|

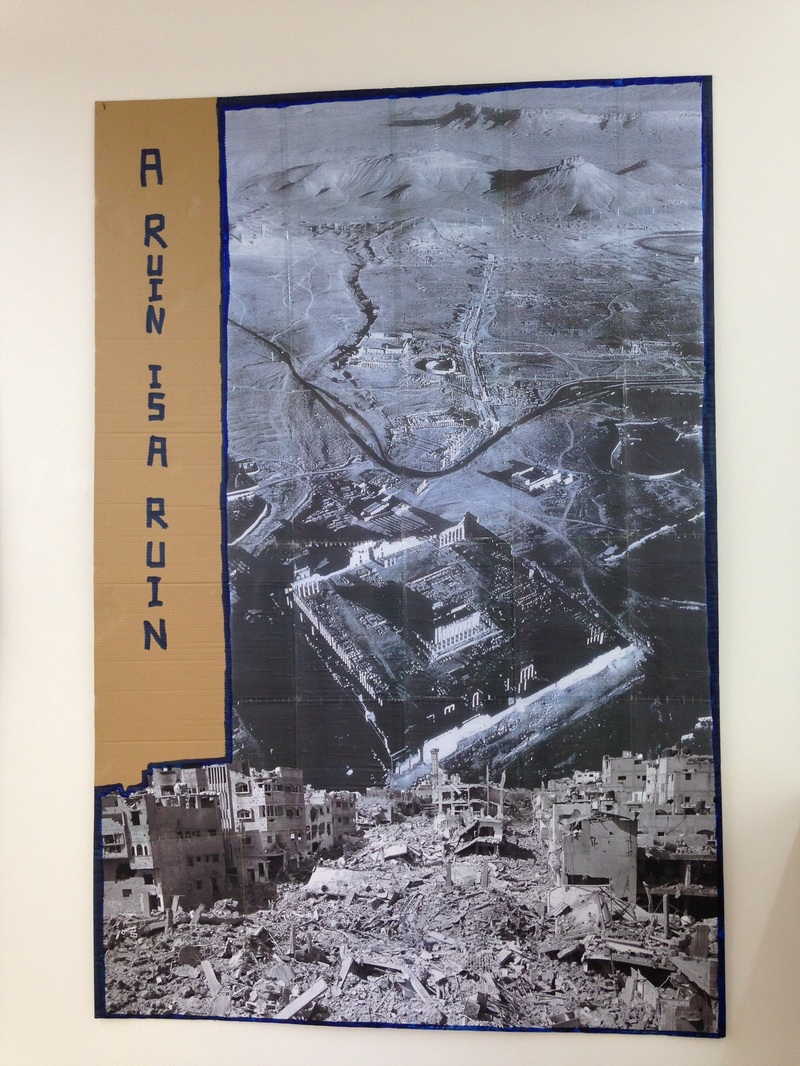

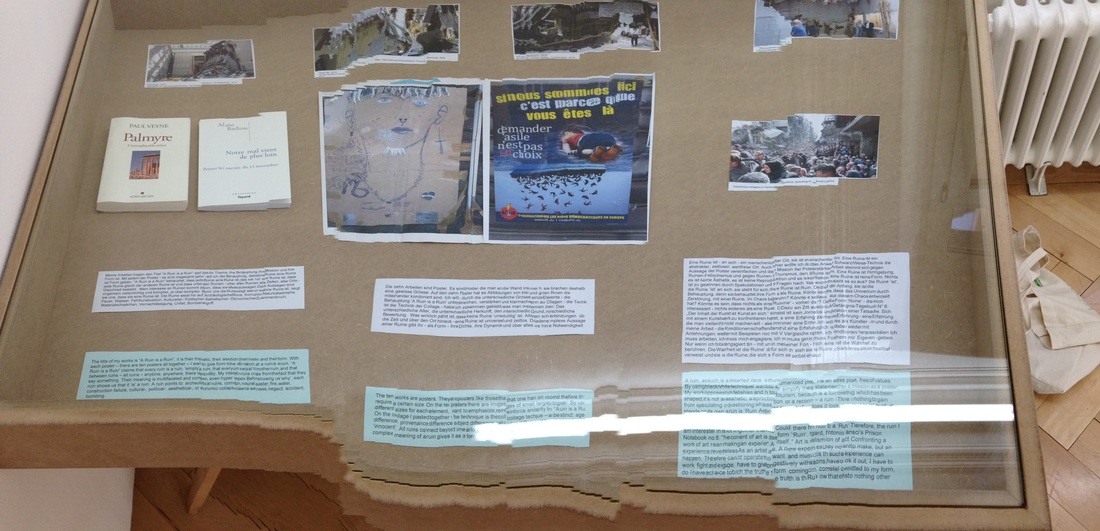

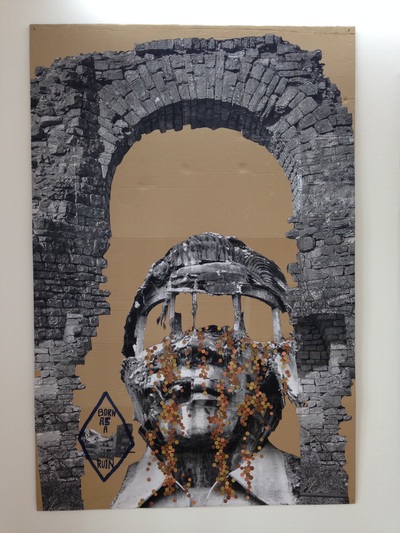

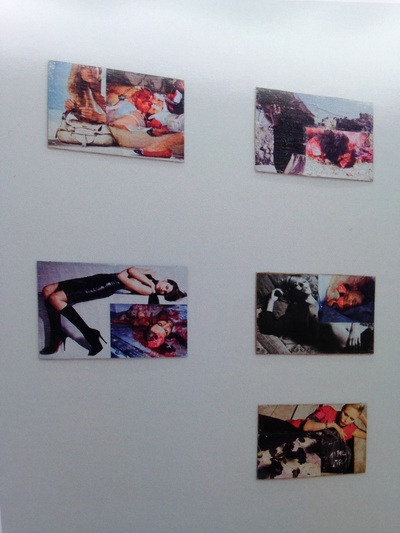

Thomas Hirschhorn A Ruin Is A Ruin Galerie Susanna Kulli, Zurich, Switzerland January 27, 2016 – March 31, 2016 A few weeks ago, in the middle of February of 2016, on my day off work in Zurich, I went to the Galerie Susanna Kulli to look at Thomas Hirschhorn’s collages on A Ruin Is A Ruin. I walked from the Hauptbahnhof, the main station, down a “military” road and past ordinary, tired buildings. A few steps led into a small gallery. Immediately before me was a large, undulating piece of cardboard, presenting a striking foundation of ruins from which an isolated ruin rose and gave way to a wasteland. A message in awkward orthography proclaimed what at first looked like: A RUIN ISA RUIN. Almost immediately I turned away from the large poster, putting my initial, peripheral view of more posters behind me, and turned to the collection of simulacra and writing under the glass of a small display case next to the entrance. In Hirschhorn’s terms, I turned from the art to the information. Hirschhorn is explicit about his aims in his writing and interviews. “Affirmation,” in the manner of Warhol, and “truth…that refers to nothing other than itself and asserts itself as a form.” His Ruins posters are layered, acquiring a three-dimensionality from both the vertical and lateral pasting of images, as well as from the building of the poster with a bottom and a top and an architecture that leverages height. Most of the posters have letters, usually words, usually including Ruin, in one case an overlapping RR, unavoidable persiflage of a monogram. The coda is provided on a small scrap of cardboard, in size a fraction of the large posters, on which is pasted the image of an indisputable ruin, accompanied by an honestly handwritten (uneven, with mistakes scratched out) text from Derrida: “… And then I would love to write, maybe with or following Benjamin, maybe against Benjamin, a short treatise on love of ruins. What else is there to love anyway? One cannot love a monument, a work of architecture, an institution as such, except through the experience, itself precarious, of its fragility: it hasn’t always been there, it is finite.” While the Derrida quotation and Hirschhorn’s Ruins collages both exclude people, connecting this exhibition to Hirschhorn’s earlier work on Ur-Collages (his collages presenting beautiful and ravaged bodies) leads me to suppose that love, loving people, also requires fragility, finitude. “A ruin is a form,” Hirschhorn says, and quotes Gramsci, “the content of art is art itself.” In a very ordinary way, I would propose that the content of art is also what it is not, what it excludes. In that sense, Hirschhorn’s A Ruin Is A Ruin exhibition both excludes information and surrounds itself with Hirschhorn’s own words, the Derridean coda, and layers of ancestral rubrics. So each poster is a form, “a truth… that refers to nothing other than itself,” and my delight with his work arises from the question: what is it not? The question what (each poster; the exhibition as a whole) is not implies a relationship to what it is not. In my encounter with the exhibition in Zurich, I found myself noticing four relationships: to information; to discursive and disciplinary context; to physical/spatial context; and to the agency of the viewer. I have written above about the relationship to information: both its deliberate exclusion, and its being hugged close via the coda and rubrics with long genealogies. This relationship to information merges with the relationship of the art to discursive and disciplinary context. In his interview with Sebastian Egenhofer on the occasion of his 2009 exhibition of Ur-Collages at the Galerie Kulli, Hirschhorn plausibly rejects (his own) consideration of “the public sphere of the art scene,” and, most understandably, even trivially, sees his work in relationship to that of Piet Mondrian, Andy Warhol, Martha Rosler, Caravaggio – a few of the artists explicitly named. His A Ruin Is A Ruin, interpellated by a Derridean coda, is also fundamentally present through its distinction from and location relative to other works (and subjects) in “the public sphere of the art scene.” Walking away, the relationship of the exhibition to physical/spatial context becomes evident, as I observe the slow dissolution of the urban landscape from the reserved, classically bourgeois buildings around the gallery to browning sidewalks that took me to a tunnel that stepped me through staccato colors out into an area of subsidized housing where I found walls with rounded, nature-sci-fi murals, Journey through the Jungle, all of this far from, and related to, the beautiful Altstadt and the heartbreakingly lovely contradictions of the Chagall windows in Our Lady’s Church. Hirschhorn’s ruins were there, then, in the middle of that geography with its particulate, too-big-for-one-telling histories. The collages in A Ruin Is A Ruin have a seductive beauty. Only one contains an obtrusive human (dis)figure, and that highly stylized. But this exhibition’s antecedent in the same gallery, Hirschhorn’s Ur-Collages, contained works that each displayed images of glossily beautiful humans and ravaged bodies – dismembered, flesh, entrails, blood. The gallery assistant, Anna Vetsch, who will one day run a gallery or museum of contemporary art, showed me photographs of that exhibition and warned me that they would be hard to look at. Remarkably, the images of that earlier exhibition did clarify my attention to the current Ruins exhibition, and, yes, the images were difficult to look at. I did not want to look at the disfigured human bodies; and I was not interested in the fashion photographs to which they were attached. I was curious about the compositions, but didn’t want to look at them. And then I read Egenhofer’s interview of Hirschhorn in which Hirschhorn says: “I am astonished time and again when viewers say, ‘I can’t see that,’ or even worse, ‘I don’t have to see that’ or ‘I don’t want to see that.’ That is an incredible thing to say, that is an exclusion of the other, and it is pure egotism when someone claims that he has the option of not seeing. Of not seeing the world as it is. That is an incredibly luxurious thing to do, a self-segregation, a turning away from the world that I will never understand.” So when Hirschhorn challenges the agency and choices of the viewer with his Ur-Collages, we can only suppose that, with his Ruins collages, he is also challenging the agency and choices of the viewer. His works ask – When you turn away from the Ur-Collages what do you look at? When you look at the Ruins collages, what are you turning away from? Contrary to Hirschhorn’s apparent intention, the truth of his work is not simply in the art itself. Perhaps there was only one moment of that truth when I viewed the exhibition, the moment when I walked in and glanced at the first poster before turning to the information encased in the glass. Perhaps there was a moment of truth for each work, a truth that became available in a brief liminal pause, during which the image hung separate, preceded and followed by inevitable captivity to context and information. The longer truth is that Hirschhorn’s work caught my attention, led to this writing, and will “hold up” because it must be seen within its larger contexts, which are specific and granular around this art, today, but schematized by the form of the work in ways that make contexts of other times and places relevant and questioned. A note about the photographs: All the photographs are taken by me with my iPhone. The photo showing some of the works in the Ur-collage exhibition is of a page in the booklet containing Sebastian Egenhofer’s interview of Thomas Hirschhorn. The booklet is available for 18 euros at the Galerie Susanna Kulli, which organized the interview and has published the booklet (bi-lingual in German and English). The last photo shows a keepsake collage that I created on a photocopy of the review of the exhibition in a Zurich newspaper.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed