|

Over the last couple of months, like many people, I have felt pulled and pushed between competing suffering, fear, and, yes, hatred, in, and in relation to, the Palestine-Israel region. I turned for solace to reading and writing. Some of the writers I turned to I’ve known for years. Some I have become aware of in recent weeks. As I’ve read them, I’ve longed for them to hear each other. So I created this conversation of sorts. It’s not really for people who are directly experiencing the suffering of this violent conflict — their pain may be too raw and they are likely consumed with immediate survival and grief — but it’s for the rest of us in the world who are bystanders. Many of us care for both sides. So this conversation of poets and writers is to help us hold, generously, attention to both sides, not condoning cruel actions, but not choosing a side either: not highlighting and mourning the suffering of only one side, nor cheering the combatants of one side or the other. Meenakshi Chakraverti (1)

Note: The quoted poems and writing below are NOT in chronological order. Notes at the end of this imaginary conversation provide dates, sources from which I drew the quotations, and occasionally some additional context. These writers open up possibility. Your reading and reflection will do the same. A conversation among poets and writers Sahir Ludhianvi (Punjabi/Pakistani/Indian) (2): Come let us weave dreams for tomorrow’s sake Else the vicious night of our troubled age Will poison life and heart such that all our lives We’ll be incapable of dreams of love and peace. Toni Morrison (African-American) (3): No more apologies for a bleeding heart when the opposite is no heart at all. Danger of losing our humanity must be met with more humanity. James Baldwin (African-American) (4): Societies never know it, but the war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war, and he does, at his best, what lovers do, which is to reveal the beloved to himself and, with that revelation, to make freedom real. Mahmoud Darwish (Palestinian) through Agha Shahid Ali (Kashmiri) (5): Who am I after the night of the estranged? I wake from my dream, frightened of the obscure daylight on the marble of the house, of the sun’s darkness in the roses, of the water of my fountain; frightened of milk on the lip of the fig, of my language; frightened of wind that—frightened—combs a willow; frightened of the clarity of petrified time, of a present no longer a present; frightened, passing a world that is no longer my world. Irena Klepfisz (American, born in the Warsaw Ghetto) (6): Zi flit she flies vi a foygl like a bird vi a mes like a ghost Zi flit iber di berg over the mountains ibern yam over the sea. Tsurik tsurik back back In der fremd Among strangers iz ir heym is her home. Do Here ot do right here muz zi lebn she must live. Ire zikhroynes her memories will become monuments ire zikhroynes will cast shadows. Amos Oz (Israeli) (7): At first sight this girl seemed to be my age but from the slight curve of her blouse and the unchildlike look of curiosity and also of warning in her eyes as they met mine (for an instant, before my eyes looked away), she must have been two or three years older, perhaps eleven or twelve. Still, I managed to see that her eyebrows were rather thick and joined in the middle, in contrast with the delicacy of her other features. There was a little child at her feet, a curly-haired boy of about three who may have been her brother; he was kneeling on the ground and was absorbed in picking up fallen leaves and arranging them in a circle. Boldly and all in one breath I offered the girl a quarter of my entire vocabulary of foreign words, perhaps less like a lion confronting other lions and more like the parrots in the room upstairs. Unconsciously I even bowed a little bow, eager to make contact and thus to dispel any prejudices and to advance the reconciliation between our peoples: “Sabah al-heir, Miss. Ana ismi Amos. Wa-inti, ya bint? Votre nom s’il vous plaît, Mademoiselle? Please your name kindly?” She eyed me without smiling. Her joined eyebrows gave her a severe look beyond her years. She nodded a few times, as though making a decision, agreeing with herself, ending the deliberation, and confirming the findings. Her navy blue dress came down below her knees, but in the gap between the dress and her socks with the butterfly buckles I caught sight of the skin of her calves, brown and smooth, feminine, already grown up; my face reddened, and my eyes fled again, to her little brother, who looked back at me quietly, unsuspectingly, but also unsmilingly. Suddenly he looked very much like her with his dark, calm face. Everything I had heard from my parents, from neighbors, from Uncle Joseph, from my teachers, from my uncles and aunts, and from rumors came back to me at that moment. Everything they said over glasses of tea in our backyard on Saturdays and on summer evenings about mounting tensions between Arab and Jew, distrust and hostility, the rotten fruit of British intrigues and the incitement of Muslim fanatics who painted us in a frightening light to inflame the Arabs to hate us. Our task, Mr. Rosendorff once said, was to dispel suspicions and to explain to them that we were in fact a positive and even kindly people. In brief, it was a sense of mission that gave me the courage to address this strange girl and start a conversation with her: I meant to explain to her in a few convincing words how pure our intentions were, how abhorrent was the plot to stir up conflict between our two peoples, and how good it would be for the Arab public — in the form of this graceful-lipped girl — to spend a little time in the company of the polite, pleasant Hebrew people, in the person of me, the articulate envoy aged eight and a half. Almost. But I had not thought out in advance what I would do after I had used up most of my supply of foreign words in my opening sentence. How could I enlighten this oblivious girl and get her to understand once and for all the rightness of the Jewish return to Zion? By charades? By dance gestures? And how could I get her to recognize our right to the Land without using words? How, without any words, could I translate for her Tchernikhowsky’s “O, my land, my homeland”? Or Jabotinsky’s “There Arabs, Nazarenes and we / shall drink our fill in happy manner, / when both the banks of Jordan’s stream / are purged by our unsullied banner?” In a word, I was like that fool who had learned how to advance the king’s pawn two squares, and did so without any hesitation, but after that had no idea at all about the game of chess, not even the names of the pieces, or how they moved, or where, or why. Lost. But the girl answered me, and actually in Hebrew, without looking at me, her hands resting open on the bench on either side of her dress, her eyes fixed on her brother, who was laying a little stone in the center of each leaf in his circle. “My name is Aisha. That little one is my brother. Awwad.” She also said: “You’re the son of the guests from the post office?” And so I explained to her that I was definitely not the son of the guests from the post office, but of their friends. And that my father was a rather important scholar, an ustaz, and that my father’s uncle was an even more important scholar, who was even world famous, and that it was her honored father, Mr. Silwani, who had personally suggested that I should come out in the garden and talk to the children of the house. Aisha corrected me and said that Ustaz Najib was not her father but her mother’s uncle: she and her family did not live here in Sheikh Jarrah but in Talbieh, and she herself had been going to lessons from a piano teacher in Rehavia for the past three years, and she had learned a little Hebrew from the teacher and the other pupils. It was a beautiful language, Hebrew, and Rehavia was a beautiful area. Well kept. Quiet. Talbieh was well kept and quiet, too, I hastened to reply, repaying one compliment with another. Would she be willing for us to talk a little? Aren’t we talking already? (A little smile flickered for an instant around her lips. She straightened the hem of her dress with both her hands, and crossed and uncrossed and recrossed her legs. And for an instant her knees appeared, the knees of a grown-up woman already, then her dress straightened again. She looked slightly to my left now, where the garden wall peered at us among the trees.) I therefore adopted a representative position, and expressed the view that there was enough room in this country for both peoples, if only they had the sense to live together in peace and mutual respect. Somehow, out of embarrassment or arrogance, I was talking to her not in my own Hebrew but in that of Father and his visitors: formal, polished. Like a donkey dressed up in a ballgown and high-heeled shoes: convinced for some reason that this was the only proper way to speak to Arabs and girls. (I had hardly even had an occasion to talk to a girl or an Arab, but I imagined that in both cases a special delicacy was required: you had to talk on tiptoe, as it were.) It transpired that her knowledge of Hebrew was not extensive or perhaps her views were not the same as mine. Instead of responding to my challenge, she chose to sidestep it: her elder brother, she told me, was in London, studying to be a “solicitor and a barrister.” Puffed up with representativity, I asked her what she was thinking of studying when she was older. She looked straight into my eyes, and at that moment, instead of blushing, I turned pale. Instantly I averted my eyes, and looked down at her serious little brother Awwad, who had already laid out four precise circles of leaves at the foot of the mulberry tree. How about you? Well. you see, I said, still standing, facing her, rubbing my clammy palms against the sides of my shorts, well, you see, it’s like this — You’ll be a lawyer too. From the way you speak. What makes you think that exactly? Instead of replying, she said: I’m going to write a book. You? What kind of book will you write? Poetry. Poetry? In French and English. You write poetry? She also wrote poetry in Arabic, but she never showed it to anyone. Hebrew was a beautiful language, too. Had anyone written any poetry in Hebrew? Shocked by her question, swollen with indignation and a sense of mission, I began there and then to give her an impassioned recital of snatches of poetry. Tchernikhowsky. Levin Kipnes. Rahel. Vladimir Jabotinsky. And one poem of my own. Whatever came to mind. Furiously, describing circles in the air with my hands, raising my voice, with feeling and gestures and facial expressions and occasionally even closing my eyes. Even her little brother Awwad raised his curly head and fixed me with brown, innocent lamblike eyes, full of curiosity and slight apprehension, and suddenly he recited in clear Hebrew: Jest a minute! Rest a minute! Aisha, meanwhile, said nothing. Suddenly she asked me if I could climb trees. Mahmoud Darwish (Palestinian) (8): My sky is ashen. Scratch my back. And undo slowly, you stranger, my braids. And tell me what’s on your mind. Tell me what crossed Youssef’s mind. Tell me some simple talk … the talk a woman always desires to be told. I don’t want the phrase complete. Gesture is enough to scatter me in the rise of butterflies between springheads and the sun. Tell me I am necessary for you like sleep, and not like nature filling up with water around you and me. And spread over me an endless blue wing … Naomi Shihab Nye (Palestinian American) (9): The man with laughing eyes stopped smiling to say, “Until you speak Arabic, you will not understand pain.” Something to do with the back of the head, an Arab carries sorrow in the back of the head that only language cracks, the thrum of stones weeping, grating hinge on an old metal gate. “Once you know,” he whispered, “you can enter the room whenever you need to. Music you heard from a distance, the slapped drum of a stranger’s wedding, wells up inside your skin, inside rain, a thousand pulsing tongues. You are changed.” Outside, the snow had finally stopped. In a land where snow rarely falls, we had felt our days grow white and still. I thought pain had no tongue. Or every tongue at once, supreme translator, sieve. I admit my shame. To live on the brink of Arabic, tugging its rich threads without understanding how to weave the rug … I have no gift. The sound, but not the sense. Hayyim Nahman Bialik (born in the Russian Empire, Jewish) (10): …Get up and walk through the city of the massacre, And with your hand touch and lock your eyes On the cooled brain and clots of blood Dried on tree trunks, rocks, and fences; it is they. Go to the ruins, to the gaping breaches, To walls and hearths, shattered as though by thunder: Concealing the blackness of a naked brick, A crowbar has embedded itself deeply, like a crushing crowbar, And those holes are like black wounds, For which there is no healing or doctor. Take a step, and your footstep will sink: you have placed your foot in fluff, Into fragments of utensils, into rags, into shreds of books: Bit by bit they were amassed through arduous labor—and in a flash, Everything is destroyed… And you will come out into the road-- Acacias are blooming and pouring their aroma, And their blooms are like fluff, and they smell as though of blood. And their sweet fumes will enter your breast, as though deliberately, Beckoning you to springtime, and to life, and to health; And the dear little sun warms and, teasing your grief, Splinters of broken glass burn with a diamond fire-- God sent everything at once, everyone feasted together: The sun, and the spring, and the red massacre! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hayim_Nahman_Bialik David Grossman (Israeli) (11): See Under: Love is a novel about a story that was lost, torn to shreds. There are several such lost stories in the book, which have to be told again and again because that is the only way to assemble the traces of identity and fuse the fragments of a crumbled world. Many characters in the book are looking for a story they have lost, usually a childhood tale, and they need it very badly so that they can retell it, as adults, and be reborn through it. It is not innocence that drives their desire to tell children’s stories, for they have virtually no innocence left. Rather, this is their way to preserve their humanity, and perhaps a modicum of nobility — to believe in the possibility of childhood in this world, and to hold it up against the sheer cynicism. To tell the whole story again through the eyes of a child. Hiba Abu Nada (Palestinian) (12): I shelter you and the children who are sleeping as chicks in the lap of their nest they don’t walk in their dreams because death towards the house walks …. I shelter you from wound and woe, and with seven verses I shield the taste of orange from phosphorus, the color of clouds from smoke. https://lithub.com/a-palestinian-meditation-in-a-time-of-annihilation/ Ben Ehrenreich (American)/Asmaa al-Ghoul (Palestinian) (13): When Hamas breached the walls surrounding Gaza on October 7, al-Ghoul said, “I was happy.” Not because Israeli civilians had been killed—that news, which filled her with sadness, shame, and fear, had not yet reached her—but because, she said, “we thought this will move something,” that finally, something might shift and the slow, steady strangulation under which Gaza had lived since 2007 might be broken. “We didn’t know the rest of the story,” she said. In those early hours, before word got out about the killings in the kibbutzim and the Israeli towns outside the Strip and at the music festival, this is what people were celebrating. We thought the targets were military, al-Ghoul said, and for a moment she allowed herself some giddy hope that some real victory might come of it, that Israel could be forced to end its siege so “we can come and go like normal people,” free to drive across their own country. “This is what I miss,” she said, “I miss the good air, just to visit, to have a home.” She couldn’t finish the thought. Sobs overwhelmed her. Her voice crumbled into a moan. She waved her hand at the images flashing across the television screen, more bodies covered in gray dust. “Look what happened,” she said, “they destroyed it. They destroyed Gaza.” The first neighborhood to be razed, she said, was al-Rimal, in Gaza City. Her family had lived there in a rented house for most of the last 19 years. “It was one of the most beautiful places in Gaza.” She brought up a photo on her phone, a vast, nonsensical geometry of twisted concrete and buildings collapsed in on themselves. It was captioned in French: “Ma maison était ici,” My house was here. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/death-in-the-air?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Lit%20Hub%20Daily:%20November%209%2C%202023&utm_term=lithub_master_list Lily Galili (Israeli) (14): Some years ago, I worked on a series of articles on mixed cities in Israel where Jews and Arabs live together (Akko, Ramla, Lod, Yaffo etc). All throughout this ordeal I felt accompanied by two ghosts: one of my mother, a holocaust survivor dead by then, the other of an old Palestinian refugee. Both stared at me with anticipation; both whispered in my ear: “this land is my land.” I’ve known, by then, I cannot fully satisfy both. I can only recognize the drama and the tragedy of one of them, and try to minimize the damage and the pain of the other. I chose my mother, over and over again…. My intricate relationship with Zionism started on the wrong foot. As a child growing up in communist Poland, I was madly in love with then long dead Stalin. When my mother announced we were leaving for Palestine (that’s how she referred to Israel), I was less than ecstatic…. And then I fell in love again. This time with this crazy, pained and pain-inflicting country. Decades of participation in anti-war and pro-peace demonstrations, learning to live with the unfulfilled promise of a safe-haven certainly caused some erosion, but never destroyed my self-definition as a Zionist. Just the opposite, it made me an all-Zionist girl. I’m the liberal “peacenik” at rallies, but also the settler from an illegal outpost. One day I might feel closest to an Israeli Arab and on another day, I might identify with an American Jew. Ultimately, my Zionism is about shouldering collective burden. I feel responsible for everything that goes wrong in Israel and I rejoice in the little that goes right. I am the All-Zionist girl. I know it sounds terribly self serving. It’s not. If anything, it’s selfish. I know, from experience, I could never live again in a place where I am a minority. I’d rather struggle with the often non-democratic nature of Israel , the lack of social justice, the cruelty of occupation, the constant sense of guilt, and do (almost) the best I can to change it. From here, from within. Yet my Zionism stops at the Green Line. https://www.thedailybeast.com/all-zionist-girl Fady Joudah (Palestinian American) (15): As I witness my collective Palestinian death unfold live on digital media and non-American TV, as I have become “a river of bodies into one,” a conduit for common decency, condolences, solidarity that affirms and elevates me, a survivor who has his dead, a survivor with a familiar name, relatable sound, relevant corpus, a vessel for the outpouring of empathy whose primary mode offers me the visibility that can’t be uncoupled from market forces—and it is true that my books, along with those of several Palestinian writers, have been selling well since, in my case, I have announced my dead to America, at least until the mainstream media became uninterested in parading my grief, since my grief did not come without troublesome talk about equal humanity, a political condition for freedom, an unthinkable condition for the US and Israel vis-a-vis Palestinians, a condition whose absence is necessary for the continued destruction of Palestinian life. … But I have a more daring question. The Israeli people at large, the Jewish communities outside Israel that identify strongly or faintly, defensively or hawkishly with Israel, the mainstream Western world, and all expressions of Zionism, what do they want from Palestinians? In the best-case scenario, I do not think they really know. I am terrified to think that this relentless progression of dispossession and carnage against the Palestinians has reached irreversible, irrational levels. In my dark hours, which increase by the year, I wonder if Israel is unable to examine or defuse its impulse to test the limits of genocide against the Palestinians—because it has not been able to process the genocide that the Nazis committed against the Jewish people. A genocide that was made possible by centuries of European antisemitism, pogroms, silence, and looking away. https://lithub.com/a-palestinian-meditation-in-a-time-of-annihilation/ David Grossman (Israeli) (16): But the cracks in the sense of security are deeper and more fundamental : in recent years, the years of the second intifada, Israelis have been living in a world in which people are, quite literally, being ripped apart. Entire families are killed in the blink of an eye, human limbs are severed in cafes, shopping malls, and buses. These are the materials of Israeli reality and the nightmares of every Israeli, and the two are inseparably mingled. Much of daily life in Israel now occurs in the pre-cultural, primitive, animalistic regions of terror. Fierce violence is employed against the Israelis, and they respond with equal ruthlessness against the Palestinians. To be an Israeli today means to live with the perception that we have lost our path and that we are living in a dismantled state, in every sense — the dismantling to the private, human body, whose fragility is exposed over and over again, and the dismantling of the public general body. Deep fault lines have emerged in recent years in the various branches of government, in the authority of the law and of the courts, in the credibility of the army and the police, and in the trust that the public affords its leaders and its faith in their integrity. Ben Ehrenreich (American)/Asmaa al-Ghoul (Palestinian) (17): Death on television isn’t death. It’s an image, a recyclable flash of pixelated light accompanied by commentary, chatter, noise, the obscenity of cliché. It can be bent into some semblance of meaning, inserted into one or another political narrative. But when you’re there, al-Ghoul said, what stands out is the silence. “It’s very quiet.” Bodies that minutes earlier were warm and alive are cold and still. And then there’s the smell, which no screen can convey. “I smell the death in the air even though I am not there,” al-Ghoul said. “When I go out, when I walk, there’s death in my eyes. I cannot live like before. My eyes are full of death.” David Grossman (Israeli) (18): I feel the heavy price that I and the people around me pay for this prolonged state of war. Part of this price is a shrinking of our soul’s surface area — those parts of us that touch the violent, menacing world outside — and a diminished ability and willingness to empathize at all with other people in pain. We also pay the price by suspending our moral judgement, and we give up on understanding what we ourselves think. Given a situation so frightening, so deceptive, and so complicated — both morally and practically — we feel it may be better not to think or know. Better to hand over the job of thinking and doing and setting moral standards to those who are surely “in the know.” Fady Joudah (Palestinian American) and Mahmoud Darwish (Palestinian) (19): Around 1988, during the first Intifada, Darwish was a member of the executive council in the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). Along with Edward Said, he was assigned the task of drafting a new charter toward peace. It was a prickly and odd time for Darwish, “for what is a poet doing there, there in the executive council?” he asked himself. In an essay titled “Before Writing My Resignation,” Darwish became uncomfortably aware how “the creative Palestinian is prohibited from the luxury of vacated and dedicated time for the sake of creativity, because this is bound to a direct cessation from patriotic activity. Yet prisoners grow flowers in their prison yards. And in front of the zinc huts mothers plant basil and mint. The creative person must create his flexible margin between the patriotic, the political, the daily, the cultural, and the literary. But what am I to do? What does a poet do in the executive council? Will I be able to write a book of love when color falls on the ground in autumn?” David Grossman (Israeli) (20): In this reality, we authors and poets write. In Israel and in Palestine, in Chechnya and in Sudan, in New York and in the Congo. There are times in my workday, after a few hours of writing, when I look up and think: Now, at this very moment, sits another author, whom I do not know, in Damascus or Tehran, in Kigali or Dublin, who, like me, is engaged in the strange, baseless, wonderful work of creation, within a reality that contains so much violence and alienation, indifference and diminishment. I have a distant ally who does not know me, and together we are weaving this shapeless web, which nonetheless has immense power, the power to change a world and create a world, the power to give words to the mute and to bring about tikkun — “repair” — in the deepest, kabbalistic sense of the word. … It is hard to talk about yourself. I will only say what I can say at this time, from where I stand now. I write. The consciousness of the disaster that befell me upon the death of my son Uri in the Second Labanon War now permeates every minute of my life. The power of memory is indeed great and heavy, and at times has a paralyzing effect. Nevertheless, the act of writing creates for me a “space” of sorts, an emotional expanse that I have never known before, where death is more than the absolute, unambiguous opposite of life. … I write, and the world does not close in on me. It does not grow smaller. It moves in the direction of what is open, future, possible. … I write. And all at once I am no longer doomed to face this absolute, false, suffocating dichotomy — this inhuman choice between “victim” and “aggressor,” without any third, more human option. When I write, I can be a whole person, with natural passages between my various parts, and with some parts that feel close to the suffering and the just assertions of my enemies without giving up my identity at all. Fady Joudah (Palestinian American) (21): [Mahmoud Darwish’s] The Stranger’s Bed is a journey of, and through voice. There is a delicate speech that gives birth to itself here. There is an “I” that overflows from the “you,” and a duality that merges beyond the narrow constructs of language. There is dialogue between masculine and feminine, prose and poetry, self and its others. Not enough can be said about the metaphysics of identity in this book of love. An appeal to healing begins the collection: “We came / with the wind to Babylon / and we march to Babylon,” “Am I another you / and you another I?” “Then let’s be kind.” The subtle dialogue between tone and cadence in poems such as “Low Sky” and “We Walk on the Bridge” ushers the tender musical exchange throughout the book, where even the mythic can be treated with “one cup of hot chamomile / and two aspirins.” And the sonnets — a stranger’s template for another vernacular — develop the spine that gives the book its sway as man and woman, poetry and prose, commune with each other. Duality (or the annihilation of it) becomes “the necessary clarity of our mutual puzzle.” In many respects The Stranger’s Bed is a conversation that, once begun, compels the reader through to its last utterance, uninterrupted, where the Familiar and the Stranger become “two in one.” David Grossman (Israeli) (22): Who will we be when we rise from the ashes and re-enter our lives? When we viscerally feel the pain of author Haim Gouri’s words, written during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, “How numerous are those no longer with us.” Who will we be and what kind of human beings will we be after seeing what we’ve seen? Where will we start after the destruction and loss of so many things we believed in and trusted? … Are we capable of shaking off the well-worn formulas and understanding that what has occurred here is too immense and too terrible to be viewed through stale paradigms? Even Israel’s conduct and its crimes in the occupied territories for 56 years cannot justify or soften what has been laid bare: the depth of hatred towards Israel, the painful understanding that we Israelis will always have to live here in heightened alertness and constant preparedness for war. In an unceasing effort to be both Athens and Sparta at once. And a fundamental doubt that we might ever be able to lead a normal, free life, unfettered by threats and anxieties. A stable, secure life. A life that is home. https://www.jta.org/2023/10/20/ideas/israeli-novelist-david-grossman-who-will-we-be-when-we-rise-from-the-ashes Mahmoud Darwish (Palestinian) (23): We store our sorrows in our jars, lest the soldiers see them and celebrate the siege … We store them for other seasons, for a memory, for something that might surprise us on the road. But when life becomes normal we’ll grieve like others over personal matters that bigger headlines had kept hidden, when we didn’t notice the hemorrhage of small wounds in us. Tomorrow when the place heals we’ll feel its side effects Naomi Shihab Nye (Palestinian American) (24): Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside, you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing. You must wake up with sorrow. You must speak to it till your voice catches the thread of all sorrows and you see the size of the cloth. Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore, only kindness that ties your shoes and sends you out into the day to gaze at bread, only kindness that raises its head from the crowd of the world to say It is I you have been looking for, and then goes with you everywhere like a shadow or a friend. David Grossman (Israeli) (25): I conclude with one more wish, which I once expressed in my novel See Under: Love. This wish is uttered at the very end of the book, when a group of persecuted Jews in the Warsaw ghetto finds an abandoned baby boy and decides to raise him. These elderly Jews, broken and tortured, stand around the child and dream about what they would like his life to be, and into what sort of a world they would like him to grow up. Behind them, the real world is going up in smoke, with blood and fire everywhere, and they say a prayer together. This is their prayer: “All of us prayed for one thing: that he might end his life knowing nothing of war … We asked so little: for a man to live in this world from birth to death and know nothing of war.” Nikola Madzirov (Macedonian) (26): I saw dreams that no one remembers and people wailing at the wrong graves. I saw embraces in a falling airplane and streets with open arteries. I saw volcanos sleep longer than the roots of the family tree and a child who’s not afraid of the rain. Only it was me no one saw only it was me no one saw. Agha Shahid Ali (Kashmiri) (27): Your history gets in the way of my memory. I am everything you lost. You can't forgive me. I am everything you lost. Your perfect enemy. Your memory gets in the way of my memory: … I'm everything you lost. You won't forgive me. My memory keeps getting in the way of your history. There is nothing to forgive. You won't forgive me. I hid my pain even from myself; I revealed my pain only to myself. There is everything to forgive. You can't forgive me. If only somehow you could have been mine, what would not have been possible in the world? Joy Harjo (Mvskoke) (28): To pray you open your whole self To sky, to earth, to sun, to moon To one whole voice that is you. And know there is more That you can’t see, can’t hear; Can’t know except in moments Steadily growing, and in languages That aren’t always sound but other Circles of motion. Like eagle that Sunday morning Over Salt River. Circled in blue sky In wind, swept our hearts clean With sacred wings. We see you, see ourselves and know That we must take the utmost care And kindness in all things. Breathe in, knowing we are made of All this, and breathe, knowing We are truly blessed because we Were born, and die soon within a True circle of motion, Like eagle rounding out the morning Inside us. We pray that it will be done In beauty. In beauty. Audre Lorde (African-American) (29): Hatred is the fury of those who do not share our goals and its object is death and destruction. Anger is a grief of distortions between peers, and its object is change. … The angers between [peers] will not kill us if we can articulate them with precision, if we listen to the content of what is said with at least as much intensity as we defend ourselves against the manner of saying. When we turn from anger we turn from insight, saying we will accept only the designs already known, deadly and safely familiar. I have tried to learn my anger’s usefulness to me, as well as its limitations. … The angers of [peers] can transform difference through insight into power. For anger between peers births change, not destruction, and the discomfort and sense of loss it often causes is not fatal but a sign of growth. *** Meenakshi: These poets and writers open up possibility. But you — people of strategy and action — need to build the structures and make possibility into reality. Do it. NOTES: (1) Who am I? Why do I care? Why these writers? FWIW, what do I think? I am Meenakshi Chakraverti, an US American of Indian-Bengali origin. I am a writer, living in NYC. I live on land that was inhabited by the peoples of Lenapehoking. Descendants of the Lenape and other indigenous communities continue to live on this land that has been settled, often with violence and theft, by waves of settlers, including me, from other parts of the world. I honor them and I own that history. I chose to become an American citizen and over the last two decades have been learning to live with American history as my history. Having grown up as a member of an upper-caste Hindu family, I am also learning to be more conscious of, and own, my caste history. I am aware that this war in Palestine-Israel is just one of many wars, and many other wars cause grievous harm without me feeling so stirred. So why this war, this region? In my case, two things: (1) Early in my life I grew up with the grief of the Holocaust (a horror and a grief for ALL people; we are all accountable), and then I became increasingly aware of the losses and plight of Palestinians. I know Israelis personally and have good Jewish friends who have family in Israel. And I’ve worked with Israelis and Palestinians in Second Track dialogue work and grew to have a personal fondness for all of them. So there is a real personal connection with that region. (2) I am a US citizen. The US continues to be inordinately powerful and influential in that region, as much or more than it is any other region. As a US citizen, I am accountable for the policies of the US. Most of the quoted writers are people whose writing I know and admire. A few are new to me but their writing has made me think and feel in ways that open up understanding and possibility. They all have written things that “the other side” might “disagree” with, and they all have written things that show they see something and feel something of what “the other side” sees and feels. A long time ago, after the Oslo Accords collapsed and the Second Intifada had started I did some work with a group of Palestinians and Israelis. Most of them were writers; all of them worked with words. In one of the breaks between their facilitated conversations, they sat together. They took a long break. At the end, they turned to us, and said: “if it were up to us, we’ve resolved the conflict.” I do believe that if the writers I’ve quoted here were to meet — for all the pain and anger that those still alive feel right now — they would have a different conversation from the engagements between the Israeli leadership, especially Netanyahu and his government, and the Palestinian leadership, especially Hamas. I believe they might well find a way to resolution and the rest of us in the world would rejoice. But many of the writers quoted here aren’t still alive, and those who are, don’t get to meet and certainly don’t get to decide the way forward. However, perhaps, we, who read them, can push our leaders to hear and amplify their voices. What happens next? I have no solutions, but I see the possibility of peace (yes, really, even today!) and I have no choice but to hope. I have no standing from which to propose or build solutions but I do think that I and others like me —bystanders who care — can create space for people who are more immediately affected to breathe, feel, and think with less rather than more fear and thus to be more active supporters and participants in a real peace process. Perhaps a peace process could start with recognizing the state of Palestine with 1967 borders. Let’s seek and support people brave enough to make this a peaceful and prosperous region for all. (2) This excerpt is from a poem by Sahir Ludhianvi, the pen name of Abdul Hayee, a poet and writer born in 1921 in Ludhiana, Punjab. I was introduced to this poem by Punjabi (both Pakistani and Indian) partners in Sahar, a Boston area-based dialogue effort in the early 2000s. This translation is based on the translation I was given, perhaps slightly modified by me. I have not found any source with this exact translation. Here is a transliteration of the original Urdu. The link also leads to a video of the poem being read. aao ki koī ḳhvāb buneñ kal ke vāste varna ye raat aaj ke sañgīn daur kī Das legī jaan o dil ko kuchh aaise ki jaan o dil tā-umr phir na koī hasīñ ḳhvāb bun sakeñ https://www.rekhta.org/nazms/aao-ki-koii-khvaab-bunen-aao-ki-koii-khvaab-bunen-kal-ke-vaaste-sahir-ludhianvi-nazms (3) “The War on Error” (in the section titled The Foreigner’s Home) in The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations by Toni Morrison. (4) “The Creative Process” by James Baldwin. (5) From “Eleven Stars Over Andalusia” by Mahmoud Darwish, the English version by Agha Shahid Ali, with Ahmad Dallal. Agha Shahid Ali was a Kashmiri poet writing in English. The original poem was written in Arabic. (6) From “Di rayze aheym/The Journey Home” by Irena Klepfisz, in Her Birth and Later Years: New and Collected Poems, 1971-2021. Klepfisz’s mother was a Holocaust survivor and her father was killed in the Warsaw Ghetto. (7) From A Tale of Love and Darkness by Amos Oz (translated from the Hebrew by Nicholas de Lange). This excerpt is situated in the summer of 1947 in British-ruled Palestine. (8) From “Two Stranger Birds in Our Feathers” by Mahmoud Darwish (from the collection The Stranger’s Bed, translated from the Arabic by Fady Joudah). (9) From “Arabic” by Naomi Shihab Nye (from her collection Red Suitcase). (10) From “In the City of Slaughter” by Hayim Nahman Bialik, written in 1904 about the 1903 Kishinev pogrom in Moldova which was part of the Russian Empire (translated from the Hebrew by Vladimir Jabotinsky). I found this version on Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hayim_Nahman_Bialik. (11) From “Books That Have Read Me,” an essay by David Grossman, published in the English collection titled Writing in the Dark (translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen). (12) This poem by Hiba Abu Nada is quoted by Fady Joudah, in his essay titled “A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation,” published on November 1, 2023 by Literary Hub. Hiba Abu Nada died in the bombing of Gaza on Oct 20, 2023. (https://lithub.com/a-palestinian-meditation-in-a-time-of-annihilation/) (13) From “Death in the Air” by American writer Ben Ehrenreich, in which he interviews Gazan writer Asmaa al-Ghoul (blog post 8 November 2023). https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/death-in-the-air?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Lit%20Hub%20Daily:%20November%209%2C%202023&utm_term=lithub_master_list (14) From “All-Zionist Girl” by Lily Galili, in The Daily Beast, April 27, 2012. Lily Galili is a major Israeli journalist. https://www.thedailybeast.com/all-zionist-girl (15) From “A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation,” by Fady Joudah. See (12). (16) From “Contemplations on Peace,” by David Grossman, in the collection Writing in the Dark. See (11). (17) Same as (13). (18) From “Writing in the Dark,” by David Grossman, in the collection Writing in the Dark. (19) From the Translator’s Preface, by Fady Joudah, to the collection of poems of different periods, The Butterfly’s Burden, by Mahmoud Darwish. (20) Same as (18). (21) Same as (19). (22) From “Who will we be when we rise from the ashes,” by David Grossman, published by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on October 20, 2023. https://www.jta.org/2023/10/20/ideas/israeli-novelist-david-grossman-who-will-we-be-when-we-rise-from-the-ashes. (23) From “ A State of Siege,” by Mahmoud Darwish, translated by Fady Joudah in The Butterfly’s Burden. See (19). (24) From “Kindness” by Naomi Shihab Nye, from her selected poems in Words Under the Words. (25) From “Contemplations on Peace,” by David Grossman, in the collection Writing in the Dark. (26) From “I saw Dreams” by Nikola Madzirov, published in How Does the World Breathe Now? Film as Witness, Archive, and Political Tool, by Savvy Contemporary, Berlin. Translated from the Macedonian by Peggy and Graham Reid. (27) From “Farewell,” by Agha Shahid Ali, in his collection of poems, The Country Without a Post Office. (28) From “Eagle Poem, by Joy Harjo, from her collection In Mad Love and War. (29) From “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism,” by Audre Lorde, keynote presentation at the National Women’s Studies Association Conference, June 1981, and in the collection Sister Outsider.

0 Comments

The children of today become the grown-ups of tomorrow. The grown-ups of today are the children of yesterday.

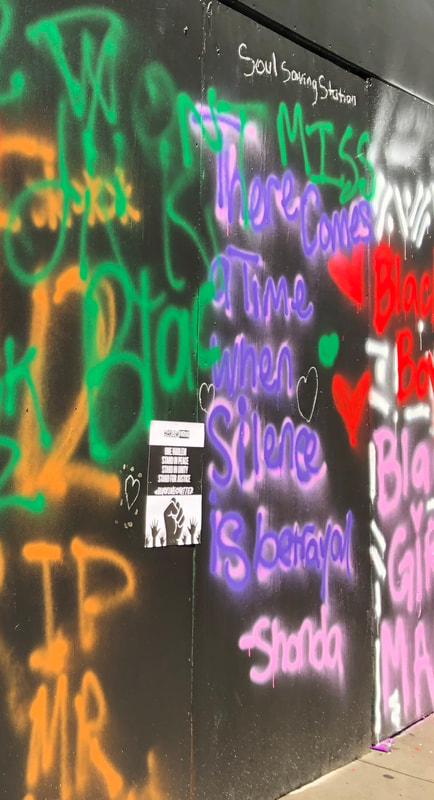

Many years ago I was invited to a fundraiser for a program called Hands of Peace which created space for Palestinian/Arab and Israeli/Jewish teenagers to live together for a few weeks and engage in full and honest encounters. The children spoke at the fundraiser and from what I could tell they had many very important and very challenging conversations. How challenging? Think how challenging it is today to talk to someone who thinks even a little differently from you on the topic of Palestine and Israel, leave alone people who think “Israelis” are the bad guys (as if all Israelis are the same) or “Palestinians” are the bad guys (as if all Palestinians are the same), leave alone people who because of deep relational or cultural or historical connections to Palestine or Israel, and to the suffering woven into each of those histories, feel that each word — just listening to it — has the potential to destroy or at least draw blood. These children did it. Held by Hands of Peace, they had these conversations. They didn’t, indeed couldn’t, solve the conflict, but they created a tender foundation of relationships that the grown-ups they would become, perhaps, could draw on to build peace in their region. As I write this, I am sad and somewhat fearful thinking of those children, now in their late twenties. Who are they now? How are they? What’s left of the tender foundation of relationships? A silent auction was one of the mechanisms of the fundraiser. A box with an embroidered cover was contributed by a young Palestinian, a girl if I remember correctly. A large metal hamsa hand was brought by a young Israeli, a boy, as I remember. They looked like elements of home, they looked like they belonged in a home, and I could afford them, so I bid for them and now they are side by side in my living room, in a central place. I brought these objects to my home many years after some work I’d done with Palestinians and Israelis, whom I’d grown to like and respect, all of them. That work happened at a time when I still hoped for change. Then, as one barrier to peace after another was layered and stacked, often with the blood and tears of someone, or someone else, and sometimes with the bland words of political and bureaucratic “strategies,” I looked away. The box and the hand stayed in my living room in a central place, perhaps silently holding hope. Perhaps those children will…? And, now, I have been shocked out of my looking away, though I’m tempted to look away again. I could look away, utter some platitudes, and look away once more, but I will not. This time I will not look away and I’m writing this to ask you not to as well. This is not simply about safety, land and dignity, ceasefire, or justice, though all of those things are important for Israelis as well as Palestinians. It’s about the children. It’s about the grown-ups we want tomorrow. While the violence and kidnappings committed on October 7, 2023 by Hamas militants were unambiguously cruel and wrong, I knew they would be followed by “lawn-mowing.” As I struggled with external and internal responses to the Hamas violence and Israel’s relentless bombing of Gaza, killing and maiming tens of thousands, destroying homes and hospitals, along with a sideshow of beatings and vandalism in the West Bank, I went back to writers I’ve admired: Mahmoud Darwish, Amos Oz, David Grossman, Naomi Shihab Nye. I read news commentaries carefully, looking for more than escalating fear and hatred; looking rather for kindness and empathy that goes both ways even if not quite symmetrically, for glimpses of generosity in the midst of anger and pain. I created a conversation of sorts among poets and writers, using quoted excerpts of their work. As I read the conversation I’d composed, I wondered why everyone doesn’t see: there’s beauty here (I look one way) and there’s beauty there (I look the other way); there’s pain here, there’s pain there; there’s anger here, there’s anger there; there’s kindness here, there’s kindness there; there’s love here, there’s love there; there’s fear here, there’s fear there. I want to write — it fits the cadence of the words and the sentiment cloud I am conjuring up — there’s hope here, there’s hope there, but I can’t. There isn’t much hope, here or there. If we care about that region, it’s up to us to create space for hope for all the peoples of Palestine and Israel. And I believe that the content and direction of the hope can only be a fair, robust, and viable peace process. It can be slow, it can even be angry, so long as anger is seen, as I learned from Audre Lorde, as a “distortion of griefs among peers.” Indeed anger in this context is a distortion of griefs, but can Israelis and Palestinians see each other as peers? Do we in the rest of the world hold them as peers, hold space for them as peers? If anger is not expressed and understood and explored as a distortion of griefs among peers, it drops into hatred, and “the object of hatred,” as Lorde puts it, “is death and destruction.” Peace does not mean stepping away from anger, “for anger between peers births change, not destruction, and the discomfort and sense of loss it often causes is not fatal, but a sign of growth.” (from “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism” in Sister Outsider) Scouring the news for reasons to hope I watched a brief video on The Washington Post website that shows displaced Palestinian teenaged boys doing parkour, watched by delighted little children. A teenager who is interviewed explains that it’s an outlet from the stresses of the war and the delight of the little children makes him happy. I watched it thinking of David Grossman’s wish. In his essay, “Contemplations on Peace,” he writes: “I conclude with one more wish, which I once expressed in my novel See Under: Love. This wish is uttered at the very end of the book, when a group of persecuted Jews in the Warsaw ghetto finds an abandoned baby boy and decides to raise him. These elderly Jews, broken and tortured, stand around the child and dream about what they would like his life to be, and into what sort of a world they would like him to grow up. Behind them, the real world is going up in smoke, with blood and fire everywhere, and they say a prayer together. This is their prayer: “All of us prayed for one thing: that he might end his life knowing nothing of war … We asked so little: for a man to live in this world from birth to death and know nothing of war.” (in Writing in the Dark) This wish — my wish, your wish I hope — is not just for happy children, it’s for the grown-ups — whether Israeli or Palestinian— who can be so much more if they are not consumed by fear of destruction and destructive themselves. Little children are sweet and innocent and, of course, we don’t want them to be harmed. But, as importantly, these children grow up to be the grown-ups who govern our world and the world of new generations of sweet and innocent children. Wouldn’t you want grown-ups who know and can give generosity and joy, because they have received it, rather than grown-ups who live with grieving and fearful barriers, hardened by and into hatred, barriers which open more easily to violence than to generosity? Composition: the artist as impostor

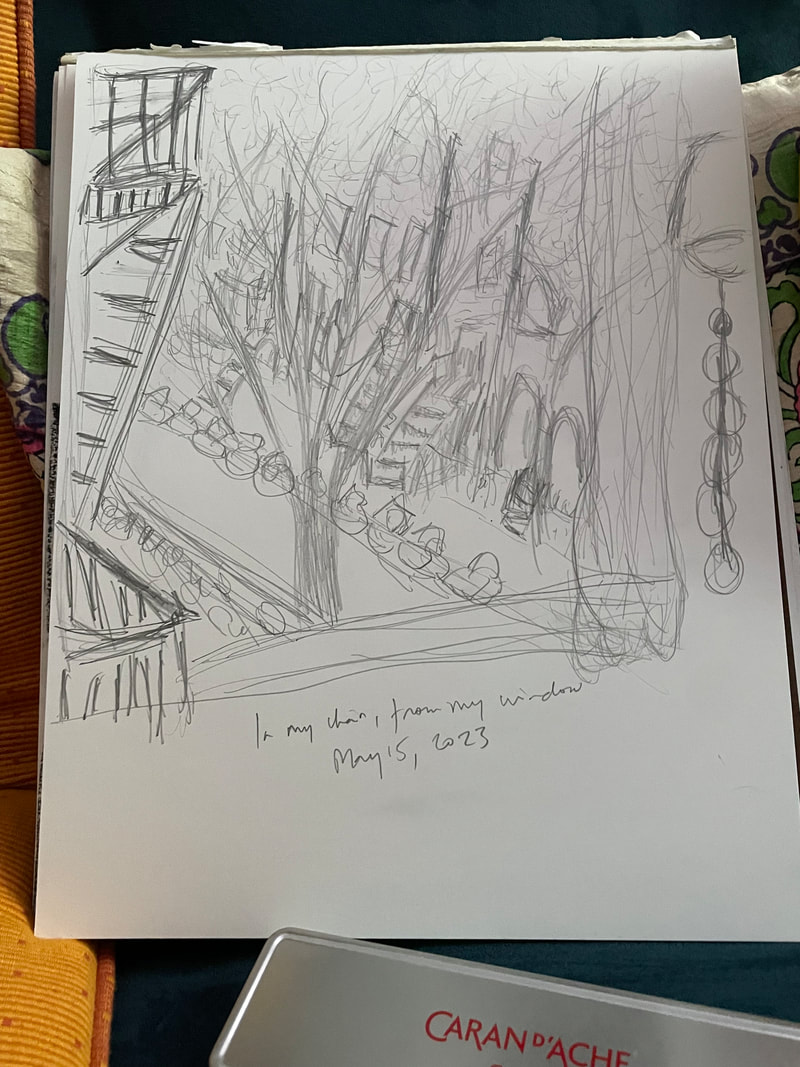

Composition: writing like a visual artist Composition Routine Joy When I start a new piece, I throw myself into writing, a sensual, wordy mix of hand movements — fingers tapping, or moving pen — and the heady intoxication of words, like a visual artist drawing and cutting lines through space, always falling short of the depth of each perspective, each frame, and the grades of light and shadow. I don’t know what is going to happen. I clutch an idea, something between a prop and destination. I propel myself beyond foolishness and prophecy. I, unfailingly human and impostor, am representing life, the world, something like that. The words themselves have histories. Composition, put together. Impostor, put upon. Grade, measure, step. If I stick with this, I’ll lose myself, probably you as well. Where is the idea? Seeded in two layers of ordinary life: routine joy, and the tree outside my window, which means the window, the tree, the street bounded by humped cars and brownstones, shadowed stairs and arches, and my eyes catching the light, filling the continuity of that farthest wall through the opacity of branches. My sketch captures only lines and the barest wispy movement of leaves. I started the sketch because I wanted to do some fresh writing again, after months of revision and reading. Not my fourth work yet, there’s more revision to do. Just a short piece, a blog post. On what? Nothing in particular pushed to be thought, to be written. My thoughts are bucketed, moving forward in orderly ways. Those gentle buckets shepherd my unruly feelings as well, expand to give them space, and hold them. After many years of change, my life has fallen back into a routine in which I am loved and loving, some people honor words I utter in writing or in direct relationship, and my coffee is good. There is a routine joy in my life. I laugh more easily. In the gaps between working and loving, listening and caring, I step out with an easy frivolity. It’s a happy feeling. But wait, how much can I write about that? It doesn’t hold the meaning of life — whatever that is — and I know its evanescence, I know some — many! — of the shadows below it, it being that routine joy. Presupposing the limitations of that routine joy, I couldn’t start that new writing and so, itching and driven to do something, I sketched the tree in my window, which, as I have already said, is not just the tree. I was sketching again after an even longer break than writing, about a year and a half. As with the blankness that met my fresh writing intention, there was no particular shape or emotion that revealed the subject-object of the sketch. But I love looking out at my street from that window, and that tree is a mirror; also beautiful, with some dead branches, and changes with the seasons. So the tree, of course! I anchored the sketch with the fire-escape and now one might say the sketch is of the fire-escape, anchoring as it does everything that’s also in that gaze. This was a very frustrating sketch. I have no illusions about myself as a visual artist — I’m just a scribbler — but I couldn’t capture the range of perspectives that my eye does, that I can sense! Does the photograph capture more than the sketch? It has more shadows. Or does the sketch, with the shiftiness of my eyes and the frustration of my hand, capture more than the photograph? As representations they are both my impositions, my sorry expressions of what I sense and feel and think. But, sorry or not, they are also expressions of my life reaching out and touching life on my street. Spring is so beautiful. This same street has lived garbage, winter, storms, covid, solitude (both still and staggering), collectors of recyclables — the hardest working!! — and now, with me, routine joy, from me, but not just me, not just joy, but, yes, also joy. As I cannot raise despair to flat, so I will not reduce joy to flat. I am alive with all of it. Dharma and Buddha nature, or layering is a form of propagation

A few weeks ago two different thought clouds clapped against my mind like disparate cymbals, but with no violent residue, no headache. The sounds — the force of each — struck moment after moment of my mind, each confused with the other, and resounded, ringing with joyfully learned, naturally moving polyrhythms. There you have it, the word “nature,” both the ground from which roots draw the substance of life and the material of the roots and tips, indeed the air of respiration. Layering is a form of propagation, Elaine Ng, an artist and my friend taught me. When I told her about how the last months have been, for me, a popping out of a multi-year experience of bewilderment as one life structure after the other changed, some by my choice, some fated by the course of my own and others’ lives, some changes woeful, some joyful, the whole bewildering, I concluded that now, after popping out, I feel like a grown and aged baby. A rooted seedling, she responded. A perfect metaphor I exclaimed, a rooted seedling! I went on to further describe the wending of my aged babyhood. She listened and listened; I’m long-winded. And then she said, I’m revising my metaphor. I looked skeptical. What could be better? And she conjured up and recited a truer metaphor after all. Layering, she said, layering, which is a form of propagation. If you’ve read or heard me speak about my first novel, you’ll know that layering is the ground I walk on, the air I live in, even — to hold no exuberant excess back — the thermoclines I ripple through when diving. (Hmmm, there are no thermoclines in my first novel.) Hunh, I responded curiously and unusually pithily. I said seedling, she said, but you’re a grown plant. A grown plant can get knocked over by something outside itself. It may fall over, be driven to touch the ground. In ideal circumstances, the fallen plant will shoot roots into the ground on which it lies. It’ll draw from the remaining strength of the original plant to grow again with new roots, its tip growing up into new life. After a while this new growth is independently strong. The original plant does not necessarily die, but if you cut it off, the new plant will still live and grow. I’d never known anything like this, so I looked at her with wonder. This is layering, she said, a form of propagation. Really? There are real plants that do this? Is this like the banyan tree? No, I’m not talking about aerial roots like the banyan has, nor about the bowed rooting that is part of the normal growth practice of forsythia and cane plants (mind you, through all of this I was gaping in my mind, if not on my face, an amazed and delighted gaping). I believe, she said, offering the caveat that she is no expert botanist, that “layering” implies that something external forces the plant to the ground. Do you have an example, I asked, a plant I may know? Time, she said. No, she did not say time. Thyme, she said. Thyme! Of course. So what does all of this have to do with dharma or Buddha nature, beyond all of these sharing a space in my mind, a time in my life, that morning of October 21, 2022? Well, let’s start with dharma. I am not referring to what is commonly understood as dharma in Buddhist traditions, but rather a Hindu notion of dharma that I learned as a child and youth. As I absorbed various inflections of “dharma” through stories and philosophical writings, I came to understand it as who one is, living who one is. Your dharma is directly related to who you are, your dharma is to live who you are. This notion is complicated. It’s been pressed into justifying socio-economic stratification in ways which have spilled into brazen constraint and cruelty, as when Hindus have insisted on some version of: you must, you can only, live your caste or lack thereof — your high status, your low status, that’s who you are, that’s your dharma. However, in the stories and philosophical writings I encountered, there are enough examples in which “dharma” is not bound to structural position. I found enough boundary-crossing that I came away with a notion that can expansively hold a complex mess of being human. But then one could ask: do you mean that serial murderers can justify their practice of killing people by saying they are living their dharma? That would suggest a notion so immoral that it has no meaning beyond willful, contingent idiosyncrasy. Technically, yes, a serial murderer could say that. But my dharma, and many of yours too I suspect, includes stopping harm to others, especially what looks like wanton murder, and so we’ll try to find ways or support ways — investigative, judicial, preventive, etc. — to do that. From this perspective community norms and statecraft may be viewed as the collective expression of recurrent and overlapping elements of individual dharmas, including dharma elements related to loving, sharing, seeking well-being, seeking domination, seeking overweening survival-to-immortality, destroying an obstacle, propagation, growth. But this kind of efflorescing, even rampant, dharma sounds very different from Buddhist notions of dharma which modestly propose a way to live with no, or at least less, suffering by giving up the delusion that if you get what you desire you will not suffer. The Buddhist way is taught in a combination of practice and precepts that often enough sound and feel prescriptive. Buddhist understandings of dharma — that I draw from my sporadic chunks of practice with Zen sanghas, and my mostly autodidactic reading and home practice of Zen and Tibetan Buddhist traditions — have both attracted and puzzled me. A mystical, Taoist aspect deeply appeals to me because it seems to hold the length and width of what is knowable and unknowable, but then when I read “when love and hate are both absent everything becomes clear and undisguised,” (Chien-chin Seng-ts’an, Third Zen Patriarch), I make that concise sound again — Hunh? Well, I’m not going to stop loving, so I guess I must focus on not hating, no dualism, so all love, all-all. And from there I’m back to trying to be good, to only love. Efforts to only love mean constantly denying or suppressing parts of myself, or feeling guilty, trying to be better. Not that trying to be better is bad, but denial and suppression invariably come back to bite me. The Buddhist teachers I read foresee that happening and tell me that’s no good either. Ok then, feel nothing, think nothing. That’s not happenin’! Then, on that same day as layering opened up and when I was feeling a nagging conflict of “shoulds” — including the insidious should not-should — around a personal dilemma, I read some pages of Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind for the nth time: “When there is no gaining idea in what you do, then you do something. … It is just you, yourself, nothing special.” Bingo! It’s my Hindu notion of dharma! Buddha nature is living who you are. Nothing special. So maybe greedy, conflicted, unhappy is who I am, so nothing further to be done, you might say to me. Maybe, I would respond. I can’t tell you who you are. I could tell you what I experience but that may or may not be interesting or helpful to you. But if you want to feel differently, be more comfortable in yourself, I do find the Buddhist path to the root of your suffering a helpful practice and exploration. Importantly it’s a living that has no end apart from itself; it both has a goal and no goal. From this perspective, fulfillment is not a levitating cushion of certainty. I’ve found the path laid out by Chogyam Trungpa, particularly in his teachings in The Truth of Suffering, helpful. His detailed description of the path of the Hinayana way to liberation from suffering starts annoyingly prescriptive and ends with illumination of a potential passage to clarity about who one is. Parenthetically, Trungpa’s teachings seem to contrast oddly with accounts of his un-Buddhist sounding lifestyle that apparently included womanizing and alcoholism. These may seem logically inconsistent, even hypocritical, but they are not inconsistent in the body, mind, and emotions of a human. This way of looking at it is not about justification, it’s about seeing all the parts.* Nothing special. Trungpa’s teachings, along with the backdrop of his life, are dramatically different from Suzuki’s austere expressions of his Mahayana way, but they converge for me on an understanding of life, of Buddha nature. This Buddha nature is nothing special; we all have it, we can all uncover it, and it’s not all one thing. I realize that many committed Buddhists may find what I’ve written here inaccurate or misleading. To them and to you, my dear reader, I say: find your way. This is where I am on my meandering way — sometimes dancing along, sometimes staggering with too much, sometimes taking the long way deliberately, sometimes levitating on that cushion of delusional certainty, sometimes the cushion collapses and I fall to the ground, and then LAYERING! Among the recent life changes that bewildered me, my mother passed away from pancreatic cancer. She was my remaining parent and caring for her in her last months turned my experience of life from living and death to dying and alive. Caring for her I became corporeally aware of impermanence, of how life falls away from body and consciousness even as we live as we are now. So here I am: new growth, energetically grounded in impermanence, uncertainty, and incompleteness. Alive. I can only live who I am, die who I am. Nothing special. * Is it too much, too extravagant, pushing limits too far to suggest that you read Rita Dove’s brilliant, lovely poem “The Regency Fete” in this context? AND I struggle with how this notion of dharma or Buddha nature can become a refuge, a delusion in itself, whether on the cushion or debauched like the Prince Regent or colluding, by commission or omission, in the collective injustices of one set of people upon another. Where is dharma there? Whose dharma? If I have the answer in one dimension, I don’t in another. Uncertainty, incompleteness, imperfection, nothing special. More meandering through dharma, vegetation, changing light, inconclusive living A couple of weeks after the above piece was first drafted, I looked out of my window and gazed at a tree — mostly yellow, some green still, a few bare twigs — glowing in the morning sunlight, and mused: if I am the tree, I can’t be the sun. But I can enjoy that light, let it warm me, feed me, enrich my living. And I can glow and be beautiful just as I am, making the beauty of my spread and my colors, just as I am. And perhaps someone like me will look at me and see that spread, those colors, my glow. I may not know it, I may never know that Meenakshi watched my leaves grow yellow and fall in yellow showers and loved me and felt her life enriched by me. It’s just the way I am, I live, until I don’t. These sentiments, projected onto and drawn from the tree and the sunlight, became conscious as I decided to continue reading Andrey Tarkovsky’s lovely Sculpting in Time. But first I dipped back into Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind and found myself reading what seemed to me exactly the description of my vegetative life that morning (though perhaps not quite obvious in this telling): “When you know everything, you are like a dark sky. Sometimes a flashing will come through the dark sky. After it passes, you forget about it, and there is nothing left but the dark sky. The sky is never surprised when all of a sudden a thunderbolt breaks through. And when the lightning does flash, a wonderful sight may be seen. When we have emptiness we are always prepared for watching the flashing…. If you want to appreciate something fully, you should forget yourself. You should accept it like lightning flashing in the utter darkness of the sky.” [Meenakshi’s added note: forget the should as well.] Of course that vegetative sharing of life with the tree came in the morning, in a time of glory and reflection. But then, that same evening, as I was lower, duller, I looked at that same tree that now, like me, felt night fall heavily. Another dog had pooped, another man had peed. A paper cup and a plastic bag lay in the speckled mud of the tree bed. If I were the tree I’d be wondering: where will my seeds go? (This tree has lovely large, dark clumps of seed pods.) Why do I even bother morning after morning, night after night? So this is living, it’s not all glory and reflection. I’m also reading Moby Dick. Melville names submission and endurance as womanly virtues, in one of his rare references to the female of a species; most such references offer soft contrasts to the looming, flailing masculinity of the more obviously active characters, indeed of the exploration itself. So, does the tree submit and endure? Is that its action and heroism? Inconclusion I listen to music as a non-musician, naively. Every listening, even a repeat, or much-repeated, listening is naive. Naïveté in listening is the foundation for the ecstatic luxury of body and sound when I am listening to music. Movement may or may not enter the act; body in stillness is still body, still hearing and sensing the reverberation that is sound.

I listen to a lot of music, infinitely different kinds. In the universes of music I have encountered — with ever greater density rushing past me, mushrooming, my body relentlessly naive — I have found only occasional spots that have stopped me short, but no, I will skirt around that path, it’s not interesting. Sound — the music I stay with, but sometimes even and consciously ordinary sound — may be just strung or dropped notes without words. Or: that sound that catches and holds me, that I behold so to speak, may be words that give histories, expressive consciousness of a sort, to the notes that run through them. In music, I listen to words as sound first, and as words after. Often I barely listen to the words as words at all. This is certainly true about words in languages I don’t know, but often this is true about words in languages I know as well. When I listen to the words, often I hear just a repetition or a phrase, sometimes I hear the wrong words, meaning the words I hear or place in that music are not the words that are formally part of that composition. When I listen to the words, however I hear them, I attach conscious meaning to that phrase of music, to that sound composition as a whole. Sometimes that meaning is fragmentary and surrounded by the corporeal and unconscious sensation of music on and in the body, and sometimes it dominates the composition. Whether scattered, ethereal, or dominant, the meaning permeates the composition, not in some completed or static way, but in a dynamic, evolving, and sometimes dying way. Returning from my digression into meaning, in the primary experience of listening naively, music as sound and body is meaningless. This post was catalyzed by listening to the music of Son Lux for the first time. I haven’t dared write about music before this because, well, I’m naive. But some days ago, I listened to Son Lux for the first time. Initially this was an unconscious listening to the background sound of the tumbling pictures and disorderly words of the film Everything Everywhere All at Once. The film is such an eye-popping feast of increasingly riotous movement and meaning that I didn’t notice the music until the credits. That’s a compliment to the synchronicity of the music with the psychedelic movements and meanings that lurch with the characters and their stories, between bills to pay, receipts to recover, hurtling stereotypes, a stunning range of emotional content, and much more. I only noticed the music, noticed the music as composition in its own right at the end when the score continued through the credits. Aha, this is interesting, I thought. I looked for and listened again to the most obvious track, the song This Is A Life, then bought and downloaded it. After listening to that song a couple more times, I got more curious. Who or what was this Son Lux? So I listened to the full score and loved it. I bought and downloaded all of the two hours. My first few listenings of the whole two hours in one sitting were gloriously naive listenings. There are some words associated with this soundtrack: a few songs with English words; one song with Chinese words; the titles of the songs; and the name of the group that composed this soundtrack using original and sampled music — Son Lux. When I first saw the name Son Lux, I assimilated the word “Son” with its homonym, “son” meaning male progeny. Of course, it’s an electronic boy group. Then as I listened to the full score the first time, the second time, “Son” became sound, and lux became the first syllable of luxury, sensuous excess. And that led to this first written reflection on music — indeed sound — as I hear it. Madre and desmadre

I very recently became aware of a Spanish word desmadre, first spoken more generally in my presence and then directly to me by a group of magnificent women in the centre of San Diego. I was told desmadre means ruckus. The way I heard them use the word, it sounded like John Lewis’s “good trouble.” I thought it was two words. Of mothers? No, no, I was told, one word, meaning ruckus. The word intrigued me. Does it have something to do with madre? Well, of course it has something to do with madre, I found. It comes from a root of separation from the mother. Disintegration. Chaos. And now good trouble. In my three works of fiction, all the main characters are women: two wandering mothers, one grandmother, many daughters. My first and third work are about separation from the mother, in one case chosen by the mother, in the other not chosen by the mother. I wanted to close these books, close the stories, go from heimlich to unheimlich to heimlich -- the formula for a good novel I was glibly instructed by a literary agent with unliterary tastes — but the characters are broken are broken, whole only in the luminescence of the world in which they live, loved and loving. Earlier this year I presented the artwork edition of my first novel, Night Heron, in Berlin. My daughter introduced me, moderated the presentation and asked me how I came to write this novel about a visual artist who leaves her son for no very good reason, neither heroic ambition nor poor traumatic past. For the first time in all my stumbling, convoluted speaking about this novel, I spoke about the motivating ambition for this story. It was simple and too ambitiously silly to be spoken of before this, but there in Berlin, speaking to my daughter and a group of mostly artists and writers, I said I wanted to create a female Stephen Dedalus, as in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which I had loved as a young woman. I wanted a woman to step out as vividly: the language, yes, but also that stepping out. I found no Dedalus. There was no easy Dedalus, no female derivative who felt remotely real or interesting. My own life at the time — a mother of young children — pushed me to the not-Dedalus figure of a mother of a young son, and then she leaves her son, which is experienced as desmadre by all readers, disturbingly and uncomfortably so for most, satisfyingly provocative in a melancholy way for some. Art and writing has often propelled or reflected desmadre, traditionally in most parts of the world in the voices and through the agonies of men, often men with, or aligned with, more power (though they could and often did write about men of less power and even women). In the last couple of centuries that has changed. This change has become more rapid in the last sixty years or so as women and traditionally less powerful men — less powerful at least in the context of our long modern era of military gunpowder, industrialization, colonization, and rampant capitalism — have explored what it means to articulate main characters from their own experience of work and living in crowded interior and exterior worlds. Which brings me to an early stimulus for this blog post. A few days ago, biographyof.red, an extraordinarily delightful Instagram account that evidently springs from Anne Carson’s work and posts mostly poetry, posted an excerpt from Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. The excerpt, in turn, quotes Henri Bachelin on the conjuring of myth - involving “tragic cataclysms” of the past, and ends of times — around winter hearths. Evidently this conjuring comes from men, most definitely not old women who tell “fairytales.” Bachelard’s and Bachelin’s lovely words inscribe the space in which old masculinist myths can loom. Their words projected to me a willfully blind desire for understanding that penetrates “the end,” that grandly foresees its own tragic failure. I refused this space and asked myself, what larger space do I make, what poetics if life is the hurling of oneself — whether slowly, grandly, or awkwardly — against the hard transparency of end? What poetics, what space for people living splintered lives — loving, working, laughing, living — and expiring despite themselves, where narratives of yawning pasts and distant ends are often unheeded? Yes, yes, I know, Shakespeare, Dickens, the novel. And, yes, how does this relate to madre and desmadre, apart from the obvious gender stuff. Well, yes, the obvious gender stuff is key. Madre, a trope for connection, with all its connotation of home, gathering, shared food, shared corporeality, cooking, fire, transformation, sometimes even hearth. Complaints, shush, small tales, snoring, reaching into “forces and signs” by women and men. Desmadre, inside and outside. Inside and outside bodies, inside and outside that gathering at the hearth, inside and outside the home, heimlich always roughly pixilated, parts spinning into unheimlich, unheimlich pressed into new forms of homeliness by personal and collective intimacies. From trope to subject, madre to desmadre, women and the historically less powerful are saying we will occupy this hearth, we will make the space under crossing highways a hearth, we will make it a space for life, for gathering, for drought-resistant plants, for art that exclaims “we are here!”, and here encompasses the beauty and pain of our pasts, the struggles and dancing of our present, and our shared future of children, life, and death, all of that! I didn’t know how this blog post would spin out. It is still spinning within, tilting into aliveness, spilling into uncertainty. Madre and desmadre are mythical figures of worlds that have long been binary-gendered. As binary gender dissolves into two figures in a much larger flow, or if gestation becomes incubation in genderless machinery and separation becomes connection to a human, will madre — traditionally female, one of a binary, bloody and corporeal — change? I don’t know. The best I can do for now is to observe that the binary was always only a device, a tool for organizing rhetoric and meaning. The non-binary has always been available, residing in both vast madre and desmadre. Reflecting on the mothers in my fiction and the space-making event alluded to above, madre also seems to connote separation and desmadre also connotes connection, gathering. For the last four months, I have been in Chennai, living with my brother and his family, helping take care of my mother who has terminal cancer. This has been a new life for me in many ways: far from my home in West Harlem; reestablishing and deepening bonds of affection with my brother and his family; inverting more fully, with affection and irritation on both sides, my child-parent relationship with my mother; and touching that line between living and dying that is always present in every one of our lives — ‘living is dying’ is a startling truism — though mostly we remain unaware of this illusory line, and when we are forced to face it we tend to fear it, or pacify it by placing it as a central mystery in spiritual or natural cycles.