|

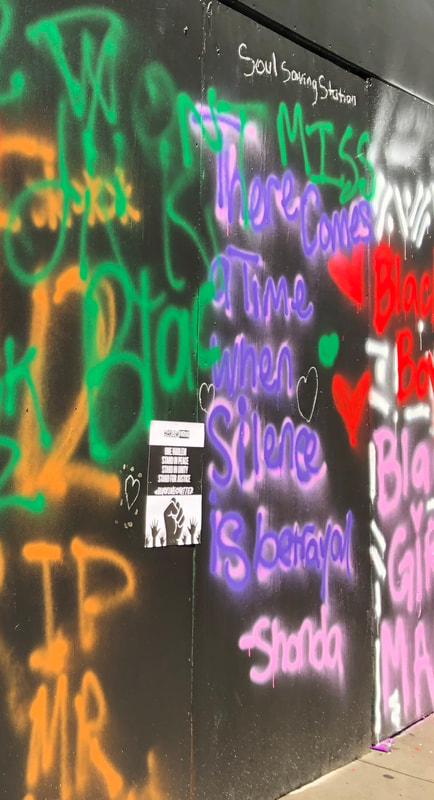

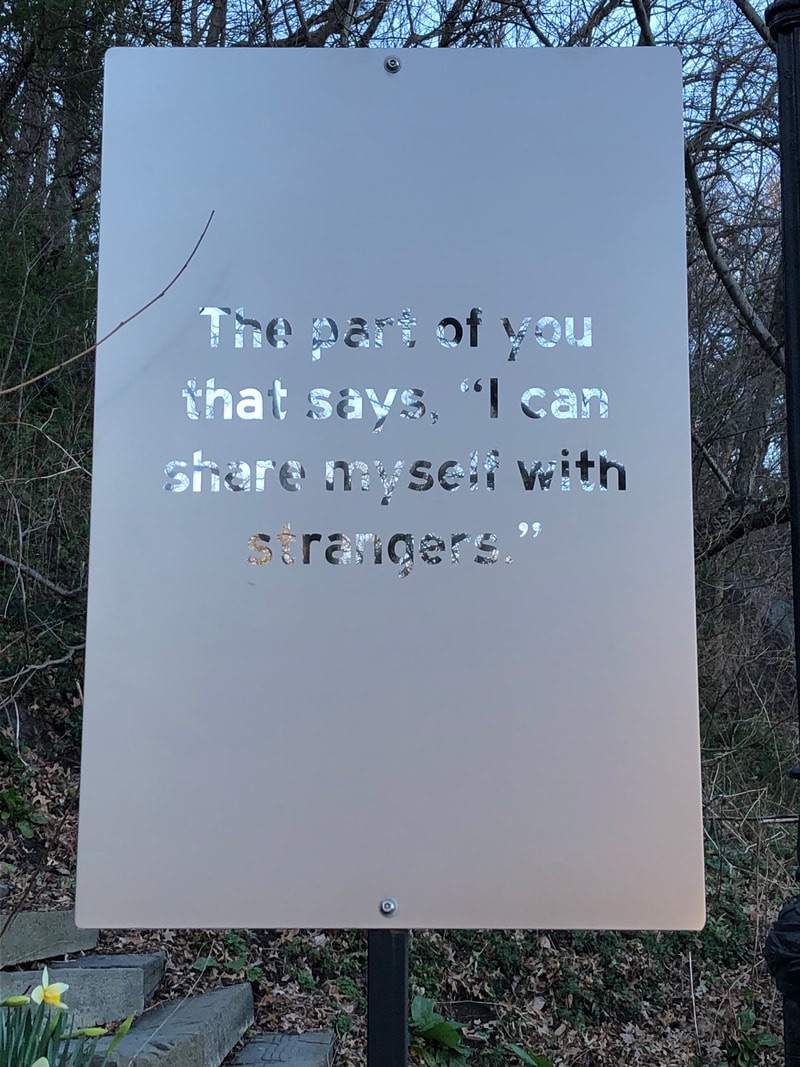

Note: The title of this blog piece is exactly the same as, taken directly from, a book by Alice Walker. I have not yet read that particular book, so this blog piece does not refer to its content directly. I have read other work by Alice Walker. The story of how Alice Walker’s title-phrase came to me is in the blog piece below. As the contours of this blog piece have emerged over the last two weeks, it became increasingly clear that this was the right title for it. On May 22, a little less than three weeks ago, my eye was caught by the tagline of an op-ed article in the NYT:* “Better to love your country with a broken heart than to love it blind.” The title of the article was Germany’s Lessons for China and America. The tag line was drawn from something the current President of Germany, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, said in relation to the 75th anniversary of the end of WWII in Europe: “Germany’s past is a fractured past — with responsibility for the murdering of millions and the suffering of millions. That breaks our hearts to this day. And that is why I say that this country can only be loved with a broken heart.” I have seen this phenomenon of loving, or struggling to love, with a broken heart in myself and in others, in relation to people in our lives and in relation to the communities and countries we call “mine” and which have shaped us. People who live in dominant majority communities, as I did growing up Hindu in India, sometimes take a while to feel and understand this phenomenon of broken heart in relation to one’s larger community/country. It took me layers of learning, layers of foolishness, over decades. In 1980, I came to college in the United States, like most people having had some personal challenges (practical, emotional, existential) but generally comfortable in my external identity of (majority) Hindu, well-educated (class-privileged), Indian (heterosexual) woman. Yes, I was vocally feminist and spoke up against injustice as I saw it, but in both cases I felt largely secure in who I was, and surrounded and supported, sometimes prodded, by feminist/left-leaning forebears and peers. My first somewhat conscious encounter with what I might now call loving one’s larger community with a broken heart I remember with shame. I asked another student at my college who was Jewish Iranian whether she felt more Jewish or more Iranian. It was a genuine question and I was struck (silent!) by how much it seemed to hurt her. I did see and hear how deeply that question evoked a negative reaction. It both seemed to miss the point and deeply hurt her. I didn’t know myself well enough to know how to seek further understanding. I never got to know her well enough to come to an interactive understanding of myself and her through the foolishness of that question, and so this retrospective understanding on my part is still partial. Her understanding may or may not coincide with mine. Fast forward to the mid-nineties. I was waiting for my older daughter’s pre-school day to close, just sitting in some random outside space when I was joined by some random man. We started chatting. It turned out he was Jewish and had grown up in Russia. I don’t remember the details of the conversation. He was an erudite and eloquent man and we spoke about Russian literature and music. He knew a lot more than me, which I always love. I don’t remember any details. What I do remember is how deeply he loved Russian literature and music and how much he hated Russia. When I read Roger Cohen’s May 22 piece, I recognized what Steinmeier said. I’m not sure all Germans consciously feel what he expressed, but the question of how you love your country and by extension yourself is a live one for all Germans since WWII, I believe. It took the Holocaust and WWII to make that majority community contend with its own broken heart, to feel the violence embedded in who it is, to see that violence, to face the emotional violence that it has generated and potentially generates, and to struggle with how to love and to love itself with that broken heart. I use the collective “majority community” and the impersonal “it,” but this plays out in individual people, individual hearts, each in its own way. Usually when emotional violence is committed – often enough but not always accompanied by physical violence – the bulk of the resulting emotional work is left to those who suffered and survived the violence, with such effects extending to their loved ones, their descendants, and their communities. The experience of emotional violence and its effects are most obvious in, and to, those who are on the receiving end of such violence, but it also affects, profoundly, the soul and integrity of everyone in that system, whether direct perpetrators, witnesses, bystanders, or those who turn away, dissociate themselves. Fast forward again to about two weeks ago. Angry, heartbroken, and feeling helpless after the video of Amy Cooper in Central Park and with news breaking on the killing of George Floyd by a police officer openly in the presence of other police officers and ordinary people – neither of these new or unusual events – I was conversing with a writer friend, thandiwe Watts-Jones. I spoke about my own anger and heartbreak. I mentioned the Roger Cohen article and the Steinmeier quotation, focusing on the phase “this country can only be loved with a broken heart,” and she pointed out that Alice Walker had written, “the way forward is with a broken heart.” Of course. Today, I am a citizen of the United States of America. I have lived in this country for forty years, about two-thirds of my life. I have been a citizen for a little over fifteen years. I love this country and I am deeply critical about many things here: many of our policies, our current President, the stark structural inequities of our society and economy; and our resistance to facing the physical and emotional violence, particularly to Native Americans and African Americans, that is centrally part of our heritage. I love the music and artistic work of Americans.** I love the brashness of American culture. I love the way Americans come from all over the world, as a result of which we live with immense complexity. I am proud of the stated Constitutional commitment to “freedom, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all.” I became a citizen when I realized that while I am very opinionated politically, I had never voted in any country. I left India before I started voting, and then for more than two decades lived in the United States as a “legal alien.” What this meant was I referred to “you Indians” when I criticized something in India, and “you Americans” when I criticized something in the US. One of the central reasons I became a citizen was to hold myself politically accountable. I didn’t vote for Donald Trump, but I am accountable for the government of the United States. From that sense of political accountability I have grown to know that, as an American, as a citizen of the United States, I also hold accountability for the history of the United States, for what it means to be American, including the hegemonic intonation of “American,” and including the emotional and physical violence of my heritage as an American. What I am as an American today, even being a relatively recent immigrant of color, is also founded on dispossession of Native Americans and the continuous weave of slavery, racism, and anti-Blackness in our history. For several centuries until right now in 2020, we Americans have allowed African-Americans to carry disproportionately the risk of death and other physical violence as well as most of the emotional burden of slavery, racism, and anti-Blackness in our culture. Some form of color- and race-related anger and heartbreak is chronically part of African-American lives. African-American writers and speakers have told us this repeatedly. They’ve told us how their children are taught to watch out for and avoid the risk of being killed, and to expect and overcome risk of humiliation, all this only because of their “color” and “race.” And they’ve taught themselves and their children how to love themselves in the face of indignity that is often intended, sometimes unwitting, how to love themselves and this country with a broken heart. One outcome is that African-Americans have done some of the most extraordinary soulwork of any group of people at any time in history.*** The rest of us – not just Americans, the world! -- have drawn on their soulwork, expressed in music, writing, art, and inspirational leadership. Martin Luther King Jr, Audre Lorde, Malcolm X, Zora Neale Hurston, Frederick Douglas, Oprah Winfrey, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Ta-Nehisi Coates, bell hooks, J. Saunders Redding, Alice Walker, Langston Hughes, Rita Dove, Ishion Hutchinson, Jesmyn Ward, Kendrick Lamar, Nina Simone, Gil Scott Heron, Shirley Horn, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Abbey Lincoln, Jimi Hendrix, Janelle Monae, John Legend, Meshell Ndegeocello, Kamasi Washington, Regina Carter, Noname, Chance the Rapper, Tierra Whack, William H. Johnson, Betye Saar, Romare Bearden, Bisa Butler, Nari Ward, Ja’Tovia Gary, Spike Lee, Simone Leigh, Jeremy O. Harris, Lupita Nyong’o. I could go on. I know some of the work of every one of these people. These are just a few of the African-Americans whose work I have experienced as immensely generous to me and to the world. This brief video made by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre illustrates what I am trying to tell you in this paragraph better than anything I can say.**** Last Christmas, I gave my two daughters Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider, in part because they might learn something about being American and being feminist, but mostly because Audre Lorde is a profound guide in soulwork for anyone, anywhere. When I read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, I suggested that any man should read that with his son. It’s a hard book if you are “white” and live the “American Dream,” but if you get past your defensiveness you will see it is also about engaging with the complexity of the world, about heartbreak, about loving and nurturing and protecting your child in the face of complexity and heartbreak. If you feel into your defensiveness, you will learn a LOT about anti-Blackness in the United States. In ordinary ways many of you – across the world! – draw on the African-American lyrics and music of spirituals, blues, jazz, soul, and rap to engage and understand your own heartbreaks. African-Americans have done the bulk of the emotional work of our country for too long. Over the last few weeks, as our country increasingly convulsed with pain and protest, the rest of us are beginning to pick up our share of the emotional work, our share of the effects of the emotional violence of racism and anti-Blackness. This isn’t just about empathy from the outside – often forms of what Dr. Kenneth Hardy calls “privempathy” – but eventually about learning to feel that wherever you are in a system that breaks someone’s heart, tending to their heartbreak means recognizing your own broken heart, the irrevocable break in who you are, and learning to love, and protest (and make policy changes! and change our culture in fundamental ways!) with that broken heart. [ADDED NOTE: I was corrected by a reader: “privempathy” as referred to above is not merely empathy from the outside but is the “hijacking” of the experience of an African-American by empathizing through one’s own (privileged) experience of some form of hurt/subjugation. The notion of “privempathy” is described in this summary of Dr. Kenneth Hardy’s very compelling, and challenging, approach to cross-racial work. In some ways, the generalization of broken heart work in this paragraph may be interpreted as a kind of privempathy. Please see the end of this blog piece for a longer/larger clarification of what I mean as I call for this 'broken heart' work around anti-Black racism in our country.] Broken heart is a beginning. For Zen and Leonard Cohen fans, it’s the crack that lets in the light. A week or so ago, I wrote to a colleague, someone I don’t know well, about my (and shared) anger and heartbreak. I added an apology in case he felt I was overstepping into the personal. He wrote back that “reaching out with a loving heart is never overstepping.” When I recounted this exchange to another colleague and dear, dear friend, he commented that this exchange illustrated stepping into being vulnerable with a broken heart and open with a loving heart. This isn’t easy and often I feel foolish, and sometimes I’m told I’m foolish, or even downright wrong, directly or indirectly. If you have read thus far, some of you are probably saying, yeah, yeah, but what do we DO?!! I do believe that soulwork is essential, but as Audre Lorde said to her African-American sisters: “And political work will not save our souls, no matter how correct and necessary that work is. Yet it is true that without political work we cannot hope to survive long enough to effect any change.” She made that call to her sisters in the early eighties. Now in 2020, I say to my fellow Americans who are not African-American, while political work will not save our souls as Americans, extensive political work is needed to keep African-Americans alive and have equal access to good health and opportunity for “the pursuit of happiness.” Even today, June 10, 2020, African-Americans routinely face systemic inequity in education and healthcare, and discrimination in work places and public areas. They face very significantly disproportionate risk of death and indignity at the hands of police as well as non-police community members, and historically such acts of physical and emotional violence have tended to go unpunished or minimally chastised. The protests after the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, which followed the stark demonstration of structural inequality in COVID19-stricken New York, suggest that we may have come to a major turning point. Some of my thoughts on what is to be DONE are below, but first a note addressed to immigrants of color like me. This blog piece is written for all non-African-American citizens of the United States, but here are a few words for immigrants like me who are not white. While we may have our own experiences with racism and colorism both within and among us, and as we engage with fellow Americans, we also own the history of anti-Blackness and racism towards African-Americans. That racism and anti-Blackness is deeply our heritage as Americans. As my niece Mallika Roy taught me, we can’t just assimilate to some form of “white privilege,” or appropriate the African-American experience of racism as our own, or just sit out of this enormous political, cultural, social, and economic question that dates back to the earliest years of our country. To get us started, here is a great letter written by Asian American children to their parents four years ago, in 2016. So, now, some thoughts on what is to be done: -- Speak up -- VOTE!

-- Support activism and campaigns to change policies, government apparatus, and political leadership to

-- Pay attention to inclusion and exclusion, both implicit and explicit, in your workplaces and communities.

-- Do soulwork to understand better what African-Americans have suffered, learned, and given to the world; and to examine your role (you, yourself, as well as the you that lives out of complex and long-developing heritages). Carry some of the burden of the emotional work related to the physical and emotional violence of racism and anti-Blackness that African-Americans have carried for generations.

-- Don’t run away. It’s hard to live with what you can’t solve and with the pain of inequality, the pain of your own privilege and someone else’s suffering, to live with a seeping guilt (avoid that!) of your heritage(s). But, really, don’t run away! -- In the end, be guided by the excellent three steps offered by Maria Ressa, a journalist from the Philippines, in the graduation speech she gave in May 2020.

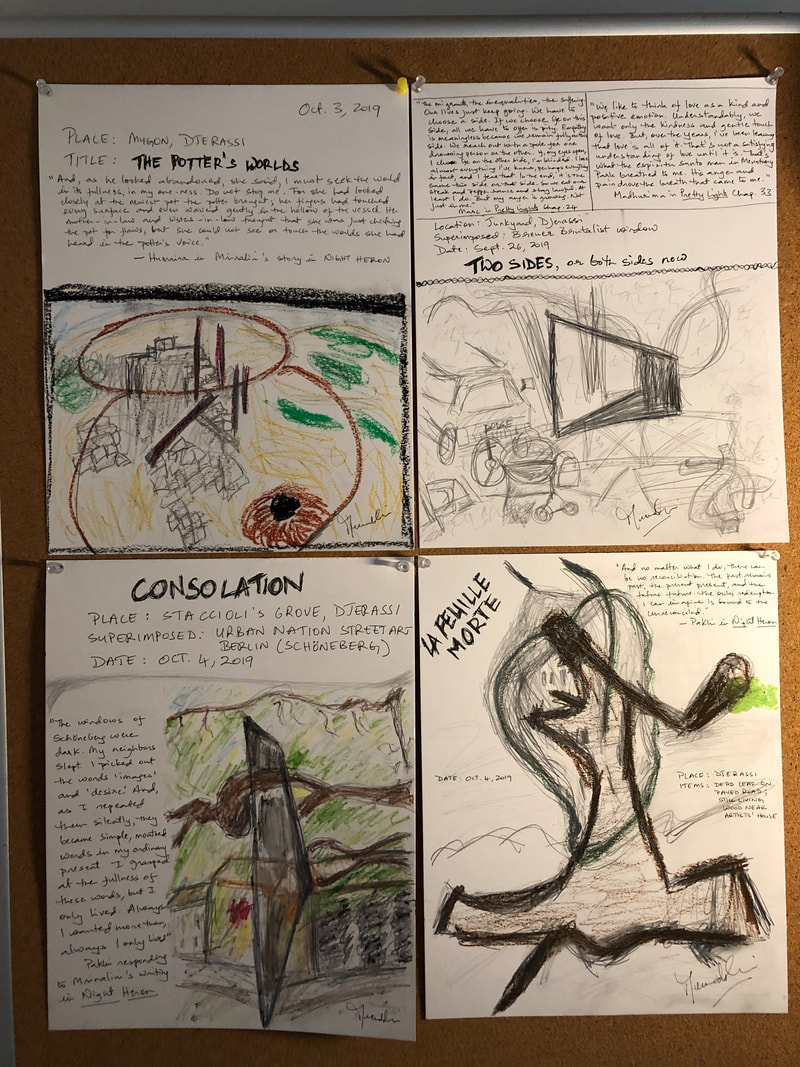

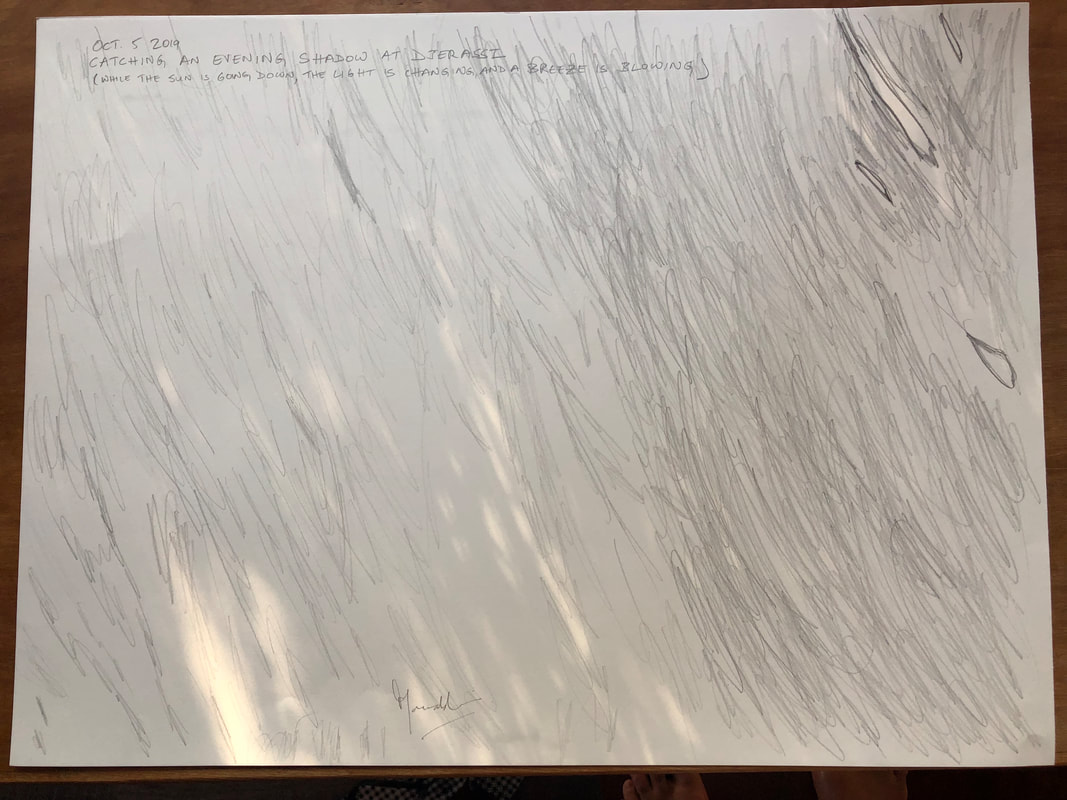

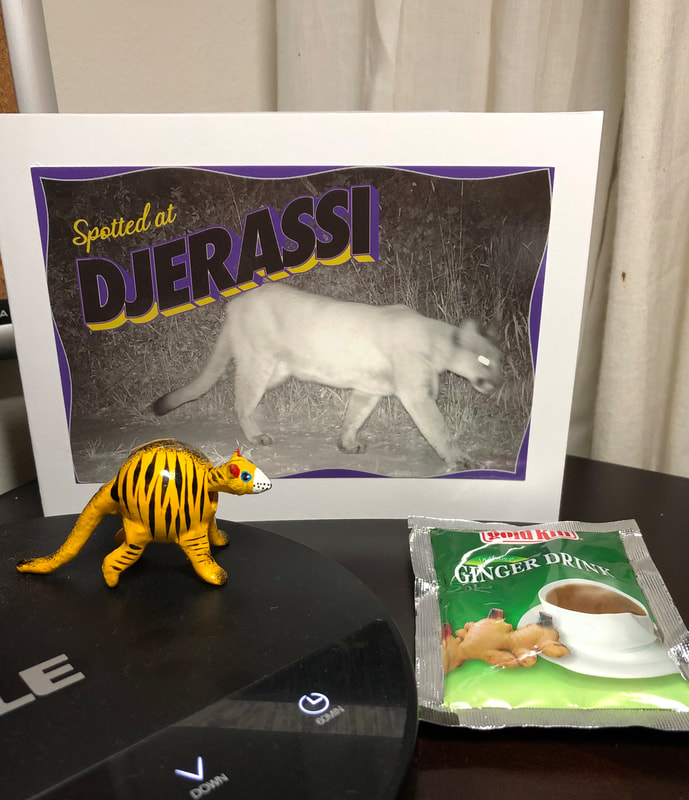

Acknowledgements: If you know me you have probably shaped what I’ve written here and/or heard some versions of this. If you see yourself in this piece, you probably are in it, even if I haven’t named you explicitly. That said, I started on this path most consciously in San Diego where there are particular people who have guided and pushed me in extraordinary ways. These include: friends and colleagues among the organizers, faculty and fellows of RISE San Diego’s Urban Leadership Fellows Program particularly in 2018 when I was on the faculty; staff and members of USD’s group relations conferences, particularly of the On the Matter of Black Lives conference held in March 2017; and finally words aren’t enough to acknowledge the guidance, patience, knowledge, and loving hearts of my dear, dear friends Zachary Gabriel Green and Cheryl Getz, and also Henry Wallace Pugh who has stood beside Cheryl for as long as I’ve known her. Of course, that doesn’t mean they would endorse what I have written here. These are people I have grown to love, which is the full face of gratitude, but I am still learning, still making mistakes, still working through my own cluelessness. _____ * The NYT is still figuring out what it wants to be in the 21st Century, as we fell into a Trumpian age that I hope we are clambering out of now. The NYT is not alone in this, but as one of the most prominent news organizations in the world, its spinning across torment, sentimentality, overwrought opinion, (rarely) humble offering of information, portentous screeds, and occasional brilliance affect us all. After all they are not a blog! And yet I read and learn from their articles. In many ways they represent and express a swath of our zeitgeist. ** This is a good time to acknowledge that I use the word American as the most quick and convenient designation for those who seek the benefits of, and carry accountability for, being citizens of the Unites States of America and as an adjective pertaining to their lives, activities, and creations, but I am aware that in the context of US domination in the Americas, “Americans” may intone and express a sense of US hegemony in our hemisphere. *** I learned the word “soulwork” also from thandiwe when she referred to the work – “soulwork” – of the Eikenberg Academy founded and directed by Dr. Kenneth Hardy. The word may have a longer history, but I learnt it from thandiwe and Eikenberg. I receive it as an evocative word for emotional work that goes deeply into what it means to be human, filling out and beyond, with great beauty and expansiveness, the more standard “life of the mind” that tends to get foregrounded in the “Western” (“white” or Euro-American) traditions. **** I haven’t written about influential African-Americans in sports because I don’t watch or follow any sport, and don’t really know enough about any particular person in sports. Note of clarification added June 17, 2020: A question from a friend who read this post led me to write this clarification. There are two pieces to this clarification. First, while it is written for anyone interested in reading some of my (still learning/still developing!) understanding of anti-Black racism in the United States and what needs to be done now, it is addressed primarily to non-African-American citizens of the US. Secondly, and very importantly, African-Americans don’t need to be aware of broken hearts and loving this country with a broken heart. They know this already! Their hearts have been broken over and over and over again for more than three centuries. And yet in 1955, James Baldwin wrote in Notes of a Native Son, “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Then in 1984 he had the following exchange with an interviewer for The Paris Review. INTERVIEWER “Essentially, America has not changed that much,” you told the New York Times when Just Above My Head was being published. Have you? BALDWIN In some ways I’ve changed precisely because America has not. I’ve been forced to change in some ways. I had a certain expectation for my country years ago, which I know I don’t have now. INTERVIEWER Yes, before 1968, you said, “I love America.” BALDWIN Long before then. I still do, though that feeling has changed in the face of it. I think that it is a spiritual disaster to pretend that one doesn’t love one’s country. You may disapprove of it, you may be forced to leave it, you may live your whole life as a battle, yet I don’t think you can escape it. These thoughts and sentiments have been expressed in word and action by many, many other African-Americans. So, no, African-Americans don’t need to be aware of broken hearts and loving this country with a broken heart. They know this already. It’s the rest of us (not Native Americans, who suffered violence and dispossession in the founding of this country, and who like African Americans have carried the burden of that emotional and physical violence) who might want to consider how we, as Americans, are broken. That, yes, we aspire to “land of the free,” AND that that aspiration also is based on a history of cruel dispossession and violence. This is not work for African-Americans to do nor do they need or want to help us do this work. This is our work, the rest of us, most of all white/Euro-Americans, but the rest of us as well. What African-Americans do need and want is for us to make our American culture and institutions less life-threatening and blocking to them. This is not about being sorry for African-Americans; they do not want or need us to be sorry for them. A couple of days ago, Imani Perry wrote a powerful and beautiful article in The Atlantic on this. Do read it. So then, what do we do with being aware of our brokenness as Americans? I don’t know. We’ll live some answers and then modify them as we see the effects of those answers. I think if we are more consciously aware of our brokenness – which cannot be erased, which is a core part of our history as citizens of the United States – we will shift our culture and institutions from the systemic injustices that arose from our violent history and we will love ourselves and others more fully. If you doubt love has anything to do with this, here’s something that James Baldwin wrote: “Love does not begin and end the way we seem to think it does. Love is a battle, love is a war; love is a growing up.” —from Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son (1961) Read James Baldwin, if you haven’t already. Every time I read James Baldwin I learn something about myself and the world. The focus on emotional and physical violence against African-Americans does not mean that other forms of discrimination, exploitation, and injustice don’t exist, or that economic systems don’t exacerbate climate change with all the effects it will have on vulnerable populations and ecosystems worldwide. I believe, though, that not only is eliminating the gross perniciousness of anti-Black violence way overdue, these various areas of systemic dysfunction are connected, and anti-Blackness is both a foundational element and one of the most terrible manifestations of linked injustices that have built up worldwide over centuries. I believe the building of concerted awareness and action against systemic anti-Blackness will vitalize other critical movements for change.

1 Comment

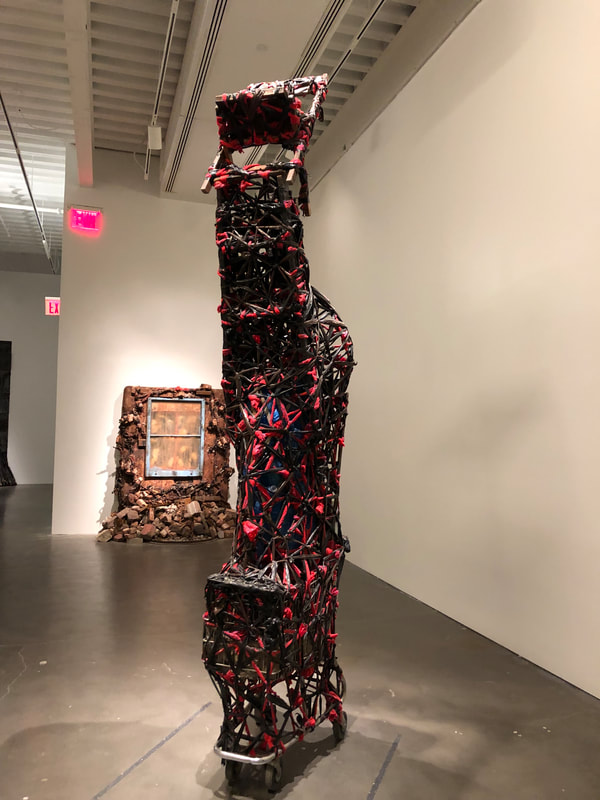

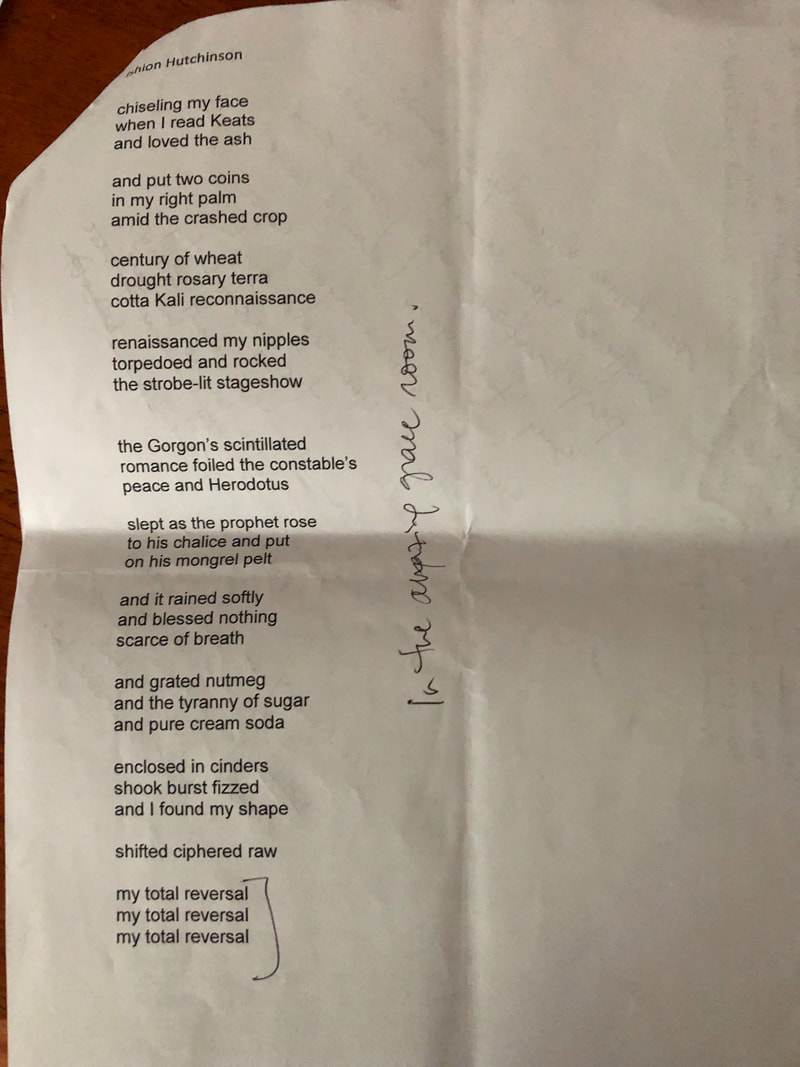

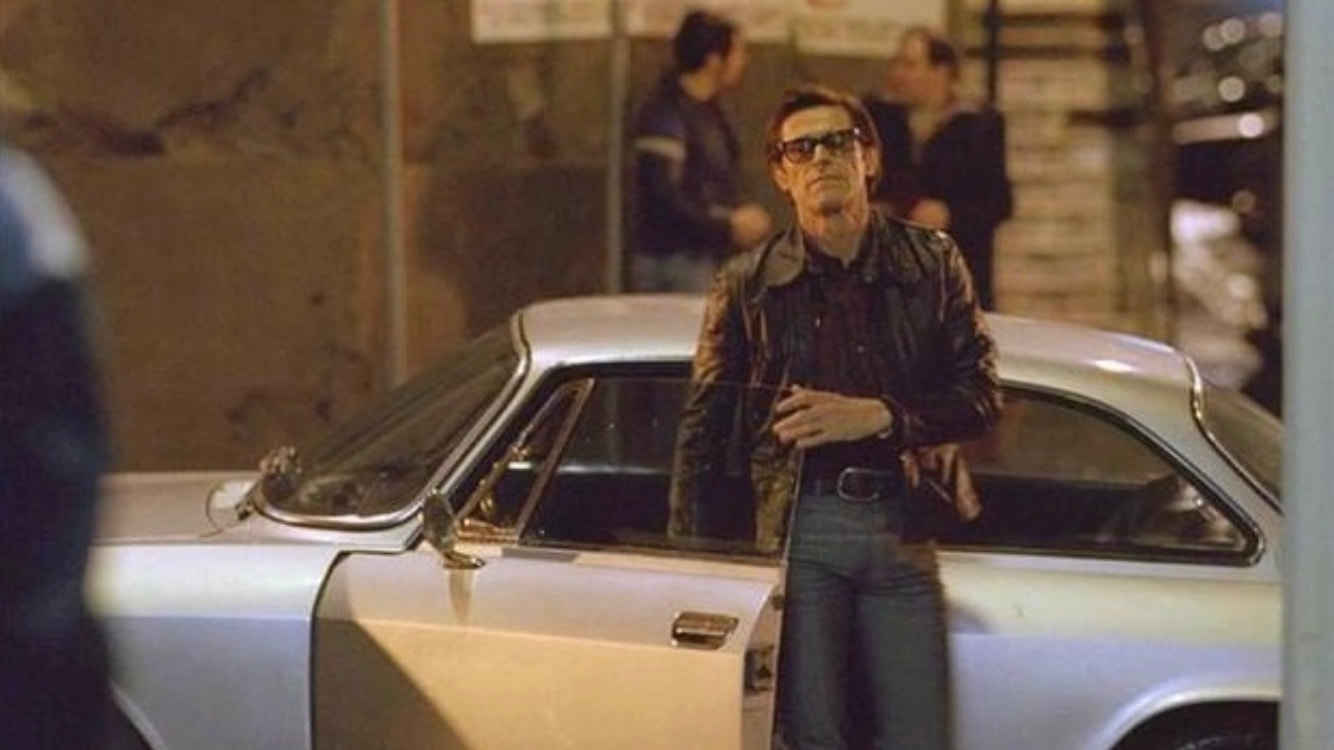

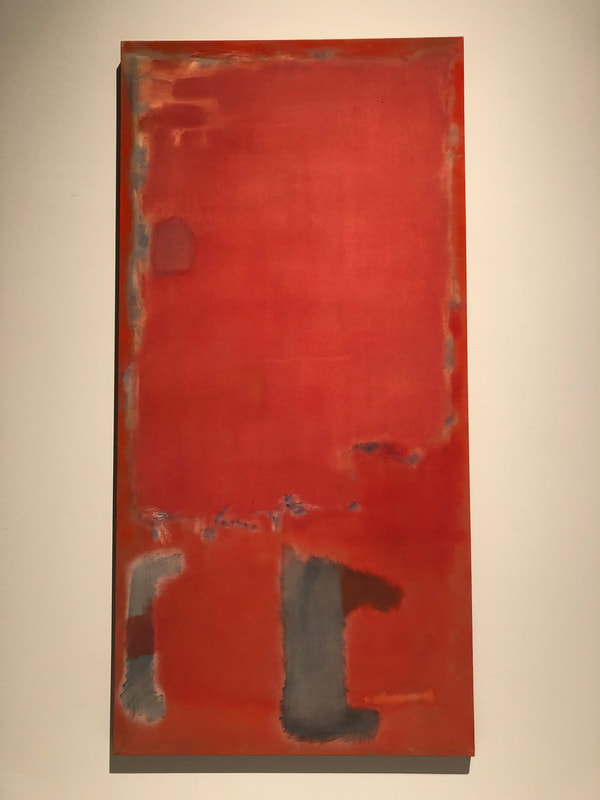

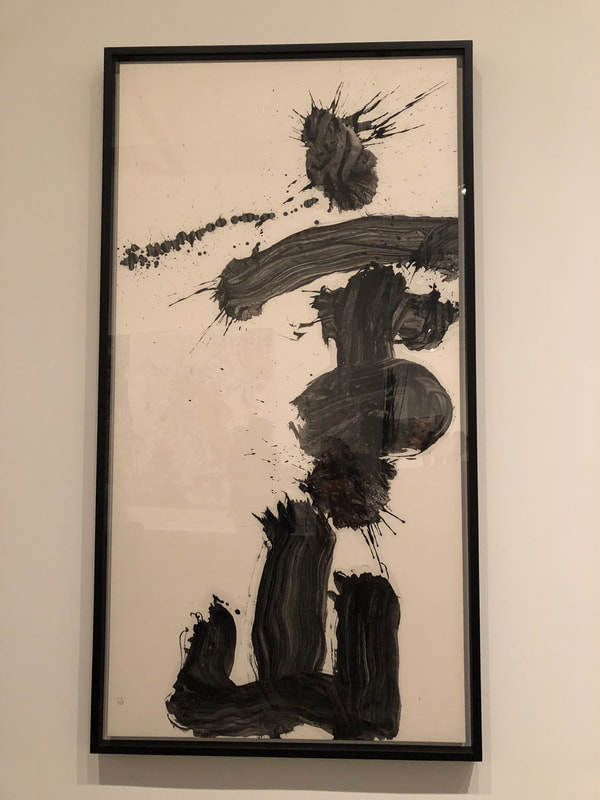

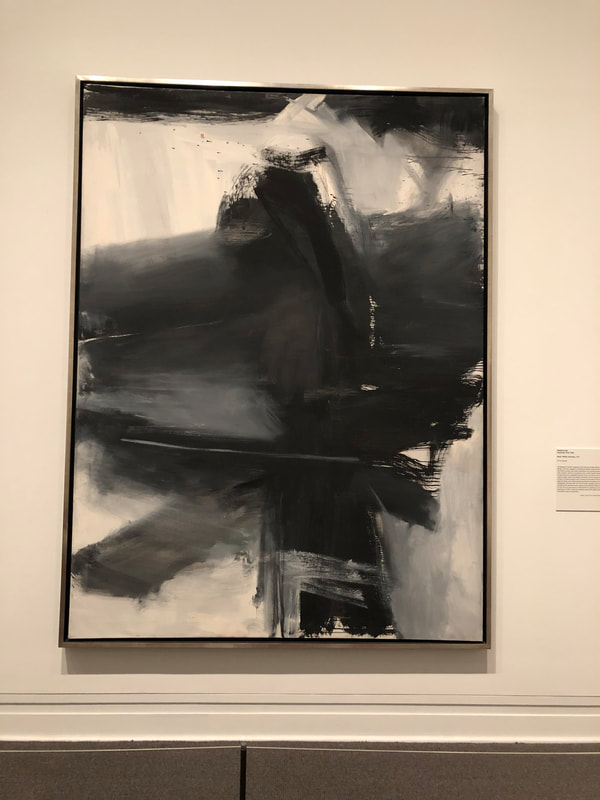

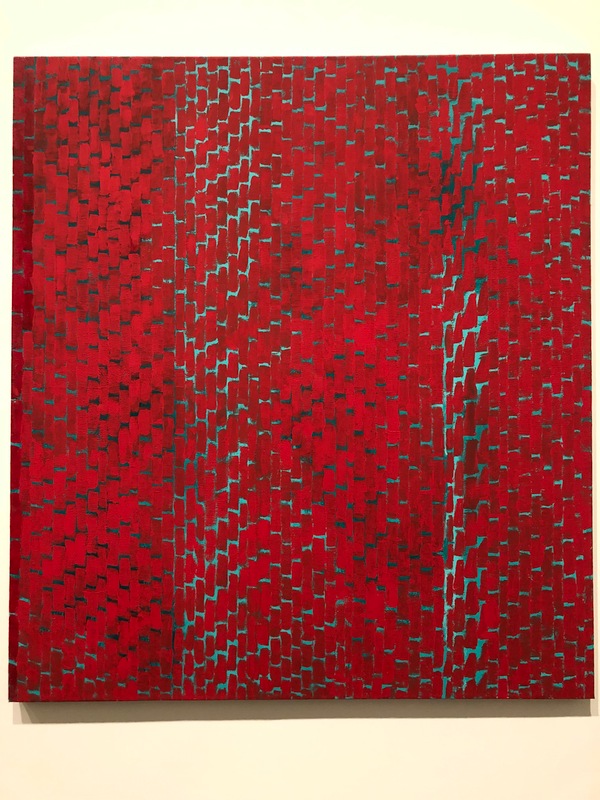

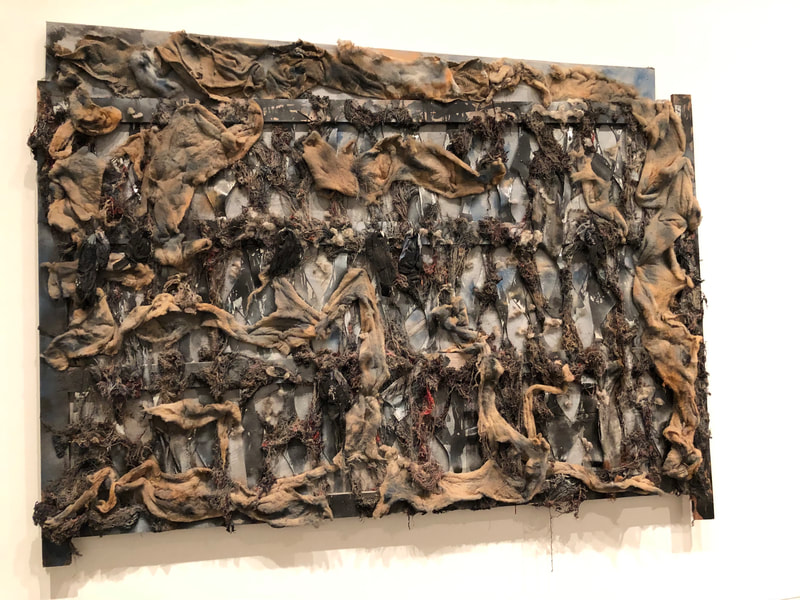

A month ago, as we were told to retreat from public life in NYC, I found people, including me, staying out more widely and gathering more, and more densely, than the warnings called for. Then slowly New Yorkers, including me, retreated to our neighborhoods and then to our homes. As we did this, as an individual I worried specifically about loved ones and more abstractly about the scale and effects of this impending cataclysm. My family and loved ones live on several continents, some of us alone. I live alone. Like many other people I’ve learned to increase my use of messaging, phone, and video for mutual care with family and friends. Some people living alone feel lonely. I have a very high tolerance, and even need, for solitude, so mostly I don’t feel lonely, but the current form of my solitude – distant, with no physical activity of care for others – is also a building block for my bubble. In contrast to my situation, some people and families, especially in the small apartments of my city, contend with the everyday struggles of being constantly closed-in and crowded in small spaces. I live in West Harlem in Manhattan. My neighbors are primarily Latino and African-American. My own coloring is just about halfway on the range you see in my community. I’ve lived here almost two years now. From the beginning I’ve loved that people commonly speak to me in Spanish, at least until they see my goat-in-headlights expression. Before COVID19 lots of social life in my neighborhood happened in public spaces. Groups of all ages, but especially older men, and sometimes older women, would gather on or around a few chairs on the wide sidewalks of Broadway or on the small patches of green in the neighborhood; or they would gather on and around the benches on the divider between the two sides of Broadway. It was common to hear music, usually with an African-American or Caribbean rhythm. Quite elderly people – some disabled – were given place and engaged with in these public spaces. This was not some idyllic world. Most people looked worn. Many looked busy. Some frowned. Many looked intent, even worried. But I noticed and loved how familiarity gathered among people who live and work here and slowly I started feeling allowed to join in that gathering of familiarity. I have never felt unsafe in my neighborhood, even returning home on foot or by bus or subway after midnight. As COVID19 became more clearly, more palpably, a threat, we were told to stay home except for essential services (health care workers, transit workers, EMT and FDNY, police, grocery store workers, pharmacy workers, postal workers, trash collectors, and so on) and essential activities (grocery and pharmacy shopping, exercise). At first my neighborhood seemed barely changed. The old men continued sitting in their chairs and chatting, the young men played basketball at the recreation park not far from my home. For the first few days the sidewalks did not look hugely different from pre-COVID19 days. Slowly that changed. People continue walking up and down my street, but fewer, with more distance, and increasingly with masks on. People go to laundromats, people need to get food, people need to get away from crowded homes, and people – essential workers – go to work. Over the last few weeks most of what I see is from my closed second-floor window (it’s still cold in NYC) or on my walks to the grocery store or post box, or to the river for fresh air, beauty, and also to be with people though we keep our distance. Last Saturday, a young man, a stranger, delivered our mail. Our usual mail carrier is a young African-American woman who was assigned this route (to her delight, she told me) about the same time I moved in. I started wondering why this man delivered the mail and when I saw her again a few days later on my way to the river, I exploded at her with relief (from a distance). She had taken the day off to be with her children and family. So what am I doing behind my closed window, apart from looking at my neighbors walking up and down my street and clapping at 7 pm? Lots of phone calls to people around the world who are concerned about me, and whom I’m concerned about. I speak to my mother in India every afternoon. Almost every day I have contact with each of my grown children who are making their own adjustments to living with COVID19. All my consulting work in conflict resolution and leadership development – in any case no longer my primary occupation – is on hold. My primary occupation is writing fiction. I am trying to get my first two novels published, and have been reading in what I considered my fallow time before I start my next novel. Often I veer off to read and watch the news, including NY Governor Cuomo’s press briefings. A few times a day I get mired in my Twitter feed. Mostly my engagement with news and Twitter is a kind of frantic spectatorship. I look for places to donate to and donate, both to organizations that will provide resources to those most hurt and political campaigns of people whose values I support. Because of my recent divorce, I have some money I can invest so I watch the stock market, somewhat bemused. A faint guilt permeates the time spent watching the stock market and remains under the surface. Then I tell myself, better me than those hedge funds and rich people. But the faint guilt remains. I rule out certain industries and companies. But the faint guilt remains. We are all complicit in the economy. Some have less choice. Some have less effect. Some gain. Some suffer a lot more. Some don’t care. The faint guilt remains. Starting a month or two before COVID19 affected me directly, I've noticed a storm gathering within me regarding my third novel. In the greater solitude of this stay-at-home time the storm signs have become more urgent and I’ve been trying to figure out whether it’s time to chase that storm, and, if so, where to get close to it, how to engage with it. It’s a very large storm that’s been gathering, about all of life, which means life all the way from the quivering inside from where we are subjects, objects, heroes of our destiny, and beaten down. I’ve loaded my jeep and I’ve started out to chase this storm. Meanwhile, in numerous phone calls and messages I’m asked, “How are you? How are you in NYC?” Friends and family worry about me and they see me as touching, directly, the frightening tragedy they read about in their news media and see on their televisions. Inarticulately I tell them, I’m in a bubble. I feel like I’m living in a bubble, I say. I feel like I’m living in a bubble in a location of immense fear and distress. That’s all I’ve been able to say. I haven’t been able to, I can’t, claim more than that. Concurrently my internal storm is getting larger and more compelling. I’m closer to it. I’m ready to start writing again. Then, in the last few days, two things struck my bubble. Not bursting it, mind you; this isn’t a heroic story. A friend who works with very low-income women and girls in Kolkata sent me The Guardian article called A Tale of Two New Yorks. Yup, I know this, there is no hiding was my external response. Yup, we can’t hide from this anymore was my internal response, with a distant cynicism about what we can hide from given a little time and self-serving distraction. I turned to follow my internal storm. The second thing was my experience at an open mic program organized a couple of evenings ago (April 10) by Under the Volcano, a superb international writing workshop program in Tepoztlan, Mexico which I had attended in 2018. When the announcement and invitation to sign up arrived in my inbox, I immediately responded and got a spot. In Tepoztlan, two years ago I did my first open mic reading; I chose an excerpt from my first novel, narrating the main character’s frenzied turning inside out while painting. At that time I was in the beginning stages of my second novel, so for April 10’s open mic I decided to read an excerpt from my second novel which is about memory, identity, and the internet. The novel is also about love, anger, and difference, but for my three-minute slot I chose a piece that is rollickingly about coding, gaming, hacking, and AI. I love that piece, I still do. But when I heard a young woman in the Bronx read her piece I hit my bubble. Inside, outside, all of me hit my bubble. In and after a texting exchange with another participant after the open mic program, I continued to bounce in and off my bubble. Then, yesterday, another friend sent me the same Guardian article referenced above. With the repetition and given my experience at the UTV open mic, just knowing that two New Yorks exist, already knowing, did not exhaust my internal or external response. I immediately wrote the paragraph below and sent it to the friend who’d just sent me the article and a few others. This is at the core of my bubble: “The public advocate pointed out that 79% of New York’s frontline workers – nurses, subway staff, sanitation workers, van drivers, grocery cashiers – are African American or Latino. While those city dwellers who have the luxury to do so are in lockdown in their homes, these communities have no choice but to put themselves in harm’s way every day.” I see that every day in my neighborhood. I know that my going out won’t help, in fact by increasing density will raise risk for everyone. So I stay home, doing work nonessential for my city in crisis, in many ways unconnected to my city in crisis, in some ways – if I gain from that benighted stock market – gaining, how can that be possible, gaining while my city is in crisis. The question is how do I connect my work, my living with this reality: how do I connect life inside me – that storm gathering – with life outside me? This blog post is one start to addressing that last question, amplifying the question, looking at how it rises both outside and inside me. I do not touch the distress of my city directly, but, in my bubble, I am part of it. This is not an ending. There is no resolution here. The inequities that exacerbated the unevenness of tragedy in my city existed before COVID19. The communities that have been asymmetrically affected by illness and death are likely also to be least helped by recovery efforts, least strengthened for the longer term. I can’t just be appalled. I can’t forget. This is a long game, not a short-term wringing of hands. Added perspective: This blog post focuses on my bubble in NYC where I live, but the bubble phenomenon is countrywide, worldwide. In the U.S., race and color add an enormous burden, but low-income people everywhere serve more and are served much, much less. Added comment: This was a difficult piece to write. It’s hard to reveal privilege even to myself, because a significant amount of privilege is unfair; I want to be “good.” But it’s much, much harder to live (and die! to see your loved ones die) without genuine equality of opportunity, equality of access to wellbeing, and equality of access to community resources in times of need. When I was young, I often fought for fairness, but I learnt slowly that life, often enough, is “unfair.” Getting old, I know life is “unfair,” but I’m learning that if I cut myself off from directly engaging with life outside me, I become emptier inside. In my case, directly engaging with life outside me means not turning away from being appalled by unfairness that I’ve always known; from my own confusions, complicities, and complexities; and from attentively, cannily choosing fairness and equity more and more rather than less. In practical terms, the last means supporting adequate wages and income security for minimum wage/hourly/casual/gig workers; easy access to health care information and services, including health insurance that is affordable or free where needed, but also specific systems in place for outreach, health education, and diagnostic and preventive services; attention to environmental health hazards, including housing deficiencies, work conditions, and inordinate production and marketing of junk foods; equality of opportunity in education which means explicitly lots more effort for children who don’t grow up with income-/class-based access and exposure outside of school systems. These are obvious ongoing things. Crises will come again; climate change is looming. In crises, the first question must be: what extra attention must we pay, what extra must we do to protect people with the fewest resources, in places with the fewest resources, who are often also most at risk? We must be prepared for this question, that extra. In a crisis we are all appalled. When this is over, how will I continue? How will you? I am coming to the end of my first artist residency. I’ve been revising my second novel, Pretty Lights, sometimes triumphantly, sometimes with a deep insecurity that it, my writing, will never be widely liked. I’ve also been drawing, at first as play, then increasingly with a seriousness that I have grown to cherish. And I’ve been walking a lot, on an average three miles a day. I had not known that a residency could be a space of such creative work and beauty. Four weeks ago, I flew into SFO and was driven here along with another artist, Beatrice Pediconi, a visual artist. On that drive she said two things that foresaw the shape and future of this residency for me. First, somewhat sternly, or perhaps she was just tired from our long and delayed flights from New York, she said that artists are here to work and don’t disturb each other. When she said this, it sounded almost monastic. I wasn’t intimidated, more curious. She also said that she does one residency a year. Now, I want to do the same. Another writer, an established author, had told me about residencies about five years ago. They were places of work and community she told me. She sent me her list, and Djerassi was on that list. At that time, with my other work and family life, a residency had seemed a complicating luxury. Then, after my first foray into a formal program for writers, Under the Volcano in Tepoztlan, Mexico in January 2018, I decided to apply to one residency. I was still living in San Diego and didn’t want to travel far. Djerassi looked beautiful and I loved that they mix artists of different kinds. Of course the chances of my getting selected were slim, though I didn’t know how slim until I got in. Soon after applying, my marriage started falling apart for reasons unrelated to the application, at least on the surface, though no doubt there were resonances from my writing into and out of the fault lines in my marriage. I got the forwarded hardcopy notification from Djerassi just a day or two before the deadline for responding, when I was already settled into my new life in New York City, that of a single woman claiming “writer of literary fiction” as her primary professional identity. The letter arrived like a soon-to-expire password to the new level of a quest, and I carried it like a child’s talisman, opening it on the subway and elsewhere for the rush of pleasure it gave me. So in the second week of September, I came to Djerassi, a few days before my younger child’s twenty-first birthday and my own almost-sixtieth birthday. I had just parted ways with the publisher who’d contracted to publish my first novel this fall. It was a late – and painful for me – parting that we mutually agreed on as it became increasingly clear that they wanted to publish a novel quite different from mine. Djerassi had been the first major acknowledgement of me as an artist. Now it remained the only major acknowledgement of me as an artist. But I came to Djerassi more confident of myself as a writer than I’d ever been and I’m leaving more confident of myself as an artist than I’ve ever been. My decision to withdraw my book from Speaking Tiger was remarkably without rancor. The decision was clear. I am not averse to further revision or editing, but I know now, quite profoundly, that I can only revise for a better version of my novel, not simply for a novel the publisher wants to publish. One day those will coincide for my work, but at this time Speaking Tiger and Night Heron are not a match. I came to the Artists’ House, the main house with old rooms, shared bathrooms, a lovely large kitchen, and views of forest, redwoods, ocean, dry grasslands, and variegated hills. The beauty starts off stunning as I drink my coffee on the deck in the morning, enwraps me through the day, especially on my long hikes, and closes with spectacular sunsets almost every evening. The few days we had a foggy cover come in from the ocean, the greens turned dull and a kind of gloaming settled on the day. I came to expect day after day of light, shadows, shapes, nature, and art. My last new walk – also beautiful, though the most ordinary, indeed the most dull – made me realize how addicted I’ve become to the quiver of sensory, intellectual, and emotional response to striking beauty. This addiction and its sources have run through my knowing and claiming every part of my creative work here – dreaming, writing, revising, drawing, experiencing shame, speaking about shame, researching my next residency, planning my next round of submissions, staring at the breeze – as work. Every one of us here worked. To my knowledge, every one of us worked every day, including over weekends. This was not vacation, nor was it a retreat from work. It wasn’t put-your-head-down-and-create-a-monetizable-product work, though all of us would want to earn from our art and for some of us art is the primary source of their income. It wasn’t work simply aimed at an externally demanded deliverable,* though all of us would want others to read, or see, or hear, or watch our work and feel some of what drives us to make it, perhaps remake it from their own history of being, perhaps think something new, jumping off a moment of the phenomenon of our work, and jumping into some wide mindscape of their own knowledge. Here at Djerassi more than ever, I deeply sensed, felt, and recognized how in the quivering process of creative work, art connects the deeply introspective – the interior and idiosyncratic space of living, being, sensing, feeling – with the world of historical time, of physical phenomena, of conventional forms and social understanding, and of the imprecise emotional lives of sentient beings who live together. The Djerassi program gave me almost constantly beautiful space and expansive time. Among other goodies, Chef Dan cooked us dinner every weekday evening, and our fridges, fruit baskets, and bread baskets were always full. My ten fellow artists – three visual artists, a composer, a choreographer, and five other writers, including a poet and a playwright – helped make this an intensely creative workspace for me, one of productive solitude as well as sometimes easy, sometimes intense interaction; artists at work as well as a community of artists. My fellow writers challenged me shockingly, shockingly productively. I am particularly grateful to the visual artists for letting me see some of what they see. And quite apart from the space and time it gave us, I am grateful to the program for inviting us to conceptualize an outdoor artwork (which I greedily assumed extended to me, a writer) as well as requesting from us an “artist’s page” as a small representation of the two-way gift between the program and each of us. These invitations led me first to conceptualize a Brutalist window – mimicking a window of The Met Breuer building – between the Djerassi junkyard and the forest beyond it, a reflection on the ineluctable immanence of two sides, indeed of a general integration. In this piece and three more that followed, I experimented with visually representing some passages of my writing. Emboldened by these efforts, I then experimented with creating a visual piece with no connection to my writing, indeed with no prior content intention at all. To me this piece is naïve art and delightful. Djerassi has been a place where I can work with intensity, seriousness, excess, and naivete. In many ways, my time at Djerassi was rather like falling in love for the first time. I close with deep thanks: to the Djerassi program for selecting me and placing me with this group of artists at this time; to my fellow artists for introducing me to new ways of thinking, feeling, seeing, hearing, grieving, and even laughing. I loved the mountain lion spirit that came into our group early, and then stayed with us. And, of course, many, and big thanks to all of you – artists and staff – for making my birthday this year one of the best ever! Below are some photographs of wild life and cattle who also charmed and shaped my life at Djerassi. And at the end are two videos that convey sounds of the wind when it blows. . * Some of the artists worked to deliver on commissions. (Spoiler alert re the movie Pasolini) The sequence of Nari Ward, Ishion Hutchinson, and Pasolini just happened; there was no plan on my part. Nari Ward and Ishion Hutchinson were paired by the New Museum. Not unexpectedly, they were a good pair, or rather I found Hutchinson’s response to Ward’s art provided something like a blended glass, part mirror, part filter. More about that in a bit. I added Pasolini because I wanted to use my Metrograph membership; I could walk to The Metrograph from The New Museum, and Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini was playing at the right time for me to move in this way through the city. Interestingly, going to Pasolini also became the right movement for a kind of intellectual and emotional trajectory. Though this is often the case as we knit the past into some kind of coherence, in this case I struggled with making the sequence coherent, then forced a coherence, and then was struck by what came of and from the forced coherence. I went to The New Museum for the first time about two weeks ago because a friend wanted to go there and I’ve wanted to go there for a long time. We started on the top floor with Jeffrey Gibson’s kaleidoscopic work and I passed through his work, loving the color and the immanence of movement. Later, I passed through Hélène Cixous’ odd, insightful, and romantic essay on Gibson’s work. “A dislocation is at work,” she wrote. Then we went down three floors of Ward’s large installations and smaller, more compact, art in the exhibition called “We the People.” The making of art from found objects is not new but the poignancy of this exhibition lay in the bend between the mourning of pain and history, and the fertility and beauty of, somehow, life. I had not heard of Nari Ward before this and got a little uncomfortable when I heard that he is a Harlem-based artist and his art connects directly to dispossession, not only of the past, but directly in the effects of gentrification in the present. I moved into West Harlem in June 2018, an innocuous, older-ing, and brown woman. I belong here, and I don’t. I had noticed, when checking out the museum before I went there with my friend, that Ishion Hutchinson was going to do a gallery talk on Nari Ward’s work. When I asked if there were still tickets available for that gallery talk, I was told there were. I was stunned. I guess this is NYC. I said, if you don’t think they’ll sell out while we, my friend and I, go through the exhibitions, I’ll wait to see Nari Ward’s work before buying a ticket for Hutchinson’s gallery talk. They assured me there would still be places, and there were, and once we’d walked through and down all the floors, I bought a ticket for the talk. So, on Thursday, May 16, my hair freshly colored, I went back to The New Museum, and waited for Ishion Hutchinson’s gallery talk. Ishion Hutchinson, like Nari Ward, is Jamaican-diaspora African-American. He is a poet I much admire. He took us, a group of about fifteen people, through parts of “We the People,” with eloquence, diffidence, clarity, and kindness. He took us – none of us belonging to the African diaspora, though all of us share fraught histories with Nari Ward and him – through touching what ‘fugitive’ can mean in history, selfhood and art; through hearing the grandness of aspiration while living in “material fetishes of failed utopias;” through sensing, distantly – in our case, each of us, perhaps with some guilt, or shame, or desire – “an old resilience which is part of [Hutchinson’s] heritage.” He told us about the abeng, and made its sound with his breath, his throat, and his mouth – this was a generosity of sound, not just a performance or lecture – and related it to the artwork called Savior. The abeng, he told us, makes the sound of the fugitive. He lost his voice briefly after making that sound. He stood in front of the two pieces called Breathing Panel and, at the end of his prose response to the artwork, repeated, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe….” In that brightly-lit gallery, with chattering, whistling sounds from an adjoining artwork, with only one other African-American, a gallery attendant, in view, with one other gallery attendant who looked Latino, and me, a class- (and caste-) privileged South Asian-American, with everyone else phenotypically white, mostly women across a range of ages, I wondered who couldn’t breathe now, why couldn’t they breathe. Who is breathing? For how long? Then he took us to the large, dark room in which Amazing Grace was installed; “a womb, a slave ship, an ark,” he called it at the beginning and towards the end. He walked us, two-by-two and holding hands, through the stroller-ship-womb. He read his poem Sprawl and repeated “my total reversal” – the last three lines of the poem – more than three times. And then we were done. And I got him to sign my copy of House of Lords and Commons which he not just signed, but also inscribed with “a small, drifting raft” for me. I walked out into the sunny afternoon, exchanged cheery words with one of the outside guards, walked through Chinatown, got a text message from my daughters in which they laughed at my ‘culture-vulture’ day, got to The Metrograph, and bought a ticket to see Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini. On Instagram, I posted some pictures and wrote: it’s hard to call walking through Nari Ward’s work at The New Museum a pleasure, but perhaps one can call it a tenderness, an amazement at how beauty can come alongside, and from, ugliness and sorrow while underlying cruelty and pain remain cruelty and pain. Pasolini starts, if not right away then very early on, with explicit, aggressive, unlovely sodomizing of two submissive young women. With Pasolini, I seemed far from the fugitive grief and anger and grace of Ward’s work and Hutchinson’s words. There was abject or abjectify-ing sex, followed by ordinary domesticity and interesting, but cold, words. “Narrative art is dead,” Pasolini told us, “we are in mourning.” “Mine is not a tale, it is a parable,” he said, “I am a form, the knowledge of which is an illusion.” To Pasolini, it appears, I, Meenakshi, am a moralist, who neither seizes the right to scandalize nor feels pleasure from being scandalized. About a third through the movie, I wrote in my running notes: so far there is very little that one might call kindness, or love, or tenderness. I watched more sex -- this time apparently not abject or abjectifying, more a kind of revolutionary procreation in a reversal of desire -- between beautiful people, with a raucous audience within the film, and us, a quiet audience outside the film, with our own arousals and withdrawals. Pasolini sees his work as a revolution. “I’m asking you to look around,” he says, “and see the tragedy… … starting with universal education … which leads us to want … and not stop short of murder…. … an appalling tradition that is based on this idea of possessing and destroying.” * The tenderness came at the end of the movie, when Pasolini is beaten to death on an industrial beach and the movie closes with a “clip” from a made-up movie based on Pasolini’s last work-in-progress. In the clip, Epifanio, an older-ing man, and his young companion are trying to get to Paradise and Epifanio can’t go on, so the young man says, “The end doesn’t exist. So we just wait. Something will happen.” Obvious shades of Godot, but owned here in its own terms, with its own peculiar pathos. In the end, the tenderness comes from the unabashed living of, and looking at, life with all its ugliness, its earthiness, its longings, its sensuousness, its beauty of form and light and shadow, its flaws, and just life. In general, I prefer to look at, sense, and join joy and tenderness of a different kind, but I did feel the tenderness at the end of this movie. Then started the struggle of knitting the coherence of my past. In my head, I stared at the obvious challenges of colonialism, racialism, the cruelty and survival of color lines of history, simplistically pitted against normative sexualization, scandalous desire, the intense ambivalence – intimacy and violence – of sex, and the cruelty and survival of power lines of history and didn’t get far, actually didn’t get anywhere, so retreated to higher abstractions. This is what I found. In Pasolini, there is no redemption, no desire for redemption. There is (only?) a wild grasping for freedom outside a cruel system that must be broken. In Pasolini, to the degree there is redemption, redemption lies in the external viewing of a complex tale – not a parable – about an ambitious fragility, or a fragile ambition. In Ward’s work and in Hutchinson’s words, there is redemption. Pain is overcome – indeed redeemed – by creation, by making beauty and life, and, in flashes, love and joy, from the remains of things, bodies, words, feelings, life itself. In Ward’s and Hutchinson’s work, perpetrators are on the other side; Ward’s and Hutchinson’s focus is on fugitiveness and resilience (Hutchinson’s words). In Pasolini, there is nothing fugitive, no one hides (except, perhaps, one time in the movie when Pasolini evades his interviewer’s question about what would remain if Pasolini could magically wave away everything he opposes), apparently nothing is hidden, perpetration is right there in front of you, drawing you in, people are broken down, perpetration itself is broken down. From this forced coherence, I knitted an easy/uneasy synthesis. In the face of suffering, sometimes one wants to shove perpetration up front and say, “fuck you, I don’t care!” Other times, one holds on to beauty, to the possibility of beauty; you want to cry because you cannot but care. And, zooming out, a creation that expresses only one of these impulses will feel flat – just brutal, or just sentimental. I did not find Ward’s, Hutchinson’s, or Ferrara’s work flat. To close, in my way: when I first decided to write about my forced coherence, I didn’t plan to include Jeffrey Gibson’s art and Hélène Cixous’ writing. But, having written thus far, I want to end with Gibson’s resplendent art. That is also life. And Cixous wrote of his dolls, which did not figure in this current New Museum exhibition, “… these were his people, his heritage, his self-portraits. Beautiful dreams, realized, and guarding their secrets.”

*Note: I wrote these words in my running notes. I’m pretty certain all the words and the logic they convey are accurate, but I’m not so sure about the ellipses. My bad child practice is as follows: when I notice a feeling of shame or awkwardness, because something I did wasn’t “right,” I take a moment to stop, pay attention to that feeling fully, get as aware as possible of the feeling and what I think generated it, then I tell myself, and this is very important, “it’s OK, I’m just a bad child.” I find this releases myself and others. Below is a longer explanation of this practice and its effects.

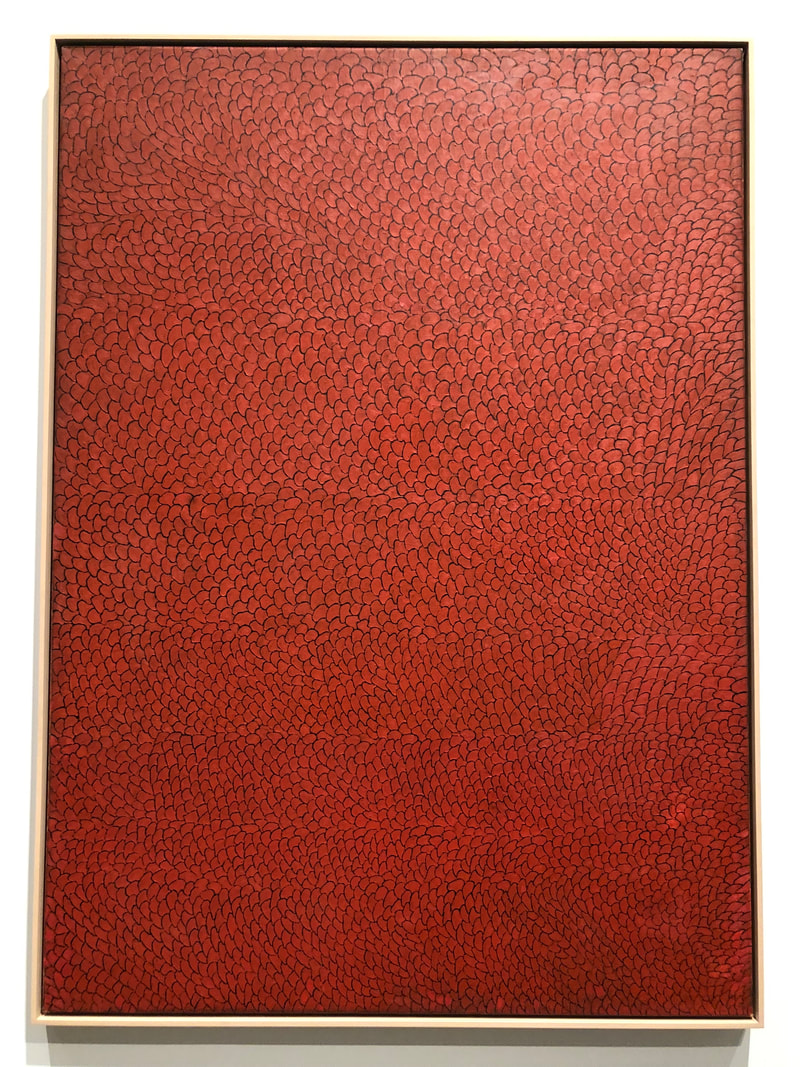

In the introspective work I have been doing over the last few months, I have been focusing particularly on expressions or evidence of “shadow,” most simply areas or times of discomfort, when I feel a rush of hurt or shame and am inclined to blame someone or something outside myself or put myself down. “Shadow” shows up and may be discovered through any number of other feelings (including positive feelings), but my spectrum of hurt and shame is most pernicious and appears to be a large tip of my shadow iceberg. A few weeks ago, I started to notice, and dwell in, my hurt and shame whenever I felt them in small ways that normally I would do nothing about; typically such small twinges of hurt and shame got internally absorbed or accommodated. I would cover over the little hurt or shame and move on. The bad child practice came about because I started noticing my own accumulation of absorbed or accommodated hurt and shame. I started noticing each feather of hurt and shame as it was added. The feather metaphor comes from something quoted by a woman scientist in a recent NYT article about the Salk Institute: “A ton of feathers still weighs a ton.” I also noticed, by observation and being told, that others had similar “feathers” of hurt and shame, for which, in most cases, I felt relatively easily compassionate. From my history, I know I have a thing about being a bad child. I think most people do. As all these reflections pottered around in my mind, the bad child practice emerged. I firmly decided that every time I felt a feather of hurt or shame, I would look at it, be as conscious of the feeling as I could be and then let go of the part in which I put myself down; and told myself, “it’s ok, I’m just a bad child.” It’s allowing myself to be flawed, without self-indulgence, avoidance, or accommodation. This practice is similar to what a friend and others have called “self-compassion,” and, most crucially, it connects my condition of “bad child” with bad child in every other person. For me, the bad child practice only works if I consciously, attentively, and kindly join compassion for others with compassion for myself, in both directions. In other words, it is a simultaneous release for myself and others to be flawed, to have shadow. This is not covering over or condoning. Indeed, there may be need to avoid, very consciously, denial, or accommodation of self or others. There may be need to speak, inquire, listen, act, and engage for “justice,” for acknowledgement, for reparation, and for forgiveness – in relation to myself, or someone else, or both, or many. I look at such cases closely. Always, I can’t resolve them, at least not right away or completely, but I add what I learn from this attention to the knowledge and questions that my purposeful “good child” will use when it’s time again for her to reflect and act. What I mean by forgiveness has also evolved, and, recently, I realized it is not a simple release of the origin of hurt and the hurt itself. It is not letting go in a simple way. The hurt does not go away. If small, it may be forgotten. But if something brings the memory back, even if unconsciously in the senses and the body, the hurt is still there and there may be a harking back to which another person may say, “how long will you carry that? When will you get over it?” In turn, such a response may lead to a rehashing of the original infraction with all the defensiveness and judgments that such hashing involves. However, in many cases, what is needed is attention to what is present that is bringing back the memory in one’s body and feeling. With this understanding of hurt, forgiveness means a two-fold layering. First, it requires a mutual acknowledgement that the hurt doesn’t go away. Once there is hurt it is always in your body.* The “mutual” may involve another person, or people, or be wholly within yourself. The second layer of forgiveness, folded over, is fully uncovering and making explicit that what one feels for the other person, or oneself, or the world, or some combination of these is so much more than the hurt. In the simplest terms of forgiving another person, this means saying, “the hurt will never go away but my relationship with you is so much more than that hurt. Who you are for me is so much more than that hurt.” I acknowledge that there are hurts so grievous that there may be very little, or even nothing else, in relation to the person or people who committed the acts that hurt. In such situations, the forgiveness, when one can get there, is inside oneself, and also in relation to the world: “I am so much more than that hurt. And (if one can get there) the world has and gives so much more than that hurt.” Circling back to my “bad child practice,” it is a form of forgiveness for oneself and others. The bad child part of me will never go away, and I am so much more than the bad child part of me. The bad child practice is not a license to harm others. It is a practice to engage and get beyond hurt and shame. So what happens if my hurt and/or shame issue from an interaction that is deeply hurtful, harmful, unfair, or destructive? In my bad child practice, when I look closely and with full awareness at my feelings of discomfort in small instances, it builds a practice and capacity I use in larger and more significant instances, to notice and sit with the effects on myself and on others. If these effects include harm or potential harm, the next step is not the bad child practice of “it’s ok, I’m just a bad child,” but a conscious effort to avoid the most common traps of covering over (denial or avoidance), or accommodation (silencing oneself or putting oneself down), or attack/defensiveness (you are as much or more at fault, as bad or worse than me!); and, instead of these, to engage in honest, flawed, vulnerable, and courageous ways with oneself and any others involved. I don’t always make this effort; it’s exhausting and I fear anger and judgment in response to engagement I might initiate. I can’t resolve everything, I tell myself. Sometimes that is a reasonable decision, but I also risk slipping into an insidious practice of accommodation – of myself or of others or both. That’s a topic for another piece. If you want to try out my bad child practice, here’s a caution. As with any practice, the bad child practice can decline into a narrowing habit rather than an opening into new and deeper awareness and reflection, so I would try it for a short period (two weeks?), see what you learn from it, and check once in a while that it isn’t becoming a crutch. At its best, my bad child practice has made me a kinder and more courageous (risk-taking!) person who is more patient with both joy and pain, and even with boredom and waiting. * And there is also multi-generational transmission, a topic too large and complex for this small piece, but definitely worth adding to one’s deepening attention, awareness, and reflections. Acknowledgement: As with anything I write and any knowledge I have, the sources are out in the world as much as in me. Usually, this does not need to be said. For this piece, I want to explicitly acknowledge that it draws on what I have learned over years of engaging with the wisdom of colleagues (Public Conversations Project, University of San Diego, RISE San Diego, and others), friends (my wise and loving friends in San Diego and elsewhere in the world), family (my mother, my daughters, and others), and knowledge traditions (academic, story-telling, Tibetan Buddhism, Zen Buddhism, psychotherapy, and others). What I’ve written here comes from how all of these sources have helped me understand – an ongoing process – myself and my world. If you see your knowledge in here, it probably is your knowledge in here. Thank you. The title of Zora Neale Hurston’s most famous book comes from the sentence: “They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” This is an extraordinary sentence in a book full of extraordinary sentences. I read the book weeks after walking, for the first time, through the Epic Abstraction exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In that first encounter with Epic Abstraction, I was astonishingly moved. I don’t cry in public, usually, so I didn’t cry, but I’m sure my eyes looked bulbous and unusually filmed, for that was how they felt. My breathing was thrown off by some of the pieces; I felt a wonder, and a recognition. I felt emotional in a way that was both full and hollow. I wouldn’t have been able to say, with any truth, what it was about any of those paintings that made me feel this way. If you insisted, I’d have made up something which may have sounded eloquent, even profound, or may have stumbled out in some convoluted fashion. I had never before had this kind of first degree emotional response to art in a museum or gallery, and certainly never to abstract art. Of course, this had everything to do with me: who I was standing in those galleries, who I am today. But whatever the sources of this response, the effect was a completely new understanding of this art. Until this particular viewing of this particular exhibition, I’ve appreciated abstract art for its innovations in form, its deconstructions of the figurative, its intellectual conundrums, its challenge to knowledge and certainty, and its invitations to sense and know in new ways. But all of this was cognitive; if emotion arose at all it came from a secondary process of narrative meaning-making. This particular, January 2019, encounter with epic abstraction – mostly very, very large and very, very abstract pieces of art* -- was different in that these pieces simply in their size, form, color, and juxtaposition evoked a great helplessness and tearfulness. These words look silly and excessive, but my feelings at that time way exceeded these words. Which brings me back to Zora Neale Hurston’s sentence about eyes watching God. “They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” In my reading of this sentence, it’s not about faith in God, though the people she was writing about may well have been God-fearing. The sentence gets its power from bearing narrative witness to a moment of extraordinary humanness – only being able to live, only pressing to live, with all of its terror, helplessness, grandeur, consciousness, God. This was nothing so limited as “staring at the dark.” This was emotion, longing, life (and death) beyond words and cognition, but not reduced to animal instinct. Hurston has an animal figure – a dog – in the same hurricane-driven floods as her narrator, Janie, and the other people in “the muck.” The dog’s eyes were crazed, phenomenally “staring at the dark,” staring wildly at anything it could see, desperate to live through aggression. It turns out the dog was rabid. Even if Hurston hadn’t needed the madness for a narrative twist, I don’t think she would have said its eyes were watching God. I returned to the Epic Abstraction show a couple of weeks ago, eager to repeat and record my emotional experience of the first time. In the beginning, I thought too much. Feel, I told myself. That didn’t work. Then I just let myself write in response to pieces, and feeling returned, filtered through words, thinner, a trace, but there. Though I was not in a hurricane during that first visit to Epic Abstraction, and I was not – in a very real, palpable way – on the verge of dying, in retrospect I appropriated Hurston’s metaphor to understand my experience that first time. That first time, my eyes peeped through the art at God. That art, that day, expressed humanness beyond words and cognition, the fullness of human desire to live, experienced and expressed with the sensate and cognitive sensibilities of our complex bodies. We are not machines. One day an artificially intelligent entity may mimic, with great sophistication and nimbleness, every human function, but if it is cut off from corporeal humanness, it will only be able to formulate helplessness; it will not feel the helplessness of “eyes watching God.” What does all of this have to do with moral authority? For a long time I have been struck by the moral clarity and power of the writings – including fiction, non-fiction, and speeches – of people who’ve survived sharp and sustained exploitation by other groups of people.** More recently, I’ve had opportunities to work with people who’ve lived through histories and direct experience of sharp and sustained pain. I’ve had such opportunities before and I’ve risen to them well – thoughtfully, kindly, in facilitator-speak holding space for them to be themselves through the hard transitions of survival and being that they were living. But I was different in my recent, deep and lengthy, opportunity. I had my own experience of sharp and sustained pain. It was urgent enough that I couldn’t simply dismiss it as small relative to the pain of others, to the histories of grinding indignity and uncertainty that many others live with. Rationally I know my situation is not bad; of course I’m not teetering on the edge of physical or emotional survival. But, emotionally, I’ve had to contend with very real helplessness, and, in the work I had to do with colleagues in San Diego, I was inexorably pulled to feel it, express it, and connect it to the helplessness of others. In this work, my understanding of moral authority deepened. A few days ago, I grandiloquently told a group that I am currently deeply interested in how desire and emotion – especially love, fear, and shame – are foundational elements of moral authority. What is moral authority? one of them asked. Here is my answer, today: moral authority is the agency with which you relate to others, through words, actions, metaphors, images. It is essentially social, both contained by and spilling out of convention. In Buberian terms, it is the action of “I” in relation to “you.” In Biblical terms, in part via Jean-Paul Lederach, it is seeing the face of God, or not, in others. It is the living of desire and helplessness, mediated by socio-economic and political structures, shaped by linguistic possibilities and the grace or awkwardness of particular bodies at particular times, and expressed, consciously and unconsciously, in every act of living. Mostly, moral authority is expressed and heard as dogma or debatable logic – sometimes self-focused and self-serving, sometimes prosaic and parochial, sometimes ineffably greater-than and universal. In my view, moral authority gains an enormous power and tenderness when it draws on the lived tension between desire and helplessness, mediated by emotions that may be described as love, fear, shame, joy, anger, pain, and awe. Everyone experiences that spectrum of emotions. In my experience, those who are more aware of that spectrum in themselves have more clarity and kindness of purpose, whether within and in relation to the smallest units of dyads or families or to the largest of collectives and, even, to humanity and life in general. The Epic Abstraction exhibition surprised me by evoking my own helplessness at losing, and letting go of, my partner of twenty-eight years. Zora Neale Hurston gave me a metaphor for that helplessness. I’m still figuring out how that helplessness, and its attendant emotions, are shaping and will shape my actions in relation to others. Certainly, it’s already made me much more intensely aware of love in my life, love that I give and love that I get. It mostly makes me a kinder – some would say “softer”, lol – thinker (though a recent exchange makes me think that I am softer in some ways but clearer and firmer in others). It’s influencing questions and dilemmas in my fiction. I don’t yet know how the effects will show up in my political activity. We’ll see. A new Presidential election is coming up. The last election made me angry and hurt. It didn’t quite reduce me to helplessness, but I do feel fear and uncertainty and those, along with the thread of helplessness in my personal life, are shaping, will shape, the moral authority that drives my purposes and actions. * Notes on the structure and pieces, along with some photographs, are appended below. ** Parenthetically, I’ve also been struck by how slowly and in very limited ways such writings have been acknowledged, read, engaged, and drawn on by dominant groups. Raw notes on, and pictures of, the exhibition, first from my second visit, and then some memories from my first visit Coming up to the Epic Abstraction show from the southern end, I pass Kiki Smith’s Lilith, to me fearful and vigilant, sort of at the other end of desire and moral authority from Janie in Their Eyes Were Watching God. If you think of this spectrum as circular rather than a straight line with infinitely divergent ends, this end is the same as the beginning. To my eyes, Lilith looks like a precursor to Mystique in X-Men. A group of Euro-American people – two women and one man – just stopped to look at Lilith. Two of them are brightly, innocently, fascinated, especially by her eyes. The third, a woman, walks away saying, “It’s too scary, I don’t like it.” The first piece of art on my right as I entered the Epic Abstraction exhibition is New York #2 by Hedda Sterne. It’s equally divided between light and dark. Her signature is on the left, in the middle of the vertical plane. My eye is drawn to the dark, the tunnel, the sewer. My mind is working too hard to see and interpret form to allow attention to feeling. Next comes Cy Twombly’s Dutch Interior, which gives me the pleasure and permission of utter foolishness, at scale. “I don’t know what to do.” The artist is present in the action. Time passing. The space covered, not covered, done. Jackson Pollock’s November 28, 1950. Museum clickbait. Overseen. Too confident. Is it his ego I resist? Is it my ego that resists? Moving on. Clyfford Still’s 1950-E. I’m comforted by the burgundy at the bottom. It feels right, balanced, the burgundy, left bottom; blue, right top-ish. Much more black than white, as much grey as black. A comforting painting. The last painting in this first space I entered from the Lilith stair is Conflict (1956-57) by Alfonso Ossorio. My eyes were drawn to this piece when I entered – it’s opposite Sterne’s New York– but I left it until last. It makes me feel alive: the red heart, the three-dimensional explosiveness, with textured paint of varying thickness. The color palate is human – blood, shit, skin, bone. In the middle, more or less, of this first space is Barbara Hepworth’s Single Form (Eikon) (1937-38). I ignored this sculpture the first time I walked through this show, sort of dismissed it. What was that about? It’s too classic, too phallic, too heavy, too large, too squarely confident, too masculine, derivative. The sculpture feels like my past, unlike Lilith and Booker’s Raw Attraction (coming up). But when I force myself to look at it more closely, I’m moved by the wings of the pillar as it expands up a little, by the trickles or ripples down the sides of the square block pedestal, including on the broken corner of the block. Most of the paintings in the Pollock and Rothko rooms slip past me in their familiarity. Kazuo Shiraga’s red and black untitled (1958) is in the Pollock room, right near the entrance to the exhibition from that end. I like it a lot. In the Rothko room, his No. 21 (1949) stands out. It feels uncertain, fading. I expected it to be a significantly early or late painting, but it is dated right in the middle of his painting life. The other piece of art in the Rothko room that stands out to me is Isamu Noguchi’s Kouros, a very large sculpture made of pink Georgian marble. Kouros is a youth, male. This sculpture is not a young man. Or maybe it is. It’s smooth, confident, supple, large, and fragile. The room that really drew my imagination on this visit is the one dominated by Chakaia Booker’s poky, horny, piping, leaking vagina (Raw Attraction) in the corner of the room, flanked on the right by another very large painting (untitled, 1960) by Clyfford Still, this time red is the dominant color, not as comforting as 1950-E (which, by the way, looks ominous from this seat in front of untitled 1960; the black and grey merge from this angle). Still leaves a few light striations, almost drips in the black and in the red. One of these is in the black, right in the center, in the bottom half of the painting. It looks forgotten, a flaw he deliberately forgot. On the left flank of Raw Attraction is Mark Bradford’s Duck Walk (2016). Wow, what a fantastic painting, mixed media. It makes me come alive. The left panel is mostly white with yellow-mustard in the middle, the right panel is black in the middle, yellow swirling out. I see anime faces in the left panel. I like that there is no red in the painting. The color palette is spare. White, black, yellow, and some beige. [Comment added while typing these notes in: His name had sounded familiar, but I only now remembered why. He recently added What Hath God Wrought to the Stuart Collection of remarkable outdoor art at UCSD.] Completing this space are two of my favorite paintings in this show, in large part because they are side by side: Inoue Yūichi’s Kanzan (Cold Mountain, 1966) with stylized renditions of the characters for cold and for mountain and Franz Kline’s Black, White, and Gray, 1959. Almost ending the making of this space is Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 70, 1961. The emotional impact of these artworks in this made space is as much due to the curation, the placement of a work in the space and relative to other pieces, as to each separate artwork itself. And then there is the fabulous, hermetic, almost 21st century video game image – Judit Reigl’s Guano (Menhir), 1959-64, a layered painting: like history, like death, like a reproduction of fallowness – that transitions me into the extraordinary female-human-20th century space dominated by Louise Nevelson’s Mrs. N.’s Palace, 1964-77. -----End of direct notes --- The second trip, of necessity, because of a phone call I was committed to making, ended there. I don’t have notes from the first trip, all I have are memories that are now thoughts in the present. I remember loving the unapologetic size, steadfast standing in place, and geometrical complexity in monochrome grey of Mrs. N.’s Palace, surrounded by sharp-edged images created by men, and also rounded, even sentimental, images created by women. Reds drew me on that first trip as well. I gazed at Alma Thomas’s Red Roses Sonata (1972) and Elizabeth Murray’s Terrifying Terrain (1989-90), and felt the threat and harmony of each. I shied away from, then stared at, Thornton Dial’s Shadows of the Field (2008); now it looks ominously like a faded, tattered flag, millennia before a fossil, though this soft tissue of history and affect is lived in consciousness or disappears. The color palette of Frank Bowling’s Night Journey (1969-70), the yellow falling through the horizontal center, held me, though I found the continents distracting in how they historicized color and shape. Finally, the exhibition ended (or began, if you came in that way) with Yayoi Kusama’s No. B. 62 (1962): mostly evenly red shells or scales, in retrospect a carapace, perhaps the curved surface of that odd creature, a pangolin, laid out in two dimensions. Postscript: I was hesitant to post this piece, even after proofreading it and uploading the photos. This morning, a beautiful, sunny spring day in NYC, I had to make explicit the life and joy I also see in and through the helplessness and moral authority. If you live, you fall in love with life again (thank you, Andrea, for your Facebook cover picture), even if only in small ways, and in that falling in love, you claim life for yourself, and often claim it for others as well. Janie (and Zora Neale Hurston) did that, the Epic Abstraction artists did that. Reading Hurston, and walking through the exhibition, and looking at the sunlight today, I am doing that.