling the non-binary lying of benediction with irony – both benediction and irony have fluid shapes and fuzzy boundaries, for example a metaphorical image of irony as large polka dots imbalancedly in a variegated mess of benediction, or vice versa, seems entirely plausible – in the last days of 2015, I realized that this is a fundamental state of human being, wrought as much into writing – whether penny-dreadful Harlequins or immoderate literary fantasies; the range, shapes, and tones vary – as into my everyday life of elemental love, conscious good, and whiplash cynicism.

New paragraph. Long an admirer of Pollyanna, I love to hear the ways people love and are kind to themselves and others. For many years this was a practice I sought. At first I struggled to keep all of me, the cynicism, fear, shame, and anger, along with the love and kindness to self and others. And then the struggle stopped, not because the love kindness cynicism fear shame anger disappeared, but because the struggle, petulant, distracting, or sucking me into an abyss of perfection, was getting me nowhere. So that was resolved in practice. But not in my writing. Writing under my nom de plume, which is my nom de nom which is my legal name, memorializes me, or, at least, memorializes my name. So I want beautiful, inspiring writing to throw lustre on my name, but what I want to write is often, mostly, flat, ironic. Be careful; I’m not just peer-pressured into wanting to be inspiring (or flat-languaged). At a gut level, with a final constancy, I love the inspirational. But when I even think of writing with singularly inspirational portent, my lips turn down. Can’t do it, can’t do it, don’t want to do it. I like writing flatly, ironically. I want to write, with round eyes and a flat tongue, the ironic underside of benediction. But (third time, third time lucky) surely I can write blips of gratitude here, offer genuine Pollyanna puffs of contentment for love in my life, for being able to write the words I want to write, for being able to drink wines in the evening, and fragrant coffees in the morning, indeed for being able to smile at the strangers who are laughing, swaying, and being silly in front of me. This gratitude curls away from irony. In the spirit of this gratitude, then, … All of you, those who have opened this post, those who have not, and everyone who does not know it exists: As this moment dies, this sun-day ends, this calendar year draws to a close, I wish you comfort with, or at least respite from, your cynicism-fear-shame-anger, I wish you safety, joy, and good health in drinking and eating (so many of you will not have the safety or the good health or even the potable liquid to drink or food to eat, but, still, fiercely, I can wish this, I can deny the irony of this helpless benediction), And I wish you love to give and love around you, even if unspoken, even if love is simply the mundane sloth of mourning doves on the wall. Recently a San Diego-based colleague and friend invited me to sit at her table for the local celebration of National Philanthropy Day. I found myself wavering about whether or not to accept the invitation* because I assumed she had invited me as a dialogue and leadership development practitioner, a role I am downsizing, and not as a writer, a role that still feels baggy around me, that I am still exploring, and that didn’t seem terribly relevant to the purposes of the event. A few days after the invitation, I had the opportunity to discuss my professional-identity-related ambivalence with her, and, in addition to being slightly puzzled by the intensity of the question (a puzzlement I heard from others as well, mostly in the form of “who cares”), she told me she’d invited me as a “philanthropist” to celebrate what I and others contribute, to our region and world, in whatever ways we do – with money, volunteer activities, dialogue work, writing. I was delighted by the large ontological frame her use of the epithet “philanthropist” constructed for my different professional identities, indeed, for all my identities as a social being.

Mentioning this delight to another (not-San Diego-based; indeed fabulously global) friend, I initiated a prolonged argument on the meaning of philanthropy. My easy adoption of philanthropy as an umbrella that would encompass my various professional and personal identities was vigorously rejected on the grounds that philanthropy has a strictly technical meaning that separates it from its roots in the massive sloshing phenomenon of human-love-for-human, a vast not-misanthropy that exists beyond an imaginary zero line. I didn’t waver. Nor did she. We ran out of time, so the discussion ended. Eventually, somewhat gleefully, since my philanthropy is larger, at least in conception, than her philanthropy, once my cortisol level dropped, I let it go. So now I return, non-polemically, happily higher on oxytocin than on cortisol, to imagining writing as philanthropy. Does it work even if my writing is not intentionally philanthropic, as it often isn’t? A sentence pops into my immediate response, drawn from Ben Jeffrey’s review of Michel Houllebecq’s dispiriting novels “… if it feels true, it will be better writing than something that only feels like it ought to be true—literature isn’t essentially normative.” There’s a piece of my answer in there. But writing as philanthropy calls for a whole blog post of its own, so more on that another time. * It turned out I wasn’t free at that time. The small girl stared at the scolding woman, gradient of seventy-five degrees. The small, but bigger than the girl, boy stood to a side. The woman turned, too quickly for the boy to change his expression or disappear. He looked at the floor, sideways at the girl, as words poured on him, as if spouted by a generous mouth offering potable water, without cease, in an old French town. The little girl stuck a thumb against each nostril and flapped her hands at him. He frowned and earned a louder barrage, without punctuation, commas periods falling away. Now the woman turned this way, now she turned the other way, and the children exchanged grimaces and tongues out and waggling fingers. At last, the woman stopped, waved her hands threateningly, then uttered a brief phrase, and walked out. The children dived under the bed, and poked and squabbled and laughed. The woman returned. The children fell silent. “Where are you?” the woman asked, and started scolding again. The girl rolled her eyes and made a face. The boy tickled her. She started shaking with laughter, soundlessly, and watching her, he started giggling, soundlessly as well. “Idiots,” the woman said very loudly and left again. The two children continued to giggle in silent spasms until one coughed up a drop of bile. And then they laughed out loud. For many years.

Hmmm…. Laughing out loud, real, unaffected – no irony, no falseness – laughing-out-loud is among the most ecstatic experiences of being alive. So should I, could I, how should I write LOL prose? I find this a hard question (as in, the answer is not obvious) and a difficult question (as in, this question is likely to require looking blankly at a dead end, in other words, inadequacy). Most often, what makes me laugh out loud is self-shiftingly vulgar irony, and so I fluctuate – though with very little shifting, of self, or anything else – between mumbling internally, “I can’t write that kind of prose” (as in, I’m not a comedian, which, I tell myself, is a non-literary figure, for the most part), and mumbling, perhaps externally, “I can’t write that kind of prose” (as in, I’m not clever enough to write that kind of prose, especially since prose means restricting my palette for vulgar irony to one medium, words; in other words, no sound, no smell, no grimace, no gesture, no pokes, no mirror neurons, no palpable, malleable time, or, if any of these, just a little, a blotch, a line, in very limited registers). If I could draw, like Nicole Hollander, for example, this’d be a different story. (or) Perhaps not. Emojis help. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed