|

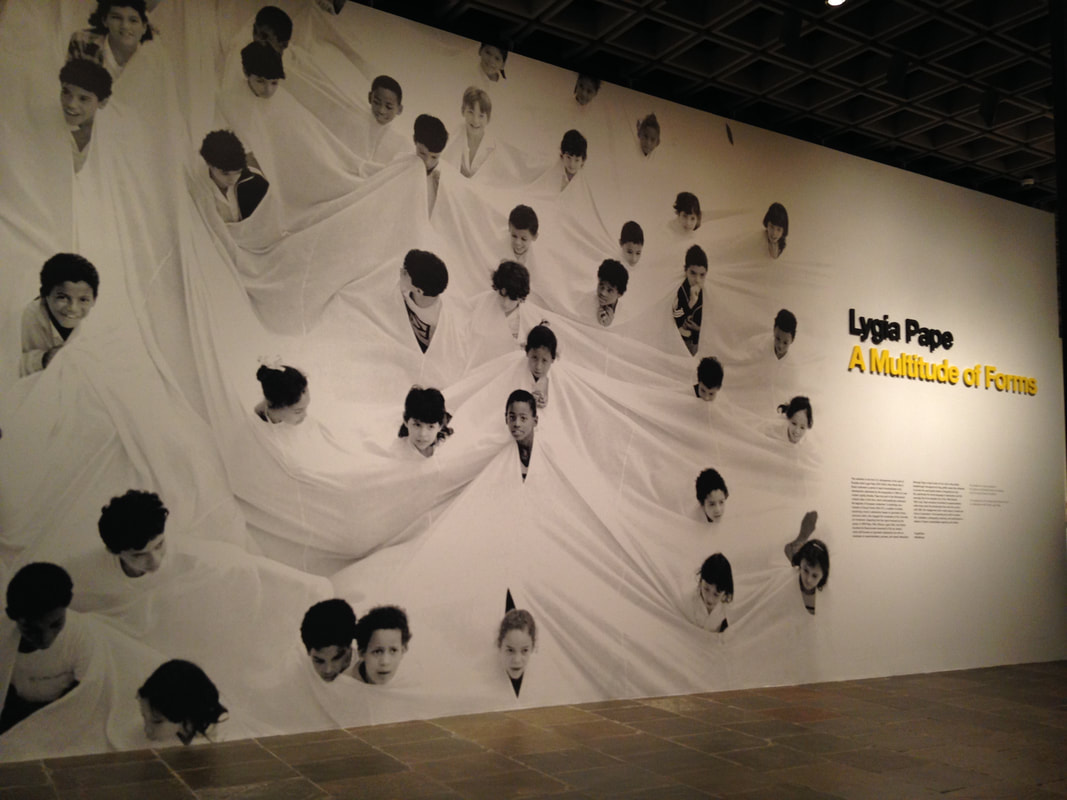

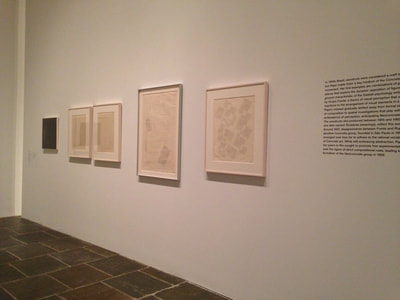

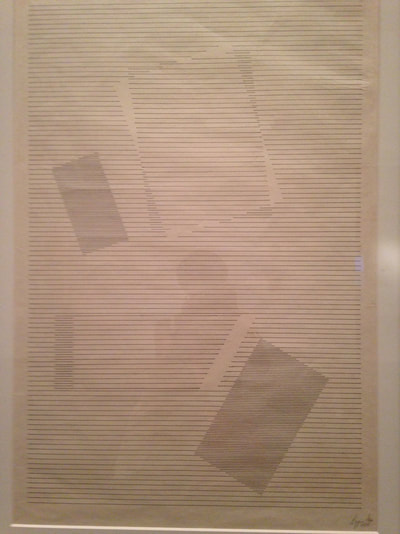

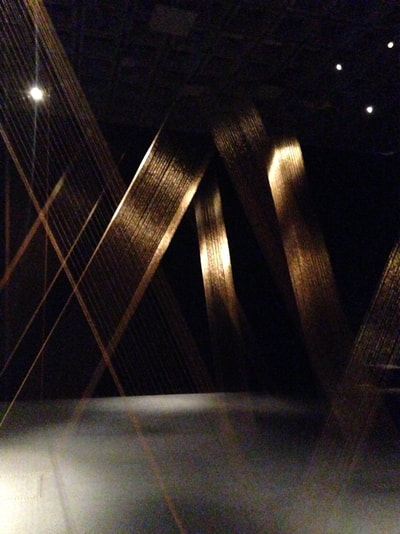

In the past it appeared that the engagement intention of art was to conjure a single bond, however illusory, between the viewer and art object before her. Supportively, the role of a curator was to present the art object in the best way to achieve that singular moment. Contemporary art, which seems loosely to be art created over my now-rather-lengthy lifetime, appears to have different and broader intentions, or perhaps these intentions have been laid upon it by the accelerated popularizing of art and the bolder actions of curators.* The curator in contemporary art seems to have developed into something between a composer and conductor, who orchestrates a dynamic multi-sense, multi-directional engagement between the art, context, and viewers, and invites the single viewer into a kind of performance which they** can choose to enact somewhat hermetically amidst wraiths, or somewhat chattily among other willing or unwilling members of an expedient ensemble. My most recent experience of contemporary art-watching happened in New York City, with a prelude visit to the Rubin Museum which presented “historical” objects in a winding, resounding, compartmentalized, but also fundamentally open and flexible, space. I went to the Rubin for the Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition and was properly astounded by the intensity of each photograph, each a composition by itself. I left the Rubin struck by the Buddhist iconography and sounds of the museum, which enfolded the more traditional presentation of the Cartier-Bresson photos, and conjoined easily the meditative, the erotic, the powerful, and the immanent. One could have chosen to visit only the Cartier-Bresson exhibition but that would have meant a deliberate shuttering of the senses, or an excision of a limited exhibition space – its photos, air, light, and walls – from a larger composition.*** The visit to the Rubin was a part of seven days of walking, working, eating, talking, thinking, and feeling in the city. The walking (around Williamsburg, the Village, from midtown to the upper west side, loitering, speeding, jostling), working (resisting and learning how to pitch and sell my first novel), eating (patatas bravas, Singaporean street food, Korean fried tofu, street dosas, a street hot dog, cauliflower tacos), talking (about politics, change, love), thinking (about strategy, living, composition), and feeling (the humidity of NYC summer, the grittiness of dust and burnt fossil fuels, the rhythm of slowness and speed sometimes under my control sometimes not) had inflated my sense of being, had created a sense that I had more, and more alive, nerve endings on a larger surface area. Wrought by this urban stimulation I went to see the Lygia Pape exhibition in the Met Breuer. This long, wandering introduction to a deliberate exhibition in an angular building is because my engagement with the Pape exhibition was primarily about movement; and movement implies, indeed requires, space and context. I went into the Breuer building and bought an annual membership (with a discount for being from far away), for I have been there before and will go again. Then I chose the stairs to revisit the curiously halted viscosity of Dwellings by Charles Simonds, a vestige from the Breuer building’s Whitney days. I climbed up to the floor with the Pape work and entered to a sideways view of the splash titling and image for the exhibition – A Multitude of Forms. The image combines uniformity – whiteness, children’s heads, all about the same size – and variation – in the way the white cloth dips and rises, in the very difference of each child. It is an exuberant and sobering image, conveying constraint, concealment, emergence, and movement. Only later did I realize that the image is a still from a movie which I viewed, and remember, as part of a course that included simple geometry – of the building, of Pape’s early work with the “geometric forms and pure colors” of the abstract art of the Grupo Frente; included, also, her later experimentation with naïve, semi-ethnographic film; and, finally, her return to geometry but now with pieces of unrestrained size and expression that jutted into the large spaces of the Breuer. The Breuer building enforces attention to perspective and the curator fully uses the building’s windows, ceilings, walls, and doorways to shift perspective from the singular art piece to the space, to the oeuvre, to other live bodies, to the outside in time and the outside in space, to both the merging of self through projection of self into something external and to the shocked separation of self from the exploitation of an image or a texture, both intended and unintended. My own movement was core to my viewing of this art, but, in addition, the movements of others became part of the art object in my viewing. One of the didactic plaques explains about the “Neoconcrete” tradition and intentions of Pape’s later work that “among the most influential outcomes of Neoconcrete art is the notion of an open work subject to the contingencies of time, space, and viewer participation.” It was humbling to find myself a textbook viewer of Pape’s art. I left the floor feeling like I had walked through a life, or in a long procession, more actor than spectator. Following a quick visit back to Dwellings, now merely landscape, I entered another show, THE BODY POLITIC, four experimental videos in dark places beyond an empty space: Five Easy Pieces; Phat Free; Love is the Message, the Message Is Death; and (down a corridor, separate) NoNoseKnows. In part because of time constraints, in part because the opening space seemed to offer me only two options, IN or OUT, and in part because I was already full, I gaped eagerly at the notices for each film and left the floor. Excision was easier in this geometric building than in the Rubin building.

I went down to the basement looking for an outlet to charge my phone. After an excellent cup of tea, I returned to the street, moving – mostly forward, sometimes sideways, sometimes halting, stepping back – and observing as if my path was still curated, almost as if each object was still art and I was still performing. * My interest in contemporary art and sensitivity to curatorial work has been deeply influenced by my artist friend, Patti Fox, and my curator/artist daughter, Pia Chakraverti-Wuerthwein. ** After years of railing against the singular “they,” I have been convinced that it is a more inclusive pronoun than s/he. It is also more commonly used than my logically preferred pronoun “ze.” *** I have no photographs of the Cartier-Bresson exhibition because photography was forbidden in that section.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed