|

Anna Seghers’ Transit is astoundingly contemporary, though completed in 1942.* In the most practical, palpable ways, the book describes the pillar-to-post, paper-and-more-paper, and rules-petty-power/lessness-and-helplessness of trying to cross a national border when you are wretched. The novel was written in the middle of the 20th century, the nation-state-century, when the science of borders became so fine that it could define in OR out, pure OR impure, and even what morally belonged as opposed to what must be kept out, just by whether you filled in the correct forms correctly, which allowed the gatekeepers to see quickly the lines that ran on one side and on the other side of you. A primary line running right through you did not, does not, bode well.

I entered a mild form of that kind of transit world in the 1980s and early 1990s, as I went to and from the United States as an Indian citizen with a U.S. student visa. Today, as a U.S. citizen of some means, I rarely have to enter that world. In 2018, we still seem to be in a long nation-state-century, though perhaps we’re in a globalized-hyper-transit century. We won’t really know until the evolving science of borders catches up with contemporary phenomena, forms, and technologies. So that’s it for the most obvious point to be made. Transit, the novel, was wholly suited to being made a contemporary film, which it has been. But Transit is not just a novel that has contemporary resonance. It is a story that is both fascinatingly flat and intensely dynamic. It is as if Seghers cut a slice of a whorled, recurrent world – that she calls an “ancient, yet ever new … … present” – and conjures for us all the details – people, forms, places, ships, days, victuals – as they move, connect, break down, reconnect, slip off, and are replaced. The story is narrated by a young man, in my view with the voice of a mature woman (plausibly a mature man, but implausibly a young man). In that period, a woman could not easily have wandered, gazed, and desired, so the narrator is a young man who is a curiously passive and blank character. His main foil, a young woman, another blank character, is hyper-active and always running after. Third in the key triangle of the novel is the explicitly blank character – for all practical purposes a fantasy – of a dead man, a writer, whom the narrator pretends to be and whom the young woman seeks. The story of these three blank characters becomes the web that holds the world of transit in Marseilles at the beginning of World War II. Strung on this web – moving along, sometimes jumping off or jumping back on – are small characters, socially and otherwise varied, who are perfectly alive. Encircling the web are small, and larger, and overlapping, environments – cafés, waterfronts, stairs, rooms with a wall on this side and a wall on that side, a view of the sea beyond “where the road took a turn and the wind was the strongest” – which add up to what Marseilles was at that time, but also, as peopled by the various small characters, to the state of transit as the roiling object of the story. Anna Seghers draws us in with the seductive narrative threads of quest, adventure, impossible love; in a curious inversion of the Orpheus-Eurydice myth, Marie runs after death and finally meets it. At the end, these narrative threads remain thin – almost transparent, almost air – but sustain a busy world of “present,” with all its waiting, living, and small moments of kindness and loving amidst known meanness, desperation, and death. The basic triangle, the detailed representation of place, and the reliance on small, recurrent characters are not unusual.** What is striking about Seghers’ novel is the deftness with which she uses a somnambulistic, Heinrich Böll’s word, narrator to tell a compelling and dynamic story about a slice of time. * It was first published in English and Spanish translations in 1944 when Seghers was in Mexico, and appeared in German in 1948 when Seghers was settled back in East Germany. Seghers’ choice to live in East Germany was controversial. The permanent return of the authorial voice of this novel to East Germany does intrigue me, but maybe only because I have some deceptive clarity of hindsight and distance. ** Reliance in long fiction on a wide variety of small, recurrent characters seems to belong more to places and times where lives are crowded and not as socially segregated as they seem to be for the dominant literary writing classes of the United States.

0 Comments

Two weeks ago, a companion called Leah Goodwin taught me and others a mysterious healing process. Mysterious to me, that is, probably not mysterious to its practitioners, whether in Hawaii, its original home, or elsewhere. According to Leah’s teaching, a therapist heard that a healer cured a group of unhappy people, with bewildered minds, without using drugs or psychotherapy. The process has a name that sounds silly to me – ho’oponopono. The therapist, Dr. Ihaleakala Hew Len, tried it out, found it worked, and passed it on, as Leah did.

When Leah talked us through the process, I found myself sandwiched between tenderness and embarrassment. Used correctly, it calls for complete and ridiculous openness. Nobody could, or should, be open like that, not even a child, I thought. But when Leah taught this, I was with a group of people I’ve grown to love and trust. I stood in the shadow of friends who knew I was a fool and somehow found me wise. With them I could be that open, that ridiculous. Ho’oponopono involves the incantation, with conscious and deep intention, of four sentences to oneself, or to another, preferably both (and, if both, that means all). The sentences, Leah told us, could be in any order. She has a preferred order, but any order is fine, so long as all four sentences are understood, spoken, and intended. These sentences sounded moving and profound, even divine, among these friends I trusted and who learned this process with me. Imagined beyond this group, they seemed frightening. They risked giving away too much, I could lose myself. If they were not matched, I could be reduced to a sentimental puddle – abject, without definition – and forever depleted. So what, already, is this incantation?! What are these sentences? I’m sorry. Forgive me. Thank you. I love you. As I quickly typed these sentences, then hurry my eyes away from them to these words here, I think, gosh, if Kavanaugh said these. Of course, I don’t want him to, because that would make him pretty amazing – what were those words I used? moving and profound, even divine – though conservative. His saying these sentences would challenge us on the political left to take “compassionate conservatism” seriously, to consider saying these sentences to conservatives. But, ha, ha, he is far from saying it and, from where I sit, conservatism still looks rather un-compassionate. In case you (meaning I) need reminding, I still don’t like him and I still want to work for change in the 2018 mid-terms. Rationally, truly, ho’oponopono has its limits. Dragging the process beyond these limits can be dangerous. In some ways, best to forget all about it. But I shan’t, because ho’oponopono is not about reducing myself and you and susceptible varieties of bleeding hearts to loving blobs without definition, difference, and conflict. Ho’oponopono is not about side-stepping definition, difference, and conflict. Ho'oponopono is being unafraid to love even where there is definition, difference, and conflict. It is trusting that I will not lose myself if I say I am sorry. It is trusting that gratitude/love/apology/forgiveness and accountability can co-exist. Indeed, gratitude/love/apology/forgiveness offered with the (embarrassingly!!!) open spirit of ho’oponopono, is a true invitation to accountability, to own all of yourself. Where ho’oponopono is most needed is where it is hardest. I can’t yet use it in my hardest places. Better to laugh. Better to scorn Kavanaugh. Best (more sneaky, more virtuous) to ruminate: if I think Kavanaugh should say I’m sorry Forgive me Thank you I love you … what would it mean for me to say to Kavanaugh I’m sorry Forgive me Thank you I love you ? And yet, today, with all the swirling ill-will that continues to surround and emanate from the Kavanaugh nomination, even this virtuous self-examination, this sneaky hypothetical, is walled up and dull. Months ago, a friend was stricken by the finitude of life and fear of regrets. We talked about this urgent – galvanizing rather than paralyzing – fear of life ending. I couldn’t empathize because I have not feared death in a long time, if ever. I have feared disability, which could come with age but also unbidden from accident or disease; and, in particular, I have feared, immodestly, the dulling of my fine mind, but fear of death? No. We quickly and lightly attributed the difference to my Hindu, rather than Judeo-Christian, upbringing. I have often said that I don’t have to do everything in this life. This does not mean that I believe that I will live another life, just that more lives than this life of mine will be led. So rather than the end or regrets at the end being important, it is – most tritely – living right now, “this is what I want to do, this is who I am,” that has been important to me. This is a frame that has served me well, as I have genuinely enjoyed a little patch in a concrete path that looks like a woman dragging a sack behind her, and, less whimsically, was consumed, with awe, by a storm of jellyfish, thousands if not millions streaming past me, a few stinging my face. These are sensory joys. In each case, it was not just an image, or a sting, but, with the concrete it was the feel of the light, the humming of a high-voltage wire above, and in the water, again, it was the light, or lack thereof, the awareness of gristle – Silky Shark bait, in the water amidst the swarming points of light – that I could not smell. But the gentle joys of the moment are not only sensory. Words can snare me, not just their rhythm, though, admittedly, it’s their rhythm that typically lures me first. Ideas can make my eyes widen, my fingertips feel alive.

In this way, reading The Paris Review’s interview with Luisa Valenzuela, whom I met in Tepoztlan in January, and chose to adulate though I didn’t really know her work, or her, led to a gentle moment with “the badlands of language,” from whence, according to Luisa, women come. Reading that phrase, I wanted to own it, not possessively, but gently, like the jellyfish stings and flawed concrete. I, a writer, come from the badlands of language. What does that even mean, as one of my daughters would ask. It has something to do with anger, I think, something to do with the paradoxical freedom of someone who struggles, who fundamentally is not and can never be free. We cannot just be the flower that offers its beauty and perfume freely, indeed the flower does not do that either, but that is a tangent I will leave aside in this piece. Learning to gently enjoy the beauty of the moment is truly a source of peace and wonder, that – as I let the beauty of this moment, of writing this piece with morning light falling on pictures of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Ray Charles; falling also on a postcard of one of Do Ho Suh “houses;” and, above all of these, falling on my collage of Thomas Hirschhorn’s ruins in Zurich – relaxes my body. I rub my cheeks. The beauty rubs on to me. This is a benediction. But my life, coming from the badlands of language, in many ways quite literally, is not only benediction. Realizing this is not gentle joy. Indeed, it returns me to wildness, to wilderness. The Silkies never came, the gristle got caught in my hair. As I write this, the morning light is lovely, but cortisol, fear, and desire are in my fingers as well. Cortisol, fear, and desire are not gentle; they come from struggle. Struggle is wild. The flowers are not free. I have already written from that wildness (read my first novel!). How do I live with it? How do I hold it as preciously as the gentle joys of each moment? It calls for risk in living. Does risk in living mean risking loving (as my first novel explores)? When the end comes, there is no happy ending. There is just the limited end. Everything else goes on. Struggles and projects remain unfinished. I, with a happy Pollyanna-ish mind, want to end this piece with a call for, a touching of, a blowing out of the “joy of loving.” That phrase wrote itself into the title and I am loth to throw it out. But the joy of loving is what it is. You can only have it if you have it. And otherwise, or rather in any case, you struggle. Note on jellyfish photo: Our guide and underwater photographer did not photograph the swarm. These jellyfish, also lovely, also stinging, also amid the flesh and bone of the shark bait, came before the swarm. Epilogue: I’m going to dive again. My daughters have gone back to their adult lives. A period of reconnecting with them and friends over the winter holidays has closed. Most memorable were walking by the ocean and in the desert; eating and drinking – salad with fennel, chile con carne con butternut squash, lamb stew, chocolate-cherry-cayenne gelato, ramen, molcajete stew, candied ginger, yucky trail mix with chocolate chips, esoteric cocktails, superior Korean plum wine, water, and so much else; conversing with friends, from our neighborhood and far away, who came to our home, or invited us to theirs, or met us over some interesting food or drink, or chatted with us on the phone; holding on to family who called and skyped and said, once more, “we’re here, you’re part of us”; realizing and proclaiming that taking photographs just adds to the fullness of loving life and wonderfully – meaning full of wonder – having three new lenses with which to experiment (thank you, Milu!); and hearing new music, and dancing – gosh, listening to Yasmine Hamdan (La ba’den), Moses Sumney (Plastic), Rapsody (Knock on my door), Thundercat (Walk on by), Ibeyi (Deathless), and Kamasi Washington (Truth), in that order, and so much more, and then reggaeton ringing in my ears, moving inside me (thank you, Pia! … and Frank, for playing the reggaeton all the time…).

This period of reconnecting came at the end of an odd year, one that was marked by mind-numbingly dispiriting politics, deep existential challenges for me and several people close to me, and some fantastic new adventures (including, in starring roles, sea hares, osprey, bison, whale sharks, sea lions, and me as a skater) in stunning environments (including the highlands of Montana and Wyoming, the ocean around Baja California Sur, the desert east of San Diego, and the long paved promenade by the ocean that extends from the Pacific Beach pier to well beyond Belmont Park in San Diego) and restorative trips (visiting dear family in India, and dear friends and family on the East Coast). 2017 – odd, dispiriting, challenging, adventurous, restorative – is over! Renewed by the gifts of the holidays, my priorities for 2018 are all action — publish, write, make some money, engage in political action, and be fully myself while figuring out my life as an empty-nester. In a couple of days I will go to Under the Volcano (UTV), a writing workshop in Tepoztlan, Mexico, that focuses on global literary fiction, poetry, and nonfiction. I plan to use that time to ground an intention that is already alive – to be happily aggressive and ambitious in my writing life! This year I will publish my first novel, Night Heron, or move it substantially into a publishing pipeline. In theory, five editors (three in the U.S. and two in India) are reading my work. I will send more submissions this month and early next month. If I do not have a major breakthrough in mainstream publishing by the end of May this year, I will self-publish Night Heron, and draw on friends and colleagues all over the world to promote it. That means some of you! This year I am giving up bashfulness with regard to my writing. I am ready to move on to my second novel. I have already written about half of the first draft. I have ideas for a third and possibly a fourth novel. I know, confidently, that writing is not about writing one perfect novel. It is about writing the best first novel one can, and then moving to the best second novel, and so on. The first cannot be allowed to cannibalize the second, the third, the whisper of a fourth. When you will know me as a fully-fledged writer, if I live long enough and write fast enough, you will know me as a writer of several splendid novels, each the best for that period of my writing. After returning from Tepoztlan, I will work again, briefly, on new submissions of my first novel. Then I will turn to other things until May, only responding when asked for more, and editing when invited by someone with serious interest. I will keep writing my second novel, Pretty Lights. Stay posted. Amidst writing and pushing to publish, I will also return to political activity. The 2018 elections are coming. I will be contacting stalwarts who, throughout 2017, continued to work on building enthusiasm and commitment, which effectively has meant sharing knowledge and sustaining hope that change is possible. I will be active. I am writing this here so you can hold me accountable. Perhaps, even, you might join me and others in working to flip Congress or in some other way to build a social, political, and economic system that is deeply and genuinely more fair. The last thread of action is about being, which is active. Our children have grown. Our home has two older adults who “have their lives back.” Our time, our nights are our own again. Our meals are complex again (actually now they become even more complex when our children visit!). Our respective work no longer needs to be contained, nor is it a guilty escape. We’re two across the dinner table. The last time we were consistently two at the dinner table was about twenty-four years ago. We’re young old people now, or old young people. I’m a Fresh, Old Voice, after all. A lot of this is new to us. We’re adventurous, so new is good. We’re also yoked. We pulled together well when we carried the children; we still pull together well when we carry the children. But most of the time now we don’t need to carry the children. So our separate, respective unruliness is back, which makes the condition of being yoked really hard work. Being active this year, then, includes being fully myself while also paying attention to my partner and the mechanics and affect of that pesky yoke. Publish, write, make some money, engage in political action, and be fully myself, though yoked. WARNING: If you have not read the book, there are spoilers in this review.

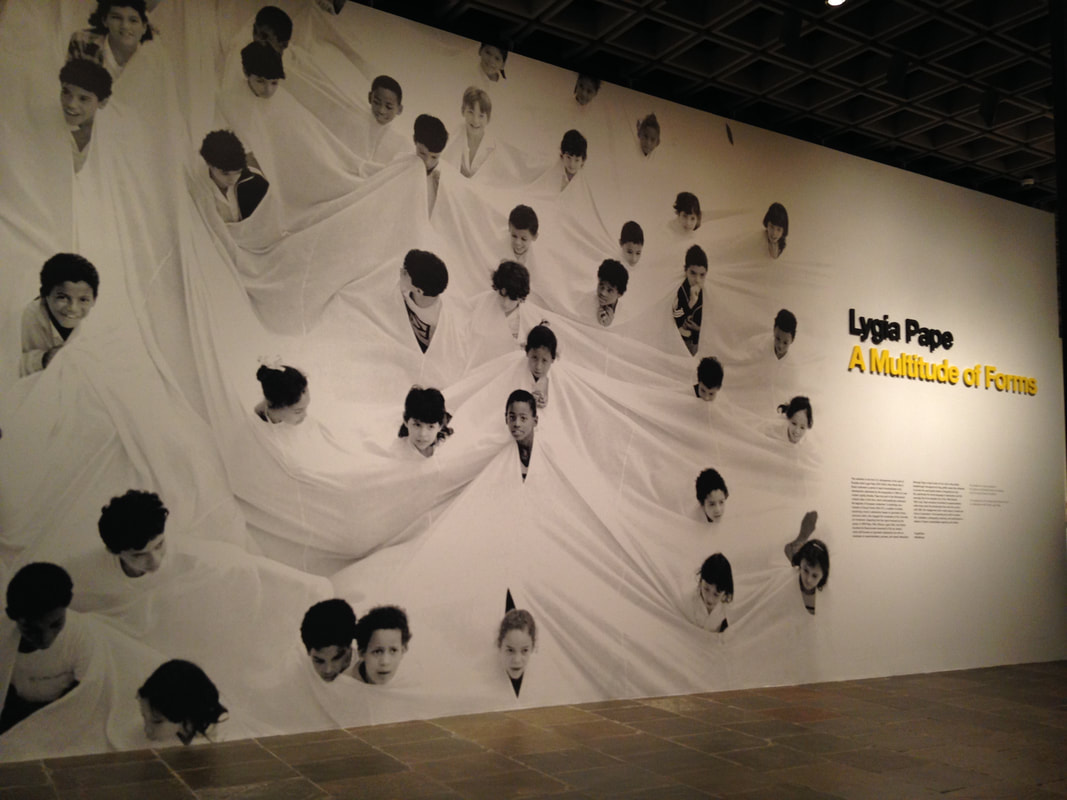

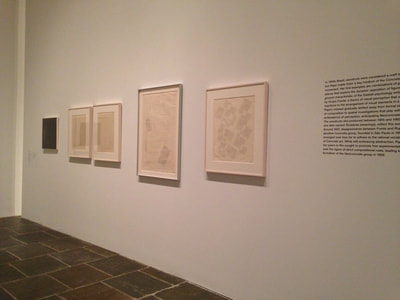

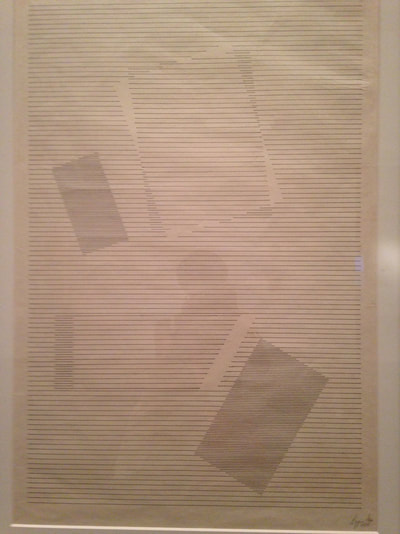

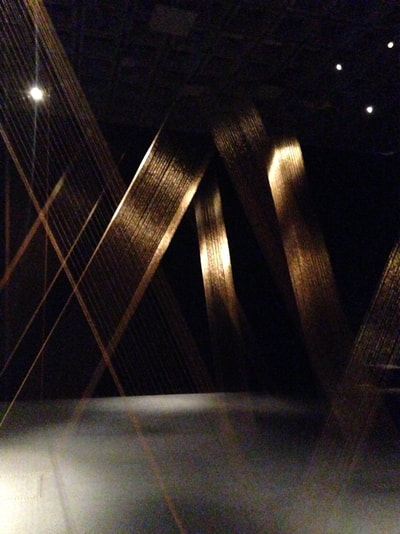

Like many cosmopolitan, post-colonial South Asians, Hari Kunzru writes extraordinarily well. He knows and loves words in the English language, not just the functional language of the British Islands, but the de-territorialized language of twentieth century globalism, kneaded by diaspora intelligentsia, whimsically dipping into the vernaculars and dialects of English-speaking localities, and – in Kunzru’s case – ironically, but also desperately-lovingly, seeking to use English, a language of modern power, as a moral language that mourns, assesses, and stays alive. In White Tears, he writes beautifully and he has a fabulous, intelligent, moving, and unusual concept. As an aside, but this is important, I came to the United States in 1980, a post-colonial Indian, fresh off the boat, not knowing the blues at all.* I’d heard jazz and rock, and, yes, I may have listened to Billie Holiday, but simply as jazz. I did not know the blues. In the early eighties, three young white people from North Carolina introduced me to the blues. A few years later, more white people introduced me to more blues. No African-American has introduced me to the blues, though one here, or one there, may have listened to a song with me. White Tears is about the blues. It is also about incarceration, racism, American government, guilt, and blaxploitation. I read it after J. Saunders Redding’s No Day of Triumph, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, also some Flannery O’Connor, but before Marilynne Robinson. This context is important because it reflects one thread of twenty-first century grappling with “race” in the United States: immigrants, especially non-white immigrants, consciously – intellectually and morally – adopting and owning the race history, and the racial present, of their new country, trying to find to find an American identity between, or beyond, the two easiest choices: “to assimilate into White culture or to appropriate Black culture.” ** The main characters of White Tears are two young white men and a vengeful black ghost. The two white men love music, particularly the blues, particularly the richer white man. The poorer man is adept with technology, the richer is a collector, and neither is good at navigating the moral delusions of human societies. Kunzru sets up a gorgeous plot device which begins with Seth’s hearing a song fragment while randomly recording street and other public sounds in New York City. It leads to a theft of intellectual property, of cultural property. We don’t know it, but the past is vengefully inserting itself into the present. We get a hint of mixed realities but the language of reality keeps us grounded in the present. The rich boy, Carter, gets beaten up and disappears into a coma, but we are not sure if all of that is real or a delusion. The remaining boy (Seth) knows that the attack on Carter has something to do with the theft of the song, but he believes that the threat will be dispelled if he can explain and prove the innocence of the prank. Meanwhile, he has geeky hots for Carter’s rich sister (Leonie), is conned by a journalist masquerading as a friend, and draws Leonie into the retracing of a tragically exploitative trip, during which she is pruriently murdered and he falls into his first full hallucination of white face-black face. From that point, the narrative spirals towards to the climactic integration of evil-innocence-cluelessness-privilege-death and subordination-suffering-incarceration-ghostsofChristmaspast. The problem with White Tears is it is not a tragedy. The bad people are unambiguously bad. Revenge is simple. The innocent are clueless, and cluelessness is not innocence. Kunzru’s story is very powerful, relating a national, indeed global, history of extreme exploitation, of capitalist and racist privilege, of systematic cruelty. This is a story of deep red and black strokes. The flaw in White Tears is that he tells it with deep red and black strokes, but he – diaspora brown, and post-colonial like me – does not have adequate color capacity for it. Coates tells it black and red, unrestrained, and sometimes tenderly, from his heart; he himself grows in the telling. Redding’s 1942 travel memoir is written with a post-War, pre-Civil Rights optimism. His telling is fluent and dispassionate, skillfully weaving literary English and the vernaculars of the southern localities he visited. With scholarly calm, Redding chronicles harsh and casual racism, and the human frailty of Southern Negroes (as they were called in the forties), whether beaten down by poverty and racism or, if well-off, struggling to reconcile racism and economic privilege. Americanah’s narrative goes from the ordinary color consciousness in a non-white, post-colonial, independent state – in this case Nigeria – to consciousness of racism in the United States, with a side journey into racism in England, and back to a twenty-first century globalized consciousness of race and color. Like Kunzru, Adichie writes with all of the skill and confidence of the educated post-colonial cosmopolitan. She claims all of the English language, and writing phenomenally, so to speak, claims all of the colors her novel can bear. She cheerfully presents us with types, and then just as exuberantly adds their ingrown hairs and pretensions. In the end, Coates, Redding, and Adichie write about flawed people loving, exploiting, or being clueless about flawed people. Held against them, albeit serendipitously, Kunzru writes about bad, or consciously false, people exploiting weak people. In White Tears, Hari Kunzru writes a superbly ambitious story. He manipulates structure, language, and plot both intriguingly and smoothly, and his characters are often perceptively drawn, although sometimes with more self-conscious irony than needed. However, in this brave effort to write about race in the United States without (simple) assimilation or (strident) appropriation, Kunzru loses his voice, and as a result no character is full, not as black, not as white, not as female, and not even as male (or other gender). The characters who are closest to being full are the two lonely older (white) men, JumpJim and Chester Bly who move through their ghostly parts in ways that are both lumpy and alive. They are not stock characters dressed up; they have shadows that allow me imagine into them. JumpJim shuffles and obfuscates in palpable ways while Chester Bly travels through the south like a lovingly-rapacious white doppelgänger of J. Saunders Redding. To the degree this review sounds critical, it is not about throwing shade on Kunzru for misappropriation nor is it calling on Kunzru to add a “brown” voice if writing about race in the United States. Rather it is a rumination on the difficulty of trying to write about race in the United States, where every word takes a stand and every word can be hurtful. One path to safety is to write what, at its fullest, is an uncontrolled narrative in a highly controlled way, where the writer is apart and in control always. The rub is that ‘to be in control always’ can only be achieved with a limited range of representations. This means that the writer risks being more on the mechanical end and less on the “live” – internally conscious, escaping, haphazard – end of narrative representation. As a South Asian diaspora voice, Kunzru writes very carefully about race in the United States. He is not afraid to personify the badness of racist capitalism and the will to vengeance of the historically exploited. But, in a curiously ironic way, while he makes the blues the heart of the story, he loses the pathos of the blues which is a human pathos. The whiteface-blackface-whiteface torment in Seth’s story comes the closest to pathos, but Seth loses palpability as his delusions are cleverly articulated. In the end, his delusions and hallucinations come across more as elaborately didactic representations of the delusions and hallucinations of racist capitalism than as human pathos that wends through will to/subordination to power, desire, suffering, love, weakness, and death, though not necessarily in that order. * For more on my slow, always incomplete, learning about race in the United States, see my blog post The Color of People. ** Mallika Roy, Hardly Un-American In the past it appeared that the engagement intention of art was to conjure a single bond, however illusory, between the viewer and art object before her. Supportively, the role of a curator was to present the art object in the best way to achieve that singular moment. Contemporary art, which seems loosely to be art created over my now-rather-lengthy lifetime, appears to have different and broader intentions, or perhaps these intentions have been laid upon it by the accelerated popularizing of art and the bolder actions of curators.* The curator in contemporary art seems to have developed into something between a composer and conductor, who orchestrates a dynamic multi-sense, multi-directional engagement between the art, context, and viewers, and invites the single viewer into a kind of performance which they** can choose to enact somewhat hermetically amidst wraiths, or somewhat chattily among other willing or unwilling members of an expedient ensemble. My most recent experience of contemporary art-watching happened in New York City, with a prelude visit to the Rubin Museum which presented “historical” objects in a winding, resounding, compartmentalized, but also fundamentally open and flexible, space. I went to the Rubin for the Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition and was properly astounded by the intensity of each photograph, each a composition by itself. I left the Rubin struck by the Buddhist iconography and sounds of the museum, which enfolded the more traditional presentation of the Cartier-Bresson photos, and conjoined easily the meditative, the erotic, the powerful, and the immanent. One could have chosen to visit only the Cartier-Bresson exhibition but that would have meant a deliberate shuttering of the senses, or an excision of a limited exhibition space – its photos, air, light, and walls – from a larger composition.*** The visit to the Rubin was a part of seven days of walking, working, eating, talking, thinking, and feeling in the city. The walking (around Williamsburg, the Village, from midtown to the upper west side, loitering, speeding, jostling), working (resisting and learning how to pitch and sell my first novel), eating (patatas bravas, Singaporean street food, Korean fried tofu, street dosas, a street hot dog, cauliflower tacos), talking (about politics, change, love), thinking (about strategy, living, composition), and feeling (the humidity of NYC summer, the grittiness of dust and burnt fossil fuels, the rhythm of slowness and speed sometimes under my control sometimes not) had inflated my sense of being, had created a sense that I had more, and more alive, nerve endings on a larger surface area. Wrought by this urban stimulation I went to see the Lygia Pape exhibition in the Met Breuer. This long, wandering introduction to a deliberate exhibition in an angular building is because my engagement with the Pape exhibition was primarily about movement; and movement implies, indeed requires, space and context. I went into the Breuer building and bought an annual membership (with a discount for being from far away), for I have been there before and will go again. Then I chose the stairs to revisit the curiously halted viscosity of Dwellings by Charles Simonds, a vestige from the Breuer building’s Whitney days. I climbed up to the floor with the Pape work and entered to a sideways view of the splash titling and image for the exhibition – A Multitude of Forms. The image combines uniformity – whiteness, children’s heads, all about the same size – and variation – in the way the white cloth dips and rises, in the very difference of each child. It is an exuberant and sobering image, conveying constraint, concealment, emergence, and movement. Only later did I realize that the image is a still from a movie which I viewed, and remember, as part of a course that included simple geometry – of the building, of Pape’s early work with the “geometric forms and pure colors” of the abstract art of the Grupo Frente; included, also, her later experimentation with naïve, semi-ethnographic film; and, finally, her return to geometry but now with pieces of unrestrained size and expression that jutted into the large spaces of the Breuer. The Breuer building enforces attention to perspective and the curator fully uses the building’s windows, ceilings, walls, and doorways to shift perspective from the singular art piece to the space, to the oeuvre, to other live bodies, to the outside in time and the outside in space, to both the merging of self through projection of self into something external and to the shocked separation of self from the exploitation of an image or a texture, both intended and unintended. My own movement was core to my viewing of this art, but, in addition, the movements of others became part of the art object in my viewing. One of the didactic plaques explains about the “Neoconcrete” tradition and intentions of Pape’s later work that “among the most influential outcomes of Neoconcrete art is the notion of an open work subject to the contingencies of time, space, and viewer participation.” It was humbling to find myself a textbook viewer of Pape’s art. I left the floor feeling like I had walked through a life, or in a long procession, more actor than spectator. Following a quick visit back to Dwellings, now merely landscape, I entered another show, THE BODY POLITIC, four experimental videos in dark places beyond an empty space: Five Easy Pieces; Phat Free; Love is the Message, the Message Is Death; and (down a corridor, separate) NoNoseKnows. In part because of time constraints, in part because the opening space seemed to offer me only two options, IN or OUT, and in part because I was already full, I gaped eagerly at the notices for each film and left the floor. Excision was easier in this geometric building than in the Rubin building.

I went down to the basement looking for an outlet to charge my phone. After an excellent cup of tea, I returned to the street, moving – mostly forward, sometimes sideways, sometimes halting, stepping back – and observing as if my path was still curated, almost as if each object was still art and I was still performing. * My interest in contemporary art and sensitivity to curatorial work has been deeply influenced by my artist friend, Patti Fox, and my curator/artist daughter, Pia Chakraverti-Wuerthwein. ** After years of railing against the singular “they,” I have been convinced that it is a more inclusive pronoun than s/he. It is also more commonly used than my logically preferred pronoun “ze.” *** I have no photographs of the Cartier-Bresson exhibition because photography was forbidden in that section. Over a decade ago when I was going through a melancholy phase, I began to sit with a Zen meditation group. I get melancholy when I cannot resolve something important to me, when there is no solution that I can generate in an ordered way. When I am melancholy in this way my mind gets stuck on a treadmill of the same questions, the same arguments, the same words, the same dead-end fogginess over and over again. This is a mental state well-suited and challenging to meditation. So to help me focus – the restraint of counted breaths usually frays and falls apart with the pressure of the treadmill -- I conjured a brief mantra of the capacities I wanted to bring forward to keep myself sane: strength, integrity, compassion. These capacities would help me jump off the treadmill both while meditating and in general. So whenever I found myself distracted or morose, I repeated these words, standing (or sitting) straighter, feeling simpler, bowing to the person or persons who were the apparent causes or objects of my distress. As the causes for that distant melancholy faded, in part because of my own and others’ actions and in part because the world turned, I stopped reciting those words as frequently. For a long while I stopped regular meditation.

Then, as an empty nester, I returned to meditating with the same Zen group, not as regularly as those many years ago, but often enough. A few days ago, I saw the Dalai Lama with a group of no more than 200 people. I was in the third row, in the center, and could see him as an ordinary old man – his expressions, the folds of his skin, the slowness of his movements – while he spoke as one of the most influential figures of the late 20th century and the early 21st century. Among other things, he spoke familiarly about the importance of the calm mind and the unhealthy effects of anger and fear. So when I went to meditate on Monday and “strength, integrity, compassion” drifted into my mind I felt good about my calm mind and my rejection of anger and fear. Wanting to update my mantra I thought about the capacity I would want to add, and alighted on the elusive and unlikely (for me) capacity for sweetness. I repeated “strength, integrity, compassion, sweetness” with brave complacency, knowing that sweetness was something I would have to strive for. Then my mind, ever-unmeditative, started thinking about incompleteness, imperfection, and what of myself I was excluding and I found myself building and repeating: strength, weakness, fear, shame, integrity, confusion, inconsistency, scattered-ness, dishonesty, compassion, anger, hatred, sweetness, bitterness. I had to face all of the excluded and found that while I had all apparently under control, all lived in me, not all to the same degree at this time and some (like bitterness) very little at any time, but if I have strength, I have weakness, fear, and shame; if I have integrity, I have confusion, inconsistency, scattered-ness, and dishonesty; if I have compassion, I have anger and hatred; and if I have (a little, sometimes) sweetness, I have (a little, sometimes) bitterness. Somehow this relieved me. There is nothing to hide; I have nothing to hide. And how does this relate to beauty? Well, while I was thinking about what to add to my original mantra, I thought about adding “beauty.” But beauty isn’t a capacity, it is a kind of presence, and once I faced (some of the) excluded, felt relieved with open imperfection, I thought this I can call beauty. Depending on what the beholder chooses to emphasize, Emmanuel Macron looks a lot like Barack Obama, or looks vastly different from Barack Obama. Among the similarities: both the men started out as young upstart contenders for head of state of a powerful country; both have degrees from elite universities; both have a literary sensibility; both are comfortable with the globalist and tech-savvy zeitgeist of the 21st century; both have been deeply influenced by strong women in their lives; and both are socially progressive and economically centrist, or, for many critics, “neo-liberal.” The most notable difference is that Barack Obama, with an African parent, has a fundamental aspect of identity that is not aligned with the whiteness of the traditionally standard “American” of colonial America and the independent United States while Emmanuel Macron is gloriously standard white “French,” as he himself puts it “a child of provincial France.” One further difference, that is crucial though small, is that Obama’s course to politics took him through an intense phase of community organizing while Macron’s took him through successful international banking.

But why the comparison? Because there is one further, and major, similarity. Obama offered hope and optimism to the United States, in which a core population was beginning to express its growing disaffection with the inequalities of globalization. For all his successes, a substantial portion of this core population believed he failed them and their disappointment contributed to the election of Donald Trump. Like Obama, but at a later stage in the decline of the heartland industries of the West, Macron offers optimism to France. He is heard more skeptically than Obama was, in part because of the perceived failures of the last decade, in part because he is perceived to be aligned with globalized financial elites (no community organizing in his history, remember), in part because his political experience is much less than even Obama’s was, and in part because he does not have Obama’s oratorical skills. Now, in 2017, Macron may well become President of the Republic of France. In the last days before the first round of voting, he posted an amusing video on Twitter – a call from Barack Obama, who wished him well. In a significant way, Macron, if elected, will inherit or will have the opportunity to inherit, Obama’s mantle. If he becomes President, he will need to engage the deep reformism that Obama only partially engaged. With the world economy growing again, he will be both in a stronger position than Obama in 2008 and will face a real possibility of initiating the end of both the European Union and the Fifth Republic if he fails. Marine Le Pen’s gains on her father’s electoral successes, and her support from a large proportion of French youth (who face an unemployment rate above twenty percent), are striking and if a Macron Presidency is experienced as ineffective the next President of France might well be Le Pen. So what does effective mean in this context? It means reconciling the gains of 21st century globalism and technology – which are redefining culture and redistributing work – with a real renewal of “la France profonde,” not just as a relegated patrimony but as areas of restored economic activity and cultural relevance. It means harnessing the technological drivers of economic growth in the 21st century without losing a practical commitment to human dignity as a social value in itself. It means renewing the cultural centrality and economic viability of French autochthony and ethnic whiteness while integrating the colors and cultures of non-white French communities. It means domestic transformation while managing the constant encroachments of a complicated world: a flawed European Union and euro zone; murderous acts committed by militants, including French citizens, who call themselves Muslim; a Russia that seems to want to return to world power status through covert activities as well as alliances with alt-right groups; a global economy that is decentralized and nimble; and a planetary ecosystem that is in great danger. Does Macron have the ability to be bold, to listen, to build alliances across political boundaries internally and externally, to identify core purposes and remain steadfast when he, inevitably, faces opposition and failures? For that is what it will take. Obama had the same opportunity, along with the complications that were particular to the time and place of his Presidency. Macron, if elected, will lead a new round of a fateful and sensitive experiment: can the paradigm shifts propelled by economic globalization, technology, demographic changes, and climate change be reconciled, peacefully and productively, with the affect of deep-rooted national identity that is correlated with white-European ethnicity that has enjoyed a seven-hundred-year ascent to geopolitical dominance but is now on the decline? Or is violence – whether direct or hidden, whether to protect or to exclude – inevitable? Note: This piece was written on 4/26/2017. On May 4, 2017, a video endorsement of Emmanuel Macron by Barack Obama was made public. In the spring of 2012, I watched The Hunger Games. I was horrified by the story. I hadn’t read the books, though my daughter and nephew and millions of others had. I knew it had a strong female hero and so I expected to like it. But then I found that the core story involves a gladiatorial competition between children, where the winner is the one who survives. The weak, usually the youngest, get picked off first. What mind conceived of this horribly implausible game, I wondered. Never in history, to my knowledge, had any ruler or regime instituted such an entertainment. Yes, children were wantonly killed; yes, people were killed by (adult) gladiators; yes, child soldiers killed and committed atrocities in a “war.” But this pitting of children against children for entertainment made no sense, fit no pattern that I could think of, though it was a compelling story to follow and watch, much like a horror film. It wasn’t implausible in the way a superhero movie with bogus science is implausible, it was implausible because the social premises seemed off.

The only way it made sense was as an allegory. I moved back from the immediate spectacle of bigger children killing smaller children in a lush game world and considered only the most basic scaffolding. The story is set in the country/world of Panem which has twelve districts surrounding the capital. The districts are punished annually for a long-past insurrection by having to give up a child to fight in the Hunger Games. The capital is a beautiful city with wondrous technology, extravagant foods, fascinating clothing. All in all it expresses a climactic moment in human design and artifice. The richer districts are close to the capital and the poorest is far away. Typically, the expectation is that a child from the richer districts, usually one of the older children in the competition, will win (killing or otherwise out-surviving the others). So, with what framing could I find children surviving by killing or out-surviving other children plausible? Looking at the structures of my life, I am close to the centers of power and wealth, not geographically but in class terms. I enjoy some of the ease and luxuries that are increasingly taken for granted, and often further rarified, in those centers. My children have tremendous access to opportunities of various kinds. No, of course, they aren’t like the competitors of The Hunger Games, my mind shies away from the thought, but out there are children, even in the US, who have much less, and further out there are millions of children among the 20 million people who are at risk of starvation, right now in 2017. Our children do not choose these roles. It is as adults that we acquiesce to these structures, with those of us who are closest to the centers of power and privilege acquiescing the most. It’s very difficult not to acquiesce as an individual. The system supports, and is supported by, a web of daily tasks and pleasures. I could pay more taxes. I could give more money to worthy organizations. I could work in public service jobs. I could volunteer. In all these cases, my individual actions can easily be lost or get wrapped into the same-old. It’s not just a case of feeding the twenty million enough that their dead bodies don’t saturate our newsfeeds; and, then, once this crisis is past, we would leave them to a deprivation that is one notch above death. As an allegory, a plausible one it turns out, The Hunger Games helps us see the problem in our own lives, but it doesn’t help us much with a solution. In Collins’ trilogy, Panem’s socio-political structure is maintained with hidden (and not so hidden) violence and trauma, and then is, itself, overturned with extraordinary violence and trauma. We have our own hidden, and not so hidden, violence. But I cannot hope for the extraordinary violence that drove change in Panem. So, in the dull way of ordinary work and long-term trajectories – not just of policies and numbers, but also of relationships and accountability – how do we, in the US, look past one or two elections (2018! 2020!) to a larger, longer-term shift from the inequalities and hidden (and not so hidden) violence of our world? How do we work for this shift across political boundaries? Or can we hope only to hold back the worst extremes? Twenty million people are facing famine now. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed