|

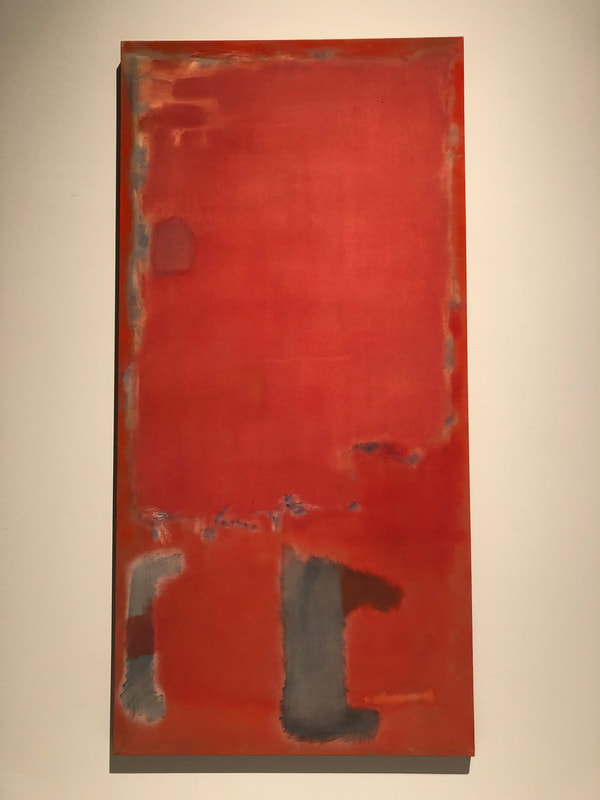

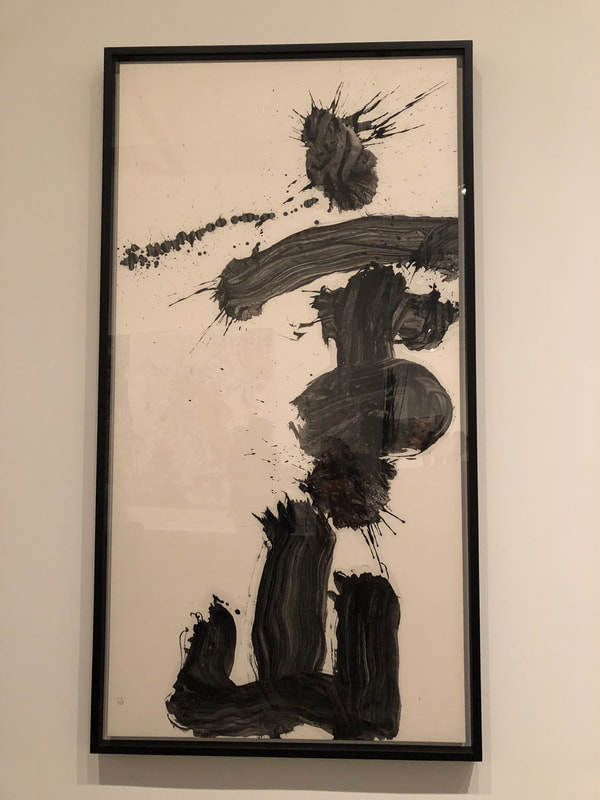

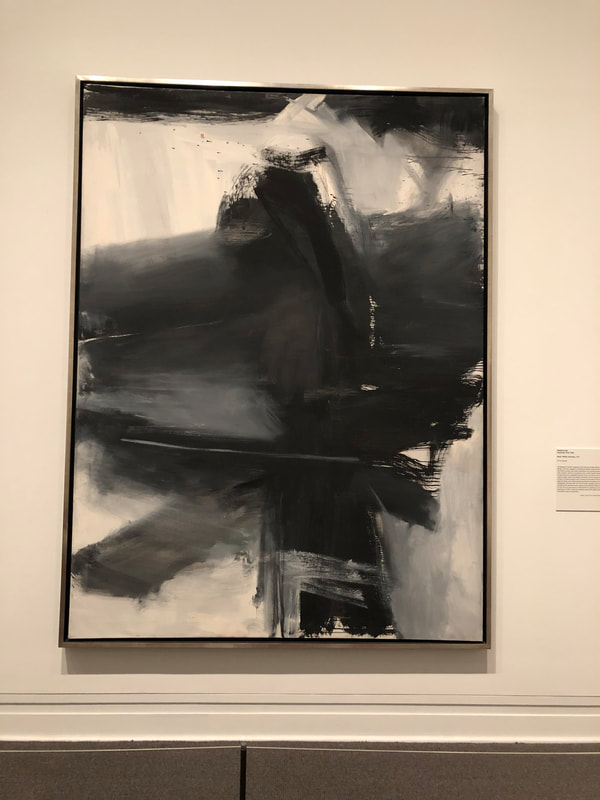

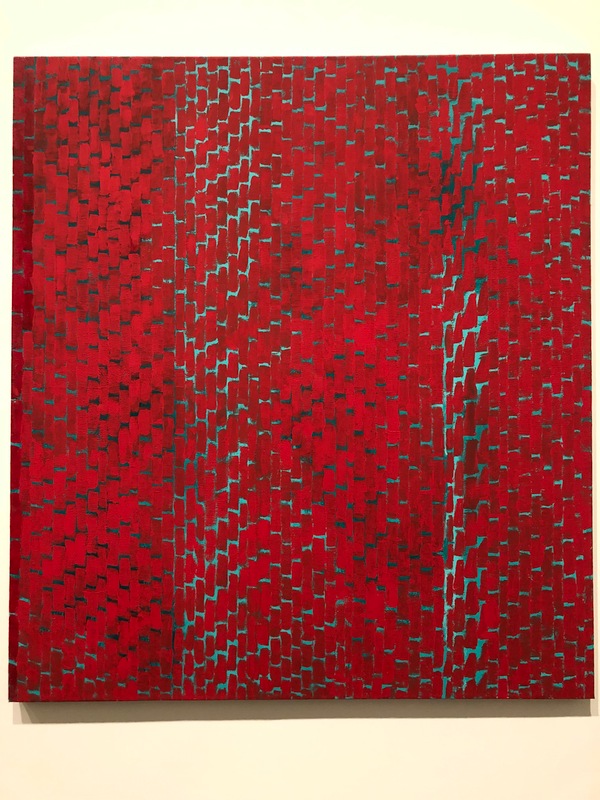

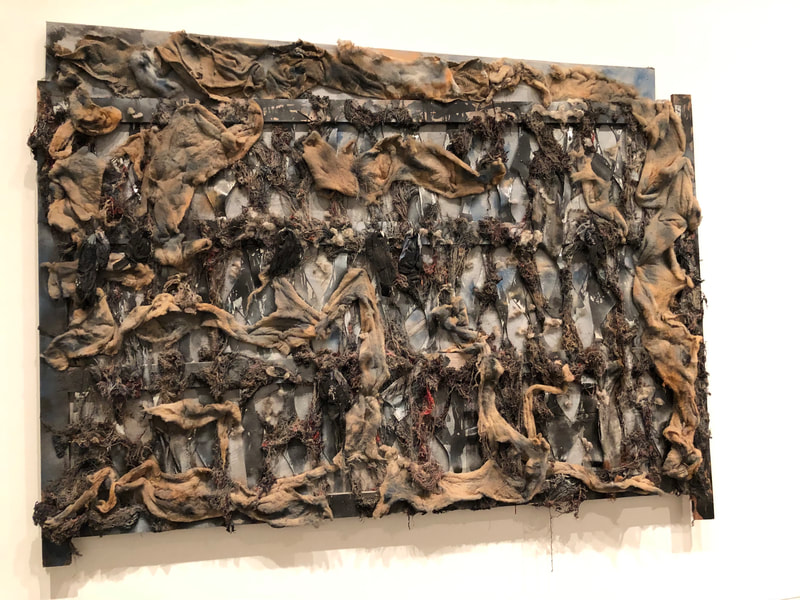

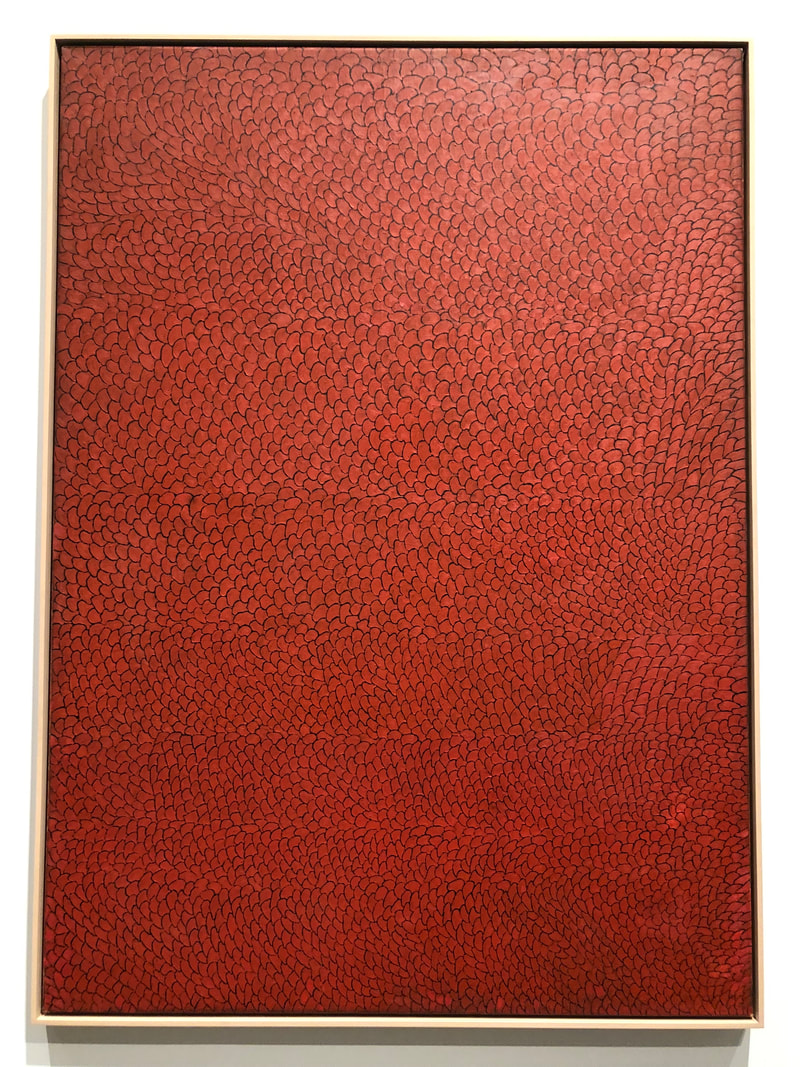

The title of Zora Neale Hurston’s most famous book comes from the sentence: “They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” This is an extraordinary sentence in a book full of extraordinary sentences. I read the book weeks after walking, for the first time, through the Epic Abstraction exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In that first encounter with Epic Abstraction, I was astonishingly moved. I don’t cry in public, usually, so I didn’t cry, but I’m sure my eyes looked bulbous and unusually filmed, for that was how they felt. My breathing was thrown off by some of the pieces; I felt a wonder, and a recognition. I felt emotional in a way that was both full and hollow. I wouldn’t have been able to say, with any truth, what it was about any of those paintings that made me feel this way. If you insisted, I’d have made up something which may have sounded eloquent, even profound, or may have stumbled out in some convoluted fashion. I had never before had this kind of first degree emotional response to art in a museum or gallery, and certainly never to abstract art. Of course, this had everything to do with me: who I was standing in those galleries, who I am today. But whatever the sources of this response, the effect was a completely new understanding of this art. Until this particular viewing of this particular exhibition, I’ve appreciated abstract art for its innovations in form, its deconstructions of the figurative, its intellectual conundrums, its challenge to knowledge and certainty, and its invitations to sense and know in new ways. But all of this was cognitive; if emotion arose at all it came from a secondary process of narrative meaning-making. This particular, January 2019, encounter with epic abstraction – mostly very, very large and very, very abstract pieces of art* -- was different in that these pieces simply in their size, form, color, and juxtaposition evoked a great helplessness and tearfulness. These words look silly and excessive, but my feelings at that time way exceeded these words. Which brings me back to Zora Neale Hurston’s sentence about eyes watching God. “They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” In my reading of this sentence, it’s not about faith in God, though the people she was writing about may well have been God-fearing. The sentence gets its power from bearing narrative witness to a moment of extraordinary humanness – only being able to live, only pressing to live, with all of its terror, helplessness, grandeur, consciousness, God. This was nothing so limited as “staring at the dark.” This was emotion, longing, life (and death) beyond words and cognition, but not reduced to animal instinct. Hurston has an animal figure – a dog – in the same hurricane-driven floods as her narrator, Janie, and the other people in “the muck.” The dog’s eyes were crazed, phenomenally “staring at the dark,” staring wildly at anything it could see, desperate to live through aggression. It turns out the dog was rabid. Even if Hurston hadn’t needed the madness for a narrative twist, I don’t think she would have said its eyes were watching God. I returned to the Epic Abstraction show a couple of weeks ago, eager to repeat and record my emotional experience of the first time. In the beginning, I thought too much. Feel, I told myself. That didn’t work. Then I just let myself write in response to pieces, and feeling returned, filtered through words, thinner, a trace, but there. Though I was not in a hurricane during that first visit to Epic Abstraction, and I was not – in a very real, palpable way – on the verge of dying, in retrospect I appropriated Hurston’s metaphor to understand my experience that first time. That first time, my eyes peeped through the art at God. That art, that day, expressed humanness beyond words and cognition, the fullness of human desire to live, experienced and expressed with the sensate and cognitive sensibilities of our complex bodies. We are not machines. One day an artificially intelligent entity may mimic, with great sophistication and nimbleness, every human function, but if it is cut off from corporeal humanness, it will only be able to formulate helplessness; it will not feel the helplessness of “eyes watching God.” What does all of this have to do with moral authority? For a long time I have been struck by the moral clarity and power of the writings – including fiction, non-fiction, and speeches – of people who’ve survived sharp and sustained exploitation by other groups of people.** More recently, I’ve had opportunities to work with people who’ve lived through histories and direct experience of sharp and sustained pain. I’ve had such opportunities before and I’ve risen to them well – thoughtfully, kindly, in facilitator-speak holding space for them to be themselves through the hard transitions of survival and being that they were living. But I was different in my recent, deep and lengthy, opportunity. I had my own experience of sharp and sustained pain. It was urgent enough that I couldn’t simply dismiss it as small relative to the pain of others, to the histories of grinding indignity and uncertainty that many others live with. Rationally I know my situation is not bad; of course I’m not teetering on the edge of physical or emotional survival. But, emotionally, I’ve had to contend with very real helplessness, and, in the work I had to do with colleagues in San Diego, I was inexorably pulled to feel it, express it, and connect it to the helplessness of others. In this work, my understanding of moral authority deepened. A few days ago, I grandiloquently told a group that I am currently deeply interested in how desire and emotion – especially love, fear, and shame – are foundational elements of moral authority. What is moral authority? one of them asked. Here is my answer, today: moral authority is the agency with which you relate to others, through words, actions, metaphors, images. It is essentially social, both contained by and spilling out of convention. In Buberian terms, it is the action of “I” in relation to “you.” In Biblical terms, in part via Jean-Paul Lederach, it is seeing the face of God, or not, in others. It is the living of desire and helplessness, mediated by socio-economic and political structures, shaped by linguistic possibilities and the grace or awkwardness of particular bodies at particular times, and expressed, consciously and unconsciously, in every act of living. Mostly, moral authority is expressed and heard as dogma or debatable logic – sometimes self-focused and self-serving, sometimes prosaic and parochial, sometimes ineffably greater-than and universal. In my view, moral authority gains an enormous power and tenderness when it draws on the lived tension between desire and helplessness, mediated by emotions that may be described as love, fear, shame, joy, anger, pain, and awe. Everyone experiences that spectrum of emotions. In my experience, those who are more aware of that spectrum in themselves have more clarity and kindness of purpose, whether within and in relation to the smallest units of dyads or families or to the largest of collectives and, even, to humanity and life in general. The Epic Abstraction exhibition surprised me by evoking my own helplessness at losing, and letting go of, my partner of twenty-eight years. Zora Neale Hurston gave me a metaphor for that helplessness. I’m still figuring out how that helplessness, and its attendant emotions, are shaping and will shape my actions in relation to others. Certainly, it’s already made me much more intensely aware of love in my life, love that I give and love that I get. It mostly makes me a kinder – some would say “softer”, lol – thinker (though a recent exchange makes me think that I am softer in some ways but clearer and firmer in others). It’s influencing questions and dilemmas in my fiction. I don’t yet know how the effects will show up in my political activity. We’ll see. A new Presidential election is coming up. The last election made me angry and hurt. It didn’t quite reduce me to helplessness, but I do feel fear and uncertainty and those, along with the thread of helplessness in my personal life, are shaping, will shape, the moral authority that drives my purposes and actions. * Notes on the structure and pieces, along with some photographs, are appended below. ** Parenthetically, I’ve also been struck by how slowly and in very limited ways such writings have been acknowledged, read, engaged, and drawn on by dominant groups. Raw notes on, and pictures of, the exhibition, first from my second visit, and then some memories from my first visit Coming up to the Epic Abstraction show from the southern end, I pass Kiki Smith’s Lilith, to me fearful and vigilant, sort of at the other end of desire and moral authority from Janie in Their Eyes Were Watching God. If you think of this spectrum as circular rather than a straight line with infinitely divergent ends, this end is the same as the beginning. To my eyes, Lilith looks like a precursor to Mystique in X-Men. A group of Euro-American people – two women and one man – just stopped to look at Lilith. Two of them are brightly, innocently, fascinated, especially by her eyes. The third, a woman, walks away saying, “It’s too scary, I don’t like it.” The first piece of art on my right as I entered the Epic Abstraction exhibition is New York #2 by Hedda Sterne. It’s equally divided between light and dark. Her signature is on the left, in the middle of the vertical plane. My eye is drawn to the dark, the tunnel, the sewer. My mind is working too hard to see and interpret form to allow attention to feeling. Next comes Cy Twombly’s Dutch Interior, which gives me the pleasure and permission of utter foolishness, at scale. “I don’t know what to do.” The artist is present in the action. Time passing. The space covered, not covered, done. Jackson Pollock’s November 28, 1950. Museum clickbait. Overseen. Too confident. Is it his ego I resist? Is it my ego that resists? Moving on. Clyfford Still’s 1950-E. I’m comforted by the burgundy at the bottom. It feels right, balanced, the burgundy, left bottom; blue, right top-ish. Much more black than white, as much grey as black. A comforting painting. The last painting in this first space I entered from the Lilith stair is Conflict (1956-57) by Alfonso Ossorio. My eyes were drawn to this piece when I entered – it’s opposite Sterne’s New York– but I left it until last. It makes me feel alive: the red heart, the three-dimensional explosiveness, with textured paint of varying thickness. The color palate is human – blood, shit, skin, bone. In the middle, more or less, of this first space is Barbara Hepworth’s Single Form (Eikon) (1937-38). I ignored this sculpture the first time I walked through this show, sort of dismissed it. What was that about? It’s too classic, too phallic, too heavy, too large, too squarely confident, too masculine, derivative. The sculpture feels like my past, unlike Lilith and Booker’s Raw Attraction (coming up). But when I force myself to look at it more closely, I’m moved by the wings of the pillar as it expands up a little, by the trickles or ripples down the sides of the square block pedestal, including on the broken corner of the block. Most of the paintings in the Pollock and Rothko rooms slip past me in their familiarity. Kazuo Shiraga’s red and black untitled (1958) is in the Pollock room, right near the entrance to the exhibition from that end. I like it a lot. In the Rothko room, his No. 21 (1949) stands out. It feels uncertain, fading. I expected it to be a significantly early or late painting, but it is dated right in the middle of his painting life. The other piece of art in the Rothko room that stands out to me is Isamu Noguchi’s Kouros, a very large sculpture made of pink Georgian marble. Kouros is a youth, male. This sculpture is not a young man. Or maybe it is. It’s smooth, confident, supple, large, and fragile. The room that really drew my imagination on this visit is the one dominated by Chakaia Booker’s poky, horny, piping, leaking vagina (Raw Attraction) in the corner of the room, flanked on the right by another very large painting (untitled, 1960) by Clyfford Still, this time red is the dominant color, not as comforting as 1950-E (which, by the way, looks ominous from this seat in front of untitled 1960; the black and grey merge from this angle). Still leaves a few light striations, almost drips in the black and in the red. One of these is in the black, right in the center, in the bottom half of the painting. It looks forgotten, a flaw he deliberately forgot. On the left flank of Raw Attraction is Mark Bradford’s Duck Walk (2016). Wow, what a fantastic painting, mixed media. It makes me come alive. The left panel is mostly white with yellow-mustard in the middle, the right panel is black in the middle, yellow swirling out. I see anime faces in the left panel. I like that there is no red in the painting. The color palette is spare. White, black, yellow, and some beige. [Comment added while typing these notes in: His name had sounded familiar, but I only now remembered why. He recently added What Hath God Wrought to the Stuart Collection of remarkable outdoor art at UCSD.] Completing this space are two of my favorite paintings in this show, in large part because they are side by side: Inoue Yūichi’s Kanzan (Cold Mountain, 1966) with stylized renditions of the characters for cold and for mountain and Franz Kline’s Black, White, and Gray, 1959. Almost ending the making of this space is Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 70, 1961. The emotional impact of these artworks in this made space is as much due to the curation, the placement of a work in the space and relative to other pieces, as to each separate artwork itself. And then there is the fabulous, hermetic, almost 21st century video game image – Judit Reigl’s Guano (Menhir), 1959-64, a layered painting: like history, like death, like a reproduction of fallowness – that transitions me into the extraordinary female-human-20th century space dominated by Louise Nevelson’s Mrs. N.’s Palace, 1964-77. -----End of direct notes --- The second trip, of necessity, because of a phone call I was committed to making, ended there. I don’t have notes from the first trip, all I have are memories that are now thoughts in the present. I remember loving the unapologetic size, steadfast standing in place, and geometrical complexity in monochrome grey of Mrs. N.’s Palace, surrounded by sharp-edged images created by men, and also rounded, even sentimental, images created by women. Reds drew me on that first trip as well. I gazed at Alma Thomas’s Red Roses Sonata (1972) and Elizabeth Murray’s Terrifying Terrain (1989-90), and felt the threat and harmony of each. I shied away from, then stared at, Thornton Dial’s Shadows of the Field (2008); now it looks ominously like a faded, tattered flag, millennia before a fossil, though this soft tissue of history and affect is lived in consciousness or disappears. The color palette of Frank Bowling’s Night Journey (1969-70), the yellow falling through the horizontal center, held me, though I found the continents distracting in how they historicized color and shape. Finally, the exhibition ended (or began, if you came in that way) with Yayoi Kusama’s No. B. 62 (1962): mostly evenly red shells or scales, in retrospect a carapace, perhaps the curved surface of that odd creature, a pangolin, laid out in two dimensions. Postscript: I was hesitant to post this piece, even after proofreading it and uploading the photos. This morning, a beautiful, sunny spring day in NYC, I had to make explicit the life and joy I also see in and through the helplessness and moral authority. If you live, you fall in love with life again (thank you, Andrea, for your Facebook cover picture), even if only in small ways, and in that falling in love, you claim life for yourself, and often claim it for others as well. Janie (and Zora Neale Hurston) did that, the Epic Abstraction artists did that. Reading Hurston, and walking through the exhibition, and looking at the sunlight today, I am doing that.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMeenakshi Chakraverti Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed