|

The US media has had an exciting year. They got to cover one of the most polarized, intoxicating, and prurient of Presidential elections ever. Everyone weighed in, all the mushrooming online outlets, the traditional paper press turned online, and television. They had a photogenic – albeit mostly in a funny way – candidate and a candidate whose stolidity, some surmised, could only hide layers of Machiavellian ambition. With very high stakes and appalling new twists every few days, the relevance of and popular addiction to news spiked. As boundaries between commentary and reporting blurred, readers and watchers often found opinion crowding out information.

Already in the months before the November election, the press started getting criticism, from across the political spectrum, for editorial bias, too much false equivalency, focusing too much on relatively trivial issues, and too little on important issues of policy; for simplistically reflecting and stoking drama, mudslinging, and divisiveness; and, yes, for offering entertainment and opinion more than analysis with enough of the data and logical structure revealed to allow the reader, or watcher, to explore the plausibility of conclusions other than that of the writer or speaker. After the election, the criticisms continued, with the added critique that the mainstream press was too slow to recognize and counter the spread and effects of “false news.” The press has engaged with some of the wide-ranging critique, most often acknowledging that there were important trends that they missed, but also defending their editorial choices, including the choice to prioritize opinion even in “news” articles. On December 8, 2016, the New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet was interviewed on National Public Radio. Terry Gross, the interviewer, read a letter to the NYT by a David Langford, who expressed dismay at the “continuing blurring between editorial commentary and news coverage. In another age, the word ‘baseless’ in your front-page headline would have been reserved for the editorial page where it belongs. The Times and other news organizations should resist the temptation to… drop their conclusion into news stories. Please allow me, the reader, to draw a conclusion for myself.” In his response, Baquet chose to defend the use of “powerful language,” side-stepping the larger question of opinion dominating information in news stories. As Baquet acknowledged – “I’ve said this to a lot of readers,” he said in the opening sentence of his response – there are a lot of people out there who are frustrated about opinion-creep in the US news media, and not just in the NYT. The media are not helped by the President-elect’s orientation to information. Mr. Trump blurs information, probability, investigation, wishful thinking, and certainty in idiosyncratic and alarming ways. A case in point is the current issue of the degree and intentionality of Russian hacking and influence in the recent Presidential election. On October 7, James Clapper, Director of National Intelligence who leads the 17 US intelligence agencies and Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson issued a joint statement that the US intelligence community “is confident that the Russian Government directed the recent compromises of e-mails from U.S. persons and institutions, including from U.S. political organizations…. [And,] based on the scope and sensitivity of these efforts, that only Russia’s senior-most officials could have authorized these activities.” The Trump campaign dismissed that statement. More recently, the CIA has offered the stronger view that the Russian government aimed to promote the election of Mr. Trump. Mr. Obama has instituted a deeper investigation, in which he is supported by various Democratic lawmakers as well as a few Republican lawmakers, most notably John McCain and Lindsay Graham both on the Senate Armed Services Committee. In a small side-twist, the FBI, while not denying that the hacking was directed from Russia, is hesitant to attribute intention to favor Mr. Trump. Meanwhile, Mr. Trump has rejected the conclusions of the intelligence agencies he will lead as President of the United States and on December 11, 2016, in a Fox News interview, Mr. Trump said about the intelligence reports on Russian hacking that “It’s ridiculous…. I don’t believe it.” This is not, “I have questions, it is under investigation, we still need more evidence,” or anything like that, it is bluntly, “I don’t believe it.” So in an environment in which the media are already tending towards information-light and opinion-heavy reporting, the press is charged with covering a President-elect who has taken the prioritizing of opinion, in this case his own, to a whole new level. If information and logic are minimized to “I don’t believe it,” and “wrong” by the highest executive authority in the country, it leaves the press running behind, trying to substantiate, confirm, and correct as necessary. If in that effort to play its role of “watchdog of democracy,” the press counters OPINION with opinions, it will leave us in the electorate less and less informed and thus render our democracy more fragile. Over the last two decades, the press has had to adjust to the speed of aggregation, low barriers to spin-off articles, and overall pressure to update news rapidly, while revenues have fallen, resources and time for fact-checking, writing and editing have become tighter, and there is always someone ready to draw away your readers and audience with something – usually opinion, preferably polemical and polarizing – that is more entertaining. On October 14, 2016, Matt Taibbi, a superb writer for RollingStone, wrote a very clever and opinionated article on “The Fury and Failure of Donald Trump” in which he pointed out that the Presidential election campaigns were being run and presented as a “Campaign Reality Show” and the effect was “to reduce political thought to a simple binary choice.” When asked on Twitter what the role of the press has been and can be in relation to this “Campaign Reality Show,” he responded, “ It’s hard. The reality show format is too profitable for MSM [the mainstream media] to give up. The actors are not only unpaid, they pay us (in ads)!” The US media must do better than that.

0 Comments

Note: My rumination on whiteness and the emergence of a post-white world is not an attack on specific people, nor on “white people” in general. Nor is it intended to reify color as denoting essential characteristics; rather, I am using “whiteness” and “non-whiteness” to denote a mix of cultural, political and economic positions that are loosely aligned with skin color and color identifications. Starting around the 16th century, economic-technological and geo-political shifts were accompanied by cultural and epistemological shifts that both fed the political and economic power of European (and then US settler white) nations and drew funding and legitimacy from that power. It should go without saying that “whiteness” is not intrinsically bad, but not only does “power corrupt,”* but the standard set by hegemonic elites prioritizes both the epistemological frameworks AND the security of those identify as and with those elites.

Today, with Brexit and the election of Donald Trump as symptomatic events, we are seeing, in slow motion, an epochal, epistemological shift from whiteness as the standard of power and cognition to… well, we don’t know yet. This is a long process that started a few centuries ago as a resistance to colonialism which was the outward face of the setting in of whiteness as the ground from which knowledge is generated and assessed, as well as the ground from which power, in increasingly global terms, is asserted both beneficently and exploitatively. Globalism and globalization started with colonialism. Technological advances allowed for great increases in international trade and cultural exchanges, as well as more travel and migration. Resistance to the oppressive and patronizing aspects of colonial rule grew. And over the last five decades the decolonized increasingly claimed authority by owning and adapting the discourses and technologies of modernity. Globalism and globalization ballooned, with both white and non-white winners and losers. Interestingly but not surprisingly, the non-white winners were mostly aligned with what I am loosely summarizing as “white epistemology,” which has led to some symmetry between the nativism of non-white losers in majority non-white countries and the nativism of white losers in still-majority-white-but-likely-to-change countries. The process, indeed progress, of white nativism was heralded by Martin Heidegger, among others. Reading through the late October 2016 issue of the London Review of Books (LRB), I found Heidegger quoted in Malcolm Bull’s intensely pertinent review of his Black Notebooks:** "Our historical Dasein experiences with increasing distress and clarity that its future is equivalent to the naked either/or of saving Europe or its destruction. The possibility of saving, however, demands something double: (1) the protection of the European Vőlker from the Asiatic; (2) the overcoming of their own uprootedness and splintering." (from Heidegger’s 1936 ‘Europe and German Philosophy’) What Bull’s review does is link this early harking of the white (European/US) angst we are seeing in full flower almost a hundred years later to both a fascinating perspective on the necessary transformation of contemporary democracy proposed by the Russian political theorist, and Trump supporter, Alexander Dugin, and a pragmatic view of location-based rentiers (who accrue financial benefits simply by being citizens of economically and politically dominant countries) as proposed in Branko Milanovic’s analysis of inequality at the global scale. Bull tells us that Dugin draws on Heidegger to develop a “Fourth Political Theory” to replace the failed politics of liberalism, Marxism, and fascism, and explains: “Dugin takes Heidegger’s claim that the consummation of the essence of power can be seen in ‘planetarism’ as a reference to contemporary globalization – a moment when, as Heidegger prophetically described it, ‘the furthest corner of the globe has been conquered technologically and can be exploited economically.’ In this context, the Fourth Political Theory offers the only viable alternative for all those who, like the Russians, ‘suffer their integration into global society as a loss of their own identity.’” In Bull’s recounting of the Heideggerian trajectory which Dugin adopts, “the plight of the abandonment of being” is the necessary condition for another beginning, a greatness that “can only be realized by ‘a seizing of, and persevering in the innermost and outermost mission of what is German [MC note – or “German” is generalizable to nativist for a particular national context].” Bull’s review gets really interesting and pertinent when he moves on from relatively familiar Heideggerian territory to Branko Milanovic’s work on inequality, twisting it cleverly into the trope of birth(erism) and thence into a plausible synthesis, “For anyone living in the West who is not in the highest 1 percent of global income, there is an economic incentive to think in Heideggerian terms: to stand firm on native soil and claim citizenship rent.” Bull’s path to this synthesis bears quoting here: “…As the economist Branko Milanovic has shown, the best predictor of your income is not your race or class but your birthplace…. …what Milanovic calls ‘citizenship rent’ (the increased income you get from doing the same job in one country rather than another)…. This helps explain why citizenship has suddenly gained more salience than class [MC note: not sure I agree with this]…. In a world where geographical location is the best predictor of economic outcomes, being indigenous counts for a lot, and the natural born citizen clause attached to the presidency of the US provides a model. If the presidency is not open to immigrants, why should other jobs be? Of course, the new nativism feeds off ingrained forms of racial prejudice. But it is conceptually distinct, not least because in terms of global income distribution race is (as would-be migrants are well aware) far less predictive than location. You don’t have to be racist to be a xenophobe, for as Levinas commented in an essay on Heidegger, ‘attachment to place’ is itself a ‘splitting of humanity into natives and strangers.’” While Bull’s review takes us through a joining of the Heideggerian narrative of plight to greatness with the pragmatics of a contemporary political economy of citizenship rents, along the way introducing us to the logic of a ‘Fourth Political Theory,’ two other reviews in the same issue of LRB bring whiteness back into the frame. One provides a view of the white US (masculine) left’s nostalgia for self-fashioning by the (Walden) pond, and the other is an explicit critique of white “racial paternalism” and insidious “evolutionism” in the field of international relations as it developed in the 20th century. Stefan Collini’s review of Mark Greif’s Against Everything: On Dishonest Times surprised me by seeming completely out of touch with discursive struggles today. It is a kind and bland review that left me wondering if that reflected more about Collini or about Greif. I am mentioning the review here only because its most striking image is of a man, most decidedly a man, who must “have the nerve to look steadily [at an object of discussion] and think.” The figure of Greif emerges, according to and reflected by Collini, as an American (decidedly white) man who thinks and learns slowly by the side of a beautiful pond. Collini expresses a polite impatience at the end of his review – “but somehow this existential quest has to be made to connect up with collective modes of responding to a world in which global capital threatens to pollute the waters of the pond, build condos around its edge, and prevent access for all but the very rich.” I read this penultimate sentence of the review as residual impatience with an aging, declining trope. Susan Pedersen reviews Robert Vitalis’ White World Order, Black Power Politics, which is a critical history of the field of international relations in the United States. Bluntly, she says, “and Vitalis is blunter,… international relations was supposed to figure out how to preserve white supremacy in a multiracial and increasingly interdependent world.” The history, as told, ends with a kind of “forgetting.” Pedersen tells us: "Mainstream scholars didn’t so much change their minds about race and empire as walk away from the question. Part of this shift was generational, as ambitious younger scholars turned towards bipolar rivalry as the hot new subject of research…. The horrific racial persecution of the Nazi regime had an impact too, delegitimizing explicit racial argument within the academy…. The 1960s would bring ‘race’ back to the academy – but mostly through new African-American studies programs, not political science or international relations…. [Vitalis] wants his discipline [MC note: as does Pedersen, it seems] to understand not only how central the category of race and the structures of racism were to its founding institutions and paradigms but also to see the erasure of that history not as progress but as repression, a wilful forgetting that has if anything made it less equipped to comprehend (much less to address) the shocking racial inequities that still mark both the American and the global order." Pedersen’s review of Vitalis’ book focuses on a familiar narrative of white supremacy and racial inequities. Reading it in the narrow context of Bull’s review of Heidegger’s notebooks and Collini’s review of Greif’s thinking man, and in the broader context of Brexit and Trump’s campaign and win, I see it as more evidence of a writhing, but still long, tail-end of a flipping system, in which “whiteness” is still the face of the greatest concentrations of political, economic, and, yes, intellectual life, but is increasingly threatened by its own growing patches of flaccid entitlement and contradictions, as well as by the increasing authority of post-white voices (including voices from powerful non-white states, voices of superb non-white intellectuals, as well as voices from bodies that look white but are seeking an idiom that is different from the conventional idiom of standard whiteness). I am intrigued by the notion of a “Fourth Political Theory,” but I won’t look for it in the nativist imaginings of Heidegger and Dugin. I believe that, for the most part, the emerging epistemology will leave behind the heroic, self-inventing, white man, whether left or right, though there will always be a role for heroic self-invention in human narratives, whether inspirational or autobiographical. A post-white globalism will emerge over the decades of this century, perhaps over centuries, not without pain, and certainly not a Utopia. Many of the current inequalities of global capitalism will continue and new hierarchies and oppressions will emerge. Does this mean that we should stick with the current, known system? I don’t think we have a choice. The system is changing. And there are exciting new possibilities for equity and beauty. But there are also sobering, very sobering, trajectories towards planetary dysfunction and increasing disparity between technologically-fuelled wealth and the drudgery and deprivation of those who are late, or unable, to access the technological means of production of the 21st century. So while a post-white world is likely to emerge, we will still need to demand rights and equity for all, teach our children that a just system is possible, continue to be open to dialogue and community, continue to speak up when we see inequity and injustice, and, most vitally, continue to defend our planet. * … to quote, quite comfortably, Lord Acton who was a small actor in the solidification of the primacy of the “Western tradition” as the top epistemology in a universe of otherwise lesser epistemologies. ** Of course, it is entirely part of the process to be using hegemonic epistemology itself to understand and critique the consistencies, contradictions, progress, and eventually supersession of that epistemology! We will not be outside that epistemology until we are outside that epistemology. As a Bengali, I was aware that the second Presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump fell on this year’s Maha Ashtami of Durga Puja. As a feminist Indian-American, who has lived almost twice as many years in the United States as my early life in India, I noticed the resonance of this coincidence with a pair of paradoxes that have intrigued me since 1980.

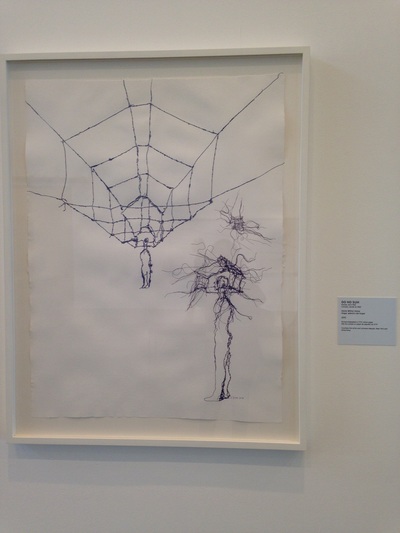

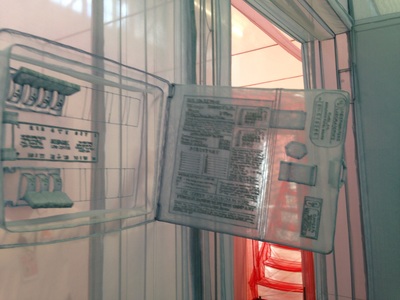

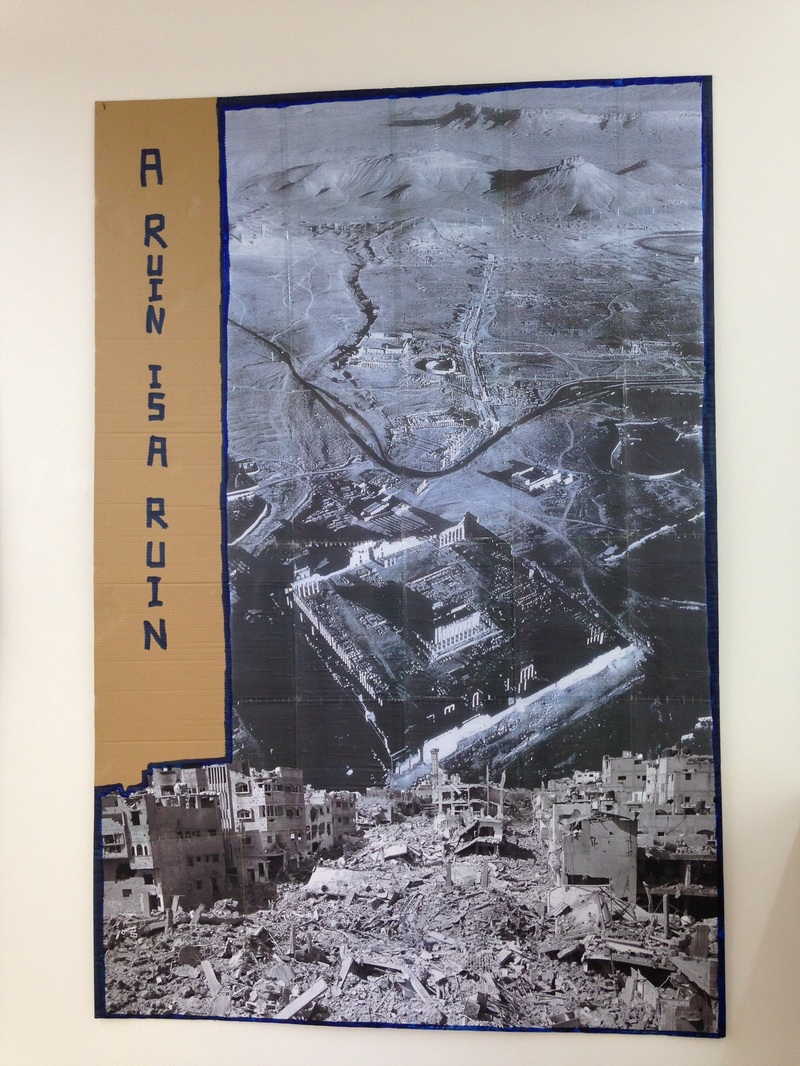

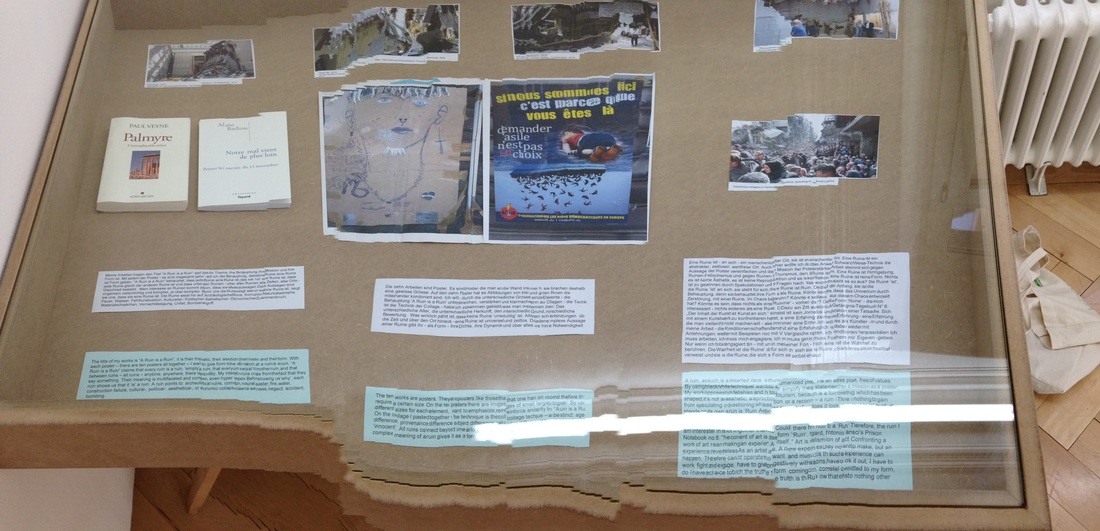

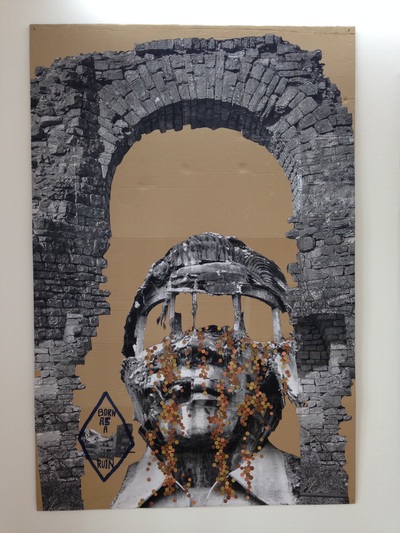

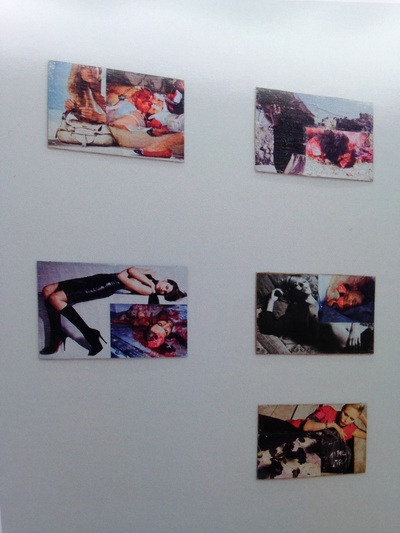

These are the paradoxes. The United States, which has a fabulous history of feminism and women’s movements, with flaws and conflicts, but fabulous nonetheless, has continued to be uncomfortable with female authority and leadership over the thirty-six years I have lived here. India which, despite its own tradition of astoundingly strong and varied women’s movements, has remained widely attached to patriarchy – with daily manifestations that range from the relatively benign passes given to sons and men to the horrors of frequent and casual violence against girls and women – has seemed to me more comfortable with female authority and leadership than mainstream U.S. culture. Starting twenty-six years ago, with occasional updating, my German spouse has said he has yet to meet a “submissive” Indian (especially Bengali!) woman. Indira Gandhi dominated most of my youth in India, but I have also seen and heard numerous other female leaders in India – politicians, businesswomen, educators, and especially fiery civil society women on the left. Today, when I am in India, I am struck by the easy ambition of educated young women, even in the midst of frequent social and professional sexism. In the United States, by contrast, I notice that, in a context where more women are graduating from college than men, highly accomplished and evidently ambitious women censor themselves and almost palpably reduce themselves; or if one does not, she is disliked in a special, generalized way, as much by other women as by men. She is not simply “an” obnoxious woman or “a" flawed leader, she is the expression of the flaws of female authority, which, the mainstream response seems to suggest, easily overflows the banks of natural female goodness. The Hillary Rodham of 1970s American feminism had to become Hillary Rodham Clinton to claim, and inevitably self-constrain, herself even while seeking greater authority. Over the years, with input from anthropology, literature, frequent arguments, and my personal experience, I’ve come to believe that the difference in comfort with female authority and leadership comes down mainly to three things: first, female leaders in very hierarchical (caste/class) societies benefit from belonging to a traditionally privileged category; secondly, where education is accessible only to a very small proportion of the population, educated women gain inordinate status and authority simply from education; and finally the symbolic imaging of women, usually religious, hugely constrains, or amplifies, how women’s power can be imagined. Here I am focusing on the last. As a Bengali, I grew up with Kali and Durga – manifestations of Shakti, power itself. The image of a woman, as woman, fully a woman, fighting for right was something I saw everyday in my mother’s puja room and celebrated every year at Durga Puja. Bengal, perhaps, has power associated with goddess more than any other part of India, but the idea of female Shakti is commonplace in Hinduism throughout the subcontinent, in some places further amplified by animist honoring of female power to generate and protect, in many places influencing the non-Hindu religions of fellow Indians. In the majority Christian U.S., on the other hand, there is no powerful female figure in Protestant iconography and the powerful Catholic figure of the Virgin Mary is above all modest and obedient, attributes that correlate well with the Protestant ideal of a good woman. Growing up in India, the Virgin Mary had been one more powerful female figure among many, not only because I learned about her powerful influence with her son from the nuns who taught me, but these nuns themselves, far from the male centers of Catholic power, both symbolic and real, and surrounded by a hospitable but uninterested majority of non-Christians, were erudite and independent. In the way one absorbs assumptions without really thinking about them, I assumed that their erudition and independence was because they were powerful women of Christianity. Only after coming to the US did I grow to sense and learn that, in this majority Christian country, women are not associated with power. At their best, they are good. So this Maha Ashtami, as I waited to watch the debate, both outraged and wickedly amused by Trump’s “locker-room” hot mic, and as I rooted for the candidate who might be the first female President of the United States, I wondered again at these paradoxes, and the competition between powerful and good. In the end, the best leaders are both powerful and good. They, whether women or men, are usually not perfect with either attribute, but we who follow, or are governed, are doing well if they get most of it right. In this period of increasing attention to walls, national boundaries, and trade protections, even as we experience climate-change-without-borders, are wirelessly entangled within an internet-(mostly)-without-borders, and watch global-access-flyers – grumbling far above slow-travel-migrants – move faster through every line in an airport, Gabriela Montero’s Ex Patria and Do Ho Suh’s obsessive recursions of “Home” extemporize on old-fashioned nostalgia, while Harrison’s “[Nest]” traces the delicate immediacy of a home qua home. Montero lives in exile in the United States and Do Ho Suh creates art – drawings, netted forms, and simulacra – all over the world while scattering residence across Seoul, New York, and London. Harrison was born in Germany, grew up mostly in New Hampshire, and lives in Maryland. Montero, a political exile, wrote, and plays, Ex Patria in the tradition of the Russian composers of the first decades of the twentieth century, fiercely longing for a beauty that was a promise of youth. The piece, dedicated to the people of her native Venezuela and a memorial for the 19336 people who were murdered in that country in 2011, conjures the memory of an “old country” that is wounded, potentially mortally. Over the four years or so since Ex Patria was first played, Montero’s implacable rejection of the current Venezuelan regime, including its extraordinary musical program, Sistema, for over 500,000 youth, has amplified the piece’s political narrative. Starkly, Montero’s critique of Sistema as a fig-leaf for a criminally dysfunctional government calls for letting the bubble of music pop, so to speak, to say “NO,” to wipe the body politic clean, and start anew. Ex Patria expresses the tragedy of the bubble, Sistema’s success and beauty growing in a fundamentally toxic and violent society, and its inevitable corruption.* Suh is not an exile like Montero. His existential mobility is unmotivated, like the life-cycle mobility of a firefly. He explains, “Once my fortune teller told me that I have five horses and that means that I travel a lot….” Embodying a form of mobility that is shaped by the technologies that are laid into our time, his nostalgia is for the form of home: the skeletal underframes, the permeable walls, the obtrusive shapes of haunting exits and entrances, including doors, windows, electrical outlets, and air conditioners. He is, perhaps, best known for his gossamer recreations of his apartment homes, but the most nostalgic piece, the most riveting for me, in the exhibition that is currently on at the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, is the piece that combines a miniature version of his traditional home in South Korea (placed on a truck) with a film that traces (or affects to trace?) the journey of the home to Madison Square Park in New York City. Suh seeks to carry “home” like a snail, a virtual snail with a virtual home, mind games, in which all of “home” resides in him, or he is always home. The exhibition in San Diego is presented across four spaces. Along with my local artist friend, Patti Fox, I walked through the two gallery spaces of the Museum, which are next to San Diego’s main train station and the downtown trolley hub, respectively, and separated by a wide road. We started at two o’clock in the afternoon, so the sun was very high and bounded the interior spaces so intensely that I couldn’t avoid attention to the very specific concatenations of radiant light, shadow, translucence, darkness, and projected light as we walked through one exhibition space to another. Suh, to my delight, is obsessively specific. His drawings have fine, straight lines, repeated one after the other until the image is complete. He sticks thread on paper to create figures and stories in which each loose end is perfect. His rubbings of every apartment wall, outlet, plaster pimple, and stovetop draw the viewer into mimicked attention to the banal phenomena of “home.” And his fabric simulacrum of his New York city apartment has astonishingly detailed embroidery and seams.** If Leslie Harrison’s “[Nest]” has nostalgia, it is very brief. The poem captures the fragile uncertainty of time, space, and fluttering materials that a nest represents. At some point, the elegiac home country of Montero’s Ex Patria and the obsessive scurrying of Suh’s “Home” recreations had their origins in wavering, delicate, and fundamentally physical moments like “this lodge that takes the shape of a wasp’s nest paper and swaying.” While Ex Patria bellows the loves and deaths of the multitudes that contain home, and Suh weaves them into nets that look repetitive and forever and then you notice that the figures vary and the nets cross continents, [Nest] whispers “the people on shore wave small scraps of fabric they’re white in the dusk.” Reading Harrison’s poem, with “heart” close to its geometric and literary center (“the heart goes dark the heart becomes just one more vessel waiting”), alongside Montero’s brief concerto and Suh’s art, I glimpse and want to capture how the three together represent the immediacy, mobility, and nostalgia of “home” in the 21st century, but I’m defeated by the over-determined neatness of my synthesis. And so I will stop here. *A contrary view of Sistema, held for example by Gustavo Dudamel, sees it as a hopeful program, preparing youth to be better citizens, morally and otherwise, who eventually will build a more beautiful tomorrow. **In my home city, San Diego, Suh has created a “Fallen Star,” a tilted house perched on the edge of a tall building for engineers. It has a lovely garden in front and pretty furnishings inside, and provokes an impossible imbalance when you enter it. When you leave it though: from the outside, from far away, it becomes a metaphor, an empty signifier, a wish. Thomas Hirschhorn A Ruin Is A Ruin Galerie Susanna Kulli, Zurich, Switzerland January 27, 2016 – March 31, 2016 A few weeks ago, in the middle of February of 2016, on my day off work in Zurich, I went to the Galerie Susanna Kulli to look at Thomas Hirschhorn’s collages on A Ruin Is A Ruin. I walked from the Hauptbahnhof, the main station, down a “military” road and past ordinary, tired buildings. A few steps led into a small gallery. Immediately before me was a large, undulating piece of cardboard, presenting a striking foundation of ruins from which an isolated ruin rose and gave way to a wasteland. A message in awkward orthography proclaimed what at first looked like: A RUIN ISA RUIN. Almost immediately I turned away from the large poster, putting my initial, peripheral view of more posters behind me, and turned to the collection of simulacra and writing under the glass of a small display case next to the entrance. In Hirschhorn’s terms, I turned from the art to the information. Hirschhorn is explicit about his aims in his writing and interviews. “Affirmation,” in the manner of Warhol, and “truth…that refers to nothing other than itself and asserts itself as a form.” His Ruins posters are layered, acquiring a three-dimensionality from both the vertical and lateral pasting of images, as well as from the building of the poster with a bottom and a top and an architecture that leverages height. Most of the posters have letters, usually words, usually including Ruin, in one case an overlapping RR, unavoidable persiflage of a monogram. The coda is provided on a small scrap of cardboard, in size a fraction of the large posters, on which is pasted the image of an indisputable ruin, accompanied by an honestly handwritten (uneven, with mistakes scratched out) text from Derrida: “… And then I would love to write, maybe with or following Benjamin, maybe against Benjamin, a short treatise on love of ruins. What else is there to love anyway? One cannot love a monument, a work of architecture, an institution as such, except through the experience, itself precarious, of its fragility: it hasn’t always been there, it is finite.” While the Derrida quotation and Hirschhorn’s Ruins collages both exclude people, connecting this exhibition to Hirschhorn’s earlier work on Ur-Collages (his collages presenting beautiful and ravaged bodies) leads me to suppose that love, loving people, also requires fragility, finitude. “A ruin is a form,” Hirschhorn says, and quotes Gramsci, “the content of art is art itself.” In a very ordinary way, I would propose that the content of art is also what it is not, what it excludes. In that sense, Hirschhorn’s A Ruin Is A Ruin exhibition both excludes information and surrounds itself with Hirschhorn’s own words, the Derridean coda, and layers of ancestral rubrics. So each poster is a form, “a truth… that refers to nothing other than itself,” and my delight with his work arises from the question: what is it not? The question what (each poster; the exhibition as a whole) is not implies a relationship to what it is not. In my encounter with the exhibition in Zurich, I found myself noticing four relationships: to information; to discursive and disciplinary context; to physical/spatial context; and to the agency of the viewer. I have written above about the relationship to information: both its deliberate exclusion, and its being hugged close via the coda and rubrics with long genealogies. This relationship to information merges with the relationship of the art to discursive and disciplinary context. In his interview with Sebastian Egenhofer on the occasion of his 2009 exhibition of Ur-Collages at the Galerie Kulli, Hirschhorn plausibly rejects (his own) consideration of “the public sphere of the art scene,” and, most understandably, even trivially, sees his work in relationship to that of Piet Mondrian, Andy Warhol, Martha Rosler, Caravaggio – a few of the artists explicitly named. His A Ruin Is A Ruin, interpellated by a Derridean coda, is also fundamentally present through its distinction from and location relative to other works (and subjects) in “the public sphere of the art scene.” Walking away, the relationship of the exhibition to physical/spatial context becomes evident, as I observe the slow dissolution of the urban landscape from the reserved, classically bourgeois buildings around the gallery to browning sidewalks that took me to a tunnel that stepped me through staccato colors out into an area of subsidized housing where I found walls with rounded, nature-sci-fi murals, Journey through the Jungle, all of this far from, and related to, the beautiful Altstadt and the heartbreakingly lovely contradictions of the Chagall windows in Our Lady’s Church. Hirschhorn’s ruins were there, then, in the middle of that geography with its particulate, too-big-for-one-telling histories. The collages in A Ruin Is A Ruin have a seductive beauty. Only one contains an obtrusive human (dis)figure, and that highly stylized. But this exhibition’s antecedent in the same gallery, Hirschhorn’s Ur-Collages, contained works that each displayed images of glossily beautiful humans and ravaged bodies – dismembered, flesh, entrails, blood. The gallery assistant, Anna Vetsch, who will one day run a gallery or museum of contemporary art, showed me photographs of that exhibition and warned me that they would be hard to look at. Remarkably, the images of that earlier exhibition did clarify my attention to the current Ruins exhibition, and, yes, the images were difficult to look at. I did not want to look at the disfigured human bodies; and I was not interested in the fashion photographs to which they were attached. I was curious about the compositions, but didn’t want to look at them. And then I read Egenhofer’s interview of Hirschhorn in which Hirschhorn says: “I am astonished time and again when viewers say, ‘I can’t see that,’ or even worse, ‘I don’t have to see that’ or ‘I don’t want to see that.’ That is an incredible thing to say, that is an exclusion of the other, and it is pure egotism when someone claims that he has the option of not seeing. Of not seeing the world as it is. That is an incredibly luxurious thing to do, a self-segregation, a turning away from the world that I will never understand.” So when Hirschhorn challenges the agency and choices of the viewer with his Ur-Collages, we can only suppose that, with his Ruins collages, he is also challenging the agency and choices of the viewer. His works ask – When you turn away from the Ur-Collages what do you look at? When you look at the Ruins collages, what are you turning away from? Contrary to Hirschhorn’s apparent intention, the truth of his work is not simply in the art itself. Perhaps there was only one moment of that truth when I viewed the exhibition, the moment when I walked in and glanced at the first poster before turning to the information encased in the glass. Perhaps there was a moment of truth for each work, a truth that became available in a brief liminal pause, during which the image hung separate, preceded and followed by inevitable captivity to context and information. The longer truth is that Hirschhorn’s work caught my attention, led to this writing, and will “hold up” because it must be seen within its larger contexts, which are specific and granular around this art, today, but schematized by the form of the work in ways that make contexts of other times and places relevant and questioned. A note about the photographs: All the photographs are taken by me with my iPhone. The photo showing some of the works in the Ur-collage exhibition is of a page in the booklet containing Sebastian Egenhofer’s interview of Thomas Hirschhorn. The booklet is available for 18 euros at the Galerie Susanna Kulli, which organized the interview and has published the booklet (bi-lingual in German and English). The last photo shows a keepsake collage that I created on a photocopy of the review of the exhibition in a Zurich newspaper.

A few days ago I watched Deadpool. I hadn’t heard of it until my spouse and daughter told me it is the hot, new cult movie.

So here is a quick review. Wry, clever opening credits. Some very good, funny lines. I knew and liked most of the music. And, in general, this is a very well-made, contemporary, white-bro fantasy, racist and sexist despite its sometimes successful attempts at irony. A dream movie for someone who wants to achieve (white) bro-hood through a mass-killing (with a not-so-background fantasy of a beautiful woman who loves you despite your ugliness, and is delighted by your big dick). But I’m writing this review because the movie provoked questions and connections that go well beyond its cool+fantasy appeal, not just to spout my middle-aged feminist judgment. Deadpool is very successful. I gather that many young people, including young women, think this is the best movie they have ever seen. I’m not sure what the young women love about it; my ability to empathize in this context is very, very limited. There is a cool teenage girl, perhaps the coolest character in the movie, but with very limited play. There is also one very tough (white) woman fighter, who in the end is defeated. I didn’t quite understand the plot purpose of an elderly, blind, African-American woman. In the scenes that included her, there were fleeting moments of intimacy and affection, but those moments had little other support in the movie. I very faintly sensed that her role had something to do with pushing the envelope on ironic offensiveness – what could be more aggressively non-PC, and therefore potently ironic, than making an elderly, blind African-American woman the butt of bro jokes? But the jokes in relation to her fell flat, so all that I ended up with was culturally foundational racism, sexism, and age-ism. In these scenes and in general, Deadpool seemed to me an expression of the U.S. zeitgeist, related to, and amplified in, Trump’s successes. My spouse and primary review partner pointed out that the culturally foundational elements of sexism, racism, and age-ism are just that, common to many, if not most, Hollywood productions, and told me that calling them out does not make for interesting commentary because they are to be expected. He pointed out that the success of Deadpool doesn’t come from these elements (though he would probably agree that the kind of success it has achieved would be hard to get without these elements) but rather derives from its layered persiflage of many years of self-important, taking-themselves-too-seriously, overly-earnest super-hero movies. From his perspective, this is what delights audiences who have been fed these movies regularly over the last decade or so. Certainly, Deadpool is substantially more sophisticated in ironic humor and self-reflexivity than the one Fantastic Four movie I’ve seen, and one of the best jokes in Deadpool is about X-Men. I’ve not seen many other movies in this genre so I can’t make a deep comparison. But while I might agree with his point about this reason for Deadpool’s success, I don’t think the foundational racism, sexism, and age-ism, that provide the warp for the movie’s weaving of its contemporary white-bro fantasy, are simply old news. In Deadpool, this foundation is refreshed as the movie connects to, expresses, and is viewed in the context of, a contemporary, mostly-bro, fantasy of recovering American (individualist) greatness, a fantasy that finds its most loud, caricatured, and white version in Trump’s speeches, but which also has more romantic versions that are more widely available, not just for white people and not just for boys and men. The romantic version in Deadpool allows any of us to long for one of the two fantastic social roles it celebrates – the heroic, bro-ish role of someone who survives and succeeds despite a hard life and ugly edges (and who ends up whupping the bad guy); and the immortalized object of the hero’s desire, who is, by the very nature of the role, someone attractive, loyal, and monolithically, uncomplicatedly loving (no doubts, no uncertainty, no resentments, not much discernible subjectivity; dirty socks are just dirty socks outside, waiting to be washed, there are no durable and mutating dirty socks of and in the heart and soul of the beloved). Deadpool rattles through its romantic version of quest for and achievement of individualist greatness, occasionally, very occasionally, with a titillating tenderness, and, beyond the effectiveness of its persiflage, the movie’s success also lies in pulling viewers into glossing some core part of themselves into one (or perhaps both, in some alternating format) of these roles. The Quartz article, “A tip to Americans from an Italian who saw Berlusconi get elected again and again and again,” is not about Deadpool, but it compares Trump and Berlusconi in a way that casts a darkroom’s red light on the U.S. zeitgeist that Deadpool refracts into (more) successful entertainment. I came to the US in late August 1980. In early September, my pocket was picked while I waited for a bus in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I was distressed for all the obvious reasons, and even more so because I was in the US and I’d never had my pocket picked in India! Most of the people around me looked uninterestedly sympathetic. Someone suggested I call the police. When the police came, they were large men, one light-skinned and one dark-skinned. One of them, I don’t remember which, asked me if I had caught sight of the pickpocket. I said I thought it was a tall man who had been right behind me in the throng, who walked away in the moments before I noticed my wallet was gone. The policeman asked, “What color was he?” I gaped at him, thinking green and blue. He looked at me. This was a college town. I was clearly a foreign student, fresh off the boat. “Black or white?” he asked.

That was my first direct encounter with the peculiar taxonomy of colored people – white or black – in the United States. Others, at least in the very late 20th century and early 21st century, don’t have color: they are either Native Americans or immigrants with some ethnic identity. I knew the term “Red Indians” from movies and novels, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard a real person use that color designation about another person; nor have I ever directly heard a person described as a “yellow”(-colored) man or woman. In the early weeks of that fall, I sat at the dining hall table that had only dark-skinned young women around it, several of whom were lighter than me; and I discovered that I couldn’t affiliate simply because they and I shared the same color range. FOB and young that I was, I didn’t understand that color was the superficial indicator for a much more deeply alienating taxonomy. After 35 years in this country, and now American myself, I am still learning. Today I, fuzzily and somewhat fearfully (because every word on color in the US is potentially hurtful), see “white or black” as the division between a category of people who have held the standard for voice and authority in the US, whether used poetically, violently, patronizingly, or just nicely, and another category of people who have struggled for authority, whether over their lives, relationships, or words.* This is not about individuals, whether black or white, who may struggle more, or less, depending to a very significant degree on their class background and access to the educational resources and habits of the upper classes. This is about a pernicious typology that makes the experience of one profoundly different from the experience of the other, such that the same words spoken by one and the other have cultural and emotional referents that are different. I was stimulated to write this post by a chance thought: what if Macklemore, with his White Privilege II, and Morgan Parker, with her poem “If You Are Over Staying Woke” were to chat. I’d hazard that no other white American could listen more carefully than Macklemore, and, yet, I would speculate that some core of Morgan Parker would not feel heard. I would guess that Parker would appreciate Macklemore’s honest speaking out as a powerful ally, and I wonder if she would hear patronage, regardless of his self-conscious intention to avoid being patronizing. As I write this, I’m deciding that just leaving the song and the poem side by side may be more effective than a direct conversation. Placing them side by side allows more space around each as well as space between, in which meaning can be heard, said, felt, witnessed, and created without being narrowed by the potential politenesses and pedantry of a conversation. These thoughts are at the surface of a messy confusion in my mind, the mind of a minority brown woman in the US who lived her formative years as a class-privileged member of the majority community in India, and therefore, to a significant degree, has a majoritarian mindset (i.e. oblivious to its own fundamental assumption of standard). I find myself both assimilating to the majoritarian mindset of white America, and spitting it out as I find it resonating with current and deep histories of injustice and cruelty. It’s easy for me to spit it out because I am a brown woman, I’m not white. But am I simply using my brownness as an alibi, pretending my majoritarian equanimity is brown Indian equanimity? Of course, there are surely instances when the majoritarian mindset of white America spits me out, but my own majoritarian mindset, along with class privilege, allows me to be oblivious. These thoughts, questions, my confusion, have increased in recent years as #blacklivesmatter raps insistently on my eyes and ears for attention; as I’ve developed deeper friendships with African-Americans; and as I’ve found and read more African-American writing. So where is my increased awareness, which is the other side of my confusion, taking me? In general, to curiosity, to dialogue, to protests, to expressions of solidarity, to Twitter and FB activism, to voting choices. In this blog post, it takes me to revealing my naiveté and confusion. I’m still learning. I care, and learning is one way to make that caring count. * As African-Americans have struggled for authority and voice, they have suffered violation and loss, but they have also produced great beauty (writing, art, music, performance) and extraordinary moral leadership, not just for Americans, but for all humans. Recently, between a daughter burbling about the chemical transferability of learning and a character (in my new novel) pushing the boundaries of artificial intelligence, I’ve been thinking a lot about learning.

As a layperson, I’ve thought of learning mainly in terms of younger learning – generational transfer of social convention and disciplinary knowledge, which, in environments that adequately balance boundaries and freedom, and nourishment and stress, develop capacity for higher-order connections, analogy, abstraction, and “extra-order” creativity – and adult learning which uses and further develops the higher-order capacities. All of this presumes that learning is a humanistic and social process. Of course, our physiology allows this learning, but, until recently, I didn’t seriously consider the possibility that learning might be, fundamentally, a physiological and/or logical process. Today, however, with explorations of the chemical transferability of learning, increasing understanding of the structure and activity of the brain, and the development of sophisticated algorithms for pattern recognition and unsupervised learning by machines, I, along with many others, am fascinated by, and curious about, the chemical and mechanical nature of learning. Snap! Palpably, truly, my brain shut a mental trap around the word “curiosity.” Aha. Where would curiosity figure in the chemical transfer of learning? Can artificially intelligent curiosity match human curiosity? What is the relationship of curiosity to learning and intelligence? So far explorations of the chemical transfer of learning are restricted to conditioned learning, so the question of curiosity is very far from arising. But I think we can ask about curiosity in machine learning. Curiosity in mammals includes both instrumental, problem-solving, motivated curiosity and (pleasurably) idle curiosity. Both kinds can lead to learning. The first sounds amenable to algorithmic machine learning. The second, pleasurably idle curiosity, sounds fundamentally inconsistent with algorithmic processes, but certainly one could code a machine to simulate idle curiosity. One could have an “idle” curiosity algorithm, with a cosmetic repertoire of pleasure indicators, linked to a mechanical random number generator, and one could code for recording and learning from the effects of the random, if not truly idle, curiosity. I think it could look pretty good and the machine might even derive quantitatively and qualitatively better learning than I do from my idle curiosity. So where would that leave me? At the limit, the machine cannot have idle curiosity. That does leave me (and you) with a fertile question: what then can the machine never have in terms of learning? (I think one could have a strongly analogous line of inquiry about self-consciousness. Perhaps in a future post. Or in a guest post?) Note: In this note, I use “learning” and “intelligence” to denote mainly mental activity (descriptive, analytical, creative, etc.). I am not looking in any primary way at “muscle memory,” emotional intelligence, etc., though, clearly, all of these greatly affect any person’s overall capacity and process of learning and “intelligence.” I also do not look at a crucial form of curiosity among mammals in general, but, most strikingly, among humans – relational curiosity. Related content: a fascinating article on gender and AI/Robots. In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty tries to find an economic driver of structural inequality that might be amenable to policy control; he finds that capital income contributes strikingly to increasing inequality and that, potentially though not easily, its effects can be reduced by tax policy. Most discussions of his book focus on his academic work of data gathering, analysis, and theory-building.

A second intention gets less attention. This is the intention to engage directly in public discourse: not simply informing public discourse, nor simply a written form of public speaking, but seeing himself and his work as direct participants in a marketplace that includes ordinary, not-scholarly, not-official people and, presumably, their language and ideas. “Social scientists, like all intellectuals and all citizens, ought to participate in public debate…. It is illusory, I believe, to think that the scholar and the citizen live in separate moral universes, the former concerned with means and the latter with ends.” For me, the charm and importance of his work, well beyond the competence of his (and his team’s) data-gathering, analysis, and theory-building, derives from this engagement, unabashedly personal, with a systemic moral universe that includes the scholar and the citizen. I started reading Piketty’s Capital around the same time that I read the transcript of Marilynne Robinson’s conversation with Barack Obama, and immediately promised myself that I would write this post, because Robinson and Obama’s conversation has the same quality of ranging outside the lines of conventional or official categories. In a back-and-forth that comfortably meanders from careful phrases to sentences that try to capture a truth so intensely they immediately reveal their own limits, then on to rambling words strung together thinking-out-loud, Robinson and Obama discuss the importance and meaning of Christianity in Robinson’s life and writing, the language and role of Christianity in contemporary politics, the gap between ordinary decency and mean-spirited politics, and race in the US, among other things. It’s not that such discussions are unusual or that the content is extraordinary; what is remarkable is the ease with which Robinson and Obama make the ordinary* commute with intellectual, author, President, in a public conversation. So, why am I writing this post? Because I was invigorated by Piketty’s, Robinson’s and Obama’s smudging beyond the boundaries of expertise and the lines of disciplinary language. I loved their engagement beyond the professionalization of their, and our, lives. In his book and in their conversation, these three people – Piketty, Robinson, and Obama – bring intellect into direct contact with ordinary life, in the public sphere. I hear their words bringing to the fore, in a wonderful way, an obvious but usually subdued understanding: that all people – social and political beings, whether “intellectual” or not – have equal stake in the moral universe that human society necessarily is. * here a noun Marilynne Robinson and Barack Obama chat on Sept 14, 2014 Part II of Robinson and Obama Chat |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed