|

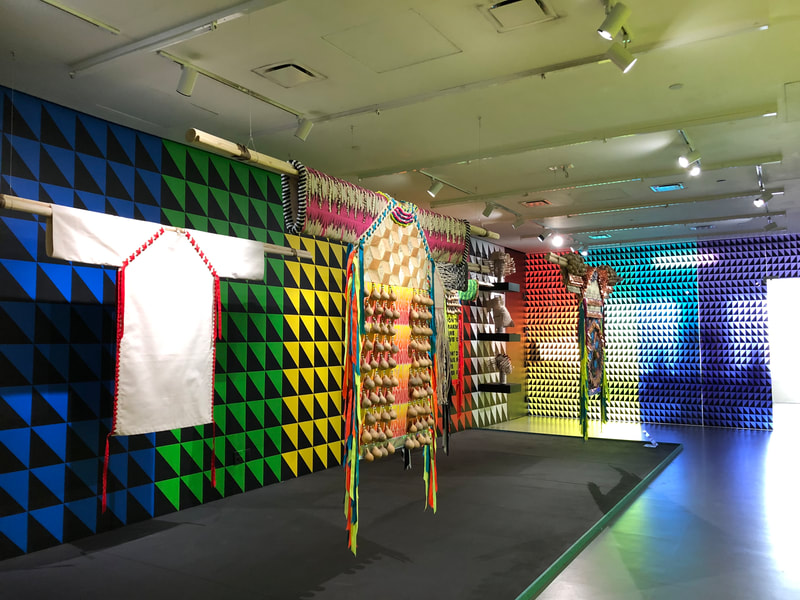

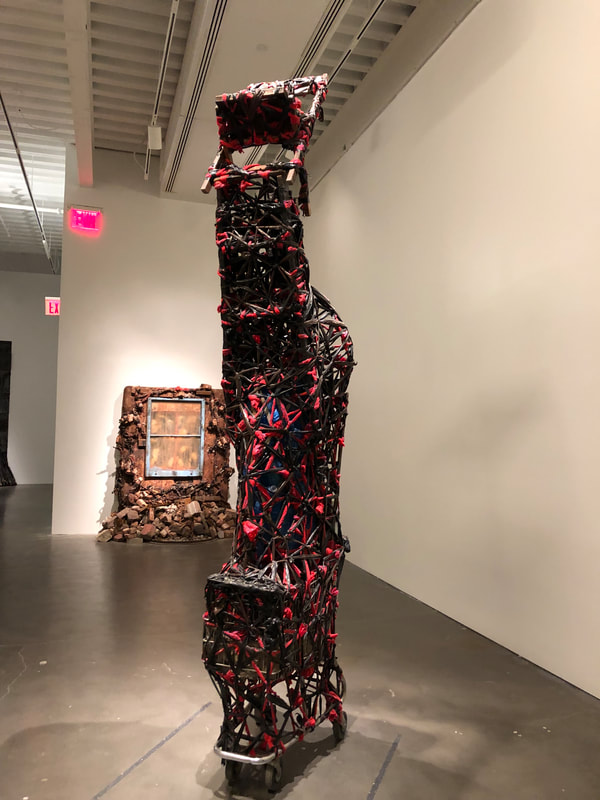

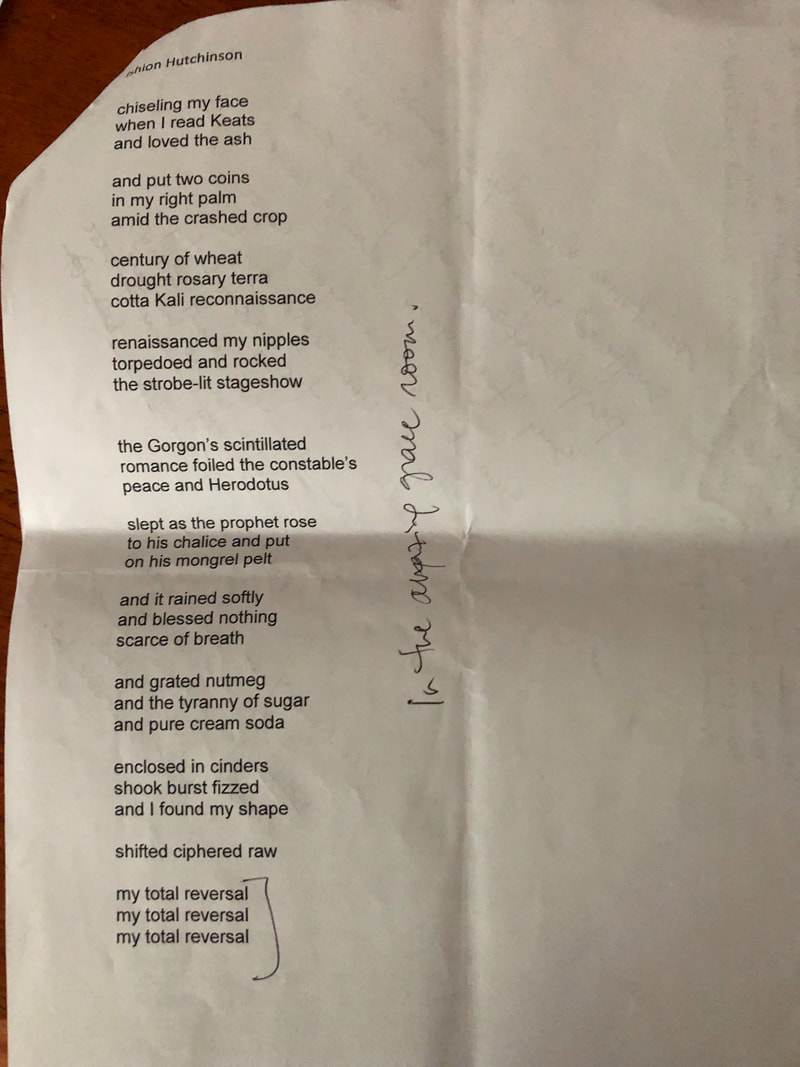

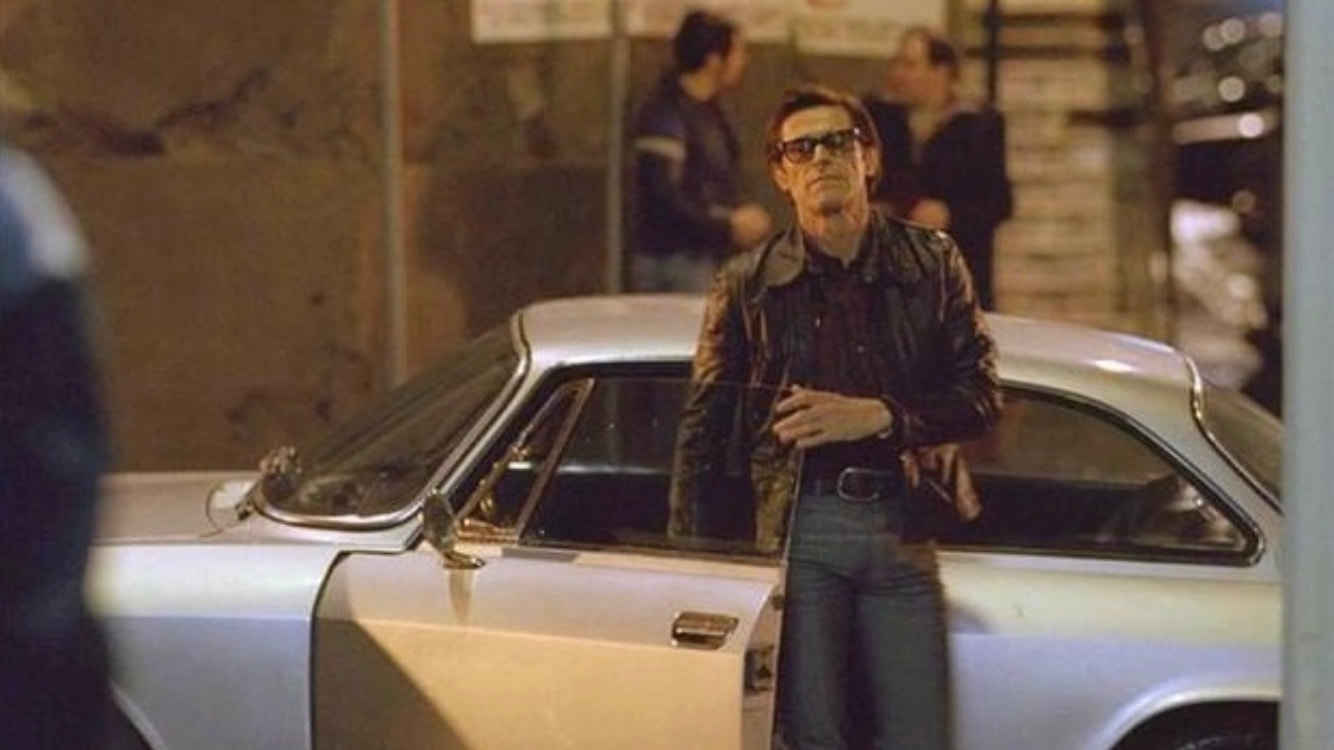

(Spoiler alert re the movie Pasolini) The sequence of Nari Ward, Ishion Hutchinson, and Pasolini just happened; there was no plan on my part. Nari Ward and Ishion Hutchinson were paired by the New Museum. Not unexpectedly, they were a good pair, or rather I found Hutchinson’s response to Ward’s art provided something like a blended glass, part mirror, part filter. More about that in a bit. I added Pasolini because I wanted to use my Metrograph membership; I could walk to The Metrograph from The New Museum, and Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini was playing at the right time for me to move in this way through the city. Interestingly, going to Pasolini also became the right movement for a kind of intellectual and emotional trajectory. Though this is often the case as we knit the past into some kind of coherence, in this case I struggled with making the sequence coherent, then forced a coherence, and then was struck by what came of and from the forced coherence. I went to The New Museum for the first time about two weeks ago because a friend wanted to go there and I’ve wanted to go there for a long time. We started on the top floor with Jeffrey Gibson’s kaleidoscopic work and I passed through his work, loving the color and the immanence of movement. Later, I passed through Hélène Cixous’ odd, insightful, and romantic essay on Gibson’s work. “A dislocation is at work,” she wrote. Then we went down three floors of Ward’s large installations and smaller, more compact, art in the exhibition called “We the People.” The making of art from found objects is not new but the poignancy of this exhibition lay in the bend between the mourning of pain and history, and the fertility and beauty of, somehow, life. I had not heard of Nari Ward before this and got a little uncomfortable when I heard that he is a Harlem-based artist and his art connects directly to dispossession, not only of the past, but directly in the effects of gentrification in the present. I moved into West Harlem in June 2018, an innocuous, older-ing, and brown woman. I belong here, and I don’t. I had noticed, when checking out the museum before I went there with my friend, that Ishion Hutchinson was going to do a gallery talk on Nari Ward’s work. When I asked if there were still tickets available for that gallery talk, I was told there were. I was stunned. I guess this is NYC. I said, if you don’t think they’ll sell out while we, my friend and I, go through the exhibitions, I’ll wait to see Nari Ward’s work before buying a ticket for Hutchinson’s gallery talk. They assured me there would still be places, and there were, and once we’d walked through and down all the floors, I bought a ticket for the talk. So, on Thursday, May 16, my hair freshly colored, I went back to The New Museum, and waited for Ishion Hutchinson’s gallery talk. Ishion Hutchinson, like Nari Ward, is Jamaican-diaspora African-American. He is a poet I much admire. He took us, a group of about fifteen people, through parts of “We the People,” with eloquence, diffidence, clarity, and kindness. He took us – none of us belonging to the African diaspora, though all of us share fraught histories with Nari Ward and him – through touching what ‘fugitive’ can mean in history, selfhood and art; through hearing the grandness of aspiration while living in “material fetishes of failed utopias;” through sensing, distantly – in our case, each of us, perhaps with some guilt, or shame, or desire – “an old resilience which is part of [Hutchinson’s] heritage.” He told us about the abeng, and made its sound with his breath, his throat, and his mouth – this was a generosity of sound, not just a performance or lecture – and related it to the artwork called Savior. The abeng, he told us, makes the sound of the fugitive. He lost his voice briefly after making that sound. He stood in front of the two pieces called Breathing Panel and, at the end of his prose response to the artwork, repeated, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe….” In that brightly-lit gallery, with chattering, whistling sounds from an adjoining artwork, with only one other African-American, a gallery attendant, in view, with one other gallery attendant who looked Latino, and me, a class- (and caste-) privileged South Asian-American, with everyone else phenotypically white, mostly women across a range of ages, I wondered who couldn’t breathe now, why couldn’t they breathe. Who is breathing? For how long? Then he took us to the large, dark room in which Amazing Grace was installed; “a womb, a slave ship, an ark,” he called it at the beginning and towards the end. He walked us, two-by-two and holding hands, through the stroller-ship-womb. He read his poem Sprawl and repeated “my total reversal” – the last three lines of the poem – more than three times. And then we were done. And I got him to sign my copy of House of Lords and Commons which he not just signed, but also inscribed with “a small, drifting raft” for me. I walked out into the sunny afternoon, exchanged cheery words with one of the outside guards, walked through Chinatown, got a text message from my daughters in which they laughed at my ‘culture-vulture’ day, got to The Metrograph, and bought a ticket to see Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini. On Instagram, I posted some pictures and wrote: it’s hard to call walking through Nari Ward’s work at The New Museum a pleasure, but perhaps one can call it a tenderness, an amazement at how beauty can come alongside, and from, ugliness and sorrow while underlying cruelty and pain remain cruelty and pain. Pasolini starts, if not right away then very early on, with explicit, aggressive, unlovely sodomizing of two submissive young women. With Pasolini, I seemed far from the fugitive grief and anger and grace of Ward’s work and Hutchinson’s words. There was abject or abjectify-ing sex, followed by ordinary domesticity and interesting, but cold, words. “Narrative art is dead,” Pasolini told us, “we are in mourning.” “Mine is not a tale, it is a parable,” he said, “I am a form, the knowledge of which is an illusion.” To Pasolini, it appears, I, Meenakshi, am a moralist, who neither seizes the right to scandalize nor feels pleasure from being scandalized. About a third through the movie, I wrote in my running notes: so far there is very little that one might call kindness, or love, or tenderness. I watched more sex -- this time apparently not abject or abjectifying, more a kind of revolutionary procreation in a reversal of desire -- between beautiful people, with a raucous audience within the film, and us, a quiet audience outside the film, with our own arousals and withdrawals. Pasolini sees his work as a revolution. “I’m asking you to look around,” he says, “and see the tragedy… … starting with universal education … which leads us to want … and not stop short of murder…. … an appalling tradition that is based on this idea of possessing and destroying.” * The tenderness came at the end of the movie, when Pasolini is beaten to death on an industrial beach and the movie closes with a “clip” from a made-up movie based on Pasolini’s last work-in-progress. In the clip, Epifanio, an older-ing man, and his young companion are trying to get to Paradise and Epifanio can’t go on, so the young man says, “The end doesn’t exist. So we just wait. Something will happen.” Obvious shades of Godot, but owned here in its own terms, with its own peculiar pathos. In the end, the tenderness comes from the unabashed living of, and looking at, life with all its ugliness, its earthiness, its longings, its sensuousness, its beauty of form and light and shadow, its flaws, and just life. In general, I prefer to look at, sense, and join joy and tenderness of a different kind, but I did feel the tenderness at the end of this movie. Then started the struggle of knitting the coherence of my past. In my head, I stared at the obvious challenges of colonialism, racialism, the cruelty and survival of color lines of history, simplistically pitted against normative sexualization, scandalous desire, the intense ambivalence – intimacy and violence – of sex, and the cruelty and survival of power lines of history and didn’t get far, actually didn’t get anywhere, so retreated to higher abstractions. This is what I found. In Pasolini, there is no redemption, no desire for redemption. There is (only?) a wild grasping for freedom outside a cruel system that must be broken. In Pasolini, to the degree there is redemption, redemption lies in the external viewing of a complex tale – not a parable – about an ambitious fragility, or a fragile ambition. In Ward’s work and in Hutchinson’s words, there is redemption. Pain is overcome – indeed redeemed – by creation, by making beauty and life, and, in flashes, love and joy, from the remains of things, bodies, words, feelings, life itself. In Ward’s and Hutchinson’s work, perpetrators are on the other side; Ward’s and Hutchinson’s focus is on fugitiveness and resilience (Hutchinson’s words). In Pasolini, there is nothing fugitive, no one hides (except, perhaps, one time in the movie when Pasolini evades his interviewer’s question about what would remain if Pasolini could magically wave away everything he opposes), apparently nothing is hidden, perpetration is right there in front of you, drawing you in, people are broken down, perpetration itself is broken down. From this forced coherence, I knitted an easy/uneasy synthesis. In the face of suffering, sometimes one wants to shove perpetration up front and say, “fuck you, I don’t care!” Other times, one holds on to beauty, to the possibility of beauty; you want to cry because you cannot but care. And, zooming out, a creation that expresses only one of these impulses will feel flat – just brutal, or just sentimental. I did not find Ward’s, Hutchinson’s, or Ferrara’s work flat. To close, in my way: when I first decided to write about my forced coherence, I didn’t plan to include Jeffrey Gibson’s art and Hélène Cixous’ writing. But, having written thus far, I want to end with Gibson’s resplendent art. That is also life. And Cixous wrote of his dolls, which did not figure in this current New Museum exhibition, “… these were his people, his heritage, his self-portraits. Beautiful dreams, realized, and guarding their secrets.”

*Note: I wrote these words in my running notes. I’m pretty certain all the words and the logic they convey are accurate, but I’m not so sure about the ellipses.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed